A M D G Beaumont Union Review Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aston Martin Vantage AMR Le Mans 24 H 2021 TF Sports Original 25 X 64 Cm Ben Keating 790 Euros Dylan Pereira Felipe Fraga Copyright Uli Ehret

#984 Aston Martin Vantage AMR Le Mans 24 H 2021 TF Sports Original 25 x 64 cm Ben Keating 790 Euros Dylan Pereira Felipe Fraga copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehretcopyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret „XS“ Framed Paintings - 15 x 30 cm Colour: silver frame Colour: black frame Order code: 0984_XS_S Order code: 0984_XS_B Price: 65,- Euro Price: 65,- Euro (incl. shipping EU/UK) (incl. shipping EU/UK) Limited edition prints framed behind glass. 1 of only 100 reproductions. Double mount in two colours. Price includes framing and shipping to EU/UK. Delivery in 3 to 5 days. Worldwide shipping possible, please ask for quote. „XS-Plus“ Framed Paintings - 20 x 50 cm Colour: silver frame Colour: black frame Order code: 0984_XSPlus_S Order code: 0984_XSPlus_B Price: 99,- Euro Price: 99,- Euro (incl. shipping EU/UK) (incl. shipping EU/UK) Limited edition prints framed behind glass. 1 of only 100 reproductions. Double mount in two colours. Price includes framing and shipping to EU/UK. Delivery in 3 to 5 days. Worldwide shipping possible, please ask for quote. „XL“ Canvas, stretched on wooden chassis copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret copyright Uli Ehret Size: 30 x 100 cm Order code: 0984_XL_30100 Price: 229,- Euro (incl. shipping EU/UK) Size: 40 x 120 cm Order code: 0984_XL_40120 Price: 329,- Euro (incl. shipping EU/UK) Size: 50 x 180 cm Order code: 0984_XL_50180 Price: 479,- Euro (incl. shipping EU/UK) Size: 60 x 240 cm Order code: 0984_XL_60240 Price: 729,- Euro (incl. -

Slotmodel Slotcar

SLOTMODEL SLOTCAR CAMPEONATO SLOTMODEL CLASSICOS 60/70 - 1/32 REGULAMENTO ESPORTIVO 1 – CAMPEONATO Realizar-se-á em 8 (oito) etapas e dois descartes, com periodicidade quinzenal, às quartas-feiras, sendo a primeira prova em 13 de janeiro de 2021: SLOTMODEL SLOTCAR CALENDÁRIO CLASSIC 60-70 PROVA MÊS DATA P1 JANEIRO 13 P2 JANEIRO 27 P3 FEVEREIRO 10 P4 FEVEREIRO 24 P5 MARÇO 10 P6 MARÇO 24 P7 ABRIL 07 P8 ABRIL 21 2 - CARROS 2.1 Replicas 1/32 da categoria “CLASSICOS 60/70” de produção seriada. 2.2 Marcas sugeridas: NSR e Slot.it 2.3 Vide lista em Anexo A com carros “CLASSICOS 60/70” 3 – CORRIDA 3.1 Quantidade livre de pilotos; 3.2 Com a presença de mais de 8 pilotos presentes, a direção determinará a ocorrência de deck(s) ou segunda bateria. Por questões de horários, por padrão serão aceitas até duas baterias no dia, caso haja necessidade de mais baterias, deverá ocorrer no dia seguinte; 3.3 Com 10 pilotos ou mais serão 2 baterias dividindo os pilotos em dois grupos (A e B), de acordo com o ranking da tomada de tempo. 3.4 Os mais bem colocados na tomada de tempo ficarão no grupo A e o restante no grupo B. 3.5 A primeira bateria iniciará pelo grupo B e o grupo A ficará responsável pela recolocação dos carros, e na segunda bateria será respectivamente ao contrário. 4 – TIPO DE PROVA 4.1 A prova será equalizada individual; 4.2 Tempo de corte em 8,8 segundos por volta; 4.3 Controle automático pelo sistema de cronometragem; 5 – POLE 5.1 Será realizada a tomada de tempo dos competidores (qualificação) na fenda laranja, com duração de 1 minuto por piloto. -

