The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

Rescatan a Elvira

Domingo 12 de Julio de 2015 aCCIÓN EXPRESO 5C A LFONSO ARAUJO BOJÓRQUEZ LOS RED STOCKINGS DE CINCINNATI l Club Cincinnati se estableció el 23 de junio de de acuerdo a aquella época, no Brooklyn y cuando el único am- vino la reacción de los Atlantics, 1866, en un despacho de abogados, en el que elabo- había guantes, el pitcher lanzaba payer, de nombre Charles Mills, que en forma sensacional hicie- raron los estatutos y designación de funcionarios, por debajo del brazo, la distancia cantó el pleybol, había gente por ron tres, para salir con el triunfo E desde donde lanzaba, era de solo todos lados y fácilmente rebasa- 8-7. Los gritos de la multitud se donde eligieron como presidente y lo convencieron de que formara 50 pies, la pelota un poco más ban los 12 mil afi cionados. Los podían escuchar por cuadras a a Alfred T. Gosharn. u n equ ipo profesion a l , busc a ndo chica que la actual y el bat era pitchers anunciados fueron Asa la redonda, escribió el corres- Después de jugar cuatro par- jugadores de otras ciudades, que cuadrado. Brainard, que había ganado to- ponsal del New York Sun. Los tidos en ese verano, se unieron se distinguieran en jugar buen Empezaron ganando con dos los juegos de Cincinnati y se jugadores de Cincinnati abor- en 1867 a la NABBP (National beisbol. Por lo pronto en 1868 mucha facilidad a equipos lo- enfrentaría a otro gran lanzador, daron rápidamente su ómnibus Association of Base Ball Players) llevaron a cabo 16 partidos per- cales y pronto llegó su fama a George Zettlein, que era un buen y dejaron el recinto, molestos e hicieron el acuerdo para jugar diendo solo ante los Nationals de otras ciudades, que los invita- bateador. -

Boston Guide

Ü >ÌÜ >ÌÊ ÌÌÊ ``Ê UUÊ Ü iÀiÜ iÀ iÊ ÌÌÊ }}Ê UUÊ Ü >ÌÜ >ÌÊ ÌÌÊ Ãii September 7–20, 2009 INSIDERSINSIDERS’ GUIDEto BOSTON INCLUDING: -} ÌÃii} / i ÃÌ ÃÌ >` Ì i 9Õ ½Ì i} LÀ ` Àii` /À> Ü Õ`ià E >«Ã NEW WEB bostonguide.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! Johanna Baruch G:8:EI>DC L>I= I=: 6GI>HI H:E EB 6GI :M=>7>I H:E ID D8I oyster perpetual gmt-master ii CJB>CDJH D>A DC E6C:A 60" M 44" European Fine Arts Furnishings, Murano Glass, Sculptures, Paintings, Leather, Chess Sets, Capodimonte Porcelain OFFICIALROLEXJEWELER ROLEX OYSTER PERPETUAL AND GMT-MASTER II ARE TRADEMARKS. H:K:CIN C>C: C:L7JGN HIG::I s 7DHIDC B6HH68=JH:IIH telephone s LLL <6AA:G>6;ADG:CI>6 8DB 6 91, " , 9 "/" */ *** -/ 1 * ,* /" 9 *" ,"9 ,/ , **"/ 8 - *1- 1 / 1 E , , , - "/" contents COVER STORY 10 The Boston You Don’t Know Everything you didn’t know you wanted to know about the Hub DEPARTMENTS 8 hubbub 54 around the hub Cambridge Carnival 54 CURRENT EVENTS 62 ON EXHIBIT 18 calendar of events 66 SHOPPING 73 NIGHTLIFE 20 exploring boston 76 DINING 20 SIGHTSEEING 31 FREEDOM TRAIL 33 NEIGHBORHOODS 47 MAPS WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE: The seemingly mis- named Harvard Bridge spans the ``ÊÌ iÊ*iÀviVÌÊ >` Ì i *iÀviVÌ >` Charles River, connecting the Back Bay with the campus of the ÜÜÜ° Àii°V Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Refer to story, page 10. PHOTOBY ,58,58"/.$'2%%. "/.$ '2%%. C HRISTOPHER W EIGL *%7%,29 7!4#(%3 ')&43 s 3).#% on the cover: {£È ÞÃÌ -ÌÀiiÌ "-/" ȣǮ ÓÈÈ°{Ç{Ç A statue of famed patriot Paul Revere stands along the * ,* // 1 , ,/ , 8 - *1- 1 / ,,9 "/, >V , , - "/" **"/ >Þ LiÌÜii À}Ì >` iÀiiÞ -ÌÀiiÌ® Freedom Trail near the Old North Church in the North End. -

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

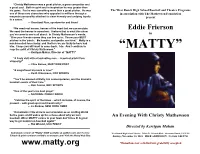

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Residents Struggling to Carve out a New Life Amid Michael's Devastation

CAUTION URGED FOR INSURANCE CLAIMS LOCAL | A3 PANAMA CITY SPORTS | B1 BUCKS ARE BACK Bozeman carries on, will host South Walton Tuesday, October 23, 2018 www.newsherald.com @The_News_Herald facebook.com/panamacitynewsherald 75¢ Radio crucial Step by step after Cat 4 storm When newer technologies failed, radio worked following Hurricane Michael’s devastation By Ryan McKinnon GateHouse Media Florida PANAMA CITY — In the hours following one of the biggest news events in Bay County history, residents had little to no access to news. Hurricane Michael’s 155 mile-per-hour winds had toppled power lines, television satel- lites, radio antennas and crushed newspaper offices. Cellphones were useless across much of the county with spotty- at-best service and no access to internet. It was radio static across the radio dial, Peggy Sue Singleton salvages from the ruins of her barbershop a sign that used to show her prices. Only a few words are now legible: “This is the happy place.” [KEVIN BEGOS/THE WASHINGTON POST] See RADIO, A2 Residents struggling to carve out a new life amid Michael’s devastation By Frances Stead strewn across the parking lot Hurricane Michael was the reliable cellphone service and Sellers, Kevin Begos as if bludgeoned by a wreck- wrecker of this happy place. access to the internet. and Katie Zezima ing ball, her parlor a haphazard It hit here more than a week This city of 36,000 long has The Washington Post heap of construction innards: ago, with 155-mph winds that been a gateway to the Gulf, LOCAL & STATE splintered wood, smashed ripped and twisted a wide a white-beach playground A3 PANAMA CITY — Business windows, wire. -

Impartial Arbiter, New Hall of Famer O'day Was Slanted to Chicago in Personal Life

Impartial arbiter, new Hall of Famer O’Day was slanted to Chicago in personal life By George Castle, CBM historian Monday, Dec. 17 For a man who wore an impenetrable mask of reserve behind his umpire’s headgear, Hank O’Day sure wore his heart on his sleeve when it came to his native Chicago. O’Day was serious he only allowed his few close friends to call him “Hank.” He was “Henry” to most others in his baseball trav- els as one of the greatest arbiters ever. But in a Chicago he never left as home, he could be himself. Born July 8, 1862 in Chicago as one of six children of deaf parents, O’Day always came back home and lived out his life in the Sec- ond City. He died July 2, 1935 in Chicago, and was buried in the lakefront Calvary Cemetery, just beyond the north city limits in Evanston. In between, he first played Hank O'Day in civilian clothes baseball competitively on the city’s sandlots as Cubs manager in 1914. with none other than Charles Comiskey, the founding owner of the White Sox. And in taking one of a pair of season-long breaks to manage a big-league team amid his three-decade umpiring career, O’Day was Cubs manager in 1914, two years after he piloted the Cincinnati Reds for one year. Through all of that, his greatest connection to his hometown was one of the most fa- mous calls in baseball history – the “out” ruling at second base on New York Giants rookie Fred Merkle in a play that led to the last Cubs World Series title in 1908. -

A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions

Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions Joseph J. McMahon Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph J. McMahon Jr., A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions, 2 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 213 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McMahon: A History and Analysis of Baseball's Three Antitrust Exemptions A HISTORY AND ANALYSIS OF BASEBALL'S THREE ANTITRUST EXEMPTIONS JOSEPH J. MCMAHON, JR.* AND JOHN P. RossI** I. INTRODUCTION What is professional baseball? It is difficult to answer this ques- tion without using a value-laden term which, in effect, tells us more about the speaker than about the subject. Professional baseball may be described as a "sport,"' our "national pastime,"2 or a "busi- ness."3 Use of these descriptors reveals the speaker's judgment as to the relative importance of professional baseball to American soci- ety. Indeed, all of the aforementioned terms are partially accurate descriptors of professional baseball. When a Scranton/Wilkes- Barre Red Barons fan is at Lackawanna County Stadium 4 ap- plauding a home run by Gene Schall, 5 the fan is engrossed in the game's details. -

Download in Short, They Represent Hope

Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 64 NO. 4 WINTER 2010 The !"#$%Goes On Its &'($') Changes ENERGY • SPORTS • GOVERNMENT • FAMILY • SCIENCE • ARTS • POLITICS + MORE BEATS ‘to promote and elevate the standards of journalism’ Agnes Wahl Nieman the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation Vol. 64 No. 4 Winter 2010 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University Bob Giles | Publisher Melissa Ludtke | Editor Jan Gardner | Assistant Editor Jonathan Seitz | Editorial Assistant Diane Novetsky | Design Editor Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Editorial in March, June, September and December Telephone: 617-496-6308 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, E-mail Address: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. [email protected] Subscriptions/Business Internet Address: Telephone: 617-496-6299 www.niemanreports.org E-mail Address: [email protected] Copyright 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subscription $25 a year, $40 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $7.50. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Massachusetts and additional entries. Please address all subscription correspondence to POSTMASTER: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 Send address changes to and change of address information to Nieman Reports P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. P.O. Box 4951 ISSN Number 0028-9817 Manchester, NH 03108 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 64 NO. 4 WINTER 2010 4 The Beat Goes On—Its Rhythm Changes The Beat: The Building Block 5 The Capriciousness of Beats | By Kate Galbraith 7 It’s Scary Out There in Reporting Land | By David Cay Johnston 9 The Blog as Beat | By Juanita León 11 A Journalistic Vanishing Act | By Elizabeth Maupin 13 From Newsroom to Nursery—The Beat Goes On | By Diana K. -

She Ifriltoiflc S In

Try ^ w ea th er THE HILLSIDE 'TIMES >nd somewhat warawJ to- For Your Next Order Of Ui tome1TOf ’ . v'> ; , She Ifriltoiflc Sinus PRINTING ^U f^or-660- - HILLSIDE, N, J„ FRIDAY, JULY i m PRICE FIVE CENTS Cougji Vaccine HILLSIDE ELKS AT nHle&fion Authorize Formation Of Industrial FROLIC IN UNION Death Rides Held Success ■’"About twenty-five members of., Hills? Negotiation Board Awaiting Report side Lodg'fe 1591, B. P. Q. Elks, attended Highway For It an informal .outdoor frolic b n the Formation of an official Industrial could, toe a .part' of the, industrial Asso-. Health Physician -Believes grounds: of Union Lodge last night wnets call N orth - Broad Plffitiiiiiag Board for the township was tatidn, "tout, deblared his wiflngness tqt The .occasion wds’: th e birthday-. anni Eg of Rid?way av^tde, W W Of H.S. Site delayed another week, w hen: flo report support' ahy. plan Which would pro- Semm Will Become More versary'of Ohailes 'V^'^Mink, thred Second Time i received by the Township Commit- tecT industfy and bring otlers Jibre, Effective With Time times exalted ruler" of 'the Union group. ^ uhml said th is week in WedheSday night from-the Shows Bayonne Pamphlet other "lodges’ were repre® iits on' the east siae oi CnmnntteB Givte ■School- pidiiiiing its w g a m z a m r wuow- ""'"ECiwara T rm c g i^ ..tfeuenjr 7 leading Elks .of the City Man Succumbs te declared f f l i M i M M Board Power tp Buy a Ing* a meeting Monday with -repr m ent agent for th e Lehigh mlley R ail- sough vaccine in Hillside doning- thS state .