Initially Achieved a Balance of Power with Sweyn's Son, Cnut. The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Pilgrimage to Nidaros

rway S o o Nidaros pirit N Path t ual Jo y to m’s ugust 4 urne gri A -13, 2020 e Pil Hiking th Hosted by P hoto cr edit: Vis it Norway The Rev Sonja Hagander Augsburg University Vice President, Highlights & Inclusions Mission & Identity Experience spiritual enrichment and fellowship as part of The Rev. Sonja Hagander served as pastor at Augsburg a traveling community under the leadership, teaching and University for 21 years and now leads a new Division of hospitality of The Rev. Sonja Hagander. Mission & Identity. She led an interfaith group of students to Norway in 2017. Ever since serving as a Boundary Waters Be inspired hiking part of the Nidaros Pilgrimage route, Canoe Area guide during college, she has been interested in the the beautiful Gudbrandsdalen path, one of the eight St. Olav’s intersection between sacred texts, spirituality and the out-door Paths ending at Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. world. Sonja recently experienced this pilgrim trail during a visit this past summer. Stay in select accommodations for nine nights, based on sharing a room in hotels and lodges described in the itinerary. Pilgrimage Hike Physical Journey throughout in a private, deluxe motorcoach from Lillehammer to Trondheim. Baggage along the hiking route and Gear Requirements is transported by the motorcoach daily. This travel program is for experienced hikers, preferably with Enjoy 21 meals including buffet breakfast, eight dinners and mountain hiking. The amount of hiking is up to 12.5 miles four boxed lunches. during a day (see August 7) and at steep inclines of up to 1,000 feet during a day (see August 9). -

Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral: Competition Manual

Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral: Competition Manual Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral Site information and energy data (v.13 april) Official competition website: http://climate-kic.org/nidaros 1 Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral: Competition Manual TABLE OF CONTENT General information about Nidaros Cathedral 4 Cultural heritage conservation and energy consumption 11 Energy consumption of Nidaros Cathedral 13 The surroundings in a historic neighborhood 17 A unique and important urban challenge for the City of Trondheim 24 List of attachments (to be downloaded separately) 01 Architecture and technical drawings 02 Energy consumption 2014 – 2017 03 Outdoor temperature Trondheim Voll station 2014-2017 04 Indoor temperature 03.2016-04.2018 05 Maps of district heating systems 2 Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral: Competition Manual Organizing partners Trondheim Municipality Nidaros Cathedral Restoration Workshop (NDR) EIT Climate-KIC Associated partners The Common Church Council in Trondheim Technoport 3 Energy-Smart Nidaros Cathedral: Competition Manual General information about Nidaros Cathedral History and architecture Nidaros Cathedral is the world’s northernmost medieval cathedral and Norway’s national sanctuary. It is the grave church of St. Olav, the patron Saint of Norway and has now become one of Europe’s major historical pilgrim destinations. Nidaros Cathedral is also where coronations and royal blessings take place. The cathedral is mainly built in soapstone. It is located on the foundations of former churches, and the oldest standing parts of the church, the transepts, are from about 1160-70. The church is rebuilt with brick vaults over the choir and western nave, and across the archways under the triforium. The copper-covered roof is carried by steel structures with the exception of the transepts, the chapter house and the extended chapels in the transepts which all have pure wood structures in the roof. -

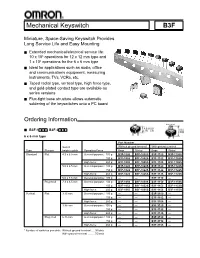

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Wessex and the Reign of Edmund Ii Ironside

Chapter 16 Wessex and the Reign of Edmund ii Ironside David McDermott Edmund Ironside, the eldest surviving son of Æthelred ii (‘the Unready’), is an often overlooked political figure. This results primarily from the brevity of his reign, which lasted approximately seven months, from 23 April to 30 November 1016. It could also be said that Edmund’s legacy compares unfavourably with those of his forebears. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon Kings of England whose lon- ger reigns and periods of uninterrupted peace gave them opportunities to leg- islate, renovate the currency or reform the Church, Edmund’s brief rule was dominated by the need to quell initial domestic opposition to his rule, and prevent a determined foreign adversary seizing the throne. Edmund conduct- ed his kingship under demanding circumstances and for his resolute, indefati- gable and mostly successful resistance to Cnut, his career deserves to be dis- cussed and his successes acknowledged. Before discussing the importance of Wessex for Edmund Ironside, it is con- structive, at this stage, to clarify what is meant by ‘Wessex’. It is also fitting to use the definition of the region provided by Barbara Yorke. The core shires of Wessex may be reliably regarded as Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berk- shire and Hampshire (including the Isle of Wight).1 Following the victory of the West Saxon King Ecgbert at the battle of Ellendun (Wroughton, Wilts.) in 835, the borders of Wessex expanded, with the counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex passing from Mercian to West Saxon control.2 Wessex was not the only region with which Edmund was associated, and nor was he the only king from the royal House of Wessex with connections to other regions. -

1 Clontarf 1014

Clontarf 1014 – a battle of the clans? 1. The contemporary record In its account of the battle of Clontarf the northern AU report that Brian, son of Cennétig, king of Ireland, and Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Tara, led an army to Dublin (Áth Cliath) • all of the Leinsterman (Laigin) were assembled to meet him (Brian), the foreigners of Áth Cliath, and a similar number of foreigners of Lochlainn (Scotland) • a sterling battle was fought between them, the like of which had never been encountered before Then the foreigners and the Leinstermen first broke in defeat and were completely wiped out • there fell on the side of the foreign troop Máel Mórda, king of Leinster, and Domnall, king of the Forthuatha • of the foreigners fell Dubgall, son of Amlaíb (= Óláfr), Sigurd, earl (jarl) of Orkney, and Gilla Ciaráin, heir designate of the foreigners, etc. • Brodar who slew Brian, chief of the Scandinavian fleet, together with 6,000 others was also killed or drowned Of the Irish who fell in the counter-shock were Brian, overking of the Irish of Ireland and of the foreigners [of Limerick and Waterford] and of the Britons [of Wales?], the Augustus of the whole of the north-west of Europe [= Ireland] • his son Murchad and the latter’s son Tairdelbach, Conaing, the heir designate of Mumu, Mothla, king of the Déisi Muman, etc. • the list includes numerous kings of various parts of Munster, plus Domnall, the earl of Marr in Scotland • this list carries conviction when analysed against known details The southern AI report similarly, though more -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

ANGLO-SAXON CHARTERS (July 2018) Add Ch 19788 Sawyer 67

ANGLO-SAXON CHARTERS (July 2018) Add Ch 19788 Sawyer 67 624? King Wulfhere Worcester Add Ch 19789 Sawyer 56 759 Eanberht etc Worcester Add Ch 19790 Sawyer 139 8th century King Offa Worcester Add Ch 19791 Sawyer 1281 904 Bishop Werferth Worcester Add Ch 19792 Sawyer 1326 969 Bishop Oswald Worcester Add Ch 19793 Sawyer 772 969 King Edgar Worcester Add Ch 19794 Sawyer 1347 984 Archbishop Oswald Worcester Add Ch 19795 Sawyer 1385 11th century Archbishop Wulfstan Worcester Add Ch 19796 Sawyer 1423 11th century Abbot Ælfweard Worcester Add Ch 19797 Sawyer 1399 11th century Bishop Brihtheah Worcester Add Ch 19798 Sawyer 1393 1038 Bishop Lyfing Worcester Add Ch 19799 Sawyer 1394 1042 Bishop Lyfing Worcester Add Ch 19800 Sawyer 1407 c. 1053 Bishop Ealdred Worcester Add Ch 19801 Sawyer 1405 1058 Bishop Ealdred Worcester Add Ch 19802 Sawyer 1156 1062 Edward the Confessor Worcester Add Ch 28657 Sawyer 1098 11th century Edward the Confessor Coventry Add Ch 33686 Sawyer 798, 974; 1062 King Edgar etc Ramsey 1030, 1109, 1110 Add MS 7138 Sawyer 1451a 10th century Plegmund Narrative Exeter Cotton Ch IV 18 Sawyer 451 925 King Æthelstan Beverley Cotton Ch VI 2 Sawyer 1043 1066 Edward the Confessor Westminster Cotton Ch VI 4 Sawyer 266 761 King Æthelberht Rochester Cotton Ch VII 6 Sawyer 1121 11th century Edward the Confessor Westminster Cotton Ch VII 13 Sawyer 1141 11th century Edward the Confessor Westminster Cotton Ch VIII 3 Sawyer 96 757 King Æthelbald Malmesbury Cotton Ch VIII 4 Sawyer 264 778 King Cynewulf Cotton Ch VIII 6 Sawyer 550 949 King Eadred -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis.