Understanding Port Melbourne: Accounting For, and Interrupting, Social Order in an Australian Suburb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Port Phillip Flag Protocol

PORT PHILLIP CITY COUNCIL FLAG PROTOCOL The Australian national flag, will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole on every day of the year from the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls in accordance with the Flag Act 1953, with the following exceptions subject to the advice of the Chief Executive Officer: UNITED NATIONS DAY The United Nations flag will be flown all day on United Nations Day (24 October) at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls. As part of an agreement made by the Australian Government as a member of the United Nations, the United Nations flag is to be flown in the position of honour all day on United Nations Day, displacing the Australian National flag for that day. SORRY DAY The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Sorry Day (26 May). NATIONAL ABORIGINAL AND ISLANDERS’ DAY OBSERVANCE COMMITTEE (NAIDOC WEEK) The Australian Aboriginal flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to NAIDOC Week (first week of July). PRIDE MARCH The Rainbow Flag will be flown at mast head from the highest flagpole at the St Kilda, South Melbourne and Port Melbourne Town Halls (displacing the Australian National flag) during and the week leading up to Pride March (January, nominated week). -

General Order Dated 16 May 2005 Pdf 212.13 KB

ADMINISTRATION OF ACTS General Order 2005 I, Stephen Phillip Bracks, Premier of Victoria, state that the following administrative arrangements for responsibility for the following Acts, provisions of Acts and functions will operate in place of the arrangements in operation immediately before the date of this Order: 1 General Order 2005 Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Aboriginal Lands Act 1970 Archaeological and Aboriginal Relics Preservation Act 1972 2 General Order 2005 Minister for Aged Care Health Services Act 1988 – • Sections 99, 100, 101 and 103 • Sections 11, 102, 110 and 119 in so far as they relate to supported residential services (the sections are otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) • Part 5, jointly and severally administered with the Minister for Health except for section 119 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Health) 3 General Order 2005 Minister for Agriculture Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1992 Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Victoria) Act 1994 Agricultural Industry Development Act 1990 Biological Control Act 1986 Broiler Chicken Industry Act 1978 Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 – • In so far as it relates to the exercise of powers for the purposes of the Fisheries Act 1995 (The Act is otherwise administered by the Minister for Environment and the Minister for Planning) Control of Genetically Modified Crops Act 2004 Dairy Act 2000 Domestic (Feral and Nuisance) Animals Act 1994 Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Act 1981 – • Part 4A (The -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10

Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10 Identifier Petrol filling station and Industrial premises Formerly Petrol filling station Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO283 Address Cnr. Salmon St and Williamstown Rd. Category Industrial PORT MELBOURNE Constructed 1938 Designer unknown Amendment C 32 Comment Map corrected Significance The petrol filling station and industrial premises of W. Rodgerson at the NW. corner of Salmon Street and Williamstown Road were built in 1938. They are aesthetically important as a rare surviving building of their type in the Streamlined Moderne mode (Criteria B and E), being enhanced by their intact state. Primary Source Andrew Ward, City of Port Phillip Heritage Review, 1998 Other Studies Description A petrol filling station and two storeyed industrial premises at the rear in the Streamlined Moderne manner with curved canopy and centrally situated office beneath with curved and rectangular corner windows symmetrically arranged. At the rear the industrial premises are of framed construction with dark mottled brick cladding enclosing steel framed window panels at ground floor level and plain stuccoed panels above. Condition: Sound. Integrity: High. History Crown land was released for sale at Fishermen's Bend in the 1930’s. William Rodgerson purchased lot 1 of Section 67C on the north west corner of Williamstown Road and Salmon Street. It comprised one acre. In 1938, Rodgerson built a service station on the site, which twenty years later he was still operating. From the early 1960’s, Rodgerson began a business as a cartage contractor. He worked out of the same premises as W.Rodgerson Pty Ltd. -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Identifier: Pier Hotel Citation No: Formerly: Pier Hotel 608 Address: 1 Bay Street, corner of Beach Street, Heritage Precinct Overlay: N/a PORT MELBOURNE Heritage Overlay: HO462 Category: Commercial Graded as: Significant Constructed: 1860s?/c. 1937 Designer: Unknown Amendment: C103 Comment: Updated citation History The first Pier Hotel on the subject site was established in September 1840 by Wilbraham Liardet, an early and prominent settler of Port Melbourne. Liardet had arrived at Port Melbourne in 1839.i He soon established a mail service from arriving ships to the township of Melbourne, and opened his timber hotel (the second at Sandridge), in September 1840, at a cost of £1300. ii The hotel was originally known as the Brighton Pier Hotel, apparently reflecting Liardet’s view that Sandridge be known as Brighton.iii By that summer, the Pier Hotel was described as a ‘magnificent house’, serving refreshments to those who arrived from Melbourne to visit the beach.iv Liardet’s fortunes soon fell, however, and he was declared bankrupt in January 1845.v He was unable to purchase the land on which his hotel stood at the first land sales of Sandridge in September 1850, and the allotment was instead purchased by DS Campbell and A Lyell.vi By 1857, the Pier Hotel comprised two sitting rooms, four bedrooms, a bar and four other rooms, and was rated with a net annual value of £350, and was owned by WJT Clarke and operated by James Garton. vii Clarke was a large landowner and prominent member of Victorian Colonial society, and a member of the Legislative Council between 1856 and 1870.viii City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Citation No: 608 Figure 1 Detail of a photograph of Bay Street Port Melbourne looking north, c. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10

Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 10 Identifier Petrol filling station and Industrial premises Formerly Petrol filling station Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO283 Address Cnr. Salmon St and Williamstown Rd. Category Industrial PORT MELBOURNE Constructed 1938 Designer unknown Amendment C 32 Comment Map corrected Significance The petrol filling station and industrial premises of W. Rodgerson at the NW. corner of Salmon Street and Williamstown Road were built in 1938. They are aesthetically important as a rare surviving building of their type in the Streamlined Moderne mode (Criteria B and E), being enhanced by their intact state. Primary Source Andrew Ward, City of Port Phillip Heritage Review, 1998 Other Studies Description A petrol filling station and two storeyed industrial premises at the rear in the Streamlined Moderne manner with curved canopy and centrally situated office beneath with curved and rectangular corner windows symmetrically arranged. At the rear the industrial premises are of framed construction with dark mottled brick cladding enclosing steel framed window panels at ground floor level and plain stuccoed panels above. Condition: Sound. Integrity: High. History Crown land was released for sale at Fishermen's Bend in the 1930’s. William Rodgerson purchased lot 1 of Section 67C on the north west corner of Williamstown Road and Salmon Street. It comprised one acre. In 1938, Rodgerson built a service station on the site, which twenty years later he was still operating. From the early 1960’s, Rodgerson began a business as a cartage contractor. He worked out of the same premises as W.Rodgerson Pty Ltd. -

Port Phillip Heritage Review

6. Heritage Overlay Areas 6.1 Introduction The heritage overlay areas constitute those areas within the Municipality that are considered to demonstrate a comparatively high level of cultural value when considered in terms of their historic, aesthetic and social attributes. They survive generally with a higher level of architectural integrity than the remaining areas of the municipality and it is not unlikely that they will have superior civic or aesthetic qualities. Given that Port Phillip has evolved over a long period, principally from the 1840’s until the inter-war period, these areas invariably exhibit the characteristics of their time, both in architectural and civic design terms, as well as functionally. In some instances, most notably St. Kilda, there is a diversity which imparts special character. All of the coastal areas identified in the Review, extending inland to Albert Park and Clarendon Street, South Melbourne, have cultural importance extending beyond the limits of Port Phillip. These areas impart identity to Melbourne as an international City and their management, as a consequence, places a heavy burden of responsibility on the shoulders of the community of Port Phillip and its Council. This burden is increased by the mounting pressures for change that reflect the desire of many to live in a coastal strip of limited capacity. The identification of these areas, therefore, represents an initial step in the development of the conservation strategy required to manage change in the interests of the very qualities which make them special places in which to live. The heritage overlay areas are shown below and are described in the sections, which follow. -

