Introduction to the Normanton Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Trench Pedigree [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5627/trench-pedigree-microform-225627.webp)

Trench Pedigree [Microform]

12 3 4 5 6 7 1 TEENCH PEDIGBEE. FREDERIC DE LA TRANCHE, or TRENCH, a Protestant, passed into England in consequence of the civil wars in France upon the subject of religion, and esta blished himself in Northumberland, in1574-5 ; m.(1576) Margaret, daughter of—Sutton, Esq. l.Thomas (M.A.in1599), m. 1610 Catherine, daughter of Richard Brooke, ofPontefract, formerly merchant in London. FREDERIC (came to Ireland 1631 ;purchased Garbally, in County Galway) ;d. 1669 ;m. 1632 his cousin-german Anna (only daughter and heiress ofRev. James Trench — see below, page 2), who d. 1664. His sons Frederic and John are the ancestors re spectively of the families of Clancarty and Ashtown. 1. FREDERIC (ofGarbally), b.1633 ;d. 1704 ;received grants of lands from the Crown ;m. Elizabeth, daughter of Richard "Warburton, of Garryhinch, King's County. 1.Frederic (M.P. for County Galway), b. 1681 ;d. 1752 ;m. 1703 Elizabeth, daughter of John Eyre, Esq., of Eyrecourt Castle, County Galway. l.Richard (Colonel ofMilitia,County Galway), b.1710 ; d. 1768 ;m. 1732 Frances (only daughter and heiress of David Power, Esq., of Gooreen, County Galway), who d. 1793. l.William Power Keating, b. 1741 ;d. 27 April 1805 ;m, 1762 Anne (daughter of Right Hon. Charles Gardiner); Ist Earl ofCLAITCART7. See Clancarty Genealogy. 2. John Power (Collector of District of Loughrea, County Galway). 3. Eyre Power (Major-General) ; m. 1797 Char lotte, widowof Sir John Burgoyne, Bart., and daughter of Gen. Johnstone, of Overstone. 4. .Nicholas Power (Collector of the Port and Dis trict of Galway) ;d. -

No Good Deed Goes Unpunished the Preservation and Destruction of the Christ Church Cathedral Deeds Stuart Kinsella

Archive Fever, no. 10 (December 2019) No Good Deed Goes Unpunished The Preservation and Destruction of the Christ Church Cathedral Deeds Stuart Kinsella ‘Many charters were left scarcely legible, and particularly a foundation charter of King Henry II … could not by any means be read; the prior applied to the Barons of the Exchequer to enroll such of their deeds as were not wholly destroyed, and leave was accordingly given’ Image: Portrait of Michael Joseph McEnery, M.R.I.A., as printed in the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Sixth Series, 14, no. 1 (1924): frontispiece. Beyond 2022 Archive Fever no. 10 (December, 2019) 1 | Page Archive Fever, no. 10 (December 2019) The Christ Church deeds were the oldest collection of material in the Public Record Office of Ireland. During the restoration of Christ Church in the 1870s, the cathedral authorities felt it wise to deposit the cathedral’s vast collection of medieval and early modern materials for safe keeping in the newly minted Public Record Office of Ireland, established in 1867, unaware, of course, that the materials would survive unscathed for only four decades.1 To the immense relief of posterity, a then junior civil servant in the office of the deputy keeper, was assigned to produce a calendar of the cathedral records, summarising them into English mostly from Latin and a few from French. Michael J. McEnery was his name, who began work in 1883, and was almost complete by 1884. He published them as appendices to the reports of the deputy keeper in 1888, 1891, 1892, with an index in 1895 up to the year 1602. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin 13th-20th cent. Transferred from St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, 1995-2002, 2012 GENERAL ARRANGEMENT C2.1. Volumes C2.2. Deeds C2.3. Maps C2.4. Plans and Drawings C2.5. Loose Papers C2.6. Photographs C.2.7. Printed Material C.2.8. Seals C.2.9. Music 2 1. VOLUMES 1.1 Dignitas Decani Parchment register containing copies of deeds and related documents, c.1190- 1555, early 16th cent., with additions, 1300-1640, by the Revd John Lyon in the 18th cent. [Printed as N.B. White (ed) The Dignitas Decani of St Patrick's cathedral, Dublin (Dublin 1957)]. 1.2 Copy of the Dignitas Decani An early 18th cent. copy on parchment. 1.3 Chapter Act Books 1. 1643-1649 (table of contents in hand of John Lyon) 2. 1660-1670 3. 1670-1677 [This is a copy. The original is Trinity College, Dublin MS 555] 4. 1678-1690 5. 1678-1713 6. 1678-1713 (index) 7. 1690-1719 8. 1720-1763 (table of contents) 9. 1764-1792 (table of contents) 10. 1793-1819 (table of contents) 11. 1819-1836 (table of contents) 12. 1836-1860 (table of contents) 13. 1861-1982 1.4 Rough Chapter Act Books 1. 1783-1793 2. 1793-1812 3. 1814-1819 4. 1819-1825 5. 1825-1831 6. 1831-1842 7. 1842-1853 8. 1853-1866 9. 1884-1888 1.5 Board Minute Books 1. 1872-1892 2. 1892-1916 3. 1916-1932 4. 1932-1957 5. -

THE LONDON Gfaz^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237

THE LONDON GfAZ^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237 ; '.' "• Y . ' '-Downing,Street. Charles, Earl of-Leitrim. '-'--•'. ' •' July 5, 1904. jreorge, Earl of Lucan. The KING has been pleased to approve of the Somerset Richard, Earl of Belmore. appointment of Hilgrpye Clement Nicolle, Esq. Tames Francis, Earl of Bandon. (Local Auditor, Hong Kong), to be Treasurer of Henry James, Earl Castle Stewart. the Island of Ceylon. Richard Walter John, Earl of Donoughmore. Valentine Augustus, Earl of Kenmare. • William Henry Edmond de Vere Sheaffe, 'Earl of Limericks : i William Frederick, Earl-of Claricarty. ''" ' Archibald Brabazon'Sparrow/Earl of Gosford. Lawrence, Earl of Rosse. '• -' • . ELECTION <OF A REPRESENTATIVE PEER Sidney James Ellis, Earl of Normanton. FOR IRELAND. - Henry North, -Earl of Sheffield. Francis Charles, Earl of Kilmorey. Crown and Hanaper Office, Windham Thomas, Earl of Dunraven and Mount- '1st July, 1904. Earl. In pursuance of an Act passed in the fortieth William, Earl of Listowel. year of the reign of His Majesty King George William Brabazon Lindesay, Earl of Norbury. the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Uchtef John Mark, Earl- of Ranfurly. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Jenico William Joseph, Viscount Gormanston. " the Commons, to serve ia the Parliament of the Henry Edmund, Viscount Mountgarret. " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be Victor Albert George, Viscount Grandison. n summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Harold Arthur, Viscount Dillon. I do hereby-give Notice, that Writs bearing teste Aldred Frederick George Beresford, Viscount this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer Lumley. of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by the James Alfred, Viscount Charlemont. -

William Ives Test Indexed

Index of Names A Robert....................................................3538 A........................................................................ Abraham............................................................ Annis.......................................................900 Christopher............................................3543 Caroline.......................................1220, 2007 Kenneth.................................................3543 Catharine.................................................466 Kyle.......................................................3543 Cora.............................................2531, 3180 Mary Elizabeth......................................2864 Dorothy.......................................2666, 3246 Timothy W............................................3543 Elizabeth.................................................943 Woodrow Wilson T.....................2139, 2865 Esther..........................................2886, 3375 Ackeret.............................................................. Francis...........................................692, 1285 Gotleib........................................3394, 3527 Lucinda.................................................1188 Ackerman.......................................................... Lucy..................................1990, 1991, 2743 Rebecca Ann...............................1008, 1704 Martha...............................1195, 1951, 2697 Ackert................................................................ Mary..................................1833, -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

CNI Irish News Bulletin 1St February 2014

CNI Irish news bulletin 1st February 2014 Irish news bulletin 1st February Liz Hughes: The woman who's in running to lead Presbyterian flock The Presbyterian Church has nominated a woman among its five candidates for the election of a new Moderator next week. Alf McCreary in Belfast Telegraph - Reverend Liz Hughes, of Whitehouse Presbyterian in Newtownabbey, is only the second women to have been nominated by the Church. Presbyterians were the first of the main churches in Ireland to ordain women ministers many years ago. If elected, she will be the first woman Moderator of the Church and will follow in the footsteps of two other newly- appointed female Church leaders in Ireland. Rev Dr Heather Morris became the first Methodist president last year, and Rev Pat Storey, from Londonderry, became the first female Anglican bishop to be appointed in the British Isles when she was installed as Bishop of Meath and Kildare just before Christmas. Rev Hughes, who is currently attending a Church seminar in the US, told the Belfast Telegraph: "I prayed a great deal before deciding to accept the nomination and I will be very happy to accept the outcome, whatever it may be." Page 1 CNI Irish news bulletin 1st February 2014 She is a well-known figure throughout the Church but she will face stiff competition from the four shortlisted men – Rev Michael Barry of First Newry; Rev Robert Herron from Omagh; Rev Ian McNie from Ballymoney, and Rev Alistair Smyth from Carryduff. This year's election is unusual because all the ministers are first-time candidates in a contest that normally contains names from the previous year's list. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

John Bryn Roberts Collection, (GB 0210 JBROBERTS)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - John Bryn Roberts Collection, (GB 0210 JBROBERTS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/john-bryn-roberts-collection-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/john-bryn-roberts-collection-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk John Bryn Roberts Collection, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

A History of the County Dublin; the People, Parishes and Antiquities from the Earliest Times to the Close of the Eighteenth Cent

A^ THE LIBRARY k OF ^ THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^ ^- "Cw, . ^ i^^^ft^-i' •-. > / • COUNTY ,r~7'H- O F XILDA Ji£ CO 17 N T r F W I C K L O \^ 1 c A HISTORY OF THE COUNTY DUBLIN THE PEOPLE, PARISHES AND ANTIQUITIES FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE CLOSE OF THE FIGIITKFXTH CENTURY. PART THIRD Beinsj- a History of that portion of the County comprised within the Parishes of TALLAGHT, CRUAGH, WHITEGHURCH, KILGOBBIN, KILTIERNAN, RATHMIGHAEL, OLD GONNAUGHT, SAGGART, RATHCOOLE. AND NEWGASTLE. BY FRANXIS ELRINGTON BALL. DUBLIN: Printed and Published hv Alex. Thom & Co. (Limited), Abbuv-st. 1905. :0 /> 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD PART. To the readers who ha\c sliowii so ;^fiitifyiii^' an interest in flio progress of my history there is (hie an apolo^^y Tor the tinu; whieli has e]a|)se(l since, in the preface to the seroml pai't, a ho[)e was ex[)rcsse(l that a further Jiistalnient wouhl scjoii ap])eai-. l^lie postpononient of its pvil)lication has l)een caused hy the exceptional dil'licuhy of ohtaiiiin;^' inl'orniat ion of liis- torical interest as to tlie district of which it was j^roposed to treat, and even now it is not witliout hesitation that tliis [)art has heen sent to jiress. Its pages will he found to deal with a poidion of the metro- politan county in whitdi the population has heen at no time great, and in whi(di resid( ncc^s of ini])ortanc(> have always heen few\ Su(di annals of the district as exist relate in most cases to some of the saddest passages in Irish history, and tell of fire and sw^ord and of destruction and desolation. -

The Honourable Thomas Charles Reginald Agar-Robartes MP (1880–1915)

‘A VEry EnglisH Gentleman’ The HoNourAble Thomas Charles Reginald Agar-robArtEs Mp (1880–1915) The death of Captain the Honourable Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- Robartes MP, at Loos during the First World War, robbed Great Britain of a talented, charismatic and hard-working politician. Paul Holden, House and Collections Manager at Lanhydrock House in Cornwall (the Agar-Robartes family estate), assesses the life and career of this backbench Liberal MP who served in the great reforming Liberal governments between 1906 and 1915 – ‘a very English gentleman’.1 8 Journal of Liberal History 66 Spring 2010 ‘A VEry EnglisH Gentleman’ The HoNourAble Thomas Charles Reginald Agar-robArtEs Mp (1880–1915) o his Cornish constituents of the evolving Liberal Party in understandably suffered, his exas- Agar-Robartes’ popular- Cornwall brought him a peer- perated tutor writing to Viscount ity was based as much on age. His only son Thomas Charles Clifden in 1902, saying: ‘I have his colourful character as (1844–1930) took the Liberal seat done my utmost for him’.5 on his impartial mind and of East Cornwall in 1880, a seat he After an unsuccessful attempt Tindependent stance. Amongst his held for two years before succeed- to join the army Tommy ventured peers he was a much admired and ing his father as Baron Robartes into politics. In 1903 the West- gregarious talent whose serious- in1882. ern Daily Mercury enthusiastically ness and moderation sometimes Tommy was one of ten chil- reported on his speech for the gave way before an erratic – and dren born into the high-Angli- Liberal Executive at Liskeard: ‘He often misplaced – wit that drew can family of Thomas Charles spoke with ease and confidence attention to his youth.2 Agar-Robartes (later 6th Viscount and his remarks were salted with Nine generations prior to Clifden), and Mary Dickinson wit … he gives promise of achiev- Tommy’s birth, Richard Robar- (1853–1921) of Kingweston in ing real distinction as a speaker.’6 tes (c.1580–1634), regarded as the Somerset (Fig.3). -

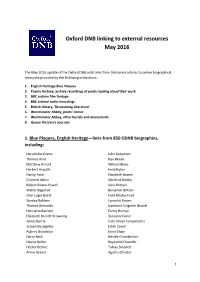

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens