A Look at Renaissance Ferrara Charles M. Rosenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Nostra Storia

I.R. 1976 2006 ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI ASSISTENZA E DI PATRONATO PER L’ARTIGIANATO SEDE TERRITORIALE DI UDINE Bollettino degli Organi direttivi di Associazione Sindacale Bollettino degli Organi direttivi Periodico quindicinale - Poste Italiane s.p.a. Spedizione in Abbonamento in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1, comma Postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. D.C.B. Udine 1976 ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI ASSISTENZA E DI PATRONATO PER L’ARTIGIANATO 2006 ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI ASSISTENZA E DI PATRONATO PER L’ARTIGIANATO Confartigianato, a livello nazionale e Cos’è provinciale, collabora nella formulazione dei L’INAPA è l’ente di patronato della provvedimenti legislativi e nella proposizione di Confartigianato ed è presente anche in adeguati correttivi alle procedure operative provincia di Udine con una Sede centrale ed messe in atto dagli enti previdenziali e alcune Sedi zonali. Offre gratuitamente ogni tipo assistenziali. di assistenza e tutela sociale nel rapporto tra SERVIZIO MEDICO LEGALE utente e enti assistenziali e previdenziali. Il suo Per le consulenze mediche compito è infatti quello di risolvere i problemi l’INAPA si avvale dell’opera di medici specialisti che i cittadini quotidianamente incontrano nei ed offre visite ambulatoriali gratuite. rapporti con la Previdenza Sociale (INPS), L’INAPA offre anche assistenza legale in caso di l’INAIL, le Aziende Sanitarie e tutti gli altri enti proposizioni di azioni giudiziarie nei confronti pubblici che operano in questo campo. degli enti previdenziali e assistenziali. Tali servizi sono stati istituiti a salvaguardia dei Cosa fa diritti degli assistiti, quando questi non sono stati riconosciuti dagli Istituti Assicuratori. L’INAPA è in grado di svolgere ogni pratica amministrativa di pensione, infortuni, malattie Rientrano inoltre tra i servizi ottenibili: professionali in modo da mettere l’utente in • domande per pensioni di vecchiaia, condizione di affrontare questi adempimenti anzianità, invalidità; con serenità e la garanzia di un supporto • domande di pensioni di “reversibilità” e competente e tempestivo. -

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Architecture As Performance in Seventeenth-Century Europe: Court Ritual in Modena, Rome, and Paris by Alice Jarrard John E

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks Art: Faculty Publications Art Winter 2004 Reviewed Work(s): Architecture as Performance in Seventeenth-Century Europe: Court Ritual in Modena, Rome, and Paris by Alice Jarrard John E. Moore Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/art_facpubs Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Moore, John E., "Reviewed Work(s): Architecture as Performance in Seventeenth-Century Europe: Court Ritual in Modena, Rome, and Paris by Alice Jarrard" (2004). Art: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/art_facpubs/9 This Book Review has been accepted for inclusion in Art: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] Review Reviewed Work(s): Architecture as Performance in Seventeenth-Century Europe: Court Ritual in Modena, Rome, and Paris by Alice Jarrard Review by: John E. Moore Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Winter, 2004), pp. 1398-1399 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4143727 Accessed: 09-07-2018 15:52 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. -

Journal Pre-Proof

Journal Pre-proof From Historical Seismology to seismogenic source models, 20 years on: Excerpts from the Italian experience Gianluca Valensise, Paola Vannoli, Pierfrancesco Burrato, Umberto Fracassi PII: S0040-1951(19)30296-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2019.228189 Reference: TECTO 228189 To appear in: Tectonophysics Received date: 1 April 2019 Revised date: 20 July 2019 Accepted date: 5 September 2019 Please cite this article as: G. Valensise, P. Vannoli, P. Burrato, et al., From Historical Seismology to seismogenic source models, 20 years on: Excerpts from the Italian experience, Tectonophysics(2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2019.228189 This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. © 2019 Published by Elsevier. Journal Pre-proof From Historical Seismology to seismogenic source models, 20 years on: excerpts from the Italian experience Gianluca Valensise, Paola Vannoli, Pierfrancesco Burrato & Umberto Fracassi Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Rome, Italy Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Why Historical Seismology 1.2. A brief history of Historical Seismology 1.3. Representing and exploiting Historical Seismology data 2. -

André Derain Stoppenbach & Delestre

ANDR É DERAIN ANDRÉ DERAIN STOPPENBACH & DELESTRE 17 Ryder Street St James’s London SW1Y 6PY www.artfrancais.com t. 020 7930 9304 email. [email protected] ANDRÉ DERAIN 1880 – 1954 FROM FAUVISM TO CLASSICISM January 24 – February 21, 2020 WHEN THE FAUVES... SOME MEMORIES BY ANDRÉ DERAIN At the end of July 1895, carrying a drawing prize and the first prize for natural science, I left Chaptal College with no regrets, leaving behind the reputation of a bad student, lazy and disorderly. Having been a brilliant pupil of the Fathers of the Holy Cross, I had never got used to lay education. The teachers, the caretakers, the students all left me with memories which remained more bitter than the worst moments of my military service. The son of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was in my class. His mother, a very modest and retiring lady in black, waited for him at the end of the day. I had another friend in that sinister place, Linaret. We were the favourites of M. Milhaud, the drawing master, who considered each of us as good as the other. We used to mark our classmates’s drawings and stayed behind a few minutes in the drawing class to put away the casts and the easels. This brought us together in a stronger friendship than students normally enjoy at that sort of school. I left Chaptal and went into an establishment which, by hasty and rarely effective methods, prepared students for the great technical colleges. It was an odd class there, a lot of colonials and architects. -

Animal Life in Italian Painting

UC-NRLF III' m\ B 3 S7M 7bS THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTED BY PROF. CHARLES A. KOFOID AND MRS. PRUDENCE W. KOFOID ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING THt VISION OF ST EUSTACE Naiionai. GaM-KUV ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING BY WILLIAM NORTON HOWE, M.A. LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & COMPANY, LTD. 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE 1912 [All rights reserved] Printed by Ballantvne, Hanson 6* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh / VX-/ e3/^ H67 To ©. H. PREFACE I OWE to Mr. Bernhard Berenson the suggestion which led me to make the notes which are the foundation of this book. In the chapter on the Rudiments of Connoisseurship in the second series of his Study and Criticism of Italian Art, after speaking of the characteristic features in the painting of human beings by which authorship " may be determined, he says : We turn to the animals that the painters, of the Renaissance habitually intro- duced into pictures, the horse, the ox, the ass, and more rarely birds. They need not long detain us, because in questions of detail all that we have found to apply to the human figure can easily be made to apply by the reader to the various animals. I must, however, remind him that animals were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. Vasari, for instance, gets into a fury of contempt when describing Sodoma's devotion to pet birds and horses." Having from my schooldays been accustomed to keep animals and birds, to sketch them and to look vii ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING for them in painting, I had a general recollection which would not quite square with the statement that they were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. -

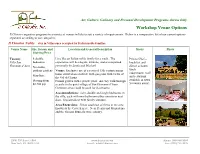

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Tesi GALVANI

Università degli Studi di Ferrara DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Scienze e Tecnologie per l’Archeologia e i Beni Culturali CICLO XXII COORDINATORE Prof. Carlo Peretto La rappresentazione del potere nell’età di Borso d’Este: ”imprese” e simboli alla Corte di Ferrara Settore Scientifico Disciplinare L-ART/02 Dottorando Tutore Dott. Irene Galvani Prof. Ranieri Varese Anni 2007/2009 Corso di Dottorato in convenzione con 0 Indice Indice: p. 1 Introduzione: Arte e potere nel panorama ferrarese: la corte si rappresenta attraverso le “imprese” p. 5 Capitolo 1: Le “imprese” al servizio del potere: esempi dalla tradizione estense p. 8 1.1: Le divise araldiche dall’antichità al ‘500: espressioni di un potere individuale p. 8 1.2: “Imprese” e divise alla corte di Ferrara: una breve introduzione p. 11 1.2.1: Leonello, il Marchese umanista: insegne d’amore e di cultura all’ombra della letteratura francese p. 12 1.2.2: Borso, il primo Duca e le sue insegne p. 18 1.2.3: Ercole I, un diamante e un codice scomparso p. 24 1.2.4: La granata del primo Alfonso p. 26 1.2.5: Ercole II ed Alfonso II: l’importanza del motto p. 27 Capitolo 2: La trattatistica sulle “imprese” in Italia dal XVI al XX secolo p. 29 2.1: I primordi. Da Bartolo da Sassoferrato a Paolo Giovio p. 29 2.2: Riflessioni post-gioviane: Girolamo Ruscelli, Bartolomeo Taegio, Luca Contile ed altri autori p. 35 2.3: Verso il ‘600. Torquato Tasso, Tommaso Garzoni e Andrea Chiocco p. 44 2.4: Ritrovata fortuna degli studi araldici nella prima metà del XX secolo p. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Musei E Monumenti

Musei e Monumenti 1 MUSEI Indice Casa di Ludovico Ariosto E MONUMENTI Casa di Ludovico Ariosto 3 Via Ariosto 67. Tel. 0532 244949 Casa Romei Parva , sed apta mihi, sed nulli obnoxia, sed non sordida, par- Castello Estense 4 ta meo, sed tamen aere domus (la casa è piccola, ma adatta Cattedrale 6 a me, pulita, non gravata da canoni e acquistata solo con UFFICI INFORMAZIONI TURISTICHE Chiesa di San Cristoforo alla Certosa FERRARA il mio denaro): questa è l’iscrizione sulla facciata della casa Castello Estense Chiesa di San Domenico 8 Tel: 0532 209370 Chiesa di Santa Maria in Vado dove Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533) trascorse gli ultimi anni Fax 0532 212266 della sua vita dedicandosi alla terza e definitiva edizione Chiesa di San Francesco Piazza Municipale 11 Chiesa di San Giorgio 10 dell’Orlando Furioso. L’abitazione, realizzata probabilmen- Tel. 0532 419474 Fax 0532 419488 Chiesa del Gesù te su disegno di Girolamo da Carpi, presenta una facciata Chiesa di San Paolo ARGENTA semplice ma elegante in mattoni a vista. Via Matteotti, 24/b Monastero del Corpus Domini 13 Tel. 800 014669 Al primo piano è sistemato un piccolo museo dedicato al Fax 0532 330215 Monastero di Sant’Antonio in Polesine Museo Archeologico Nazionale 14 grande poeta. Vi sono conservati il calco del suo calamaio, CENTO la sua sedia e molte medaglie che lo rappresentano, fra Via Guercino, 41 Museo dell’Architettura Tel. 051 6843334 Museo dell’Illustrazione cui quella rinvenuta nella sua tomba nel 1801. Fax 051 6843309 Museo di Storia Naturale Nel piccolo corridoio centrale è conservata la preziosa CODIGORO Abbazia di Pomposa Museo della Cattedrale 16 edizione dell’Orlando Furioso illustrata da Gustave Doré S.S. -

Dreamitaly0709:Layout 1

INSIDE: The Artistic Village of Dozza 3 Private Guides in Ravenna 5 Bicycling Through Ferrara 6 Where to Stay in Bologna 8 Giorgio Benni Giorgio giasco, flickr.com giasco, Basilica di San Vitale MAMbo SPECIAL REPORT: EMILIA-ROMAGNA Bologna: dream of City of Art ith its appetite for art, Bologna’s ® Wcontributions to the good life are more than gustatory. Though known as the “Red City” for its architecture and politics, I found a brilliant palette of museums, galleries, churches and markets, with mouth-watering visuals for every taste. ITALYVolume 8, Issue 6 www.dreamofitaly.com July/August 2009 City Museums For a splash of Ravcnna’s Ravishing Mosaics 14th-century sculp- ture start at the fter 15 centuries, Ravenna’s lumi- across the region of Emilia-Romagna. Fontana del Nettuno A nous mosaics still shine with the With only a day to explore, I’m grate- in Piazza Maggiore. golden brilliance of the empires that ful that local guide Verdiana Conti Gianbologna’s endowed them. These shimmering Baioni promises to weave art and bronze god — Fontana Nettuno sacred images reveal both familiar and history into every step. locals call him “the giant” — shares the unexpected chapters in Italian history water with dolphins, mermaids and while affirming an artistic climate that We meet at San Apollinaire Nuovo on cherubs. Close by, Palazzo Comunale’s thrives today. Via di Roma. A soaring upper floors contain the Collezioni basilica, its narrow side Comunale d’Arte, which includes opu- Ravenna attracted con- aisles open to a broad lent period rooms and works from the querors from the north nave where three tiers 14th through 19th centuries. -

Ferrara Di Ferrara

PROVINCIA COMUNE DI FERRARA DI FERRARA Visit Ferraraand its province United Nations Ferrara, City of Educational, Scientific and the Renaissance Cultural Organization and its Po Delta Parco Urbano G. Bassani Via R. Bacchelli A short history 2 Viale Orlando Furioso Living the city 3 A year of events CIMITERO The bicycle, queen of the roads DELLA CERTOSA Shopping and markets Cuisine Via Arianuova Viale Po Corso Ercole I d’Este ITINERARIES IN TOWN 6 CIMITERO EBRAICO THE MEDIAEVAL Parco Corso Porta Po CENTRE Via Ariosto Massari Piazzale C.so B. Rossetti Via Borso Stazione Via d.Corso Vigne Porta Mare ITINERARIES IN TOWN 20 Viale Cavour THE RENAISSANCE ADDITION Corso Ercole I d’Este Via Garibaldi ITINERARIES IN TOWN 32 RENAISSANCE Corso Giovecca RESIDENCES Piazza AND CHURCHES Trento e Trieste V. Mazzini ITINERARIES IN TOWN 40 Parco Darsena di San Paolo Pareschi WHERE THE RIVER Piazza Travaglio ONCE FLOWED Punta della ITINERARIES IN TOWN 46 Giovecca THE WALLS Via Cammello Po di Volano Via XX Settembre Via Bologna Porta VISIT THE PROVINCE 50 San Pietro Useful information 69 Chiesa di San Giorgio READER’S GUIDE Route indications Along with the Pedestrian Roadsigns sited in the Historic Centre, this booklet will guide the visitor through the most important areas of the The “MUSEO DI QUALITÀ“ city. is recognised by the Regional Emilia-Romagna The five themed routes are identified with different colour schemes. “Istituto per i Beni Artistici Culturali e Naturali” Please, check the opening hours and temporary closings on the The starting point for all these routes is the Tourist Information official Museums and Monuments schedule distributed by Office at the Estense Castle.