1826 CHESTNUT ST Name of Resource: Aldine Theatre Proposed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 Student HADDBDDH 1948- 1949

P. M. C. 0 Student -HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 Student HADDBDDH 1948- 1949 0 Pennsylvania 5J1ilita'Ly College Cfteste\, Pennsylvania FRESHMAN HANDBOOK 3 PREFACE TO THE STUDENTS The Student Handbook is published for you and is supported by funds provided by the non-athletic activities fee. It was firs~ published in September 1948 as the Fresh man Handbook. This year it is available for all students in the hope that it will be a useful and profitable guide. Its purpose is to anticipate and answer questions you may have, to acquaint you with the history of P.M.C., to apprise you of academic rules and regulations, to point out what is ex pected of you by the faculty and yo~ fel low students, and to urge you to participate in some extra-curricular activity. THE EDITOR. 4 FRESHMAN HANDBOOK ••• • • • II I • I I- ~~-------· ----· FRESHMAN HANDBOOK 6 PRESIDENT HYATT'S MESSAGE TO T"HE MEMBERS OF THE ENTERING CLASS It is my great pleasure, in behalf of the faculty and the student body, to extend t9 you, the members of the new freshman class, both cadets and veteran students, a most cordial welcome to the Pennsylvania Military College. It is only since the last war that P.M.C. has had a civilian student body in addition to its corps of cadets. It has been gratify ing to see these two groups of college stu dents work hand in hand toward a common goal-a stronger and better P.M.C. I am sure that you, too, will cooperate in the same manner. -

List of Tax Reform Good News

List of Tax Reform Good News 1,200 examples of pay raises, charitable donations, special bonuses, 401(k) match hikes, business expansions, benefit increases, and utility rate reductions attributed to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act As of August 17, 2020. Please send any additions to this list to John Kartch at [email protected] This list and all 50 state lists are constantly updated – please access this national list and all 50 state lists at www.atr.org/list A 1A Auto, Inc. (Westford, Massachusetts) -- Bonuses for all full-time employees: Massachusetts based online auto parts retailer 1A Auto announced across the board cash bonuses for all full-time employees. CEO Rick Green says that the decision was based on recent changes to tax policy. In a company meeting Wednesday, Green told employees, "Ultimately the tax savings will be passed to our customers in the form of lower prices, but we want to also share some of the savings with you, our hard-working employees." Jan. 25, 2018 1A Auto, Inc. press release 2nd South Market (Twin Falls, Idaho) -- A food hall is opening because of the TCJA Opportunity Zone program, and is slated to create new jobs: One of the nation’s fastest-growing trends, food halls, is coming to Twin Falls. 2nd South Market, slated to open this summer, will be housed in the historic 1926 downtown Twin Falls building formerly occupied by the Salvation Army. 2ndSouth Market will be the first Opportunity Zone project to open in Idaho and the state’s third Opportunity Zone investment. -

Page 14 Street, Hudson, 715-386-8409 (3/16W)

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 1 10/14/10 7:08 PM ANNOUNCING A NEW DVD TEACHING TOOL Do you sit at a theatre organ confused by the stoprail? Do you know it’s better to leave the 8' Tibia OUT of the left hand? Stumped by how to add more to your intros and endings? John Ferguson and Friends The Art of Playing Theatre Organ Learn about arranging, registration, intros and endings. From the simple basics all the way to the Circle of 5ths. Artist instructors — Allen Organ artists Jonas Nordwall, Lyn Order now and recieve Larsen, Jelani Eddington and special guest Simon Gledhill. a special bonus DVD! Allen artist Walt Strony will produce a special DVD lesson based on YOUR questions and topics! (Strony DVD ships separately in 2011.) Jonas Nordwall Lyn Larsen Jelani Eddington Simon Gledhill Recorded at Octave Hall at the Allen Organ headquarters in Macungie, Pennsylvania on the 4-manual STR-4 theatre organ and the 3-manual LL324Q theatre organ. More than 5-1/2 hours of valuable information — a value of over $300. These are lessons you can play over and over again to enhance your ability to play the theatre organ. It’s just like having these five great artists teaching right in your living room! Four-DVD package plus a bonus DVD from five of the world’s greatest players! Yours for just $149 plus $7 shipping. Order now using the insert or Marketplace order form in this issue. Order by December 7th to receive in time for Christmas! ATOS NovDec 52-6 H.indd 2 10/14/10 7:08 PM THEATRE ORGAN NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2010 Volume 52 | Number 6 Macy’s Grand Court organ FEATURES DEPARTMENTS My First Convention: 4 Vox Humana Trevor Dodd 12 4 Ciphers Amateur Theatre 13 Organist Winner 5 President’s Message ATOS Summer 6 Directors’ Corner Youth Camp 14 7 Vox Pops London’s Musical 8 News & Notes Museum On the Cover: The former Lowell 20 Ayars Wurlitzer, now in Greek Hall, 10 Professional Perspectives Macy’s Center City, Philadelphia. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Fraternalism — an Indelible Mark" Ate Will Sponsor the Leadership Con Several Staff Openings for by Mario A

