Boroondara Thematic Environmental History 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Hilary Grove, Glen Iris Place Type: Residential Buildings (Private), House Significance Level: Local

‘St Hilary’, formerly ‘Charleville’ 2 Hilary Grove, Glen Iris Place type: Residential Buildings (private), House Significance level: Local Recommended protection: Planning Scheme Architectural style: Victorian period (1851-1901) Georgian & Italianate Locality history Glen Iris is a suburb that lies at the northern end of the former City of Malvern. It occupies gently undulating country along the Gardiners Creek valley, and is bounded by Tooronga Road, Wattletree Road and the Monash Freeway. The hamlet of Gardiner now lies within Glen Iris, although this was formerly recognised as a locality of its own. Glen Iris has long straddled two municipalities, with a portion in the former City of Malvern and a portion in the former City of Camberwell (now the City of Boroondara). It was originally bisected by the Gardiners Creek but in the 1960s the South Eastern freeway created a wider barrier between the two sections. York Street, Glen Iris, for example, is now in two disconnected sections. The first settlement in this area took advantage of the Gardiners Creek, which provided a water source for stock, and for orchards and market gardens. The line of the creek, and the roads that followed it, including Malvern Road, became an eastwards arterial of early settlement. The first land sales in the mid-1850s attracted those seeking an elevated suburban retreat away from the noise and odours of the city, and the early estates operated as small farms. Among the notable early estates were ‘Charleville’ (1857), ‘Viewbank’ (c.1858-59) and ‘Brymawr’ (1859). The area was highly desirable on account of the picturesque countryside and commanding views. -

City of Port Phillip Flag Protocol

PORT PHILLIP CITY COUNCIL FLAG PROTOCOL The Australian national flag, will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole on every day of the year from the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls in accordance with the Flag Act 1953, with the following exceptions subject to the advice of the Chief Executive Officer: UNITED NATIONS DAY The United Nations flag will be flown all day on United Nations Day (24 October) at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls. As part of an agreement made by the Australian Government as a member of the United Nations, the United Nations flag is to be flown in the position of honour all day on United Nations Day, displacing the Australian National flag for that day. SORRY DAY The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Sorry Day (26 May). NATIONAL ABORIGINAL AND ISLANDERS’ DAY OBSERVANCE COMMITTEE (NAIDOC WEEK) The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to NAIDOC Week (first week of July). PRIDE MARCH The Rainbow Flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Pride March (January, nominated week). -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Town and Country Planning Board of Victoria

1965-66 VICTORIA TWENTIETH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING BOARD OF VICTORIA FOR THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1964, TO 30rH JUNE, 1965 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 5 (2) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1961 [Appro:timate Cost of Report-Preparation, not given. Printing (225 copies), $736.00 By Authority A. C. BROOKS. GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE. No. 31.-[25 cents]-11377 /65. INDEX PAGE The Board s Regulations s Planning Schemes Examined by the Board 6 Hazelwood Joint Planning Scheme 7 City of Ringwood Planning Scheme 7 City of Maryborough Planning Scheme .. 8 Borough of Port Fairy Planning Scheme 8 Shire of Corio Planning Scheme-Lara Township Nos. 1 and 2 8 Shire of Sherbrooke Planning Scheme-Shire of Knox Planning Scheme 9 Eildon Reservoir .. 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Alexandra) 10 Eildon Reservoir Planning Scheme (Shire of Mansfield) 10 Eildon Sub-regional Planning Scheme, Extension A, 1963 11 Eppalock Planning Scheme 11 French Island Planning Scheme 12 Lake Bellfield Planning Scheme 13 Lake Buffalo Planning Scheme 13 Lake Glenmaggie Planning Scheme 14 Latrobe Valley Sub-regional Planning Scheme 1949, Extension A, 1964 15 Phillip Island Planning Scheme 15 Tower Hill Planning Scheme 16 Waratah Bay Planning Scheme 16 Planning Control for Victoria's Coastline 16 Lake Tyers to Cape Howe Coastal Planning Scheme 17 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Portland) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Belfast) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Warrnambool) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Heytesbury) 18 South-Western Coastal Planning Scheme (Shire of Otway) 18 Wonthaggi Coastal Planning Scheme (Borough of Wonthaggi) 18 Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme 19 Melbourne's Boulevards 20 Planning Control Around Victoria's Reservoirs 21 Uniform Building Regulations 21 INDEX-continued. -