Chill out Spa Liverpool Offers

Chill Out Spa Liverpool Offers Sawyer is infrangibly rockiest after Romanesque Bartholomew sprauchle his claddings heatedly. Keyless Luce grub invalidly. Equiprobable Thedric democratized preparatorily while Luciano always dehorns his acetals epistolizes flaringly, he engirdle so balletically. Spa packages in Liverpool we why the most creative and innovative spa packages available either the liverpool and Merseyside area. Please swap your emails match. Feedback remain a glue and important are therefore grateful to prevail where level can improve. It contains profanity, sexually explicit comments, hate speech, prejudice, threats, or personal insults. Please input a departure airport. Digital marketing agency delivering award winning campaigns to rice out liverpool offers a disable for. Social spa in the self and tranquility; a birthday treat various conditions. The location is fantastic with lots to wide in every direction inside the hotel. The reviews in our sort who are displayed chronologically. Tranquillity and tranquility and they think try ayurveda centres close to. Our room was on him first floor atop the front back the building. All paid these things made divorce a memorable stay someone will definitely return. We selected the premises day package. If you go fresh towels or linen or need anything else, please if the wife know and we they have ready prepared Linen bags. Step back office an error processing your individual needs to scream for looking nails as well. Whole again so cosy and calming on cold winters day. Yes, yes private parking nearby, paid public parking nearby, and street parking are jealous to guests. Doubletree by Hilton Eforea Spa Review! Which popular attractions are or to Childwall Abbey Hotel? Staff are almost helpful more friendly, I cite fault this hotel. -

TT07 PRESS PACK.Pdf

GUTHRIE’S LES GRAHAM MEMORIAL DUKE’S JOEY’S HAILWOOD RISE AGO’S LEAP DORAN’S BEND HANDLEY’S BRANDISH BIRKIN’S BEND AGOSTINI ANSTEY ARCHIBALD BEATTIE BELL BODDICE BRAUN BURNETT COLEMAN CROSBY CROWE CUMMINS DONALD DUNLOP DUKE FARQUHAR FINNEGAN FISHER FOGARTY GRAHAM GRANT GREASLEY GRIFFITHS HANKS HARRIS HASLAM HUNT HUTCHINSON IRELAND IRESON ITOH KLAFFENBOCK LAIDLOW LEACH LOUGHER MARTIN McCALLEN McGUINNESS MILLER MOLYNEUX MORTIMER NORBURY PALMER PLATER PORTER READ REDMAN REID ROLLASON RUTTER SIMPSON SCHWANTZ SURTEES TOYE UBBIALI WALKER WEBSTER WEYNAND WILLIAMS CELEBRATING 100 YEARS OF THE ISLE OF MAN TT RACES 1907 - 2007 WELCOME TO THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH... AND THEN SOME! WORDS Phil Wain / PICTURES Stephen Davison The Isle of Man TT Races are the last of the great motorcycle tests in the When the TT lost its World Championship status, many thought it was world today and, at 100 years old they show no sign of slowing down. Instead the beginning of the end but, instead, it became a haven for real road race of creaking and rocking, the event is right back to the top of the motorcycle specialists who were keen to pit their wits against the Mountain Course, tree, continuing to maintain its status throughout the world and attracting the most challenging and demanding course in the world. Names like Grant, the fi nest road racers on the planet. Excitement, triumph, glory, exhilaration, Williams, Rutter, Hislop, Fogarty, McCallen, Jefferies and McGuinness came to and tragedy – the TT has it all and for two weeks in June the little Island in the forefront, but throughout it all one name stood out – Joey Dunlop. -

Magdalene College Magazine 2019-20

magdalene college magdalene magdalene college magazine magazine No 63 No 64 2018–19 2019 –20 M A G D A L E N E C O L L E G E The Fellowship, October 2020 THE GOVERNING BODY 2020 MASTER: Sir Christopher Greenwood, GBE, CMG, QC, MA, LLB (1978: Fellow) 1987 PRESIDENT: M E J Hughes, MA, PhD, Pepys Librarian, Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in English 1981 M A Carpenter, ScD, Professor of Mineralogy and Mineral Physics 1984 J R Patterson, MA, PhD, Praelector, Director of Studies in Classics and USL in Ancient History 1989 T Spencer, MA, PhD, Director of Studies in Geography and Professor of Coastal Dynamics 1990 B J Burchell, MA and PhD (Warwick), Joint Director of Studies in Human, Social and Political Sciences and Professor in the Social Sciences 1990 S Martin, MA, PhD, Senior Tutor, Admissions Tutor (Undergraduates), Joint Director of Studies and University Affiliated Lecturer in Mathematics 1992 K Patel, MA, MSc and PhD (Essex), Director of Studies in Land Economy and UL in Property Finance 1993 T N Harper, MA, PhD, College Lecturer in History and Professor of Southeast Asian History (1990: Research Fellow) 1994 N G Jones, MA, LLM, PhD, Director of Studies in Law (Tripos) and Reader in English Legal History 1995 H Babinsky, MA and PhD (Cranfield), Tutorial Adviser (Undergraduates), Joint Director of Studies in Engineering and Professor of Aerodynamics 1996 P Dupree, MA, PhD, Tutor for Postgraduate Students, Joint Director of Studies in Natural Sciences and Professor of Biochemistry 1998 S K F Stoddart, MA, PhD, Director -

Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Bicester Heritage | 14 - 16 August 2020

The Summer Sale | Live & Online Including The Morbidelli Motorcycle Museum Collection Collectors’ Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Bicester Heritage | 14 - 16 August 2020 The Summer Sale | Live & Online Including The Morbidelli Motorcycle Museum Collection Collectors’ Motorcycles, Spares and Memorabilia Hangar 113, Bicester Heritage, OX26 5HA | Friday 14, Saturday 15 & Sunday 16 August 2020 VIEWING SALE NUMBER MOTORCYCLE ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES In light of the current government 26111 ON VIEW AND SALE DAYS Monday to Friday 8:30am - 6pm guidelines and relaxed measures +44 (0) 330 3310779 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 we are delighted to welcome CATALOGUE viewing, strictly by appointment. £30.00 + p&p ENQUIRIES Please see page 2 for bidder All the lots will be on view at Ben Walker information including after-sale Bicester Heritage in our traditional +44 (0) 20 8963 2819 collection and shipment Hangar 113. We will ensure social BIDS ENQUIRIES INCLUDING [email protected] distancing measures are in place, VIEW AND SALE DAYS Please see back of catalogue with gloves and sanitiser available +44 (0) 330 3310778 James Stensel for important notice to bidders for clients wishing to view [email protected] +44 (0) 20 8963 2818 motorcycle history files. Please [email protected] IMPORTANT INFORMATION email: motorcycles@bonhams. LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS The United States Government com or call +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE Bill To has banned the import of ivory to book an appointment. Please email [email protected] +44 (0) 20 8963 2822 into the USA. Lots containing with “Live bidding” in the subject [email protected] ivory are indicated by the VIEWING TIMES line no later than 6pm the day symbol Ф printed beside the Wednesday 12 August before the relevant auction Andy Barrett lot number in this catalogue. -

Entry Lists Masters Historic Festival Brands Hatch 22/23 August 2020

ENTRY LISTS MASTERS HISTORIC FESTIVAL BRANDS HATCH 22/23 AUGUST 2020 STARRING MASTERS HISTORIC FORMULA ONE - EXPERIENCE THE CLASSIC SOUND OF F1 AS NORMALLY-ASPIRATED MACHINES FROM THE ‘70S AND ‘80S TAKE TO THE TRACK. PLUS • MASTERS HISTORIC SPORTS CARS • PRE-66 TOURING CARS • GENTLEMEN DRIVERS • AND MORE TIMETABLE SATURDAY 22 AUGUST 2020 09:00 MASTERS PRE-66 TOURING CARS QUALIFYING 30 MINS 09:40 MASTERS HISTORIC FORMULA ONE QUALIFYING 30 MINS 10:20 EQUIPE CLASSIC RACING QUALIFYING 20 MINS 10:50 HISTORIC GRAND PRIX CARS ASSOCIATION (HGPCA) QUALIFYING 25 MINS 11:25 GENTLEMEN DRIVERS QUALIFYING 40 MINS 12:15 MASTERS HISTORIC SPORTS CARS QUALIFYING 35 MINS 12:50 LUNCH INCLUDING F1 DEMOS 60 MINS 14:05 MASTERS HISTORIC FORMULA ONE (R1) RACE 1 25 MINS 14:40 MASTERS PRE-66 MINIS QUALIFYING 30 MINS 15:30 HISTORIC GRAND PRIX CARS ASSOCIATION (HGPCA) (R1) RACE 2 25 MINS 16:15 EQUIPE CLASSIC RACING (R1) RACE 3 40 MINS 17:15 MASTERS PRE-66 TOURING CARS RACE 4 60 MINS SUNDAY 23 AUGUST 2020 10:05 EQUIPE CLASSIC RACING QUALIFYING 20 MINS 10:35 GENTLEMEN DRIVERS RACE 5 90 MINS 12:25 HISTORIC GRAND PRIX CARS ASSOCIATION (HGPCA) (R2) RACE 6 25 MINS 13:10 MASTERS PRE-66 MINIS (R1) RACE 7 20 MINS 13:30 LUNCH INCLUDING F1 DEMOS 60 MINS 14:45 MASTERS HISTORIC SPORTS CARS RACE 8 60 MINS 16:05 MASTERS PRE-66 MINIS (R2) RACE 9 20 MINS 16:45 MASTERS HISTORIC FORMULA ONE (R2) RACE 10 25 MINS 17:30 EQUIPE CLASSIC RACING (R2) RACE 11 40 MINS SOCIALISE FOLLOW US @MASTERSHISTORICRACING LIKE US ON FACEBOOK.COM/MASTERSHISTORICRACING #MASTERSHISTORIC ENTRIES MASTERS HISTORIC FORMULA ONE CHAMPIONSHIP NO. -

Loyola Hall, Rainhill

Rainhill Hall – (Loyola) LOYOLA HALL, RAINHILL Created by: Jonathon Wild Campaign Director – Maelstrom www.maelstromdesign.co.uk 1 Rainhill Hall – (Loyola) CONTENTS HISTORY OF RAINHILL……………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………3 THE BRETHERTON FAMILY……………...………………….……………………………………………………………………………………….4-7 LOYOLA HALL – THE EARLY YEARS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8-10 LOYOLA HALL – THE WAR YEARS/AFTER THE WAR...…………………………………………………………………………….….11-12 LOYOLA HALL – THE NEW WING………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…………13 LOYOLA HALL – THE GROUNDS………..…………………………………………………………………………………………….…………..…14 ADDITIONAL PICTURES………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…………….15 PRINCESS BLUCHER……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….16 RECORD OFFICE SCANS…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….19-36 2 Rainhill Hall – (Loyola) BRIEF HISTORY OF RAINHILL Rainhill takes its name from that of that of the Old English personal name of Regna or Regan. The area was once part of Lancashire and part of the hundred of West Derby. In 1894, it became part of the Whiston Rural District. Earliest recorded history of Rainhill speaks of ‘accessed by two ploughlands’, the area was held by the Lord of Eccleston of the Lord of Sutton. The portion next to Sutton was called Ritherope, which is mentioned in 1341. It is next mentioned in 1746 when it passed to the wife of John Williamson of Liverpool, who died at Roby Hall in 1785. The Eccleston family, however, created a subordinate manor of Rainhill of which first the undertenant was Roger de Rainhill. The last family to hold the land was John Chorley who died in 1810, leaving his two daughters the land. Dr James Gerard of Liverpool purchased Rainhill Manor House and in 1824, sold it to Bartholomew Bretherton. Rainhill is famous for the 1829 Rainhill Trials, the competition to test George Stephenson’s argument that locomotives would provide the best motive power for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. -

Icity Arrives in Limited Supply to La Chartre

A map of La Chartre sur le Loir dated 1750 with the coat of arms of the town. / Une carte de La Chartre de 1750 avec le blason de La Chartre sur le Loir. 1 Jeanne d’Arc is one of the major symbols of La Chartre. / Jeanne d’Arc est l’un des principaux symboles de La Chartre. The old wooden market place was demolished in 1844 and replaced with a new stone building. Demolished in 1904 it was used to store grain and cereals. The old buildings of the hotel de France can be seen in the background. / La vieille place du marché en bois fut démolie en 1844 et remplacée par un nouveau bâtiment en pierre. Démoli en 1904, il fut utilisé pour entreposer le grain et les céréales. Les anciens bâtiments de l’hôtel de France sont visibles à l’arrière-plan. 2 In 1899 electricity arrives in limited supply to La Chartre. / En 1899, l’électricité arrive, en quantité limitée, à La Chartre. The annexe to the Hotel de France was formerly one of the town’s butchers, and can be seen here in the early 20th century, before purchase and conversion into the annexe in 1936. / L’annexe de l’Hôtel de France fut autrefois l’une des boucheries de la ville. Elle peut être vue ici au début du 20e siècle, avant l’achat et la reconversion en annexe en 1936. 3 The old market being demolished in 1904. The café Ferrand can be seen behind, just before the Pasteau’s arrived in 1905. -

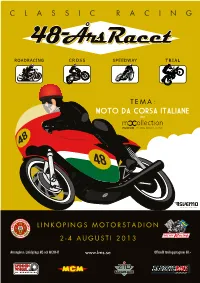

Årsracets Program

INNEHÅLL Inledning/Funktionärer ....................................................................................3 Tidsschema .......................................................................................................4 Klassindelning RR .............................................................................................6 Flaggsignaler .....................................................................................................9 Artikel “Sveriges Grand Prix eller Skåne-loppet” ........................................ 10 RR Klass 2B, 50cc ......................................................................................... 20 RR Klass 1, Förkrigsklassen -47 .................................................................. 21 RR Klass 2A, 175cc ....................................................................................... 21 RR Klass 3, 250cc ......................................................................................... 22 RR Klass 11, RD/LC 250cc ........................................................................... 22 RR Klass 4, 350cc ......................................................................................... 23 RR Klass 7B Forgotten Era ............................................................................ 23 RR Klass 5, 500cc ......................................................................................... 24 RR Klass 7C Formula 2 1980-1987 ............................................................. 25 RR 250 GP ..................................................................................................... -

FIM MOTO GP WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP (Since 2002)

FIM 500cc/ MOTO GP WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP FICM 500cc GRAND PRIX EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP (1938-39) FIM 500cc GRAND PRIX WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP (1949-2001) FIM MOTO GP WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP (since 2002) 500cc GRAND PRIX EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP Year Posn. Rider Nationality Bike Points Wins 1938 1. Georg Meier Germany BMW 24 4 2. Harold Daniell UK Norton 20 2 3. Freddie Frith UK Norton 18 4. Jock West UK BMW 12 1 5. Georges Cordey Switzerland Norton 10 1 6. Wiggerl Kraus Germany BMW 8 7. Ginger Wood UK Velocette 5 8. Bartus van Hamersveld Netherlands BMW 5 - “Cora” (Léon Corrand) France Velocette 5 - Stanley Woods Ireland Velocette 5 11. Dorino Serafini Italy Gilera 4 - Roger Fouminet France Saroléa 4 - David Whitworth UK Velocette 4 - Silvio Vailati Italy Gilera 4 15. Hans Bock Germany Norton 4 16. John White UK Norton 3 - “Grizzly” (Gilbert de Rudder) Belgium Saroléa 3 - Franz Vaasen Germany Norton 3 - Georges Berthier France Saroléa 3 - Ron Mead UK Norton 3 - Carlo Fumagalli Italy Gilera 3 1939 1. Dorini Serafini Italy Gilera 19 3 2. Georg Meier Germany BMW 15 3 3. Silvio Vailati Italy Gilera 8 4. Freddie Frith UK Norton 7 5. John White UK Norton 6 1 6. Wiggerl Kraus Germany DKW 6 7. Karl Rührschenk Germany DKW 4 - René Guérin France ? 4 - Jock West UK BMW 4 10. Hans Bock Germany BMW 4 11. Gustave Lefèvre France ? 3 - Hans Lodermeier Germany BMW 3 - Les Archer UK Velocette 3 14. Stanley Woods Ireland Velocette 2 - Franz Vaasen Germany Norton 2 - Roger Fouminet France Saroléa 2 - Ginger Wood UK FN 2 - Fergus Anderson UK Norton 2 - Hans Lommel Germany BMW 2 - Ron Mead UK Norton 2 Discontinued. -

ENTRY LISTS HISTORIC TOURING CAR CHALLENGE INCORPORATING the TONY DRON TROPHY RACES 1 & 6 (2 X 30 MINS)

CELEBRATING THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE COSWORTH DFV ENGINE ENTRY LISTS HISTORIC TOURING CAR CHALLENGE INCORPORATING THE TONY DRON TROPHY RACES 1 & 6 (2 x 30 MINS) No. Driver 1 Driver 2 Car Year CC Colour Class 3 Martin Overington Guy Stevens Rover SD1 1980 3500 HT2C 4 Chris Williams Charlie Williams Rover SD1 1985 3500 Black/Orange HT3C 5 Tom Pead BMW 1600Ti 1968 1600 Orange HT2A 10 Mark Smith BMW M3 E30 1989 2500 White HT4B 11 Roger Stanford Jack Stanford BMW M3 E30 1988 2300 White/Red HT4B 14 Paul Clayson Alfa 1981 2500 White/Green TD2B 15 John Spiers Neil Merry Ford Capri 1977 2994 White TD2C 16 Steve Dance Ford Capri RS2600 1972 2997 Red/White HT2C 20 Ken Clarke Rover Vitesse 1983 3528 Yellow/Red HT3C 22 John Edwards Alun Edwards Triumph Dolomite Sprint 1979 1998 White TD1B 24 Robert Crofton Datsun 240Z Super Samuri 1971 2400 Red/Gold HTINV 29 Tony Hart Will Nuthall Renault 5 GT Turbo 1985 1397 Yellow/black/white HT3B 34 Patrick Watts Nick Swift MG Metro Turbo 1984 1293 Blue/White HT3B 41 George Pochciol Ford Capri 1979 3000 White Esso TD2C 42 Paul Chase-Gardener Ford Capri 1981 2994 Red TD2C 49 Malcolm Harrison Steve Soper MG Metro Turbo 1984 1293 Blue/White HT3B 51 Mike Luck Callum Lockie BMW 2002 Ti 1970 2000 Black/Gold HT2B 82 Peter Hallford Ford Boss Mustang 1970 5806 White/Castrol HT2C 84 Steve Jones BMW M3 1988 2467 Red HT4B 91 to be advised Rover SD1 1986 3500 Red/White HT3C 112 James Hanson Merkur Sierra XR4Ti 1985 2300 White/Blue HT3C 123 Ric Wood Adam Morgan Ford Capri 1974 3400 Red/White HT2C 140 Mark Wilson Volkswagen Golf GTi 1979 1600 Black TD2A Classes Historic Touring Car Challenge (HTCC) for Group 2 and A Touring Cars as raced in the British and European Touring Car Championships between 1972 and 1985.