Contemporary Criminological Issues Moving Beyond Insecurity and Exclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

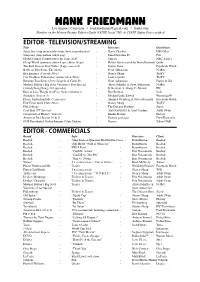

Hank Friedmann CV

HANK FRIEDMANN Los Angeles, California • [email protected] • hankf.com Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (IATSE Local 700) & CSATF Safety Pass certified ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - TELEVISION/STREAMING Title Directors Distributor Santa, Inc (stop motion television show, in production) - Harry Chaskin HBO Max Simpsons (stop motion couch gag) - John Harvatine IV Fox Global Citizen Countdown to the Prize 2020 - Various NBC & Int’l Gloop World (animatic editor 5 eps, editor 15 eps) - Helder Sun (created by Justin Roiland) Quibi The Real Bros of Simi Valley (5 eps, season 3) - Jimmy Tatro Facebook Watch Between Two Ferns: The Movie - Scott Aukerman Netflix Blackspiracy (Comedy Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Can You Beat Yamaneika? (Game Show Pilot) - Lauren Quinn TruTV Between Two Ferns (Jerry Seinfeld & Cardi B.) - Scott Aukerman Funny or Die Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special - Akiva Schaffer & Scott Aukerman Netflix Comedy Bang Bang (110 episodes) - B. Berman, S. Sharp, D. Jelinek IFC How to Lose Weight in 4 Easy Steps (Sundance) - Ben Berman Jash Snatchers (Season 3) - Michael Lukk Litwak Warner/go90 Please Understand Me (5 episodes) - Ahamed Weinberg & Steven Feinartz Facebook Watch End Times Girls Club (Pilot) - Stoney Sharp TruTV Flulanthropy - The Director Brothers Seeso Cool Dad (TV Special) - Alex Kavutskiy & Ariel Gardner Adult Swim Crossroads of History “Lincoln” - Marko Slavnic History American Idol Season 10 & 11 - Remote packages Ford/Fremantle GOP Presidential Online Internet Cyber Debate - Various Yahoo!/FoD ____________________________________________________________________________ EDITOR - COMMERCIALS Brand Info Directors Client Reebok - Allen Iverson/Question Mid Double Cross - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - Gigi Hadid “Wild is Wherever” - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - FW19 Trail - Roundhouse Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B: Aztrek” - Eric Notarnicola Reebok Reebok - “Cardi B vs. -

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cer�fied Organisa�On)

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (IS/ISO 9001: 2015 Cerfied Organisaon) Annual Report 2017-18 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan, Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, (Old Minto Road), New Delhi-110002 Telephone : +91-11-23664147 Fax No:+91-11-23211046 Website:hp://www.trai.gov.in LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To the Central Government through Hon’ble Minister of Communicaons and Informaon Technology It is my privilege to forward the 21st Annual Report for the year 2017-18 of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India to be laid before both Houses of Parliament. Included in this Report is the informaon required to be forwarded to the Central Government under the provisions of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997, as amended by TRAI (Amendment) Act, 2000. The Report contains an overview of the telecom and broadcasng sectors and a summary of the key iniaves of TRAI on regulatory maers with specific reference to the funcons mandated to it under the Act. The Audited Annual Statement of Accounts of TRAI is also included in the Report. (RAM SEWAK SHARMA) CHAIRPERSON Dated: September 2018 III TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl.No. Parculars Page Nos. Overview of the Telecom and Broadcasng Sectors 1-8 Policies and Programmes 9-60 A. Review of General Environment in the Telecom Sector Part – I B. Review of Policies and Programmes C. Annexures to Part – I Part – II Review of working and operaon of the Telecom 61-130 Regulatory Authority of India Part – III Funcons of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India in respect of maers 131-150 specified in Secon 11 of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act Part – IV Organizaonal maers of Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and 151-220 Financial performance A. -

Introduction Since Opening Its Doors in 2007

RCMP Heritage Centre National Museum Status Project Project Management RFP Introduction Since opening its doors in 2007, Regina’s RCMP Heritage Centre has engaged thousands of visitors in the story of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and its important role throughout our nation’s history. The Centre’s collections are curated and displayed within an impressive 70,000 square foot facility that has become a provincial architectural icon standing proudly next to the RCMP Training Academy, ‘Depot’ Division. With the support of the Federal Government, the Centre is preparing to write an ambitious new chapter of our story as we take the steps necessary to be recognized as a national museum. To ensure the success of this important initiative, the Board of Directors has chosen to engage a project manager to assist with the planning, coordination, and execution of various tasks and initiatives expected to arise in support of the process. The project manager’s mandate will be to support the realization of the Board’s vision for the Centre as a recognized national museum, completing the process in advance of the 150th anniversary of the RCMP in 2023. RCMP Heritage Centre Overview RCMP members are born all over the world, but they are made in Regina, Saskatchewan at RCMP Training Academy, ‘Depot’ Division. The training centre, the only one of its kind in Canada, has long been of interest to visitors, friends and families of members alike. The RCMP have been training the best and the brightest on its grounds since 1885. Living next door to “Depot” and “F” Division is the majestic RCMP Heritage Centre. -

The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 98 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 The onsC titutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hill Indiana University-Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Hill, John Lawrence (2009) "The onC stitutional Status of Morals Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 98 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol98/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TKenf]iky Law Jornal VOLUME 98 2009-2010 NUMBER I ARTICLES The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hiff TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE HARM PRINCIPLE A. Some Difficulties with the Concept of "MoralsLegislation" B. The Near Irrelevance of the PhilosophicDebate C. The Concept of "Harm" II. DEFINING THE SCOPE OF THE PRIVACY RIGHT IN THE CONTEXT OF MORALS LEGISLATION III. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE PROBLEMS OF RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW A. The 'RationalRelation' Test in Context B. The Concept of a Legitimate State Interest IV. MORALITY AS A LEGITIMATE STATE INTEREST: FIVE TYPES OF MORAL PURPOSE A. The Secondary or IndirectPublic Effects of PrivateActivity B. Offensive Conduct C. Preventingthe Corruptionof Moral Character D. ProtectingEssential Values andSocial Institutions E. -

Political Reelism: a Rhetorical Criticism of Reflection and Interpretation in Political Films

POLITICAL REELISM: A RHETORICAL CRITICISM OF REFLECTION AND INTERPRETATION IN POLITICAL FILMS Jennifer Lee Walton A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2006 Committee: John J. Makay, Advisor Richard Gebhardt Graduate Faculty Representative John T. Warren Alberto Gonzalez ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to discuss how political campaigns and politicians have been depicted in films, and how the films function rhetorically through the use of core values. By interpreting real life, political films entertain us, perhaps satirically poking fun at familiar people and events. However, the filmmakers complete this form of entertainment through the careful integration of American values or through the absence of, or attack on those values. This study provides a rhetorical criticism of movies about national politics, with a primary focus on the value judgments, political consciousness and political implications surrounding the films Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), The Candidate (1972), The Contender (2000), Wag the Dog (1997), Power (1986), and Primary Colors (1998). iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank everyone who made this endeavor possible. First and foremost, I thank Doctor John J. Makay; my committee chair, for believing in me from the start, always encouraging me to do my best, and assuring me that I could do it. I could not have done it without you. I wish to thank my committee members, Doctors John Warren and Alberto Gonzalez, for all of your support and advice over the past months. -

Myth Making, Juridification, and Parasitical Discourse: a Barthesian Semiotic Demystification of Canadian Political Discourse on Marijuana

MYTH MAKING, JURIDIFICATION, AND PARASITICAL DISCOURSE: A BARTHESIAN SEMIOTIC DEMYSTIFICATION OF CANADIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE ON MARIJUANA DANIEL PIERRE-CHARLES CRÉPAULT Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Criminology Department of Criminology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa © Daniel Pierre-Charles Crépault, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 ABSTRACT The legalization of marijuana in Canada represents a significant change in the course of Canadian drug policy. Using a semiotic approach based on the work of Roland Barthes, this dissertation explores marijuana’s signification within the House of Commons and Senate debates between 1891 and 2018. When examined through this conceptual lens, the ongoing parliamentary debates about marijuana over the last 127 years are revealed to be rife with what Barthes referred to as myths, ideas that have become so familiar that they cease to be recognized as constructions and appear innocent and natural. Exploring one such myth—the necessity of asserting “paternal power” over individuals deemed incapable of rational calculation—this dissertation demonstrates that the processes of political debate and law-making are also a complex “politics of signification” in which myths are continually being invoked, (re)produced, and (re)transmitted. The evolution of this myth is traced to the contemporary era and it is shown that recent attempts to criminalize, decriminalize, and legalize marijuana are indices of a process of juridification that is entrenching legal regulation into increasingly new areas of Canadian life in order to assert greater control over the consumption of marijuana and, importantly, over the risks that this activity has been semiologically associated with. -

Healthcare in Regina

Healthcare in Regina Regina and Saskatchewan have a deep-rooted history in ensuring good, accessible healthcare is available for all its people. While under Canada’s free healthcare model, anyone in need has the ability to access healthcare at any stage of their lives and any stage of their health. Saskatchewan Health Authority Find a Doctor The Saskatchewan Health Authority launched in 2017, transitioning Looking to find a doctor in Regina? We have great healthcare 12 former regional authorities to a single provincial one. It is the professionals available who are accepting new patients. largest organization in Saskatchewan, and one of the most integrated Find a Doctor rqhealth.ca/facilities/doctors-accepting-new-patients health delivery agencies in the country. The Saskatchewan Health Authority offers a full range of hospital, rehabilitation, community and public health, long term care and home care services to meet Emergency Services the needs of everyone in Saskatchewan, regardless of where they reside in the province. The Saskatchewan Health Authority provides emergency medical services through first responders and ambulance services for Regina For more information, visit www.saskhealthauthority.ca and surrounding rural communities. Our emergency number is 911. Hospitals and Clinics Learn More rqhealth.ca/departments/ems-emergency-medical-services Regina has two main hospitals located around the center of the city, as well as many walk-in clinics throughout the city. Pediatricians Regina General Hospital rqhealth.ca/facilities/regina-general-hospital The Saskatchewan Health Authority provides inpatient, outpatient, Pasqua Hospital rqhealth.ca/facilities/pasqua-hospital and emergency services for children under 18 years of age in hospitals and clinics throughout Regina. -

Government Enforcement of Morality : a Critical Analysis of the Devlin-Hart Controversy. Peter August Bittlinger University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 Government enforcement of morality : a critical analysis of the Devlin-Hart controversy. Peter August Bittlinger University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Bittlinger, Peter August, "Government enforcement of morality : a critical analysis of the Devlin-Hart controversy." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1909. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1909 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOVERNMENT ENFORCEMENT OF MORALITY A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE DEVLIN-HART CONTROVERSY A Dissertation Presented By PETER AUGUST BITTLINGER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 Political Science Peter August Bittlinger I976 All Rights Reserved GOVERNMENT ENFORCEMENT OF MORALITY A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE DEVLIN-HART CONTROVERSY A Dissertation Presented By PETER AUGUST BITTLINGER Approved as to style and content by: Felix E. Grppenheim, Chairman •Loren P. Beth, Member Lawrence Foster, Member ( /^IA Loren P. Beth, Head -

An Application of Bayesian Model Averaging with Rural Crime Data ______

International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory, Vol. 4, No. 2, December 2011, 683-717 Model Uncertainty in Ecological Criminology: An Application of Bayesian Model Averaging With Rural Crime Data ___________________________________________________________________________________ Steven C. Dellera Lindsay Amielb Melissa Dellerc Abstract In this study we explore the use of Bayesian model averaging (BMA) to address model uncertainty in identifying the determinants of Midwestern rural crime rates using county level data averaged over 2006-07-08. The empirical criminology literature suffers from serious model uncertainty: theory states that everything matters and there are multiple ways to measure key variables.By using the BMA approach we identify variables that appear to most consistently influence rural crime patterns. We find that there are several variables that rise to the top in explaining different types of crime as well as numerous variables that influence only certain types of crime. Introduction The empirical ecological criminology literature is vast and richly interdisciplinary. But there are at least three problem areas that have created significant confusion over the policy implications of this literature. First, the theoretical literature basically concludes that “everything matters” which makes empirical investigations difficult specifically related to model uncertainty. Second, there is sufficient fragility within the empirical results to cast a pall over the literature (Chiricos, 1987; Patterson, 1991; Fowles and Merva, 1996; Barnett and Mencken, 2002; Bausman and Goe, 2004; Chrisholm and Choe, 2004; Messner, Baumer and Rosenfeld, 2004; Phillips, 2006; Authors). Donohue and Wolfers (2005) along with Cohen-Cole, Durlauf, Fagan and Nagin (2009) note, for example, that the extensive empirical literature seeking to test the deterrent effect of capital punishment has yield nothing but contradictory and inconclusive results. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

It's Jerry's Birthday Chatham County Line

K k JULY 2014 VOL. 26 #7 H WOWHALL.ORG KWOW HALL NOTESK g k IT’S JERRY’S BIRTHDAY On Friday, August 1, KLCC and Dead Air present an evening to celebrate Jerry Garcia featuring two full sets by the Garcia Birthday Band. Jerry Garcia, famed lead guitarist, songwriter and singer for The Grateful Dead and the Jerry Garcia Band, among others, was born on August 1, 1941 in San Francisco, CA. Dead.net has this to say: “As lead guitarist in a rock environment, Jerry Garcia naturally got a lot of attention. But it was his warm, charismatic personality that earned him the affection of millions of Dead Heads. He picked up the guitar at the age of 15, played a little ‘50s rock and roll, then moved into the folk acoustic guitar era before becoming a bluegrass banjo player. Impressed by The Beatles and Stones, he and his friends formed a rock band called the Warlocks in late 1964 and debuted in 1965. As the band evolved from being blues-oriented to psychedelic/experi- mental to adding country and folk influences, his guitar stayed out front. His songwriting partnership with Robert Hunter led to many of the band’s most memorable songs, including “Dark Star”, “Uncle John’s Band” and the group’s only Top 10 hit, “Touch of Grey”. Over the years he was married three times and fathered four daughters. He died of a heart attack CHATHAM COUNTY LINE in 1995.” On Sunday, July 27, the Community Tightrope also marks a return to Sound Fans have kept the spirit of Jerry Garcia alive in their hearts, and have spread the spirit Center for the Performing Arts proudly wel- Pure Studios in Durham, NC, where the and the music to new generations. -

Easy Money; Being the Experiences of a Reformed Gambler;

^EASY MONEY Being the Experiences of a Reformed Gambler All Gambling Tricks Exposed \ BY HARRY BROLASKI Cleveland, O. SEARCHLIGHT PRESS 1911 Copyrighted, 1911 by Hany Brolaski -W.. , ,-;. j jfc. HV ^ 115^ CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Pages Introductory : 9-10 CHAPTE-R II. My* First Bet 11-25 CHAPTER III. The Gambling Germ Grows—A Mother's Love 26-5S CHAPTER IV. Grafter and Gambler—Varied Experiences 59-85 CHAPTER V. A Race Track and Its Operation 86-91 CHAPTER VI. Race-track Grafts and Profits —Bookmakers 92-104 CHAPTER VII. Oral Betting 106-108 CHAPTER VIII. Pool-rooms 109-118 CHAPTER IX. Hand-books 119-121 CHAPTER X. Gambling Germ 122-123 CHAPTER XI. Malevolence of Racing 124-125 CHAPTER XII. Gambling by Employees 126-127 CHAPTER XIII. My First Race Horse 128-130 CHAPTER XIV. Some Race-track Experiences—Tricks of the Game 131-152 CHAPTER XV. Race-track Tricks—Getting the Money 153-162 7 — 8 Contents. CHAPTER XVI. Pages Women Bettors 163-165 CHAPTER XVII. Public Choice 166 CHAPTER XVIII. Jockeys 167-174 CHAPTER XIX. Celebrities of the Race Track 175-203 CHAPTER XX. The Fight Against Race Tracks. 204-219 CHAPTER XXI Plague Spots in American Cities 220-234 CHAPTER XXII. Gambling Inclination of Nations 235-237 CHAPTE-R XXIII. Selling Tips 238-240 CHAPTER XXIV. Statement Before United States Senate Judiciary- Committee—Race-track Facts and Figures International Reform Bureau 241-249 CHAPTER XXV. Gambling on the Mississippi River 250-255 CHAPTER XXVI. Gambling Games and Devices 256-280 CHAPTER XXVII. Monte Carlo and Roulette 281-287 CHAPTER XXVIII.