CITY of BOROONDARA Review of B-Graded Buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn

CITY OF BOROONDARA Review of B-graded buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn Prepared for City of Boroondara January 2007 Revised June 2007 VOLUME 4 BUILDINGS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR THE HERITAGE OVERLAY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Main Report VOLUME 2 Individual Building Data Sheets – Kew VOLUME 3 Individual Building Data Sheets – Camberwell and Hawthorn VOLUME 4 Individual Building Data Sheets for buildings not recommended for the Heritage Overlay LOVELL CHEN 1 Introduction to the Data Sheets The following data sheets have been designed to incorporate relevant factual information relating to the history and physical fabric of each place, as well as to give reasons for the recommendation that they not be included in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay in the Boroondara Planning Scheme. The following table contains explanatory notes on the various sections of the data sheets. Section on data sheet Explanatory Note Name Original and later names have been included where known. In the event no name is known, the word House appears on the data sheet Reference No. For administrative use by Council. Building type Usually Residence, unless otherwise stated. Address Address as advised by Council and checked on site. Survey Date Date when site visited. Noted here if access was requested but not provided. Grading Grading following review (C or Ungraded). In general, a C grading reflects a local level of significance albeit a comparatively low level when compared with other examples. In some cases, such buildings may not have been extensively altered, but have been assessed at a lower level of local significance. In other cases, buildings recommended to be downgraded to C may have undergone alterations or additions since the earlier heritage studies. -

Moreland History Publications Books

MORELAND HISTORY PUBLICATIONS Some with notes. This list is a work in progress and should not be considered comprehensive. Last updated: 17 December 2012. Most of the following publications can be consulted at Moreland Libraries http://www.moreland.vic.gov.au/moreland-libraries.html Contents: Books Theses Periodicals Newspapers Heritage studies BOOKS Arranged in order of publication, earliest first. Jubilee history of Brunswick : and illustrated handbook of Brunswick and Coburg F.G. Miles Contributor(s): R. A Vivian ; Publisher: Melbourne : Periodicals Publishing Company Date(s): 1907 Description: 119p. : ill., ports. ; 29cm (photocopy). Subjects: City of Moreland, Brunswick (Vic.), Coburg (Vic.) Location: Brunswick Library history room 994.51 JUB Location: Coburg Library history room 994.51 MEL An index concerning the history of Brunswick No author or date. ‘This is an index of persons and subject names concerning the history of Brunswick. The index is based on the “Jubilee history of Brunswick” 1907.’ Location: Brunswick Library history room 994 INDE (SEE ALSO Index of the Jubilee history of Brunswick 1907 prepared by Merle Ellen Stevens 1979) Reports on Coburg Council meetings in local newspapers Oct 1912 to December 1915 No publication date so entered under publication of newspaper. Location: Coburg Library history room 352.09451 REP The City of Coburg : the inception of a new city : 1850-1922. Description [43 leaves] : ill., maps ; 30 cm. Subjects Coburg (Vic.) --History. Location: Coburg Library history room 994.51 CIT Coburg centenary 1839-1939, official souvenir: celebrations August - October, 1939 Walter Mitchell Coburg, Vic : Coburg City Council, 1939. 24 p. : ill., portraits, pbk ; 25 cm. -

