A Primer on Prior Learning Assessments and Competency-Based Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board Letter for February 7, 2018 Meeting

LOS ANGELES COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT EAST CITY HARBOR MISSION PIERCE SOUTHWEST TRADE TECHNICAL VALLEY WEST OFFICE OF THE CHANCELLOR TO: Members of the Board of Trustees FROM: Dr. Francisco Rodriguez, Chancellor DATE: February 2, 2018 SUBJECT: BOARD LETTER FOR FEBRUARY 7, 2018 MEETING Board Meeting Location Next week’s Board meeting will be held at the Los Angeles Trade-Technical College. The meeting times and locations are as follows: Meetings Time Location Convene for First Public Session 2:00 p.m. – 4:45 p.m. Aspen Hall 101 Break 4:45 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. Convene for Closed Session 5:00 p.m. – 7:00 p.m. Aspen Hall 113 Reconvene for Second Public Session Immediately Following Aspen Hall 113 Closed Session Parking Parking for Board Members and Chancellor will be located in the Pegasus Parking Lot. A campus map has been included for your convenience. Please be aware that there will be a meeting of the Committee of the Whole. One presentation will be made: Update on the LACCD Undocumented Student/DACA Included in this letter is explanatory information related to agenda items: Under the Chancellor’s Report, Cheryl Broom, President, Interact Communications, will present: Strategic Enrollment Management Campaign for Spring 2018 Enrollment Growth. (Refer to Attachment A) 770 WILSHIRE BOULEVARD, LOS ANGELES, CA 90017, (213) 891-2201 FAX (213) 891-2304 Board Letter – February 7, 2018 Page 2 of 2 Confidential Matters The attached correspondence is confidential and should not be shared with other persons. Office of General Counsel o Enclosed for your review is the District-related litigation report. -

Student Academic Outcomes Report

Student Academic Outcomes Report Fall 2017 BOARD OF SCHOOL DIRECTORS Mary D. Birks, President William J. Moorhead, Vice President Hugh L. Beal William L. Cooper Lawrence M. Lebowitz Sarah L. Olbrich Daniel L. Remely Michael J. Riemer Stephen J. Strotmeyer Thomas P. Peterson, Solicitor MT. LEBANON SCHOOL DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION Timothy J. Steinhauer, Ed.D. – Superintendent of Schools Marybeth D. Irvin, Ph.D. – Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Education Ronald P. Davis, Ed.D. – Assistant Superintendent of Secondary Education BUILDING PRINCIPALS Jason Ramsey – Foster Elementary School Nicole Giehll – Hoover Elementary School Michelle Murray, Ed.D. – Howe Elementary School Sarah Shaw, Ed.D. – Jefferson Elementary School TBA – Markham Elementary School Ron Kitsko – Lincoln Elementary School Melissa Nelson – Washington Elementary School Kelly Szesterniak – Jefferson Middle School Christopher Wolfson – Mellon Middle School Brian McFeeley – High School TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 6 Mission Statement ......................................................................................................... 10 The Graduate • Post Graduate Activities ..................................................................................... 11 • Analysis of College Attendance by Competitiveness ......................................... -

National Accredited School List Provided by US News 2017-2018

National Accredited School List Provided by US News 2017-2018 Name of School City ALABAMA Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University Normal Alabama State University Montgomery Amridge University Montgomery Athens State University Athens Auburn University Auburn Auburn University– Montgomery Montgomery Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham Concordia College Selma Faulkner University Montgomery Huntingdon College Montgomery Jacksonville State University Jacksonville Judson College Marion Miles College Birmingham Oakwood University Huntsville Samford University Birmingham Spring Hill College Mobile Stillman College Tuscaloosa Talladega College Talladega Troy University Troy Tuskegee University Tuskegee University of Alabama Tuscaloosa University of Alabama-Birmingham Birmingham University of Alabama–Huntsville Huntsville University of Mobile Mobile University of Montevallo Montevallo University of North Alabama Florence University of South Alabama Mobile University of West Alabama Livingston ALASKA Alaska Pacific University Anchorage University of Alaska–Anchorage Anchorage University of Alaska–Fairbanks Fairbanks University of Alaska–Southeast Juneau ARIZONA American Indian College Phoenix Arizona Christian University Phoenix Arizona State University–Tempe Tempe Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture Scottsdale Grand Canyon University Phoenix Northcentral University Prescott Valley Northern Arizona University Flagstaff Prescott College Prescott National Accredited School List Provided by US News 2017-2018 Name of School City Southwest -

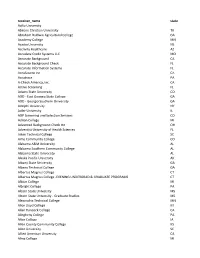

Receiver Name State Aalto University Abilene Christian University TX Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College GA Academy College MN

receiver_name state Aalto University Abilene Christian University TX Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College GA Academy College MN Acadia University NS Acclivity Healthcare AZ Accudata Credit Systems LLC MO Accurate Background CA Accurate Background Check FL Accurate Information Systems FL AccuSource Inc CA Accutrace PA A-Check America, Inc. CA Active Screening FL Adams State University CO ADD - East Georgia State College GA ADD - Georgia Southern University GA Adelphi University NY Adler University IL ADP Screening and Selection Services CO Adrian College MI Advanced Background Check Inc OH Adventist University of Health Sciences FL Aiken Technical College SC Aims Community College CO Alabama A&M University AL Alabama Southern Community College AL Alabama State University AL Alaska Pacific University AK Albany State University GA Albany Technical College GA Albertus Magnus College CT Albertus Magnus College -EVENING UNDERGRAD & GRADUATE PROGRAMS CT Albion College MI Albright College PA Alcorn State University MS Alcorn State University - Graduate Studies MS Alexandria Technical College MN Alice Lloyd College KY Allan Hancock College CA Allegheny College PA Allen College IA Allen County Community College KS Allen University SC Allied American University CA Alma College MI Alpena Community College MI Alvernia University PA Alverno College WI Alvin Community College TX Amberton University TX American Academy of Dramatic Arts - All Campuses CA American Academy of Nurse Practitioners TX American Association of Critical-Care Nurses CA American Association of Medical Assistants IL American Career College - Los Angeles CA American Career College - Ontario CA American College for Medical Careers FL American College of Healthcare CA American College of Healthcare Sciences OR American Institue FL American Institute of Beauty, Inc. -

Triton High School P Reparation for Caree Rs, College and Communit Y C O N N E C T E D L E a R N I N G • R E L E V a N T S K I L L S • Respectful Environme Nt

TRITON HIGH SCHOOL P REPARATION FOR CAREE RS, COLLEGE AND COMMUNIT Y C O N N E C T E D L E A R N I N G • R E L E V A N T S K I L L S • RESPECTFUL ENVIRONME NT 112 Elm Street, Byfield, Massachusetts 01922 – Telephone 978-462-9458 – Fax 978-463-5851 Counselors: Kathryn E. Dawe, Principal Erik Champy Scott Brennan, Asst. Principal [email protected] Kristen E. Lazarro, Asst. Principal Profile - 201 4 Karen Christian Sean McInnis, Athletic Director [email protected] Sheila K. Deam, Director of Guidance Meghan Ober CEEB Code # 221 842 [email protected] Jessica Hoyt, Guidance Registrar [email protected] LOCATION – The Triton Regional School District serves the Massachusetts coastal towns of Newbury, Rowley and Salisbury. Located in the northeast corner of the state, these three communities provide a distinct population of students to the school district. With all three rural towns dating back to the 1630’s, the area is rich in historical traditions and attractions which add to the academic experience of our students. The student population for the Triton District in 2013-2014 was 2,800 with 94% white, and 6% African American, Hispanic, Native American, or Asian American. The Triton High School teaching staff is a dedicated group of educators, of whom 81% hold advanced degrees. 100% are licensed and 100% of the teachers in the core academic subjects are Highly Qualified under NCLB regulations. The average teacher/student ratio is 13:1. TYPE – Triton High School is a four-year comprehensive high school with an enrollment of approximately 748. -

Granite State Arts Academy a Charter School

Granite State Arts Academy a charter school Granite State Arts Academy 16 Route 111 Building 4, Derry, NH 03038 Phone: 603.912.4944 Email: [email protected] Don Erdbrink Chairman-Board of Trustees [email protected] 1 Table of Contents a. Educational mission 3 b. Governance and organizational structure and plan 3 c. Methods by which trustees and their terms are determined 4 d. General description and location of facilities 5 e. Pupil demographics 6 f. Curriculum 6 g. Academic goals 7 h. Achievement and assessments 12 i. High school graduation requirements 13 j. Staffing overview 14 k. Personnel compensation plans 14 l. Pupil transportation plan 15 m. Statement of assurances related to non-discrimination 15 n. Special Education coordination method 15 o. Admission procedures 16 p. Philosophy of pupil governance and discipline 17 q. Administering fiscal accounts and reporting 18 r. School calendar arrangement 19 s. Evidence of adequate insurance coverage 19 t. Consultants and friends of the charter 19 u. Philosophy of parent involvement 20 v. Information dissemination 20 w. A global hold-harmless clause 20 x. Severability provisions and statement of assurance 21 y. Provision for dissolution of the charter 21 aa. Information related to conversion of a public school 21 bb. Cessation of the school 22 cc. Proposed contract with local schools 22 dd. Proposed accountability plan 22 Appendix A: Founding Members’ biographies Appendix B: School Day Schedule 2 (a) Educational mission Granite State Arts Academy (hereafter referred to as “GSAA,” or “the School”) nurtures creative thinkers, active citizens, and independent learners with a curriculum that integrates the arts and academics. -

List of For-Profit Universities and Colleges

List of for-profit universities and colleges This is a list of for-profit institutions of higher education. Contents In the United States Closed Outside the United States Distance education (online) See also References In the United States Academy of Art University – San Francisco, California American Career College – Los Angeles, California American College of Education – online American InterContinental University – more than 90% online, a subsidiary of Career Education Corporation American Military University – online, a division of American Public University System American National University – distance education and multiple locations in Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and West Virginia; not to be confused with American University American Public University – online American Sentinel University – online Antilles College of Health – Puerto Rico Antonelli College – multiple locations Arizona Summit Law School – a subsidiary of InfiLaw System ASA College – campuses in Brooklyn, midtown Manhattan, and Miami Ashford University – Clinton, Iowa (campus closed in 2016), a subsidiary of Bridgepoint Education, includes Forbes School of Business Aspen University – Denver, Colorado Atenas College – multiple locations, Puerto Rico Bay State College – Boston, Massachusetts Beckfield College – a subsidiary of Quad Partners Berkeley College – New York and New Jersey; not to be confused with University of California, Berkeley, Berklee School of Music or the Berkeley College at Yale University Blair College – Colorado Springs, Colorado - Now Everest -

Fairtest the National Center for Fair & Open Testing

FairTest The National Center for Fair & Open Testing 870+ Accredited Colleges and Universities That Do Not Use ACT/SAT Scores to Admit Substantial Numbers of Students Into Bachelor-Degree Programs Current as of Fall 2016 This list includes institutions that are "test optional," "test flexible" or otherwise de-emphasize the use of standardized tests by making admissions decisions -- without using ACT or SAT scores -- for all or many applicants who recently graduated from U.S. high schools. As the endnotes indicate, some schools exempt students who meet minimum grade-point average or class rank criteria; others require SAT or ACT scores but use them only for placement purposes. Please check with the school's admissions office for details Sources: Barron's Profiles of American Colleges 2015; College Board 2017 College Handbook; U.S. News & World Report College Guide 2016; admissions office websites; news reports; and email communications. A American Sentinel University, Online Academy College3, Minneapolis, MN American University, Washington, DC Academy of Art University, San Francisco, CA Amridge University, Online Academy of Couture Art, West Hollywood, CA Andrew University, Online Adventist University of Health Sciences, Orlando, FL1 Angelo State University3, Angelo, TX Agnes Scott College, Decatur, GA Anna Maria College, Paxton, MA Albright College, Reading, PA Antioch University - Midwest, Yellow Springs, OH Alcorn State University1, 3, Alcorn, MS Apex School of Theology, Durham, NC Allegheny College, Meadville, PA Argosy University, -

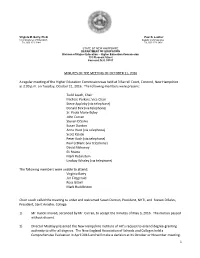

1 MINUTES of the MEETING of OCTOBER 11, 2016 a Regular

Virginia M. Barry, Ph.D. Paul K. Leather Commissioner of Education Deputy Commissioner Tel. 603-271-3144 Tel. 603-271-3801 STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Division of Higher Education – Higher Education Commission 101 Pleasant Street Concord, N.H. 03301 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF OCTOBER 11, 2016 A regular meeting of the Higher Education Commission was held at 3 Barrell Court, Concord, New Hampshire at 2:00 p.m. on Tuesday, October 11, 2016. The following members were present: Todd Leach, Chair Michele Perkins, Vice Chair Steve Appleby (via telephone) Donald Birx (via telephone) Sr. Paula Marie Buley John Curran Steven DiSalvo Susan Dunton Anne Huot (via telephone) Scott Kalicki Peter Koch (via telephone) Paul LeBlanc (via telephone) David Mahoney Eli Rivera Mark Rubinstein Lindsay Whaley (via telephone) The following members were unable to attend: Virginia Barry Jim Fitzgerald Ross Gittell Mark Huddleston Chair Leach called the meeting to order and welcomed Susan Dunton, President, NHTI, and Steven DiSalvo, President, Saint Anselm, College. 1) Mr. Kalicki moved, seconded by Mr. Curran, to accept the minutes of May 3, 2016. The motion passed without dissent. 2) Director MacKay presented the New Hampshire Institute of Art’s request to extend degree-granting authority to offer all degrees. The New England Association of Schools and Colleges held a Comprehensive Evaluation in April 2016 and will make a decision at its October or November meeting. 1 With the New Hampshire Institute of Art’s approval expiring December 31, 2016, it was recommended that the Commission vote to extend degree-granting authority until June 30, 2017. -

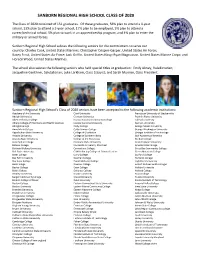

Class of 2020 Statistics

SANBORN REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL CLASS OF 2020 The Class of 2020 consisted of 151 graduates. Of these graduates, 56% plan to attend a 4-year school, 13% plan to attend a 2-year school, 17% plan to be employed, 5% plan to attend a career/technical school, 5% plan to work in an apprenticeship program, and 4% plan to enter the military or armed forces. Sanborn Regional High School salutes the following seniors for the commitment to serve our country: Charles Cook, United States Marines; Christopher Crispim-Gasper, United States Air Force; Kacey Frost, United States Air Force; Jack Griffin, United States Navy; Ryan Magnusson, United States Marine Corps; and Horace Wood, United States Marines. The school also salutes the following seniors who held special titles at graduation: Emily Abney, Valedictorian; Jacqueline Genthner, Salutatorian; Luke Larkham, Class Essayist; and Sarah Munroe, Class President. Sanborn Regional High School’s Class of 2020 seniors have been accepted to the following academic institutions: Academy of Art University Clark University Franciscan University of Steubenville Adelphi University Clarkson University Franklin Pierce University Aiken Technical College Coastal Carolina Community College Full Sail University Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Coastal Carolina University Gannon University Albright College Colby College George Mason University Anna Maria College Colby-Sawyer College George Washington University Appalachian State University College of Charleston Georgia Institute of Technology Arcadia University -

2016-2017 University College Academic Catalog

Southern New Hampshire University University College 2016-2017 Catalog Published June 20, 2016 2016-2017 University College Catalog Southern New Hampshire University Welcome to Southern New Hampshire University Message from the President It gives me great pleasure to present to you the Southern New Hampshire University catalogs. A university catalog offers a comprehensive overview of the variety of programs and classes offered both on campus and online. These catalogs contain information about our history and mission, our services and outreach, our facilities and the many opportunities we provide students for meeting their life and career goals. It's certainly an exciting time to be a student at SNHU. President Obama has praised us for finding new innovative pathways to a degree. Fast Company has named us the 12th most innovative organization in the world in its World's 50 Most Innovative Companies. We ranked with such heavy-hitters as Apple, Google and HBO and were listed ahead of such industry giants as the National Football League, Starbucks and LinkedIn. We achieved such accolades on the basis of our innovative pathways to a degree and our core mission of providing access. Our campus-based Degree-in-Three program, which uses a competency-based model to reduce time to graduation and the cost of a degree by 25 percent. Students studying with us online are part of the second largest non-profit program in the country. SNHU continues to give you more options to complete your degree than almost any other institution. You can blend traditional on-campus courses with wholly online courses or take a mix in one of our hybrid courses. -

Corin Brennan's Resume

Salem, NH 603-401-1635 [email protected] CorinBrennan.com PROFILE Detail-oriented designer in search of a position in a creative environment that allows me to utilize my abilities and skills in art, developed through my education and experience. Art and creativity are an important part of my world. I love to create and mold an idea into something appealing, desirable, and functional. It is important to create a design that engages its intended audience and delivers a unique experience. SKILLS • Adobe Photoshop CS6 • Microsoft Office Suite • Adobe Illustrator CS6 • Joomla CMS (novice) • Adobe InDesign CS6 • XHTML/CSS (novice) • Adobe Dreamweaver CS6 • Mac and PC platforms EDUCATION • Bachelor of Arts: Graphic Design and Media Arts Southern New Hampshire University - Online 2014 - Currently Attending. Current GPA: 4.00 • Associates of Science: Business Administration Mount Washington College - Manchester, New Hampshire 2011-2012, 2013-2014. GPA: 4.00 • Associates of Science: Graphic Design Mount Washington College - Manchester, New Hampshire 2012 - 2013. GPA: 4.00 • Associates of Science: Veterinary Technology Great Bay Community College - Stratham, New Hampshire 2005 – 2007. GPA: 3.66 EXPERIENCE Granite State Carriage Association • Maintain association’s website including updating calendars www.granitestatecarriage.org and organization documents, creating forms, and maintaining Media Technical Advisor site users. 2013-present • Maintain social media pages and assist with digital publicity. Johnson Veterinary Hospital • Demonstrate proficiency in all aspects of animal medical care: Lawrence, MA taking patient medical histories and vital signs, performing Head Veterinary Technician venipuncture, catheterization, radiographs, various 2009-present diagnostic and laboratory procedures, and surgical preparation, monitoring and assistance. • Leadership and supervision of other technicians and assistants, responsible for interviews, hiring and training.