Digital Government Review of Sweden Towards a Data-Driven Public Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2Nd FIR Council Meeting 2013 Friday 6 September

FIR – Fédération Internationale de Racketlon To FIR Council Members Leopoldstr. 21/5/12 A - 3400 Klosterneuburg Austria/Europe Tel/Fax: +43/2243/30488 E-mail: [email protected] Klosterneuburg 4th October 2013 2nd FIR Council Meeting 2013 Friday 6th September 22:00 – 23:30 Austrian Open/Wr. Neudorf/Austria Present: Marcel Weigl, Lennart Eklundh, Phil Todd, Nathalie Zeoli Excused: Karim Hanna, Puzant Kassabian, Dany Lessard, Poku Salo, Ahmad Bahadli Agenda 1) Welcome Note, FIR Members 2) Sportaccord application (Marcel) 3) Resultreporter/Tournament Software (Marcel) 4) Social Media (Phil) 5) World Tour 2014 (Marcel) 6) Finances (Lennart) 7) Marketing (Nathalie) 8) Requests to the Council 1) Welcome note, FIR Members (Marcel Weigl) Croatia and Turkey have been admitted as FIR members 41 and 42 A new representative for Malaysia has been found USA needs to move federation Italian federation to confirm new members FIR Council Decision: Because FIR still urgently needs members. From 2014 players of Non-FIR members may not participate in FIR world tour events. Big hopes for the future: Lebanon Marc Mourad Japan Hirona Sudo Luxemburg Tony Nightingale Qatar Alexandru Rosca Iceland Arnþór Jón Þorvarðsson Ghana Conny Schmickl Nepal Manoranjan Mishra Norway Lennart Eklundh Further Possibilities: Portugal Luis Barbossa, Jacob de Bangladesh Manoranjan Mishra Vries China Thorsten Deck Ukraine Aija Klaseva Dubai Andy Holmes Wales Peter Bridgeman Eygpt Karim Hanna Zimbabwe Jessica Calder FIR – Fédération Internationale de Racketlon Tel/Fax: +43-2243-30488 -

ATP World Tour 2019

ATP World Tour 2019 Note: Grand Slams are listed in red and bold text. STARTING DATE TOURNAMENT SURFACE VENUE 31 December Hopman Cup Hard Perth, Australia Qatar Open Hard Doha, Qatar Maharashtra Open Hard Pune, India Brisbane International Hard Brisbane, Australia 7 January Auckland Open Hard Auckland, New Zealand Sydney International Hard Sydney, Australia 14 January Australian Open Hard Melbourne, Australia 28 January Davis Cup First Round Hard - 4 February Open Sud de France Hard Montpellier, France Sofia Open Hard Sofia, Bulgaria Ecuador Open Clay Quito, Ecuador 11 February Rotterdam Open Hard Rotterdam, Netherlands New York Open Hard Uniondale, United States Argentina Open Clay Buenos Aires, Argentina 18 February Rio Open Clay Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Open 13 Hard Marseille, France Delray Beach Open Hard Delray Beach, USA 25 February Dubai Tennis Championships Hard Dubai, UAE Mexican Open Hard Acapulco, Mexico Brasil Open Clay Sao Paulo, Brazil 4 March Indian Wells Masters Hard Indian Wells, United States 18 March Miami Open Hard Miami, USA 1 April Davis Cup Quarterfinals - - 8 April U.S. Men's Clay Court Championships Clay Houston, USA Grand Prix Hassan II Clay Marrakesh, Morocco 15 April Monte-Carlo Masters Clay Monte Carlo, Monaco 22 April Barcelona Open Clay Barcelona, Spain Hungarian Open Clay Budapest, Hungary 29 April Estoril Open Clay Estoril, Portugal Bavarian International Tennis Clay Munich, Germany Championships 6 May Madrid Open Clay Madrid, Spain 13 May Italian Open Clay Rome, Italy 20 May Geneva Open Clay Geneva, Switzerland -

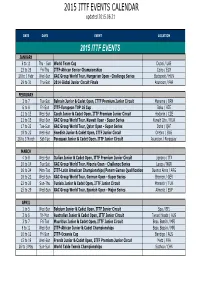

2015 ITTF EVENTS CALENDAR Updated 2015.06.21

2015 ITTF EVENTS CALENDAR updated 2015.06.21 DATE DAYS EVENT LOCATION 2015 ITTF EVENTS JANUARY 8 to 11 Thu - Sun World Team Cup Dubai / UAE 23 to 29 Fri-Thu ITTF-African Senior Championships Cairo / EGY 28 to 1 Febr Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Hungarian Open - Challenge Series Budapest / HUN 29 to 31 Thu-Sat 2014 Global Junior Circuit Finals Asuncion / PAR FEBRUARY 3 to 7 Tue-Sat Bahrain Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Manama / BRN 6 to 8 Fri-Sun ITTF-European TOP 16 Cup Baku / AZE 11 to 15 Wed-Sun Czech Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Hodonin / CZE 11 to 15 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Kuwait Open - Super Series Kuwait City / KUW 17 to 22 Tue-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Qatar Open - Super Series Doha / QAT 18 to 22 Wed-Sun Swedish Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Orebro / SWE 28 to 3 March Sat-Tue Paraguay Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Asuncion / Paraguay MARCH 4 to 8 Wed-Sun Italian Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Premium Junior Circuit Lignano / ITA 10 to 14 Tue-Sat GAC Group World Tour, Nigeria Open - Challenge Series Lagos / NGR 16 to 24 Mon-Tue ITTF-Latin American Championships/Panam Games Qualification Buenos Aires / ARG 18 to 22 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, German Open - Super Series Bremen / GER 22 to 26 Sun-Thu Tunisia Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Monastir / TUN 25 to 29 Wed-Sun GAC Group World Tour, Spanish Open - Major Series Almeria / ESP APRIL 1 to 5 Wed-Sun Belgium Junior & Cadet Open, ITTF Junior Circuit Spa / BEL 3 to 6 Fri-Mon Australian Junior & Cadet Open, -

The Racist Legacy in Modern Swedish Saami Policy1

THE RACIST LEGACY IN MODERN SWEDISH SAAMI POLICY1 Roger Kvist Department of Saami Studies Umeå University S-901 87 Umeå Sweden Abstract/Resume The Swedish national state (1548-1846) did not treat the Saami any differently than the population at large. The Swedish nation state (1846- 1971) in practice created a system of institutionalized racism towards the nomadic Saami. Saami organizations managed to force the Swedish welfare state to adopt a policy of ethnic tolerance beginning in 1971. The earlier racist policy, however, left a strong anti-Saami rights legacy among the non-Saami population of the North. The increasing willingness of both the left and the right of Swedish political life to take advantage of this racist legacy, makes it unlikely that Saami self-determination will be realized within the foreseeable future. L'état suédois national (1548-1846) n'a pas traité les Saami d'une manière différente de la population générale. L'Etat de la nation suédoise (1846- 1971) a créé en pratique un système de racisme institutionnalisé vers les Saami nomades. Les organisations saamies ont réussi à obliger l'Etat- providence suédois à adopter une politique de tolérance ethnique à partir de 1971. Pourtant, la politique précédente de racisme a fait un legs fort des droits anti-saamis parmi la population non-saamie du nord. En con- séquence de l'empressement croissant de la gauche et de la droite de la vie politique suédoise de profiter de ce legs raciste, il est peu probable que l'autodétermination soit atteinte dans un avenir prévisible. 204 Roger Kvist Introduction In 1981 the Supreme Court of Sweden stated that the Saami right to reindeer herding, and adjacent rights to hunting and fishing, was a form of private property. -

Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Budget Estimates Hearing 27 May-6 June 2013 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department/Agency: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Outcome/Program: 1.1 Prime Minister and Cabinet Topic: Hospitality and Entertainment Senator: Senator Ryan Question reference number: 77 Type of Question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 12 July 2013 Number of pages: 5 Question: What is the Department/Agency's hospitality spend for this financial year to date? Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. For each Minister and Parliamentary Secretary office, please detail total hospitality spend for this financial year to date. Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. What is the Department/Agency's entertainment spend for this financial year to date? Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. For each Minister and Parliamentary Secretary office, please detail total entertainment spend for this financial year to date. Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. What hospitality spend is the Department/Agency's planning on spending? Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. For each Minister and Parliamentary Secretary office, what hospitality spend is currently being planned for? Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. What entertainment spend is the Department/Agency's planning on spending? Detail date, location, purpose and cost of all events including any catering and drinks costs. -

Internal Politics and Views on Brexit

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8362, 2 May 2019 The EU27: Internal Politics By Stefano Fella, Vaughne Miller, Nigel Walker and Views on Brexit Contents: 1. Austria 2. Belgium 3. Bulgaria 4. Croatia 5. Cyprus 6. Czech Republic 7. Denmark 8. Estonia 9. Finland 10. France 11. Germany 12. Greece 13. Hungary 14. Ireland 15. Italy 16. Latvia 17. Lithuania 18. Luxembourg 19. Malta 20. Netherlands 21. Poland 22. Portugal 23. Romania 24. Slovakia 25. Slovenia 26. Spain 27. Sweden www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The EU27: Internal Politics and Views on Brexit Contents Summary 6 1. Austria 13 1.1 Key Facts 13 1.2 Background 14 1.3 Current Government and Recent Political Developments 15 1.4 Views on Brexit 17 2. Belgium 25 2.1 Key Facts 25 2.2 Background 25 2.3 Current Government and recent political developments 26 2.4 Views on Brexit 28 3. Bulgaria 32 3.1 Key Facts 32 3.2 Background 32 3.3 Current Government and recent political developments 33 3.4 Views on Brexit 35 4. Croatia 37 4.1 Key Facts 37 4.2 Background 37 4.3 Current Government and recent political developments 38 4.4 Views on Brexit 39 5. Cyprus 42 5.1 Key Facts 42 5.2 Background 42 5.3 Current Government and recent political developments 43 5.4 Views on Brexit 45 6. Czech Republic 49 6.1 Key Facts 49 6.2 Background 49 6.3 Current Government and recent political developments 50 6.4 Views on Brexit 53 7. -

List of Participants

List of Participants Title Last Name Fist name Company Function Ms ABBAS RASHO KHALAF Farida Yazda Ms ABRAMOVA Iuliana WAVE Member of Advisory Board Ms ABRASHEVA Desislava Ministry of Justice of Bulgaria Head of the Cabinet of the Minister of Justice Ms ACAR Ayse Feride Council of Europe President of GREVIO ACCARDO Nicola European Commission Ms ACH Coline European Parliament Parliamentary assistant Ms ADAMO Chiara European Commission Head of Unit "Fundamental Rights Policy" Ms AGAPIOU JOSEPHIDES Kalliope Chair, Management Board Ms AGHATISE Esohe Associazione IROKO Onlus Executive Director Mr AGOTHA Anthony European Commission Member of Cabinet First Vice-President Ms AHER Kaidi Office of the President Head of the Communication Department Ms AHLADOVA Desislava Ministry of Justice of Bulgaria Deputy Minister of Justice Ms AHMED Ifrah Ifrah Foundation Director Ms AITTONIEMI Eeva Ministry of Justice Ministerial adviser Mr ALATOPOULOS Filippos - Kyriakos European Parliament Temporary Official / Vice-Presidents' Secretariat Ms ALBU Laura European Women's Lobby Member Executive Committee Mr ALBUQUERQUE Daniel European Commission Ms ALTINISIK Serap European Women's Lobby Programme Director AMIRAN Pirumashvili Georgian Public Broadcasting Ms ANDRAŠEK Valentina Women Against Violence Europe Country Delegate Mrs ANDRASSY Irena European Commission Ms ANDRIEUX Isabelle ING Mr ANGELOPOULOS Georgios Ms ANITA Sarkeesian Feminist Frequency Mrs ANTANOVIČA Agnija LETA Journalist Social Issues Ms AREVALO CASAS Sara EDF Personal Assistant Mrs ARRILLAGA Ana -

Nordic Health Care Systems Pb:Nordic Health Care Systems Pb 11/8/09 14:04 Page 1

Nordic Health Care Systems pb:Nordic Health Care Systems pb 11/8/09 14:04 Page 1 Nordic Health Care Systems Recent Reforms and Current Policy Challenges European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series “The book is very valuable as actual information about the health systems in the Nordic countries and the changes that have been made during the last two decades. It informs well both about the similarities within the ‘Nordic Health Model’ and the important differences that exist between the countries.” Bo Könberg, County Governor, Former Minister of Health and Social Insurance in Sweden (1991-1994) “The publishing of this book about the Nordic health care systems is a major Nordic Health Care Systems event for those interested not only in Nordic health policy and health systems but also for everybody interested in comparative health policy and health systems. It is the first book in its kind. It covers the four “large” Nordic countries, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland, and does so in a very systematically comparative way. The book is well organized, covers “everything” and is analytically sophisticated.” Ole Berg, Professor of Health Management, University of Oslo This book examines recent patterns of health reform in Nordic health care systems, and the balance between stability and change in how these systems have developed. Nordic Health Care Systems The health systems in Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Finland are investigated through detailed comparisons along a variety of policy-driven parameters. The following themes are explored: Recent Reforms and Current Policy Challenges • Politicians, patients, and professions Financing, production, and distribution • &Saltman Magnussen,Vrangbaek • The role of the primary health sector • The role of public health • Internal management mechanisms • Impact of the European Union The book probes the impact of these topics and then contrasts the development across all four coumntries, allowing the reader to gain a sense of perspective both on the individual systems as well as on the region as a whole. -

Investor Presentation May 2021 SEK Is to Strengthen the Mission Competitiveness of the Swedish Export Industry and Create Employment and Sustainable Growth in Sweden

Investor presentation May 2021 SEK is to strengthen the Mission competitiveness of the Swedish export industry and create employment and sustainable growth in Sweden. A sustainable world through Vision increased Swedish export. 2 100% Owned by the Swedish Government Kingdom of Sweden Population 10 million Surface 450 000 km2 Capital Stockholm Language Swedish, English widely spoken Political system Parliamentary democracy European status Inside EU, outside Euro Currency Swedish Krona 4 % Public Debt to GDP 250 Economy of Sweden 200 150 Rating AAA/Aaa/Aaa 100 GDP Growth Q4 2020 (QoQ/YoY) -0.2% / -2.2% 50 GDP Growth 2020 -2.8% 0 GDP 2020 USD 538 bn* Japan Italy USA GDP per capita 2020 USD 51 950* France Germany Sweden Unemployment March 2021 9.5%** bps 5 year CDS spreads CPI/CPIF*** March 2021 (YoY) 1.7% / 1.9% 200 Repo Rate April 2021 0% 150 100 * USD/SEK average 2020, 9.20 ** Seasonally adjusted, % of labour force 50 *** CPIF = CPI with fixed mortgage rates 0 Source: Bloomberg, IMF, SCB 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Sweden Italy France 5 Germany Japan USA Swedish Exports Large part of GDP and well diversified Key export goods Exports and Imports % Share of GDP 55 Materials 18% 50 Consumer goods 16% 45 Machinery 15% Auto 14% 40 IT & telecom 11% 35 Pulp & paper 10% 30 Health care 8% 25 Energy 5% Construction 3% Export Import Source: SCB as of December 31, 2020 6 Swedish exporters SEK has a complementary role in the market . Our offering provides a complement to bank and capital market finance for exporters that want a range of different financing sources. -

Prosperity and Sustainability – Local Cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region

AUGUST 16–18, 2006 Summary of the conference in Visby Prosperity and Sustainability – Local Cooperation in the Baltic Sea Region Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................... 3 Theme 1: Strengthening Cooperation between Local, National and European Actors in the Baltic Sea Region ....................................................... 4 Experiences from Three Different Border Regions ... 9 Theme 2: Providing a Secure and Sustainable Livelihood in the Baltic Sea Region – Environment and Energy ......................................................11 Panel Debate Concerning the Combating of Trafficking ......................................................15 Theme 3: Promoting Trade and Investment in the Baltic Sea Region .............................................18 Conclusions: Challenges for Further Development of Regional Cooperation in the Baltic Sea Area .... 22 This document has been performed by Sida’s Baltic Sea Unit, commissioned by the Swedish Prime Minister’s office. The texts have been written by Josefin Dahlander (Sida), Marie Sandberg (The Institute for Local and Regional Democracy, Växjö) and Tor-Björn Åstrand Karlsson (The Institute for Local and Regional Democracy, Växjö). Josefin Dahlander is responsible for the content of the publication. Published by Sida 2006 Baltic Sea Unit Printed by Edita Communication AB, 2006 Articlenumber: SIDA31159en This publication can be downloaded/ordered from www.sida.se/publications Introduction The conference ’Prosperity and sustainability – local cooperation in the Baltic Sea region‘ was arranged by the Swedish Government on the 16–18th of August 2006 in Visby. The Swedish Prime Minister invited leaders of local and regional institutions in Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, Iceland, Norway, Ukraine and Belarus to participate in the event. The civil society, business communities and strategic partners at national, international and European levels were also represented among the participants. -

Developing Sustainable Cities in Sweden

DEVELOPING SUSTAINABLE CITIES IN SWEDEN ABOUT THE BOOKLET This booklet has been developed within the Sida-funded ITP-programme: »Towards Sustainable Development and Local Democracy through the SymbioCity Approach« through the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR ), SKL International and the Swedish International Centre for Democracy (ICLD ). The purpose of the booklet is to introduce the reader to Sweden and Swedish experiences in the field of sustainable urban development, with special emphasis on regional and local government levels. Starting with a brief historical exposition of the development of the Swedish welfare state and introducing democracy and national government in Sweden of today, the main focus of the booklet is on sustainable planning from a local governance perspective. The booklet also presents practical examples and case studies from different municipalities in Sweden. These examples are often unique, and show the broad spectrum of approaches and innovative solutions being applied across the country. EDITORIAL NOTES MANUSCRIPT Gunnar Andersson, Bengt Carlson, Sixten Larsson, Ordbildarna AB GRAPHIC DESIGN AND ILLUSTRATIONS Viera Larsson, Ordbidarna AB ENGLISH EDITING John Roux, Ordbildarna AB EDITORIAL SUPPORT Anki Dellnäs, ICLD, and Paul Dixelius, Klas Groth, Lena Nilsson, SKL International PHOTOS WHEN NOT STATED Gunnar Andersson, Bengt Carlsson, Sixten Larsson, Viera Larsson COVER PHOTOS Anders Berg, Vattenfall image bank, Sixten Larsson, SKL © Copyright for the final product is shared by ICLD and SKL International, 2011 CONTACT INFORMATION ICLD, Visby, Sweden WEBSITE www.icld.se E-MAIL [email protected] PHONE +46 498 29 91 80 SKL International, Stockholm, Sweden WEBSITE www.sklinternational.se E-MAIL [email protected] PHONE +46 8 452 70 00 ISBN 978-91-633-9773-8 CONTENTS 1. -

2013 AGM Powerpoint

AGENDA 1. Welcome note & member status 2. Sportaccord membership 3. Confirmation of finances and minutes AGM 2012 4. Report of the FIR Council 2013 5. Financial report 2013, preview 2014 6. Members report 2013 7. Council preview 2014 8. Requests by FIR members and FIR Council 9. Any other business 1. WELCOME NOTE Confirmation President and Country Representatives 42 members, 5 new countries in 2013 (in red) 1. Armenia, 1 16. Greece, 1 31. Pakistan, 1 2. Australia, 1 17. Hong Kong – China, 1 32. Poland, 2 3. Austria, 6 18. Hungary, 3 33. Romania, 1 4. Belgium, 4 19. India, 1 34. Russia, 1 5. Brazil, 1 20. Iraq, 1 35. Scotland, 1 6. Bulgaria, 2 21. Ireland, 1 36. Slovakia, 1 7. Canada, 3 22. Israel, 1 37. Slovenia, 1 8. Croatia, 1 23. Italy, 2 38. South Africa, 1 9. Czech Republic, 3 24. Latvia, 1 39. Sweden, 6 10. Denmark, 2 25. Liechtenstein, 1 40. Switzerland, 6 11. England, 6 26. F.Y.R.O. Macedonia, 1 41. Turkey, 1 12. Estonia, 1 27. Malaysia, 1 42. USA, 1 13. Finland, 4 28. Mongolia, 1 Total 85 votes (>50% = 43 ) 14. France, 2 29. Netherlands, 2 15. Germany, 6 30. New Zealand, 1 1.2 POTENTIAL NEW MEMBERS o Bangladesh, Manoranjan Mishra has visited them o China, first contacts o Egypt, Karim Hanna is in contact o Lebanon, Marc Mourad has played on World Tour o Luxemburg, Tony Nightingale has played World Champs o Iceland, Anbor Jon Porbarsson first contacts o Japan, Hiron first Japanese player ever at English Open o Nepal, Manoranjan Mishra is in contact o Norway, Lennart Eklundh in Squash contact o Portugal, Still hoping for Jacob de Vries/Luis Barbossa o Qatar, Alexandra Rosca has played on World Tour o Serbia, Puzant Kassabian in contact o Ukraine, Aija Klaseva first contacts o Zimbabwe, Jessica Calder first contacts through Patric Kalous o Malta, Duncan Stahl o Morocco, Ahmad Bahadli Why is FIR membership so important? From 2014 players from non-fir members may not play on the FIR World Tour in ANY DRAWS! 2 .