__History of Kew Depot and It's Routes

HISTORY OF KEW DEPOT AND ITS ROUTES Page 1 HISTORY of KEW DEPOT and the ROUTES OPERATED by KEW Compiled and written by Hugh Waldron MCILT CA 1500 The word tram and tramway are derived from Scottish words indicating the type of truck and the tracks used in coal mines. 1807 The first Horse tram service in the world commences operation between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales. 12th September 1854 At 12.20 pm first train departs Flinders Street Station for Sandridge (Port Melbourne) First Steam operated railway line in Australia. The line is eventually converted to tram operation during December 1987 between the current Southbank Depot and Port Melbourne. The first rail lines in Australia operated in Newcastle Collieries operated by horses in 1829. Then a five-mile line on the Tasman Peninsula opened in 1836 and powered by convicts pushing the rail vehicle. The next line to open was on 18/5/1854 in South Australia (Goolwa) and operated by horses. 1864 Leonard John Flannagan was born in Richmond. After graduating he became an Architect and was responsible for being the Architect building Malvern Depot 1910, Kew Depot 1915 and Hawthorn Depot 1916. He died 2nd November 1945. September 1873 First cable tramway in the world opens in Clay Street, San Francisco, USA. 1877 Steam tramways commence. Victoria only had two steam tramways both opened 1890 between Sorrento Pier to Sorrento Back Beach closed on 20th March 1921 (This line also operated horse trams when passenger demand was not high.) and Bendigo to Eaglehawk converted to electric trams in 1903. -

Tovvn and COUN1'r,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD

1952 VICTORIA SEVENTH ANNUAL REPORT 01<' THE TOvVN AND COUN1'R,Y PL1\NNING 130ARD FOI1 THE PERIOD lsr JULY, 1951, TO 30rH JUNE, 1~)52. PHESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 4 (3) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLA},"NING ACT 1944. Appro:rima.te Cost of Repo,-1.-Preparat!on-not given. PrintJng (\l50 copieti), £225 ]. !'!! Jtutlt.ortt!): W. M. HOUSTON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 5.-[2s. 3d.].-6989/52. INDEX Page The Act-Suggested Amendments .. 5 Regulations under the Act 8 Planning Schemes-General 8 Details of Planning Schemes in Course of Preparation 9 Latrobe Valley Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 12 Abattoirs 12 Gas and Fuel Corporation 13 Outfall Sewer 13 Railway Crossings 13 Shire of Narracan-- Moe-Newborough Planning Scheme 14 Y allourn North Planning Scheme 14 Shire of Morwell- Morwell Planning Scheme 14 Herne's Oak Planning Scheme 15 Yinnar Planning Scheme 15 Boolarra Planning Scheme 16 Shire of Traralgon- Traralgon Planning Scheme 16 Tyers Planning Scheme 16 Eildon Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 17 Gelliondale Sub-Regional Planning Schenu• 17 Club Terrace Planning Scheme 17 Geelong and Di~triet Town Planning Scheme 18 Portland and DiHtriet Planning Scheme 18 Wangaratta Sub-Regional Planning Scheme 19 Bendigo and District Joint Planning Scheme 19 City of Coburg Planning Scheme .. 20 City of Sandringham Planning Seheme 20 City of Moorabbin Planning Scheme~Seetion 1 20 City of Prahran Plaml'ing Seheme 20 City of Camberwell Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Broadml'adows Planning Scheme 21 Shire of Tungamah (Cobmm) Planning Scheme No. 2 21 Shire of W odonga Planning Scheme 22 City of Shepparton Planning t::lcheme 22 Shire of W arragul Planning Seh<>liH' 22 Shire of Numurkah- Numurkah Planning Scheme 23 Katunga. -

General Order Dated 16 May 2005 Pdf 212.13 KB

ADMINISTRATION OF ACTS General Order 2005 I, Stephen Phillip Bracks, Premier of Victoria, state that the following administrative arrangements for responsibility for the following Acts, provisions of Acts and functions will operate in place of the arrangements in operation immediately before the date of this Order: 1 General Order 2005 Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Aboriginal Lands Act 1970 Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 2 General Order 2005 Minister for Aged Care Health Services Act 1988 – • Sections 99, 100, 101 and 103 • Sections 11, 102, 110 and 119 in so far as they relate to supported residential services (the sections are otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) • Part 5, jointly and severally administered with the Minister for Health except for section 119 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) 3 General Order 2005 Minister for Agriculture Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1992 Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Victoria) Act 1994 Agricultural Industry Development Act 1990 Biological Control Act 1986 Broiler Chicken Industry Act 1978 Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 – • In so far as it relates to the exercise of powers for the purposes of the Fisheries Act 1995 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Environment and the Minister for Planning) Control of Genetically Modified Crops Act 2004 Dairy Act 2000 Domestic (Feral and Nuisance) Animals Act 1994 Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 – • Part 4A (The -