Basketball At LambdaChi Alpha's Sayre Jr. High Winter Warm-Up 09EXEL INSTITUTE Saturday, Jan. 14 Tomorrow 3:30 OF TECHNOLOGY Sylvania Hotel phiudeiphia , p a . VOLUME XXXVIII JANUARY 13. 1961 NUMBER 1 Lambda Chi Alpha Presents Lissy Voted All-American/ "A Night With Playboy" OfOOOnS Win MAC CfO W Il •‘A• * V Niuhtvitriit with Playboy"PUivbov” will be nronriatelvpropriately decorateddproratpri in typicaltvnirnl the theme of this year’s Winter Playl)oy good taste. Lighting will single season in 19.tS until it was Warm-Up. The brothers of Lam b be soft and mellow— just right for broken this past year. This past da rhi Alplia fraternity have tradi that special girl you call your season lie led the Dragons to their tionally held the first all-school Playmate. Clos3 to a dozen ex second MAC crown in the last three (lance and have again this year clusive Playboy prizes will be dis years. Lissy had 15 goals and 1<» planned a seemingly outstanding tributed at the dance, such as “The assets which placed him on the MAC affair. Many members of Drexel's Best of Playboy” (joker), and the First Division Team. “The Best of Playboy” (cartoons), freshman class are expected to at The outstanding game of the sea- sterling silver Playmate earrings, tend this opening affair for the scn. which put us into the MAC bracelets, and necklaces. Winter Hushing Season. championships, was with Johns Hop This is the first year that the A1 Raymond and his orchestra kins of Baltimore. A double over Lambda ('hi’s have built their will provide music for the evening time which resulted in Drexel’s win (lance around a central theme. -

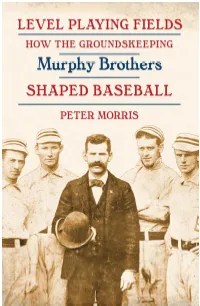

Level Playing Fields

Level Playing Fields LEVEL PLAYING FIELDS HOW THE GROUNDSKEEPING Murphy Brothers SHAPED BASEBALL PETER MORRIS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN & LONDON © 2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska ¶ All rights reserved ¶ Manufactured in the United States of America ¶ ¶ Library of Congress Cata- loging-in-Publication Data ¶ Li- brary of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data ¶ Morris, Peter, 1962– ¶ Level playing fields: how the groundskeeping Murphy brothers shaped baseball / Peter Morris. ¶ p. cm. ¶ Includes bibliographical references and index. ¶ isbn-13: 978-0-8032-1110-0 (cloth: alk. pa- per) ¶ isbn-10: 0-8032-1110-4 (cloth: alk. paper) ¶ 1. Baseball fields— History. 2. Baseball—History. 3. Baseball fields—United States— Maintenance and repair. 4. Baseball fields—Design and construction. I. Title. ¶ gv879.5.m67 2007 796.357Ј06Ј873—dc22 2006025561 Set in Minion and Tanglewood Tales by Bob Reitz. Designed by R. W. Boeche. To my sisters Corinne and Joy and my brother Douglas Contents List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgments ix Introduction The Dirt beneath the Fingernails xi 1. Invisible Men 1 2. The Pursuit of Pleasures under Diffi culties 15 3. Inside Baseball 33 4. Who’ll Stop the Rain? 48 5. A Diamond Situated in a River Bottom 60 6. Tom Murphy’s Crime 64 7. Return to Exposition Park 71 8. No Suitable Ground on the Island 77 9. John Murphy of the Polo Grounds 89 10. Marlin Springs 101 11. The Later Years 107 12. The Murphys’ Legacy 110 Epilogue 123 Afterword: Cold Cases 141 Notes 153 Selected Bibliography 171 Index 179 Illustrations following page 88 1. -

Vol. 29, No. 6 2007

Vol. 29, No. 6 2007 PFRA Committees 2 Football’s Best Pennant Races 5 Bob Gain 11 Baseball & Football Close Relationship 12 Right Place – Wrong Time 18 Overtime Opinion 19 Forward Pass Rules 21 Classifieds 24 THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 29, No. 6 (2007) 2 Class of 2003: Class of 2004: Gino Cappelletti Gene Brito Carl Eller* John Brodie PFRA Pat Fischer Jack Butler Benny Friedman* Chris Hanburger Gene Hickerson* Bob Hayes COMMITTEES Jerry Kramer Billy Howton By Ken Crippen Johnny Robinson Jim Marshall Mac Speedie Al Nesser Mick Tingelhoff Dave Robinson We are happy to report that another committee has Al Wistert Duke Slater been formed since the last update. Gretchen Atwood is heading up the Football, Culture and Social Class of 2005: Class of 2006: Movements Committee. A description of the committee Maxie Baughan Charlie Conerly can be found below. Jim Benton John Hadl Lavie Dilweg Chuck Howley The Western New York Committee is underway with Pat Harder Alex Karras their newest project, detailing the Buffalo Floyd Little Eugene Lipscomb Bisons/Buffalo Bills of the AAFC. Interviews with Tommy Nobis Kyle Rote surviving players and family members of players are Pete Retzlaff Dick Stanfel underway and will continue over the next few months. Tobin Rote Otis Taylor Lou Rymkus Fuzzy Thurston The Hall of Very Good committee reports the following: Del Shofner Deacon Dan Towler In 2002, Bob Carroll began the Hall of Very Good as a Class of 2007: way for PFRA members to honor outstanding players Frankie Albert and coaches who are not in the Pro Football Hall of Roger Brown Fame and who are not likely to ever make it. -

Hey, College Sports. Compromise on Compensation and You Can Have a Legal Monopoly Todd A

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 26 Issue 2 Symposium: The Changing Landscape of Article 10 Collegiate Athletics Hey, College Sports. Compromise on Compensation and You Can Have a Legal Monopoly Todd A. McFall Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Todd A. McFall, Hey, College Sports. Compromise on Compensation and You Can Have a Legal Monopoly, 26 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 459 (2016) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol26/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MCFALL FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 6/14/2016 5:35 PM HEY, COLLEGE SPORTS. COMPROMISE ON COMPENSATION AND YOU CAN HAVE A LEGAL MONOPOLY TODD A. MCFALL* OVERVIEW The fate of the century-old National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has never been as tenuous as it is currently. Court disputes regarding the legality of the organization’s long-standing scholarship-as-compensation model are in full bloom, and the decisions in these disputes, which range from suits like O’Bannon v. NCAA, a dispute that could have a somewhat large impact on NCAA policies,1 to suits like Jenkins v. NCAA,2 which asks the courts to overturn completely the compensation structure offered to scholarship athletes,3 could call for huge changes to the way college sports operate.4 If the courts side with any one of the plaintiffs in these suits, the NCAA and its members will face difficult questions about how to operate in a world with completely shifted legal constraints. -

