515627 Journal of Space Law 37.2 R2.Ps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Practical Guide Second Edition

TOURISTS in SPACE A Practical Guide Second Edition Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space A Practical Guide Other Springer-Praxis books of related interest by Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space: A Practical Guide 2008 ISBN: 978-0-387-74643-2 Lunar Outpost: The Challenges of Establishing a Human Settlement on the Moon 2008 ISBN: 978-0-387-09746-6 Martian Outpost: The Challenges of Establishing a Human Settlement on Mars 2009 ISBN: 978-0-387-98190-1 The New Space Race: China vs. the United States 2009 ISBN: 978-1-4419-0879-7 Prepare for Launch: The Astronaut Training Process 2010 ISBN: 978-1-4419-1349-4 Ocean Outpost: The Future of Humans Living Underwater 2010 ISBN: 978-1-4419-6356-7 Trailblazing Medicine: Sustaining Explorers During Interplanetary Missions 2011 ISBN: 978-1-4419-7828-8 Interplanetary Outpost: The Human and Technological Challenges of Exploring the Outer Planets 2012 ISBN: 978-1-4419-9747-0 Astronauts for Hire: The Emergence of a Commercial Astronaut Corps 2012 ISBN: 978-1-4614-0519-1 Pulling G: Human Responses to High and Low Gravity 2013 ISBN: 978-1-4614-3029-2 SpaceX: Making Commercial Spacefl ight a Reality 2013 ISBN: 978-1-4614-5513-4 Suborbital: Industry at the Edge of Space 2014 ISBN: 978-3-319-03484-3 Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space A Practical Guide Second Edition Dr. Erik Seedhouse, Ph.D., FBIS Sandefjord Norway SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION ISBN 978-3-319-05037-9 ISBN 978-3-319-05038-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-05038-6 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937810 1st edition: © Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2008 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 This work is subject to copyright. -

The Space Race Continues

The Space Race Continues The Evolution of Space Tourism from Novelty to Opportunity Matthew D. Melville, Vice President Shira Amrany, Consulting and Valuation Analyst HVS GLOBAL HOSPITALITY SERVICES 369 Willis Avenue Mineola, NY 11501 USA Tel: +1 516 248-8828 Fax: +1 516 742-3059 June 2009 NORTH AMERICA - Atlanta | Boston | Boulder | Chicago | Dallas | Denver | Mexico City | Miami | New York | Newport, RI | San Francisco | Toronto | Vancouver | Washington, D.C. | EUROPE - Athens | London | Madrid | Moscow | ASIA - 1 Beijing | Hong Kong | Mumbai | New Delhi | Shanghai | Singapore | SOUTH AMERICA - Buenos Aires | São Paulo | MIDDLE EAST - Dubai HVS Global Hospitality Services The Space Race Continues At a space business forum in June 2008, Dr. George C. Nield, Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), addressed the future of commercial space travel: “There is tangible work underway by a number of companies aiming for space, partly because of their dreams, but primarily because they are confident it can be done by the private sector and it can be done at a profit.” Indeed, private companies and entrepreneurs are currently aiming to make this dream a reality. While the current economic downturn will likely slow industry progress, space tourism, currently in its infancy, is poised to become a significant part of the hospitality industry. Unlike the space race of the 1950s and 1960s between the United States and the former Soviet Union, the current rivalry is not defined on a national level, but by a collection of first-mover entrepreneurs that are working to define the industry and position it for long- term profitability. -

Following the Path That Heroes Carved Into History: Space Tourism, Heritage, and Faith in the Future

religions Article Following the Path That Heroes Carved into History: Space Tourism, Heritage, and Faith in the Future Deana L. Weibel Departments of Anthropology and Integrative, Religious, and Intercultural Studies, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 29 November 2019; Accepted: 28 December 2019; Published: 2 January 2020 Abstract: Human spaceflight is likely to change in character over the 21st century, shifting from a military/governmental enterprise to one that is more firmly tied to private industry, including businesses devoted to space tourism. For space tourism to become a reality, however, many obstacles have to be overcome, particularly those in finance, technology, and medicine. Ethnographic interviews with astronauts, engineers, NASA doctors, and NewSpace workers reveal that absolute faith in the eventual human occupation of space, based in religious conviction or taking secular forms, is a common source of motivation across different populations working to promote human spaceflight. This paper examines the way faith is expressed in these different contexts and its role in developing a future where space tourism may become commonplace. Keywords: anthropology; tourism; spaceflight; NASA; heritage; exploration 1. Introduction Space tourism is an endeavor, similar to but distinctly different from other forms of space travel, that relies on its participants’ and brokers’ faith that carrying out brave expeditions, modeled on and inspired by those in the past, will ultimately pay off in a better future for humankind. Faith, in this case, refers to a subjective sense that a particular future is guaranteed and may or may not have religious foundations. This faith appears to be heightened by the collective work undertaken by groups endeavoring to send humans into space, creating a sense of what anthropologists Victor and Edith Turner have described as communitas, a shared feeling of equality and common purpose. -

Espinsights the Global Space Activity Monitor

ESPInsights The Global Space Activity Monitor Issue 1 January–April 2019 CONTENTS SPACE POLICY AND PROGRAMMES .................................................................................... 1 Focus .................................................................................................................... 1 Europe ................................................................................................................... 4 11TH European Space Policy Conference ......................................................................... 4 EU programmatic roadmap: towards a comprehensive Regulation of the European Space Programme 4 EDA GOVSATCOM GSC demo project ............................................................................. 5 Programme Advancements: Copernicus, Galileo, ExoMars ................................................... 5 European Space Agency: partnerships continue to flourish................................................... 6 Renewed support for European space SMEs and training ..................................................... 7 UK Space Agency leverages COMPASS project for international cooperation .............................. 7 France multiplies international cooperation .................................................................... 7 Italy’s PRISMA pride ................................................................................................ 8 Establishment of the Portuguese Space Agency: Data is King ................................................ 8 Belgium and Luxembourg -

Spacewatchafrica March Edition

Nancy Matimu appointed new Multichoice Kenya CEO VVVolVolVolVol o6 o6 66l l. .No. NoNo. No78 N N 55 oo5.. 2 March 2018 2020 AFRICA Nigeria AFRICA Has local content policy any impact on the Space sector? Africa Magic Channels Aand ne wthe le ariseder aofn dNollywood player in the aerospace industry C O N T E N T S Vol. 8 No. 2 Streamlining licensing procedures for small satellites Enabel partners SES to connect foreign aid projects in Editor in-chief Aliyu Bello Africa via satellite Executive Manager Tonia Gerrald Ethiopia joins Africa’s space race SA to the editor in-Chief Ngozi Okey NTA plans infrastructural upgrade Head, Application Services M. Yakubu Editorial/ICT Services John Daniel MultiChoice in Zambian economy Usman Bello Reviewing US ban of Indian PSLV Alozie Nwankwo Viasat visits Nigeria on readiness to deploy broadband services Juliet Nnamdi Client Relations Sunday Tache Globalstar announces 2019 fourth quarter Lookman Bello annual results Safiya Thani Nancy Matimu appointed new Multichoice Kenya CEO Marketing Offy Pat Meteorologists to learn satellite monitoring skills Tunde Nathaniel Wasiu Olatunde Google announces US$1 million African Media Relations Favour Madu internet safety fund Khadijat Yakubu Intelsat announces fourth quarter and full-year 2019 results Zacheous Felicia Has local content policy any impact Finance Folarin Tunde on the Space sector? Egypt and the "space race” Space Watch Magazine is a publication of Communication Science, Inc. All correspondence should be addressed to editor, space Watch Magazine. Abuja office: Plot 2009, Awka Street, UTC Building, GF 11, Area 10, Garki, Abuja, Nigeria Tel: 234 80336471114, 07084706167, email: [email protected] LEGAL CONSULTANTS Idowu Oriola & Co. -

Wgcapd-10 Final Report

CEOS Working Group on Capacity Building and Data Democracy (WGCapD) 10th Annual Meeting: Building a Vision for the Next Decade 1 to 4 March 2021, Virtual Celebrating 10 years of… WGCapD 0 CEOS Working Group on Capacity Development and Data Democracy 10th Annual Meeting Report Contents Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Key insights and recommendations .......................................................................................................... 2 Capacity building gaps, recommendations, and ideas that WGCapD might consider in concert with other CEOS working teams ....................................................................................................................... 3 Next steps ................................................................................................................................................. 4 WGCapD-10 in detail ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Internal working sessions.......................................................................................................................... 5 Keynote ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Session 2: EO capacity development in the decade ahead ..................................................................... -

