Download Ecuador-En.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CONQUEST of the INCAS Grade Levels: 8-13+ 30 Minutes AMBROSE VIDEO PUBLISHING 1995

#3593 THE CONQUEST OF THE INCAS Grade Levels: 8-13+ 30 minutes AMBROSE VIDEO PUBLISHING 1995 DESCRIPTION In 1532, Francisco Pizarro and a band of 170 conquistadors, searching for gold, embarked on the conquest of the Incan empire. Though badly outnumbered, they kidnapped Atahualpa, the god-king, and held him captive for nine months before murdering him. Reenactments and graphics help describe Incan civilization and its destruction. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: World History ¨ Standard: Understands major global trends from 1000 to 1500 CE · Benchmark: Understands differences and similarities between the Inca and Aztec empires and empires of Afro-Eurasia (e.g., political institutions, warfare, social organizations, cultural achievements) ¨ Standard: Understands how the transoceanic interlinking of all major regions of the world between 1450 and 1600 led to global transformations · Benchmark: Understands features of Spanish exploration and conquest (e.g., why the Spanish wanted to invade the Incan and Aztec empires, and why these empires collapsed after the conflict with the Spanish; interaction between the Spanish and indigenous populations such as the Inca and the Aztec; different perspectives on Cortes' journey into Mexico) · Benchmark: Understands cultural interaction between various societies in the late 15th and 16th centuries (e.g., how the Church helped administer Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas; reasons for the fall of the Incan empire to Pizarro; how the Portuguese dominated seaborne trade in the Indian Ocean basin in the 16th century; the relations between pilgrims and indigenous populations in North and South America, and the role different religious sects played in these relations; how the presence of Spanish conquerors affected the daily lives of Aztec, Maya, and Inca peoples) INSTRUCTIONAL GOALS 1. -

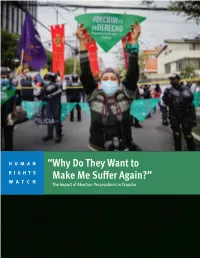

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

The Colombia-Ecuador Crisis of 2008

WAR WITHOUT BORDERS: THE COLOMBIA-ECUADOR CRISIS OF 2008 Gabriel Marcella December 2008 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the U.S. Government as defined in Title 17, United States Code, Section 101. As such, it is in the public domain, and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, Section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) publications are available on the SSI homepage for electronic dissemination. Hard copies of this report also may be ordered from our homepage. SSI’s homepage address is: www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil. ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please subscribe on our homepage at www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army. mil/newsletter/. ISBN 1-58487-372-8 ii FOREWORD Unprotected borders are a serious threat to the security of a number of states around the globe. -

Examining Leadership in Ecuador from an Interdisciplinary Contingency Perspective

Examining Leadership in Ecuador from an Interdisciplinary Contingency Perspective Cultural, Social, and Ethical Issues Key Words: Ecuador, Leadership, Culture Abstract This paper explores the foundations upon which modern Ecuadorian leadership culture is based by examining the historical elements of the Ecuadorian leadership cultural system from a contingency perspective, beginning with an overview of the historical context followed by an exploration of leadership and followership within this context. In so doing, it lays a foundation for further examination of leadership culture in Ecuador. Introduction One of the major factors that contributes to the success of any organizational venture is the leadership climate in which it takes place. Leadership scholars have long recognized the importance of not only the role of the leader, but also the importance of followers and the context in relation to achieving organizational goals (Lussier & Achua, 2007). Consequently, any examination of organizational efforts in Ecuador should begin with an examination and understanding of the leadership culture in which these efforts take place. This paper explores the foundations upon which modern Ecuadorian leadership culture is based by examining the historical elements of the Ecuadorian leadership cultural system from a contingency perspective, beginning with an overview of the historical context followed by an exploration of leadership and followership within this context. Contingency Approaches to Leadership The contingency approaches to leadership emerged as a trend in leadership studies that marked a fundamental shift in the way scholars thought about leadership. Prior to the contingency movement, the focus of leadership studies was centered on the traits, skills, behaviors, and styles of leaders (Ayman, 2004; P. -

Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador

Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador By David Heath Cooper Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Mehrangiz Najafizadeh ________________________________ Dr. Robert Antonio ________________________________ Dr. Ebenezer Obadare Date Defended: April 18th, 2014 The Thesis Committee for David Heath Cooper certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Mehrangiz Najafizadeh Date approved: April 18th, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Since the 1990s, the Ecuadorian Indigenous movement has transformed the nation's political landscape. CONAIE, a nationwide pan-Indigenous organization, and its demands for plurinationalism have been at the forefront of this process. For CONAIE, the demand for a plurinational refounding of the state is meant as both as a critique of and an alternative to what the movement perceives to be an exclusionary and Eurocentric nation-state apparatus. In this paper, my focus is twofold. I first focus on the role of CONAIE as the central actor in organizing and mobilizing the groundswell of Indigenous activism in Ecuador. After an analysis of the historical roots of the movement, I trace the evolution of CONAIE from its rise in the 1990s, through a period of decline and fragmentation in the early 2000s, and toward possible signs of resurgence since 2006. In doing so, my hope is to provide a backdrop from which to better make sense both of CONAIE's plurinational project and of the implications of the 2008 constitutional recognition of Ecuador as a plurinational state. -

The Fiscal and Monetary History of Ecuador: 1950–2015

WORKING PAPER · NO. 2018-65 The Fiscal and Monetary History of Ecuador: 1950–2015 Simón Cueva and Julían P. Díaz AUGUST 2018 1126 E. 59th St, Chicago, IL 60637 Main: 773.702.5599 bfi.uchicago.edu The Fiscal and Monetary History of Ecuador: 1950{2015∗ Sim´onCueva Juli´anP. D´ıaz TNK Economics Department of Economics Quinlan School of Business Loyola University Chicago July 2018 Abstract We document the main patterns in Ecuador's fiscal and monetary policy during the 1950{2015 period, and conduct a government's budget constraint accounting exercise to quantify the sources of deficit financing. We find that, prior to the oil boom of the 1970s, the size of the government and its financing needs were small, and the economy exhibited high growth rates and low inflation. The oil boom led to a massive increase in government spending. The oil prices crash of the early 1980s was not accompanied by any substantial fiscal correction, and the government considerably relied on seigniorage as a source of revenue. This coin- cided with almost three decades of high inflation rates and stagnant output. The dollarization regime, implemented in 2000, removed the ability of the government to resort to seigniorage to cover its imbalances. Indeed, in spite of large deficits registered since 2007, inflation has remained at historically low levels. However, the recent policies of inflated spending|and the heavy borrowing needed to fi- nance it|remind those that led to the collapse of the economy during the 1980s and 1990s, and generate concerns regarding the long-term sustainability of the dollarization regime, and of the benefits it has provided. -

Changes in the Foreign Policy of Bolivia and Ecuador: Domestic and International Conditions

Changes in the Foreign Policy of Bolivia and Ecuador: Domestic and International Conditions André Luiz Coelho Farias de Souza1 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1632-0098 Clayton M. Cunha Filho2 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6073-3570 Vinicius Santos3 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0907-7832 1Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Department of Political Studies, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brazil 2Universidade Federal do Ceará, Department of Social Sciences, Fortaleza/CE, Brazil 3Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte/MG, Brazil The aim of this paper is to assess the changes in the foreign policy of Bolivia and Ecuador during the administrations of Evo Morales (2006- 2019) and Rafael Correa (2007-2017), taking into account the interaction between domestic and international factors in both countries. Our working hypothesis argues that the reorientation of the foreign policy of these countries was possible due to a connection between alterations observed in the domestic and international spheres starting in the middle of the 2000s. In the internal sphere, the greater political stability resulting from the restructuring of the party system; in the foreign policy environment, an international system more open to the progressive field, allowing a change in the orientation of Bolivian and Ecuadorian foreign policy, based on that moment on the diversification of partnerships with an anti-United States bias. Keywords: Ecuador; Bolivia, Foreign Policy; Evo Morales; Rafael Correa. http://doi.org/ 10.1590/1981-3821202000030004 For data replication, see: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/T8YQH1 Correspondence: André Luiz Coelho Farias de Souza. E-mail: [email protected] This publication is registered under a CC-BY Licence. -

The Perversion of Rule of Law in Ecuador Daniela Salazar* 1

Salazar “My Power in the Constitution:” the Perversion of Rule of Law in Ecuador Daniela Salazar* 1. Introduction In 1830, Ecuador’s first president, Juan José Flores, appeared in a portrait wearing a silk sash, upon which was embroidered in gold letters the slogan: “My Power in the Constitution.” Since then, though with some changes of style, presidential sashes in Ecuador have kept that phrase intact, a characteristic which differentiates the sashes from others in the region. The meaning of the presidential slogan, nevertheless, has changed significantly. This phrase, which in its time referred to the importance of adhering to the Constitution as a limitation of power, today has taken on a more literal meaning: the power of the president, not the president’s limitations, resides in the Constitution. In the process that led to the adoption of the Constitution, and in the constitutional text itself, it is possible to find the keys to understanding the growing authoritarianism in Ecuador. With some frequency, those who recognize the excesses of presidential authority in Ecuador attribute them to the personality of President Rafael Correa, to his confrontational and populist style. Without claiming to carry out an exhaustive analysis of the extensive, complex, and imaginative Ecuadorian Constitution, in this essay I will allude to some examples of its innovations to demonstrate that the root of the perversion of rule of law in Ecuador does not lie in the leadership of the President, but rather in the 2008 Constitution itself, also known as the Constitution of Montecristi. It is my intention that the case of Ecuador and the examples 1 Salazar described here serve to inspire deeper reflection on the implications of the so-called new Latin American constitutionalism and its unfulfilled promises. -