Program Book

THE 21ST ANNUAL PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 4, 2014 LANDMARKS ANDLEADERS JUNE 4, 2014 Lincoln Hall Union League of Philadelphia LANDMARKS MASTER OF CEREMONIES Emmy-winning journalist ANDLEADERS T D Anchor NBC 10 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 3 SPECIAL RECOGNITION AWARDS 4 JAMES BIDDLE AWARD PUBLIC SERVICE AWARD RHODA AND PERMAR RICHARDS AWARD JOHN ANDREW GALLERY AWARD SPECIAL 50TH ANNIVERSARY RECOGNITION SPECIAL 200TH ANNIVERSARY RECOGNITION IN MEMORIUM 9 GRAND JURY AWARDS 10 AIA PHILADELPHIA AWARDS 18 AIA LANDMARK BUILDING AWARD HENRY J. MAGAZINER EFAIA AWARD SPONSOR RECOGNITION 20 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS STAFF Robert Powers Chair Caroline E. Boyce, CAE GRAND JURY Executive Director John G. Carr AWARDS PANEL Vice Chair Patrick Hauck Director of Neighborhood Karen Arnold Sally Elk Preservation Programs Keystone Grant Preservation Specialist Vice Chair Pennsylvania Historical and Benjamin Leech Barbara J. Kaplan Museum Commission Advocacy Director Secretary Randall Baron Amy E. Ricci Leonidas Addimando Assistant Historic Preservation Officer Special Projects Director Treasurer Philadelphia Historical Commission Harry Schwartz Dorothy Guzzo Advocacy Committee Chair SPECIAL RECOGNITION Executive Director New Jersey Historic Trust Cheryl L. Gaston, Esq. AWARDS Easement Committee Chair ADVISORY COMMITTEE Libbie Hawes Preservation Director DIRECTORS William Adair Cliveden of the National Trust Director Lisa J. Armstrong, AIA, LEED AP, Heritage Program, Robert J. Hotes, AIA, LEED, AP NCARB Pew Center for Arts and Heritage Preservation Co-Committee Chair AIA Philadelphia Suzanna E. Barucco Suzanna Barucco Vincent P. Bowes Principal Janet S. Klein Former Chair sbk + partners, LLC Mary Werner DeNadai, FAIA Pennsylvania Historical and Joanne R. Denworth Mary Werner DeNadai, FAIA Museum Commission Principal Mark A. -

Dave Berry and the Philadelphia Story

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 2, Annual (1980) DAVE BERRY AND THE PHILADELPHIA STORY The Very First N.F.L. When the Steelers won Super Bowl IX, the chroniclers of pro football nearly wet themselves in celebrating Pittsburgh's first National Football League championship. What few of the praisers (and probably none of the praisees) realized was that the 16-6 victory over Minnesota actually gave Pittsburgh its SECOND N.F.L. title. Of course, anyone can be forgiven such an historical gaffe. After all, that first championship came clear back in 1902. And almost no one noticed it then. Or cared. * * * * Throughout the 1890's the best -- and sometimes the only -- professional football teams of consequence was played in southwest Pensylvania: in Pittsburgh and nearby towns like Greensburg and Latrobe. By the turn of the century, Pittsburgh's Homestead team was fully pro and frightfully capable -- so much so that it could find few opponents able to give it any competition. Apathy set in among the fans. The team was too good. The Homesteaders always won, but so easily that they weren't a whole lot of fun to watch. After bad weather compounded the poor attendance in 1901, the great Homestead team folded. The baseball team was great fun to watch. The Pirates were the best in baseball, just like Homestead had been tops in pro football. But the Pirates lost occasionally. There was some doubt when they took the field. Pittsburgh, in 1902, was a baseball town. After a decade of watching losers on the diamond, Smokeville fans had become captivated by the ball and bat game. -

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska Editor Vladimir Kucera Co-Editor Alfred Novacek Venovano ceskym pionyrum Nebrasky, hrdinnym budovatelum americkeho Zapadu, kteri tak podstatne prispeli politickemu, kulturnimu, nabozenskemu, hosopodarskemu, zemedelskemu a socialnimu pokroku tohoto statu Dedicated to the first Czech pioneers who contributed so much to the political, cultural, religious, economical, agricultural and social progress of this state Published for the Bicentennial of the United States of America 1976 Copyright by Vladimir Kucera Alfred Novacek Illustrated by Dixie Nejedly THE GREAT PRAIRIE By Vladimir Kucera The golden disk of the setting sun slowly descends toward the horizon of this boundless expanse, and changes it into thousands of strange, ever changing pictures which cannot be comprehended by the eye nor described by the pen. The Great Prairie burns in the blood-red luster of sunset, which with full intensity, illuminates this unique theatre of nature. Here the wildness of arid desert blends with the smoother view of full green land mixed with raw, sandy stretches and scattered islands of trees tormented by the hot rays of the summer sun and lashed by the blizzards of severe winters. This country is open to the view. Surrounded by a level or slightly undulated plateau, it is a hopelessly infinite panorama of flatness on which are etched shining paths of streams framed by bushes and trees until finally the sight merges with a far away haze suggestive of the ramparts of mountain ranges. The most unforgettable moment on the prairie is the sunset. The rich variety of colors, thoughts and feelings creates memories of daybreak and nightfall on the prairie which will live forever in the mind.