The Architecture of Dublin's Neo-Classical Roman Catholic Temples 1803-62

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dublin 9, Ireland

DAIICHI SANKYO IRELAND LTD. TEL: 00 353 (0) 1 4893000 Unit 29, Block 3 FAX: 00 353 (0) 1 4893033 Northwood Court, www.daiichi-sankyo.ie Santry, Dublin 9, Ireland Travel Information M1 From the city centre Follow the signs for Dublin Airport/M1. Once you join the dual carriageway at Whitehall, proceed N1 towards the airport. From this road take the second exit, signed for Santry/Coolock/Beaumont. N3 Once at the top of the exit ramp take a left towards Santry. Continue to the t-junction and once Dublin Airport there, you will see a public park ahead. Take a right-hand turn and proceed past the National We Are Running (Morton) Stadium. The Swords Road entrance for Northwood Business Campus is on your left-hand side. Proceed to the first roundabout and take first exit and take first right. Take second Here M1 left for our car park. R104 From other parts of Dublin Leixlip M50 R807 Follow the signs for the M50. If coming from the south or west, take the northbound route M4 towards the airport. Proceed towards Exit 4, signposted as Ballymun/Naul. Follow signs from the N4 Dublin motorway for Ballymun. Once at the bottom of the exit ramp you will see a slip road to your left, with the Northwood Business Campus entrance directly ahead. Enter the business campus and go Irish Sea straight through the first roundabout (a retail park will be on your left). Take the first right. M50 Entrance to the car park is on the third right. N11 Dalkey Clane N7 N81 By Air R119 Dublin Airport is just 2km from Northwood Business Campus. -

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

'Dublin's North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960S'

Edinburgh Research Explorer Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s Citation for published version: Hanna, E 2010, 'Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s', Historical Journal, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 1015-1035. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Historical Journal Publisher Rights Statement: © Hanna, E. (2010). Dublin’s North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960s. Historical Journal, 53(4), 1015-1035doi: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here DUBLIN'S NORTH INNER CITY, PRESERVATIONISM, AND IRISH MODERNITY IN THE 1960S ERIKA HANNA The Historical Journal / Volume 53 / Issue 04 / December 2010, pp 1015 - 1035 DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X10000464, Published online: 03 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X10000464 How to cite this article: ERIKA HANNA (2010). -

Introduction to the Normanton Papers

INTRODUCTION NORMANTON PAPERS November 2007 Normanton Papers (T3719) Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................2 Agar's posthumous reputation .................................................................................4 Agar's archive ..........................................................................................................8 A re-assessment of Agar? .....................................................................................12 Public Record Office of Northern Ireland 1 Crown Copyright 2007 Normanton Papers Introduction The Normanton papers, which run from 1741 to 1809, are the letters and papers of Archbishop Charles Agar, 1st Earl of Normanton (1735-1809), third son of Henry Agar (1707- 46) of Gowran, Co. Kilkenny, by his wife, Anne (1707–1765), daughter of Welbore Ellis, Bishop of Meath, and a younger brother of James Agar, 1st Viscount Clifden (1734-1789). The Agars of Gowran owned c.20,000 statute acres in Co. Kilkenny, and controlled the two south Kilkenny boroughs of Gowran and Thomastown. This gave them a minimum of four seats in the Irish House of Commons, plus a fifth when an Agar was elected for the county of Kilkenny. On the strength of this considerable parliamentary influence, Bookplace of Charles Agar, Earl of Normanton Charles Agar's eldest brother, James (1734–1789), was created Baron Clifden in 1776 and Viscount Clifden in 1781. Charles Agar's ecclesiastical career began with his appointment -

![Trench Pedigree [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5627/trench-pedigree-microform-225627.webp)

Trench Pedigree [Microform]

12 3 4 5 6 7 1 TEENCH PEDIGBEE. FREDERIC DE LA TRANCHE, or TRENCH, a Protestant, passed into England in consequence of the civil wars in France upon the subject of religion, and esta blished himself in Northumberland, in1574-5 ; m.(1576) Margaret, daughter of—Sutton, Esq. l.Thomas (M.A.in1599), m. 1610 Catherine, daughter of Richard Brooke, ofPontefract, formerly merchant in London. FREDERIC (came to Ireland 1631 ;purchased Garbally, in County Galway) ;d. 1669 ;m. 1632 his cousin-german Anna (only daughter and heiress ofRev. James Trench — see below, page 2), who d. 1664. His sons Frederic and John are the ancestors re spectively of the families of Clancarty and Ashtown. 1. FREDERIC (ofGarbally), b.1633 ;d. 1704 ;received grants of lands from the Crown ;m. Elizabeth, daughter of Richard "Warburton, of Garryhinch, King's County. 1.Frederic (M.P. for County Galway), b. 1681 ;d. 1752 ;m. 1703 Elizabeth, daughter of John Eyre, Esq., of Eyrecourt Castle, County Galway. l.Richard (Colonel ofMilitia,County Galway), b.1710 ; d. 1768 ;m. 1732 Frances (only daughter and heiress of David Power, Esq., of Gooreen, County Galway), who d. 1793. l.William Power Keating, b. 1741 ;d. 27 April 1805 ;m, 1762 Anne (daughter of Right Hon. Charles Gardiner); Ist Earl ofCLAITCART7. See Clancarty Genealogy. 2. John Power (Collector of District of Loughrea, County Galway). 3. Eyre Power (Major-General) ; m. 1797 Char lotte, widowof Sir John Burgoyne, Bart., and daughter of Gen. Johnstone, of Overstone. 4. .Nicholas Power (Collector of the Port and Dis trict of Galway) ;d. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Habitats Phase I & II Flora

Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Habitats Phase I & II Flora Fingal County Council November 2004 Supported by Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Phase I & II Habitats & Flora Prepared by: Dr. D. Doogue, Ecological Consultant D. Tiernan, Fingal County Council, Parks Division H. Visser, Fingal County Council, Parks Division November 2004 Supported by Michael A. Lynch, Senior Parks Superintendent. Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Objectives 2 1.2 The Study Area 3 1.3 Acknowledgements 4 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1 The Habitat Mapping 6 2.2 The Vegetation Survey 6 2.3 The Rare Plant Survey 6 3 RESULTS 3.1 Habitat Classes 8 3.1.1 The Coastland 8 3.1.1.1 Rocky Sea Cliffs 8 3.1.2.2 Sea stacks and islets 9 3.1.1.3 Sedimentary sea cliffs 9 3.1.1.4 Shingle and Gravel banks 10 3.1.1.5 Embryonic dunes 10 3.1.1.6 Marram dunes 11 3.1.1.7 Fixed dunes 11 3.1.1.8 Dune scrub and woodland 12 3.1.1.9 Dune slacks 12 3.1.1.10 Coastal Constructions 12 3.1.2 Estuaries 12 3.1.2.1 Mud shores 13 3.1.2.2 Lower saltmarsh 13 3.1.2.3 Upper saltmarsh 14 3.1.3 Seashore 15 3.1.3.1 Sediment shores 15 3.1.3.2 Rocky seashores 15 3.2 Habitat Maps & Site Reports 16 3.2.1 Delvin 17 3.2.2 Cardy Point 19 3.2.3 Balbriggan 21 3.2.4 Isaac’s Bower 23 3.2.5 Hampton 26 3.2.6 Skerries – Barnageeragh 28 3.2.7 Red Island 31 3.2.8 Skerries Shore 31 3.2.9 Loughshinny 33 3.2.10 North Rush to Loughshinny 37 3.2.11 Rush Sandhills 38 3.2.12 Rogerstown Shore 41 3.2.13 Portrane Burrow 43 3.2.14 Corballis 46 3.2.15 Portmarnock 49 3.2.16 The Howth Peninsula 56 4. -

A Social Profile 2007-2015

Ballymun: A Social Profile 2007-2015 Research carried out by Brian Harvey with the assistance of youngballymun 2015 youngballymun Axis Arts Centre Main Street, Ballymun Dublin 9 www.youngballymun.org Executive summary Background This report, researched by Brian Harvey with the assistance of youngballymun, provides a social profile of Ballymun, Dublin over the pivotal years 2007-2015, presented on the basis of the censi (2006, 2011), published reports, interviews and information provided by voluntary and statutory providers and public representatives. The profile looks at demographic and related change; services and investment; the impact of socio-economic change; and future challenges. Demographic change Over this period, the population of Ballymun grew moderately and aged, with considerable internal movement. The population became more diverse, but the number of Travellers fell. There is a high rate of lone parent households. There was upward social mobility, less early school leaving and a small rise in third level participation. The proportion of people reporting the ability to speak Irish fell. There was a growth in the use of cars, internet and computers. The proportion of local authority housing fell, while private rented accommodation rose. Crime rates fell. In the context of reduced incomes and rising poverty Ballymun remains one of the most disadvantaged communities in Dublin, with high rates of unemployment. For children, the value of Child Benefit payment fell, while the introduction of the Free Pre-School Year represented an investment of about a third the value of the previous Early Childcare Supplement which it replaced. Reduced investment Ballymun suffered from the national disinvestment in social and related services in general and in the voluntary and community sector in particular. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Whitechurch Stream Flood Alleviation Scheme

WHITECHURCH STREAM FLOOD ALLEVIATION SCHEME Environmental Report MDW0825 Environmental Report F01 06 Jul. 20 rpsgroup.com WHITECHURCH STREAM FAS-ER Document status Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by Review date A01 For Approval HC PC MD 09/04/20 A02 For Approval HC PC MD 02/06/20 F01 For Issue HC PC MD 06/07/20 Approval for issue Mesfin Desta 6 July 2020 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced, by any means, without the written permission of RPS Group Limited. -

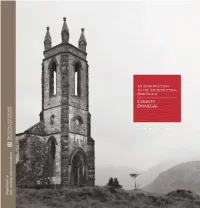

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system.