Ecuador's Financial Rollercoaster

Boom & Bust: Ecuador’s Financial Rollercoaster The Interplay between Finance, Politics and Social Conditions in 20th century Ecuador Pablo R. Izurieta Andrade Copyright © 2015 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942450 ISBN: 978-1-62273-470-2 Images used with permission. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the author nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Synopsis This work proposes a connection of financial circumstances with major socio-political events in 20th-century Ecuador. It highlights the state of the nation’s economy as a determinant factor in the outcome of events. Throughout the history of Ecuador, the ambivalent evolution of major political and social events such as the stability of serving presidents, coups and war, has had an interesting and direct relationship to the financial environment. If the economy was healthy, did the country also experience stability? If it went into disarray, did the non-financial environment follow? Data collected from the Central Bank of Ecuador, unpublished diplomatic papers, and personal documents from relevant historical figures, as well as from the work of previous historians, indicate a strong effect of financial and economic performance on major political and social events. -

Original Paper the Role of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces

REPATS, Brasília/Brazil, Special Issue, nº 02, p. 50-72, Jul-Dec., 2019. Original Paper Received: June 26, 2019 Accepted: July 12, 2019 The Role of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces: Historical Structure and Changing Security Environments Katalina Barreiro Santana* Milton Reyes Herrera** Diego Pérez Enríquez*** Abstract This work addresses the central points of the construction process of the Ecuadorian Armed Forces to the new challenges, perceptions and responses related to the present environment of security and defense, from a structural and long-term historical perspective, which allows the understanding of this institution as key component of the complex Ecuadorian State-society, and its relations with different moments in the world and regional order. As an introductory point, a historical reading is presented, addressing the period between the conformation of the Republic to the culmination of the delimitation of its land border; in a second moment, the Pre and Pos scenario of the Peace Treaty with Peru from 1998 to 2007 will be analyzed; later it reviews the scenarios, * Professor and researcher at Instituto de Altos Estudios Nacionales del Ecuador -Ecuadorean National Institute of Advanced Studies - (IAEN). PHD in Political Science and Public Administration from Cuyo University, Argentina. Actually she is the Vice Chancellor of IAEN, the public graduate University of the State of Ecuador. ([email protected]) ** Professor and Researcher at the Security and Defense Center, Coordinator for the Security and Defense master’s program, and Coordinator of Chinese Studies Center in Ecuadorean National Institute of Advanced Studies (IAEN). Professor at Sociology Department, International Relations Program in Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. -

The Columbia-Ecuador Crisis of 2008

WAR WITHOUT BORDERS: THE COLOMBIA-ECUADOR CRISIS OF 2008 Gabriel Marcella December 2008 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the U.S. Government as defined in Title 17, United States Code, Section 101. As such, it is in the public domain, and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, Section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) publications are available on the SSI homepage for electronic dissemination. Hard copies of this report also may be ordered from our homepage. SSI’s homepage address is: www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil. ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please subscribe on our homepage at www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army. mil/newsletter/. ISBN 1-58487-372-8 ii FOREWORD Unprotected borders are a serious threat to the security of a number of states around the globe. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights and Trade Relations

High-Level Working Group on U.S.-Ecuador Relations Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Trade Relations: A Historical Perspective August 2021 HIGH-LEVEL WORKING GROUP ON U.S.-ECUADOR RELATIONS Tulio Vera Nathalie Cely Suárez Co-Chair Co-Chair Chile – Former Managing Director and Chief Ecuador – Former Ambassador of Ecuador Investment Strategist for the J.P. Morgan to the United States (JPM) Latin America Private Bank Veronica Arias Richard Feinberg Co-Chair Co-Chair Ecuador – Former Secretary of United States - Professor at the School of Environment of the Metropolitan District of Global Policy and Strategy, University of Quito California, San Diego Caterina Costa Luis Gilberto Murillo-Urrutia Co-Chair Co-Chair Ecuador – President of the Industrial Colombia – Former Minister of Group Poligrup Environment and Sustainable Development of Colombia and former Governor of Chocó, Colombia Guy Mentel Ezequiel Carman Project Director Lead Researcher United States – Executive Director of Argentina – Global Americans Trade Global Americans Lead Abelardo Pachano, Ecuador – Former Luis Enrique García, Bolivia – Former General Manager of the Central Bank of Executive President of CAF – Ecuador Development Bank of Latin America Anibal Romero, United States – Founder Luis Felipe Duchicela, Ecuador – Former of the Romero Firm Global Advisor on Indigenous Peoples at the World Bank Carolina Barco, Colombia – Former Foreign Minister of Colombia and former Luis Gilberto Murillo-Urrutia, Ambassador of Colombia to the United Colombia – Former Minister of States Environment