Bachelorarbeit ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BACHELORARBEIT ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Frau ! ! Sarah Weß Das touristische Potential der Raumfahrt innerhalb der nächsten 10–15 Jahre 2014! ! ! ! ! ! ! Fakultät: Medien ! BACHELORARBEIT! ! ! ! ! ! ! Das touristische Potential der Raumfahrt innerhalb der nächsten 10–15 Jahre Autor/in: Frau Sarah Weß Studiengang: Business Management Seminargruppe: BM11wT1-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. h.c. Lothar Otto Zweitprüfer: Tasillo Römisch Einreichung: Wietmarschen, 24.06.2014! ! ! ! ! ! ! Faculty of Media ! BACHELOR THESIS! ! ! ! ! ! ! The touristic potential of space flight within the next 10–15 years. author: Ms. Sarah Weß course of studies: Business Management seminar group: BM11wT1-B first examiner: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. h.c. Lothar Otto second examiner: Tasillo Römisch submission: Wietmarschen, 24.06.2014! Bibliografische Angaben Weß, Sarah Das touristische Potential der Raumfahrt innerhalb der nächsten 10–15 Jahre. The touristic potential of space flight within the next 10–15 years. 56 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2014 Abstract In dieser Arbeit beschäftigt sich die Verfasserin Sarah Weß mit dem touristischen Po- tential der Raumfahrt innerhalb der nächsten 10–15 Jahre. Es wird außerdem der Fra- ge nachgegangen, ob der Weltraumtourismus zugelassen werden kann, oder ob es nicht angesichts der Auswirkungen doch besser wäre, den „Spaßfaktor“ hinten anzu- stellen. Ziel ist es, eine Entscheidungshilfe bezüglich dieser Frage zu bieten. Ihr unter- geordnet werden Fragen -

Winter/Spring 2021 [email protected] • • (207) 389-4606 Newsletter #40

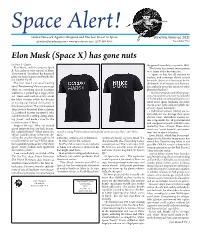

Space Alert! Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space Winter/Spring 2021 [email protected] • www.space4peace.org • (207) 389-4606 Newsletter #40 Elon Musk (Space X) has gone nuts by Bruce K. Gagnon the general assembly accepted in 1962. Elon Musk, and his company Space The treaty has several major points X, has a plan to take control of Mars. to it. Some of the key ones are: They want to ‘Terraform’ the dusty red • Space is free for all nations to planet to make it green and livable like explore, and sovereign claims cannot our Mother Earth. be made. Space activities must be for The first time I can recall hearing the benefit of all nations and humans. about Terraforming Mars was years ago (So, nobody owns the moon or other while on a speaking tour in Southern planetary bodies.) California. I picked up a copy of the • Nuclear weapons and other weap- LA Times and read an article about ons of mass destruction are not allowed the Mars Society, which has dreams in Earth orbit, on celestial bodies or in of moving our human civilization to other outer-space locations. (In other this faraway planet. The article quoted words, peace is the only acceptable use Mars Society President Robert Zubrin of outer-space locations). • Individual nations (states) are re- (a Lockheed Martin executive), who sponsible for any damage their space called the Earth “a rotting, dying, stink- objects cause. Individual nations are ing planet” and made a case for the also responsible for all governmental transformation of Mars. -

Commercial Spaceflight: the “Ticket to Ride”

Commercial Spaceflight: The “Ticket to Ride” By Pamela L. Meredith and Marshall M. Lammers ommercial human space- Operator, where possible, will want a separate contract flight is soon upon us, with the SFP, including a release, to ensure compliance Cperhaps only a few years with the CSLA and applicable state law and to shield away. Virgin Galactic, XCOR itself from liability. Unless otherwise specified, this Aerospace, and Rocketplane article refers to the spaceflight purchase contract Global are already taking reserva- (whether the SFP or the Sponsor is the buyer) and/or tions for human suborbital space- any additional contract with the SFP as the “Contract.” flight.1 Virgin Galactic reportedly The Contract likely will cover these, among other, has signed up over 500 passengers––so-called space- topics: the spaceflight services being provided, space- flight participants (SFPs)2—and could be ready for com- flight safety, SFP health and fitness requirements, price mercial flight as early as 2013.3 Blue Origin is yet and payment conditions, the SFP’s duties, and risk allo- another prospective spaceflight operator.4 cation and insurance provisions. This article will touch One can speculate on precisely what a spaceflight upon some of the legal issues raised by these provi- “ticket to ride” will look like, but this much may be sions, with a particular focus on CSLA compliance and safe to assume: contractual risk allocation. • It will comply with the Commercial Space Launch Act5 (CSLA), which mandates that the spaceflight Spaceflight Services operator (Operator): (1) inform the SFP about the The Contract with the SFP and/or Sponsor will safety aspects of the spaceflight and obtain his or describe the spaceflight services that the Operator her written “informed consent,” (2) execute liabili- agrees to provide. -

Forging Commercial Confidence

SPACEPORT UK: AHEAD FORGING WITH COMMERCIAL CONFIDENCE Copyright © Satellite Applications Catapult Ltd 2014. SPACEPORT UK: FORGING AHEAD WITH COMMERCIAL CONFIDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 07 2 DEMAND FORECAST 11 • Commercial human spaceflight • Very high speed point to point travel • Satellite deployment • Microgravity research • Other commercial demand 3 SPACEPORT FACILITIES 47 • Core infrastructure required • Spaceflight preparation and training • Tours/visitor centre • Space campus • Key findings 4 WIDER ECONOMIC IMPACT 57 • Summary • Site development • Employment • Tourism • R&D/education • Key findings 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT 67 • Unlocking commercial potential 6 RISKS 73 • Accidents • Single operator • Local opposition 7 FINANCING 77 • Existing scenario • Potential funding sources • Other sources of funds • Insurance • Key findings Appendices 85 • Appendix A • Appendix B Acknowledgements and contact information 89 5 Spaceport UK: A pillar of growth for the UK and European space industry, enabling lower cost access to space, and creating economic benefit far beyond its perimeter fence. A spaceport will unlock economic growth and jobs in existing UK industries and regions, while positioning the UK to take advantage of emerging demand for commercial human spaceflight, small satellite launch, microgravity research, parabolic flights, near-space balloon tourism, and eventually high-speed point-to-point travel. Without a specific site selected and looking at the economic impact of a spaceport generically, this report expects the spaceport to deliver approximately £2.5bn and 8,000 jobs to the broader UK economy over 10 years. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Executive Summary Our plan is for Britain to have a fully functional, operating spaceport “by 2018. This would serve as a European focal point for the pioneers of commercial spaceflight using the potential of spaceflight experience companies like Virgin Galactic, XCOR and Swiss S3 to pave the way for satellite launch services to follow. -

Espinsights the Global Space Activity Monitor

ESPInsights The Global Space Activity Monitor Issue 3 July–September 2019 CONTENTS FOCUS ..................................................................................................................... 1 A new European Commission DG for Defence Industry and Space .............................................. 1 SPACE POLICY AND PROGRAMMES .................................................................................... 2 EUROPE ................................................................................................................. 2 EEAS announces 3SOS initiative building on COPUOS sustainability guidelines ............................ 2 Europe is a step closer to Mars’ surface ......................................................................... 2 ESA lunar exploration project PROSPECT finds new contributor ............................................. 2 ESA announces new EO mission and Third Party Missions under evaluation ................................ 2 ESA advances space science and exploration projects ........................................................ 3 ESA performs collision-avoidance manoeuvre for the first time ............................................. 3 Galileo's milestones amidst continued development .......................................................... 3 France strengthens its posture on space defence strategy ................................................... 3 Germany reveals promising results of EDEN ISS project ....................................................... 4 ASI strengthens -

Space Warfare and Defense by Chapman

SPACE WARFARE AND DEFENSE www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 SPACE WARFARE AND DEFENSE A Historical Encyclopedia and Research Guide BERT CHAPMAN Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an ebook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 Production Editor: Alisha Martinez Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Manager: Caroline Price Media Editor: Julie Dunbar File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is printed on acid-free paper. Manufactured in the United States of America www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 To Becky, who personifies Proverbs 31:10. www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 www.abc-clio.com ABC-CLIO 1-800-368-6868 C ONTENTS Acknowledgements ix Introduction xi Chronology xv PART 1 1 Development of U.S. Military Space Policy 3 2 U.S.