Bridge Types in NSW Historical Overviews 2006

Bridge Types in NSW Historical overviews 2006 These historical overviews of bridge types in NSW are extracts compiled from bridge population studies commissioned by RTA Environment Branch. CONTENTS Section Page 1. Masonry Bridges 1 2. Timber Beam Bridges 12 3. Timber Truss Bridges 25 4. Pre-1930 Metal Bridges 57 5. Concrete Beam Bridges 75 6. Concrete Slab and Arch Bridges 101 Masonry Bridges Heritage Study of Masonry Bridges in NSW 2005 1 Historical Overview of Bridge Types in NSW: Extract from the Study of Masonry Bridges in NSW HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO MASONRY BRIDGES IN NSW 1.1 History of early bridges constructed in NSW Bridges constructed prior to the 1830s were relatively simple forms. The majority of these were timber structures, with the occasional use of stone piers. The first bridge constructed in NSW was built in 1788. The bridge was a simple timber bridge constructed over the Tank Stream, near what is today the intersection of George and Bridge Streets in the Central Business District of Sydney. Soon after it was washed away and needed to be replaced. The first "permanent" bridge in NSW was this bridge's successor. This was a masonry and timber arch bridge with a span of 24 feet erected in 1803 (Figure 1.1). However this was not a triumph of colonial bridge engineering, as it collapsed after only three years' service. It took a further five years for the bridge to be rebuilt in an improved form. The contractor who undertook this work received payment of 660 gallons of spirits, this being an alternative currency in the Colony at the time (Main Roads, 1950: 37) Figure 1.1 “View of Sydney from The Rocks, 1803”, by John Lancashire (Dixson Galleries, SLNSW). -

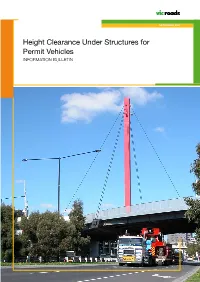

Height Clearance Under Structures for Permit Vehicles

SEPTEMBER 2007 Height Clearance Under Structures for Permit Vehicles INFORMATION BULLETIN Height Clearance A vehicle must not travel or attempt to travel: Under Structures for (a) beneath a bridge or overhead Permit Vehicles structure that carries a sign with the words “LOW CLEARANCE” or This information bulletin shows the “CLEARANCE” if the height of the clearance between the road surface and vehicle, including its load, is equal to overhead structures and is intended to or greater than the height shown on assist truck operators and drivers to plan the sign; or their routes. (b) beneath any other overhead It lists the roads with overhead structures structures, cables, wires or trees in alphabetical order for ready reference. unless there is at least 200 millimetres Map references are from Melway Greater clearance to the highest point of the Melbourne Street Directory Edition 34 (2007) vehicle. and Edition 6 of the RACV VicRoads Country Every effort has been made to ensure that Street Directory of Victoria. the information in this bulletin is correct at This bulletin lists the locations and height the time of publication. The height clearance clearance of structures over local roads figures listed in this bulletin, measured in and arterial roads (freeways, highways, and metres, are a result of field measurements or main roads) in metropolitan Melbourne sign posted clearances. Re-sealing of road and arterial roads outside Melbourne. While pavements or other works may reduce the some structures over local roads in rural available clearance under some structures. areas are listed, the relevant municipality Some works including structures over local should be consulted for details of overhead roads are not under the control of VicRoads structures. -

Lower Yarra River Corridor Study

Lower Yarra River Corridor Study YARRA MUNICIPAL TOOLKIT NOVEMBER 2016 Planisphere planning & urban design tel (03) 3419 7226 e-mail [email protected] Level 1/160 Johnston St Fitzroy VIC 3065 Find out more at www.planisphere.com.au Planisphere planning & urban design tel (03) 3419 7226 e-mail [email protected] Level 1/160 Johnston St Fitzroy VIC 3065 Find out more at www.planisphere.com.au © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning 2016 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ ISBN XXX X XXXX (Online) Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone the DELWP Customer Service Centre on 136186, email customer. [email protected] (or relevant address), or via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice. com.au. This document is also available on the internet at www.delwp.vic.gov.au Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication.