'Kill All the Sorcerers': the Interconnections Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English/Publish/Download/Vrf/Pdf/492.Pdf

GEF/E/C.59/01 November 11, 2020 59th GEF Council December 7-10, 2020 Virtual Meeting Agenda Item 09 EVALUATION OF GEF SUPPORT IN FRAGILE AND CONFLICT-AFFECTED SITUATIONS (Prepared by the Independent Evaluation Office of the GEF) Recommended Council Decision The Council, having reviewed document GEF/E/C.59/01, Evaluation of GEF Support in Fragile and Conflict- Affected Situations, and the Management Response, endorses the following recommendations: 1. The GEF Secretariat should use the project review process to provide feedback to Agencies to identify conflict and fragility-related risks to a proposed project and develop measures to mitigate those risks. 2. To improve conflict-sensitive programming while also providing flexibility to Agencies and projects, the GEF Secretariat could develop guidance for conflict-sensitive programming. 3. To improve conflict-sensitive design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of GEF projects, the GEF Secretariat together with the Agencies should leverage existing platforms for learning, exchange, and technical assistance. 4. The current GEF Environmental and Social Safeguards could be expanded to provide more details so that GEF projects address key conflict-sensitive considerations. 5. The GEF Secretariat could consider revising its policies and procedures so that GEF-supported projects can better adapt to rapid and substantial changes common in fragile and conflict-affected situations ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................... -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

The Legitimacy of Bougainville Secession from Papua New Guinea

https://doi.org/10.26593/sentris.v2i1.4564.59-72 The Legitimacy of Bougainville Secession from Papua New Guinea Muhammad Sandy Ilmi Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Katolik Parahyangan, Indonesia, [email protected] ABSTRACT What started as a movement to demand a distributive justice in mining revenue in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, the conflict turned into the struggle for secession. From 1970’s the demand for secession have been rife and despite early agreement for more autonomy and more mining revenue for the autonomous region, the demand never faded. Under Francis Ona’s Bougainville Revolutionary Army, the movement take a new heights. Bougainville Revolutionary Army took coercive measure to push the government to acknowledge their demands by taking over the mine at Panguna. Papua New Guinean government response was also combative and further exacerbate the issue. Papua New Guinean Defense Force involvement adding the issue of human rights into the discourse. This paper will seek to analyze the normative question surrounding the legitimacy of the right to secession in Bougainville Island. The protracted conflict has halted any form of development in the once the most prosperous province of Papua New Guinea and should Bougainville Island become independent, several challenges will be waiting for Bougainvilleans. Keywords: Bougainville secession; Papua New Guinea conflict; mining injustice; human rights violation ABSTRAK Berawal dari bentuk perlawanan untuk mencapai keadilan dalam pembagian keuntungan dari sektor pertambangan, kemudian berubah menjadi perjuangan untuk memisahkan diri dari Papua Nugini. Sejak 1970an, dukungan untuk pemisahan diri telah mendominasi diskursus politik di Bougainville dan walaupun perjanjian sempat tercapai, keinginan untuk pemisahan diri tidak pernah padam. -