M~Gi5ltttiu~ Mountil. Lonsdale ·

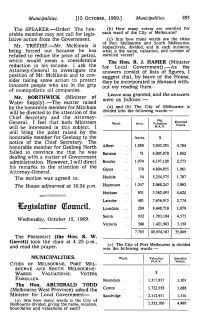

Municipalities. [15 OCTOBER, 1969.] Municipalities. 895 The SPEAKER.-Order! The hon (b) How many voters are enrolled for orable member may not call for legis each ward of the City of Melbourne? lative action from the Government. (c) Into how many wards are the cities of Port Melbourne and South Melbourne, Mr. TREZISE.-Mr. McKinnis is respectively, divided, and in each instance, being forced out because he has what is the name, valuation, and number of refused to reduce the price of petrol, enrolled voters? which would mean a considerable The Hon. R. J. HAMER (Minister reduction in his income. I ask the for Local Government) .-As the Attorney-General to investigate the answers consist of lists of figures, I position of Mr. McKinnis and to con suggest that, by leave of the House, sider taking some action to protect they be incorporated in Hansard with innocent people who are in the grip out my reading them. of monopolistic oil companies. Leave was granted, and the answers Mr. BORTHWICK (Minister of were as follows:- Water Supply) .-The matter raised by the honorable member for Mitcham (a) and (b) The City of Melbourne is will be directed to the attention of the divided into the following wards:- Chief Secretary and the Attorney Net Enrolled General. I feel that both Ministers Ward. Area. Valuation will be interested in this subject. I N.A.V. Voters. will bring the point raised by the honorable member for Geelong to the Acres. $ notice of the Chief Secretary. The honorable member for Geelong North Albert · . 1,088 3,030,295 4,784 failed to convince me that he was Batman · . -

The Places We Keep: the Heritage Studies of Victoria and Outcomes for Urban Planners

The places we keep: the heritage studies of Victoria and outcomes for urban planners Robyn Joy Clinch Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Architecture & Planning) June 2012 Faculty of Architecture, Building & Planning The University of Melbourne Abstract The incentive for this thesis that resulted from an investigation into the history of my heritage house, developed from my professional interest in the planning controls on heritage places. This was further motivated by my desire to reinvent my career as an urban planner and to use my professional experience in management, marketing and information technology. As a result, the aim of this thesis was to investigate the relationship between the development of the heritage studies of Victoria and the outcome of those documents on planning decisions made by urban planners. The methods used included a simulated experience that established a methodology for the thesis. In addition, interviews were conducted with experts in the field that provided a context for understanding the influencing factors of when, where, by whom, with what, why and how the studies were conducted. These interviews also contributed to the understanding of how the historical research had been undertaken and used to establish the significance of places and how this translated into outcomes for urban planners. Case studies in the form of Tribunal determinations have been used to illustrate key outcomes for urban planners. A large amount of information including that relating to the historical background of the studies plus a collection of indicative content from over 400 heritage studies was traversed. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 2057

Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 2057 Identifier Beacon Formerly unknown Marine Pde Blessington St Wordsworth St Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO167 Address Marine Parade Category Public ST. KILDA Constructed unknown Designer unknown Amendment C 29 Comment Significance (Mapped as a Significant heritage property.) This visually distinctive structure is of significance primarily as a scenic element which contributes to the maritime character of the Foreshore area. Primary Source Robert Peck von Hartel Trethowan, St Kilda 20th century Architectural Study Vol. 3, 1992 Other Studies Description Beacon History see Description Thematic Context unknown Recommendations A Ward, Port Phillip Heritage Review, 1998 recommended inclusions: National Estate Register Schedule to the Heritage Overlay Table in the City of Port Phillip Planning Scheme References unknown Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 2048 Identifier "Arden" Formerly Residence Cavell St Spencer St Marine Pde Shakespeare Gr Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO298 Address 1-2 Marine Parade Category Residential:row ST. KILDA Constructed 1880's-1934 Designer unknown; (1924) H.V. Gillespie Amendment C 29 Comment Significance (Mapped as a Significant heritage property.) "Arden" at nos. 1-2 Marine Parade, St Kilda, was built in 1881-83 as a two storeyed terraced pair but presumably altered to form the present Arden Flats in 1934. It is historically and aesthetically significant. It is historically significant (Criterion A) for its capacity to demonstrate two important phases in the evolution of St Kilda, the first being the period of late Victorian expansion and the second being the Inter War years during which St Kilda emerged as a pre-eminent location for apartments. -

Special Descriptions Listing

Office of Surveyor‐ General Victoria Page | 1 of 6 SPECIAL DESCRIPTIONS LISTING Code VOTS Database Name / Plan Presentation VicMap Database Name Note: Parish code to be listed on OP plans only (not on Title Plans) 2007A Alberton, At : Parish of Alberton East COUNTY: BULN BULN PARISH: ALBERTON EAST ALBERTON, AT (ALBERTON EAST)) AT ALBERTON (2007A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2042A Raymond Island, At : Parish of Bairnsdale COUNTY: TANJIL PARISH: BAIRNSDALE RAYMOND ISLAND, AT (BAIRNSDALE) AT RAYMOND ISLAND (2042A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2209A Hawthorn, At : Parish of Boroondara COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: BOROONDARA HAWTHORN, AT (BOROONDARA) CITY OF HAWTHORN (2209A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2287A Scotchmans, At : Parish of Buninyong COUNTY: GRANT PARISH: BUNINYONG SCOTCHMANS, AT (BUNINYONG) AT SCOTCHMANS (2287A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2478A Footscray, City of : Parish of Cut‐paw‐Paw COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: CUT‐PAW‐PAW FOOTSCRAY, CITY (CUT‐PAW‐PAW) CITY OF FOOTSCRAY (2478A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2478B Footscray, City of : At Yarraville : Parish of Cut‐Paw‐Paw COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: CUT‐PAW‐PAW FOOTS CITY, AT Y/VILLE (CUT‐PAW‐PAW) AT YARRAVILLE CITY OF FOOTSCRAY (2478B) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2478C West Footscray, At : Parish of Cut‐Paw‐Paw COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: CUT‐PAW‐PAW W/FOOTSCRAY, AT (CUT‐PAW‐PAW) AT WEST FOOTSCRAY (2478C) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2478D Yarraville, At : Parish of Cut‐Paw‐Paw COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: CUT‐PAW‐PAW YARRAVILLE, AT (CUT‐PAW‐PAW) AT YARRAVILLE (2478D) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: J:\lr\CSA\CSA Procedures\Crown Description\Special Descriptions\Special Descriptions_OSGV Listing 18‐05‐2018.docx Office of Surveyor‐ General Victoria Page | 2 of 6 Code VOTS Database Name / Plan Presentation VicMap Database Name Note: Parish code to be listed on OP plans only (not on Title Plans) 2541A Essendon, At : Parish of Doutta Galla COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: DOUTTA GALLA ESSENDON, AT (DOUTTA GALLA) AT ESSENDON (2541A) SECTION: CROWN ALLOTMENT: 2541B Essendon, City of : Parish of Doutta Galla COUNTY: BOURKE PARISH: DOUTTA GALLA ESS. -

Citation Report

Citation No: City of Port Phillip Heritage Review 2164 Identifier Restaurant Formerly unknown Nelson St Punt Rd Wellington St Heritage Precinct Overlay None Heritage Overlay(s) HO232 Address 14 Punt Rd Category Commercial WINDSOR Constructed 1905 Designer Amendment C 29 Comment Significance (Mapped as a Significant heritage property.) The former shops and residential building at 14-15 Punt Road, Windsor was built in 1905 for C. Peacoulakes. It is aesthetically important (Criterion E). This importance rests on its unusual façade treament consisting of suspended pilasters capped by figures of cherubs and other ornamentation. The building's cultural value hinges also on its prominent position at St. Kilda Junction and on its capacity to recall a time when this intersection was an important civic space. Primary Source Andrew Ward, City of Port Phillip Heritage Review, 1998 Other Studies Description A three storeyed former retail and residential building distinguished by its romantic arcaded façade treatment with faceted suspended piers surmounted by cherubs at first floor level. The windows are round arched with cast cement shell ends whilst the upper level is more severe, having round arched windows, a simple cornice and the date "1905" in raised cement to the pediment which may have been defaced by a surmounting advertising sign. The side elevation is of utilitarian character in overpainted face brickwork. Condition: Sound. Integrity: Medium, Ground level façade defaced. History At the turn of the century there were two shops each described as “brick and wood, two rooms” on the south east corner of Hoddle Street (Punt Road) and Nelson Street which were owned by Albert Burgess.