Bibliographie

Bibliographie 1. Das Schrifttum von Wu Leichuan WU LEI-CH’UAN bzw. WU CHEN-CH’UN (WU ZHENCHUN), Pseudonym HUAI XIN Die englischen Titel in Klammern stammen aus den Originalausgaben, wo sich oft (aber nicht immer) ein chinesisches und ein englisches Inhaltsverzeichnis findet. Die Numerierung und Paginierung von SM, ZL und ZLYSM ist in den Originalausgaben, die dem Verfasser nur in Kopien vorlagen, nicht konsistent und oft nur schwer les- bar. Die Beiträge sind chronologisch geordnet. 1918 „Shu xin“ , in: Zhonghua jidujiaohui nianjian 5 (1918), S. 217-221. 1920 „Lizhi yu jidujiao“ (Confucian Rites and Christianity), in: SM 1 (1920), No. 2, S. 1-6. 1920 „Wo duiyu jidujiaohui de ganxiang“ (Problems of the Christian Church in China. A Statement of Religious Experience), in: SM 1 (1920), No. 4, S. 1-4. 1920 „Wo yong hefa du shengjing? Wo weihe du shengjing?“ , in: SM 1 (1920), No. 6, S. 1. 1920 „Wo suo xinyang de Yesu Jidu“ , in: SM 1 (1920), No. 9 und 10. 1921 „What the Chinese Are Thinking about Christianity“. Transl. by T.C. Chao, in: CR (February 1921), S. 97-102. 1923 „Jidujiao jing yu rujiao jing“ , in: SM 3 (1923), No. 6, S. 1- 6. Abgedruckt in Zhang Xiping und Zhuo Xinping (Hrsg.) 1999, S. 459-465. 1923 „Wo geren de zongjiao jingyan“ (My Personal Religious Experience), in: SM 3 (1923), No. 7-8, S. 1-3. 1923 „Lun Zhongguo jidujiaohui de qiantu“ , in: ZL 10. Juni 1923, No. 11. Abgedruckt in Zhang Xiping und Zhuo Xinping (Hrsg.) 1999, S. 333-336. 1923 „Jidutu jiuguo“ , in: ZL 1 (1923), No. -

25 Years of Building Peace

25 YEARS OF BUILDING PEACE Annual Review 2019 Conflict is difficult, complex and political. The world ABOUT urgently needs to find different ways to respond. Conciliation Resources is an international organisation CONCILIATION committed to stopping violent conflict and creating more peaceful societies. We work with people impacted by war RESOURCES and violence, bringing diverse voices together to make change that lasts. We connect the views of people on the ground with political processes, and share experience and expertise so others can find creative responses to conflict. We make peace possible. OUR VISION OUR VALUES Our vision is to transform the way the COLLABORATION world resolves violent conflict so that people work together to build peaceful We work in partnership to tackle and inclusive societies. violence, exclusion, injustice and inequality. OUR PURPOSE CREATIVITY Our purpose is to bring people together We are imaginative and resourceful to find creative and sustainable paths in how we influence change. to peace. CHALLENGE We are not afraid to face difficult conversations and defy convention. COMMITMENT We are dedicated and resilient in the long journey to lasting peace. 2 | CONCILIATION RESOURCES WELCOME I am proud to share Conciliation Resources’ 2019 Annual Review, which marks our 25th year. We started out with two second hand computers and a vision to support people working to bring peace to their war-torn societies. We have grown into an organisation of over 60 skilled and committed staff, with a network of more than 80 partners, that is integrated into a global community of peer organisations – people who every day make building better peace a reality. -

Challenges to Economic Growth in Post-Conflict Environments

CHALLENGES TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN POST-CONFLICT ENVIRONMENTS NEW TRENDS IN HUMAN CAPITAL LOSS, AID EFFECTIVENESS, AND TRADE LIBERALIZATION Jonathan D. Brandon Tutor: Xavier Fernández Pons Treball Final de Màster Màster d’Internacionalització Facultat d'Economia i Empresa Universitat de Barcelona Abril 2018 Abstract: The UNDP estimates that 526,000 people die each year as a result of violent conflict, making conflict deterrence a top priority for the international community. Immediately following a major conflict, countries that stagnate in economic growth have a 40% risk of conflict recurrence, yet those who successfully maintain high economic growth see their risk reduced to 25%. Due to this, stimulating growth should be a top priority in any economic reconstruction model. This paper aims to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of selected stimulants of economic growth: foreign direct investment, trade and financial liberalization, developmental assistance, and humanitarian aid. The subsequent macroeconomic responses are evaluated throughout the sample of 30 conflicts terminated between 1989 and 2014. This paper also explores the social and economic impacts of conflict and violence and develops a new indicator, the Human Capital Loss index, to quantify conflict intensity levels within the sample. Post-conflict countries require strong surges of investment, aid, and debt relief immediately following war, and those in the low income country (LIC) grouping require substantially greater efforts on the part of the international community -

'The Bougainville Conflict: a Classic Outcome of the Resource-Curse

The Bougainville conflict: A classic outcome of the resource-curse effect? Michael Cornish INTRODUCTION Mismanagement of the relationship between the operation of the Panguna Mine and the local people was a fundamental cause of the conflict in Bougainville. It directly created great hostility between the people of Bougainville and the Government of Papua New Guinea. Although there were pre-existing ethnic and economic divisions between Bougainville and the rest of Papua New Guinea, the mismanagement of the copper wealth of the Panguna Mine both exacerbated these existing tensions and provided radical Bougainvilleans an excuse to legitimise the pursuit of violence as a means to resolve their grievances. The island descended into anarchy, and from 1988 to 1997, democracy and the rule of law all but disappeared. Society fragmented and economic development reversed as the pillage and wanton destruction that accompanied the conflict took its toll. Now, more than 10 years since the formal Peace Agreement1 and over 4 years since the institution of the Autonomous Bougainville Government, there are positive signs that both democracy and development are repairing and gaining momentum. However, the untapped riches of the Panguna Mine remain an ominous issue that will continue to overshadow the region’s future. How this issue is handled will be crucial to the future of democracy and development in Bougainville. 1 Government of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea and Leaders representing the people of Bougainville, Bougainville Peace Agreement , 29 August 2001 BACKGROUND Bougainville is the name of the largest island within the Solomon Islands chain in eastern Papua New Guinea, the second largest being Buka Island to its north. -

Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube Analyzing the Success of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) Russell W. Glenn Prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command Approved for public release; distribution unlimited NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command. -

DT-S PDM LN199-91 Chinese China Trends of Qigong Research At

Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 DEf:'-ENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY WASHINGTON. O. C. 20301 TRANSLA TION REQUESTER TRANSLATOR'S INITIALS TRANSLATION NUMBER F.NCLlS) TO I R NO. DT-S PDM LN199-91 LANGUAGE GEOGRAPHIC AREA (11 dlflerent t,om place ot publl chinese China ENGLISH TITLE OF TRANSLATION AGE NOS. TRANSLATED FROM ORIG DOC. Trends of Qigong Research at Home the paat ten years 22 pages FOREIGN TITLE OF TRANSLATION SG6A AUTHOR IS) FOREIGN TITLE OF DOCUMENT (Complete only if dif{erent Irom title 01 translation) Bejing TImmunity Research Center. Beijing PUBLISHER DATE AND PLACE OF PUBLICATION COMMENTS TRANSLATION DIA FORM Almr-AM ease 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 Trends of Qigong Research at Home and Abroad in the Past Ten Years Beijing Immunity Research Center, Beijing. Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 Approved For Release 2001/03/07 : CIA-RDP96-00792R000200650023-0 LN199-91 Trends of Qigong Research at Home and Abroad in the Past Ten Years Development of Qi9:on!l-.!.~,:!g"!~~".J:llHt~~p~,s.t ten years from 1_~.29 to 1988 ha§__ ~~~__ :t::l_l}p'!,~9..edented l.n Ql.gong history. -

This Entire Document

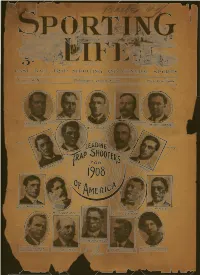

BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Volume 50, No. 17. Philadelphia, January 4, 1908. Price, Five Cents. __/ ^^-p^BS^^ / 5CMPOWCRS i GFOMMAXWELL ANTJAAY 4, I9O8J for illegally conducting a saloon in this catcher Cliff Blank/fenship, of the Washing city. "Breit" was taken into custody on ton Club, up for a like period. This is food December 23 by the sheriff. He was re enough for thought! and ball men are frank leased immediately on his own recognizance, to admit that there will be trouble ahead but will have to stand trial. Breitenstein if the Pacific Coast League directors are has been conducting a thirst emporium not up and doing. Some months ago it was here since the Southern League season reported that the (putlaw league was gradu NEW YORK STATE LEAGUE©S closed. He was warned two or three times ally growing. It looks now as though the by friends that he was placing himself in a time is fast arriving when the National NEXT MEET, precarious position by not heeding the Commission will Have to take a most de laws of the state, but refused to be warned. cisive stand or else the -Coast League will His arrest followed. He realizes now that be forced to abandon organized ball and go he is in bad and said today that if he got back to outlawry. The Disposition of the A* J* G* out of this scrajpe he would certainly lead The National Commission Unani the simple life in the future. He is going to play ball in New Orleans again next sea THE XRI-STATE LEAGUE Franchise the Important Matter son, but hasn©t signed his contract as yet. -

Ethnic Conflict in Papua New Guinea

Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 49, No. 1, April 2008 ISSN 1360-7456, pp12–22 Ethnic conflict in Papua New Guinea Benjamin Reilly Centre for Democratic Institutions, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract: On many measures of ethno-linguistic diversity, Papua New Guinea is the most frag- mented society in the world. I argue that the macro-level political effect of this diversity has been to reduce, rather than increase, the impact of ethnic conflict on the state. Outside the Bougainville conflict, and (to a lesser extent) the recent upsurge of violence in the Southern Highlands, ethnic conflicts in Papua New Guinea have not presented a threat to national government. In contrast to most other ethnically diverse societies, the most consequential impacts of ethnic conflict in Papua New Guinea are at the local level. This paper therefore examines the disparate impacts of local- and national-level forms of ethnic conflict in Papua New Guinea. Keywords: diversity, elections, ethnic conflict, Papua New Guinea Papua New Guinea combines two unusual fea- impact of ethnic conflict on the state. The reason tures which should make it a case of special for this is relatively straightforward: outside the interest to scholars of ethnicity and ethnic con- Bougainville conflict and (to a lesser extent) the flict. First, it boasts one of the developing recent upsurge of violence in the Southern High- world’s most impressive records of democratic lands, ethnic conflicts in Papua New Guinea longevity, with more than 40 years of continu- have not presented a threat to national govern- ous democratic elections, all of them chara- ment. -

2012-2013 National Peace Essay Contest

2012-2013 National Peace Essay Contest Womanhood in Peacemaking: Taking Advantage of Unity through Cultural Roles for a Successful Gendered Approach in Conflict Resolution by Bo Yeon Jang Overseas United States Institute of Peace page 1 / 11 2012-2013 National Peace Essay Contest "Womanhood in Peacemaking: Taking Advantage of Unity through Cultural Roles for a Successful Gendered Approach in Conflict Resolution" In January 1998, 50 women from opposing sides of the Bougainville Conflict successfully presented a female perspective in the negotiations of the Lincoln Agreement.[1] Consistent participation of women helped establish a permanent peace through collectively using their roles in society for unified initiatives. Conversely, Cote d’Ivoire failed to achieve resolution for its 2002 civil war[2]. Though Cote d’Ivoire struggled for a gendered approach to peacemaking, polarization around ethnicity and perceived deviation from cultural roles hindered its effectiveness. Inclusion of women in peacemaking was attempted in both the Bougainville Conflict and the First Ivorian Civil War, but their relative successes were determined significantly by the degree of unity in gendered actions and deference to cultural norms. These two cases show that gender inclusion contributes greatly to peacemaking processes and is essential to sustainable conflict resolution. Bougainville is an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea which completed its weapons disposal program and held a transparent first election in May 2005[3], finally stepping into long-term stability. From 1989 to 1998, a violent conflict sparked by mining rights between the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and the Papua New Guinea Defense Forces (PNGDF) raged in the region, leaving over 15,000 dead[4].