Testimony of Ralph Mcnutt 4 October 2017.Rev2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARS an Overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera Science

MARS MARS INFORMATICS The International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration Open Access Journals Science An overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera science investigation Michael C. Malin1, Kenneth S. Edgett1, Bruce A. Cantor1, Michael A. Caplinger1, G. Edward Danielson2, Elsa H. Jensen1, Michael A. Ravine1, Jennifer L. Sandoval1, and Kimberley D. Supulver1 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA, 92191-0148, USA; 2Deceased, 10 December 2005 Citation: Mars 5, 1-60, 2010; doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0001 History: Submitted: August 5, 2009; Reviewed: October 18, 2009; Accepted: November 15, 2009; Published: January 6, 2010 Editor: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University Reviewers: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University; R. Aileen Yingst, University of Wisconsin Green Bay Open Access: Copyright 2010 Malin Space Science Systems. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: NASA selected the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) investigation in 1986 for the Mars Observer mission. The MOC consisted of three elements which shared a common package: a narrow angle camera designed to obtain images with a spatial resolution as high as 1.4 m per pixel from orbit, and two wide angle cameras (one with a red filter, the other blue) for daily global imaging to observe meteorological events, geodesy, and provide context for the narrow angle images. Following the loss of Mars Observer in August 1993, a second MOC was built from flight spare hardware and launched aboard Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in November 1996. -

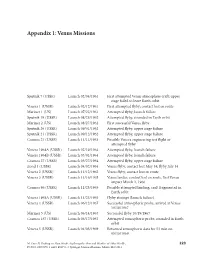

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Glossary of Acronyms and Definitions

CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2018 CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 1 Glossary of Acronyms and Definitions A A/D Analog-to-Digital AACS Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem AAN Automatic Alarm Notification AB Approved By ABS timed Absolute Timed AC Acoustics AC Alternating Current ACC Accelerometer ACCE Accelerometer Electronics ACCH Accelerometer Head ACE Aerospace Communications & Information Expertise ACE Aerospace Control Environment ACE Air Coordination Element ACE Attitude Control Electronics ACI Accelerometer Interface ACME Antenna Calibration and Measurement Equipment ACP Aerosol Collector Pyrolyzer ACS Attitude Control Subsystem ACT Actuator ACT Automated Command Tracker ACTS Advanced Communications Technology Satellite AD Applicable Document ADAS AWVR Data Acquisition Software ADC Analog-to-Digital Converter ADP Automatic Data Processing AE Activation Energy AEB Agência Espacial Brasileira (Brazilian Space Agency) AF Air Force AFC AACS Flight Computer AFETR Air Force Eastern Test Range AFETRM Air Force Eastern Test Range Manual 2 CASSINI FINAL MISSION REPORT 2019 AFS Atomic Frequency Standard AFT Abbreviated Functional Test AFT Allowable Flight Temperature AFS Andrew File System AGC Automatic Gain Control AGU American Geophysical Union AHSE Assembly, Handling, & Support Equipment AIT Assembly, Integration & Test AIV Assembly, Integration & Verification AKR Auroral Kilometric Radiation AL Agreement Letter AL Aluminum AL Anomalously Large ALAP As Low As Practical ALARA As Low As Reasonably Achievable ALB Automated Link -

+ New Horizons

Media Contacts NASA Headquarters Policy/Program Management Dwayne Brown New Horizons Nuclear Safety (202) 358-1726 [email protected] The Johns Hopkins University Mission Management Applied Physics Laboratory Spacecraft Operations Michael Buckley (240) 228-7536 or (443) 778-7536 [email protected] Southwest Research Institute Principal Investigator Institution Maria Martinez (210) 522-3305 [email protected] NASA Kennedy Space Center Launch Operations George Diller (321) 867-2468 [email protected] Lockheed Martin Space Systems Launch Vehicle Julie Andrews (321) 853-1567 [email protected] International Launch Services Launch Vehicle Fran Slimmer (571) 633-7462 [email protected] NEW HORIZONS Table of Contents Media Services Information ................................................................................................ 2 Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................. 3 Pluto at a Glance ...................................................................................................................... 5 Why Pluto and the Kuiper Belt? The Science of New Horizons ............................... 7 NASA’s New Frontiers Program ........................................................................................14 The Spacecraft ........................................................................................................................15 Science Payload ...............................................................................................................16 -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

Gao-21-306, Nasa

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees May 2021 NASA Assessments of Major Projects GAO-21-306 May 2021 NASA Assessments of Major Projects Highlights of GAO-21-306, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found This report provides a snapshot of how The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) portfolio of major well NASA is planning and executing projects in the development stage of the acquisition process continues to its major projects, which are those with experience cost increases and schedule delays. This marks the fifth year in a row costs of over $250 million. NASA plans that cumulative cost and schedule performance deteriorated (see figure). The to invest at least $69 billion in its major cumulative cost growth is currently $9.6 billion, driven by nine projects; however, projects to continue exploring Earth $7.1 billion of this cost growth stems from two projects—the James Webb Space and the solar system. Telescope and the Space Launch System. These two projects account for about Congressional conferees included a half of the cumulative schedule delays. The portfolio also continues to grow, with provision for GAO to prepare status more projects expected to reach development in the next year. reports on selected large-scale NASA programs, projects, and activities. This Cumulative Cost and Schedule Performance for NASA’s Major Projects in Development is GAO’s 13th annual assessment. This report assesses (1) the cost and schedule performance of NASA’s major projects, including the effects of COVID-19; and (2) the development and maturity of technologies and progress in achieving design stability. -

Planned Observations of the Diffuse Sky Radiation During Shuttle Mission Sts-4

PLANNED OBSERVATIONS OF THE DIFFUSE SKY RADIATION DURING SHUTTLE MISSION STS-4 J.L. Weinberg, R.C. Hahn, F. Giovane, and D.W. Schuerman Space Astronomy Laboratory State University of N. Y. at Albany Albany, N. Y. 12203 ABSTRACT The Skylab flight spare 10-color photopolarimeter (Weinberg, et al. _, 1975; Sparrow, et al.^ 1977) is being refurbished for use in Space Shuttle mission STS-4, a test flight currently scheduled for October 1980. Obser vations will be made of zodiacal light, background starlight, and the Shuttle-induced atmosphere (spacecraft corona), with emphasis on regions of sky closer than 90° to the sun. A ten color (near UV to near IR) photopolarimeter was used during Skylab missions SL-2 and SL-3 to measure diffuse sky brightness and polar ization associated with zodiacal light, background starlight, and space craft corona (Weinberg, et aL.y 1975; Sparrow, et dl.3 1977). The photo polarimeter and boresighted 16 mm camera (Fig. 1) were attached to an alt-azimuth mounting which was part of an astronaut-operated facility which could deploy an instrument out to a distance of 5.5 m beyond the Skylab orbital workshop using scientific airlocks (SAL's) in either the solar or antisolar di rection (Henize and Weinberg, 1973). The instrument was designed to make fixed-position or sky-scanning measurements during spacecraft day or night, including mapping the entire sky to within 15° of the sun. Unfor tunately, the solar SAL could not be used because a heat shield (parasol) Fig. 1. The Skylab photopolarimeter and was permanently deployed camera and their sunshields. -

Planetary Exploration : Progress and Promise

PLANET ARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENTS: NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS: SIGNIFICANT EVENTS PLANETARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS-1978 NASA SPACE SCIENCE PROGRAM FUNDING: 5 -YEAR PLAN NASA OSS 5-YEAR PLAN: PLANETARY PROGRAM FUNDING REFERENCE COP'I PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist Lunar and Planetary Institute 3303 NASA Road One Houston, Texas 77058 Lunar and Planetary Institute Contribution No. 297 (June 1978 update> NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS SIGNIFICANT EVENTS MISSION EVENTS PIONEER VENUS ORBITER ORBIT INSERTION, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER VENUS MULTIPROBE VENUS ENCOUNTER/ENTRY, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER 11 SATURN ENCOUNTER, SEPTEMBER 1979 VOYAGER 1 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, MARCH 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1980 VOYAGER 2 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, JULY 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, AUGUST 1981 URANUS ENCOUNTER, JANUARY 1986 SOLAR MAXIMUM MISSION LAUNCH, OCTOBER 1979 VENUS ORBITAL IMAGING RADAR VENUS ENCOUNTER, SPRING 1985 SOLAR POLAR MISSION JUPITER ENCOUNTER, 1984 SOLAR POLES PASSAGE, 1986 GALILEO MISSION MARS FLYBY, APRIL 1982 JUPITER ENCOUNTER (ORBIT INSERTION/ PROBE ENTRY), 1985 COMET HALLEYlTEMPEL, . 2'J MISSION• HALLEY ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1985 TEMPEL 2 ENCOUNTER, JULY 1988 or COMET ENCKE RENDEZVOUS ENCKE ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS GEOCHEMICAL ORBITER MARS ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS SAMPLE RETURN MARS ENCOUNTER, 1989 EARTH RETURN, 1991 SATURN ORBITER DUAL PROBE SATURN ENCOUNTER, 1992 from NASA Headquarters 5-year plan May 1978 PLANETARY EXPLORATION -- PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENT S: Planetary exploration progress - 1977 fig. 1 The future fig. 2 Inner planets plan fig. 3 Outer planets plan fig. 4 Small bodies plan fig. 5 compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE 3303 NASA Road One Houston, TX 77058 September 1977 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE CONTRIBUTION No. -

Calwater Field Studies Designed to Quantify the Roles of Atmospheric Rivers and Aerosols in Modulating U.S

CALWATER FIELD STUDIES DESIGNED TO QUANTIFY THE ROLES OF ATMOSPHERIC RIVERS AND AEROSOLS IN MODULATING U.S. WEST COAST PRECIPITATION IN A CHANGING CLIMATE BY F. M. RALPH, K. A. PRATHER, D. CAYAN, J. R. SPAckmAN, P. DEMOTT, M. DETTINGER, C. FAIRALL, R. LEUNG, D. ROSENFELD, S. RUTLEDGE, D. WALISER, A. B. WHITE, J. COrdEIRA, A. MARTIN, J. HELLY, AND J. INTRIERI A group of meteorologists, hydrologists, climate scientists, atmospheric chemists, and oceanographers have created an interdisciplinary research effort to explore the causes of variability of rainfall, flooding and water supply along the U.S. West Coast. alWater is a multiyear program of field cam- air pollution, aerosol chemistry, and climate. The paigns, numerical modeling experiments, and purpose of the CalWater workshop was threefold: 1) to C scientific analysis focused on phenomena that discuss key science gaps and the potential for lever- are key to the water supply and associated extremes aging long-term Hydrometeorology Testbed (HMT) (drought, flood) in the U.S. West Coast region. Table 1 data collection in California (Ralph et al. 2013), 2) to summarizes CalWater’s development timeline. The explore interest in the potential impacts of anthropo- results from CalWater are also relevant in many genic aerosols on California’s water supply, and 3) to other regions around the globe. CalWater began as build on the Suppression of Precipitation (SUPRECIP) a workshop at Scripps Institution of Oceanography experiment from 2005 to 2007 (Rosenfeld et al. 2008b) (SIO) in 2008 that brought -

Pioneer Anomaly: What Can We Learn from Future Planetary Exploration Missions?

56th International Astronautical Congress, Paper IAC-05-A3.4.02 PIONEER ANOMALY: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM FUTURE PLANETARY EXPLORATION MISSIONS? Andreas Rathke EADS Astrium GmbH, Dept. AED41, 88039 Friedrichshafen, Germany. Email: [email protected] Dario Izzo ESA Advanced Concepts Team, ESTEC, Keplerlaan 1, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] The Doppler-tracking data of the Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft show an unmodelled constant acceleration in the direction of the inner Solar System. Serious efforts have been undertaken to find a conventional explanation for this effect, all without success at the time of writing. Hence the effect, commonly dubbed the Pioneer anomaly, is attracting considerable attention. Unfortunately, no other space mission has reached the long-term navigation accuracy to yield an independent test of the effect. To fill this gap we discuss strategies for an experimental verification of the anomaly via an upcoming space mission. Emphasis is put on two plausible scenarios: non-dedicated concepts employing either a planetary exploration mission to the outer Solar System or a piggybacked micro- spacecraft to be launched from an exploration spacecraft travelling to Saturn or Jupiter. The study analyses the impact of a Pioneer anomaly test on the system and trajectory design for these two paradigms. Both paradigms are capable of verifying the Pioneer anomaly and determine its magnitude at 10% level. Moreover they can discriminate between the most plausible classes of models of the anomaly. The necessary adaptions of the system and mission design do not impair the planetary exploration goals of the missions. I. -

Titan a Moon with an Atmosphere

TITAN A MOON WITH AN ATMOSPHERE Ashley Gilliam Earth 450 – Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn 4/29/13 SATURN HAS > 60 SATELLITES, WHY TITAN? Is the only satellite with a dense atmosphere Has a nitrogen-rich atmosphere resembles Earth’s Is the only world besides Earth with a liquid on its surface • Possible habitable world Based on its size… Titan " a planet in its o# $ght! R = 6371 km R = 2576 km R = 1737 km Ch$%iaan Huy&ns (1629-1695) DISCOVERY OF TITAN Around 1650, Huygens began building telescopes with his brother Constantijn On March 25, 1655 Huygens discovered Titan in an attempt to study Saturn’s rings Named the moon Saturni Luna (“Saturns Moon”) Not properly named until the mid-1800’s THE DISCOVERY OF TITAN’S ATMOSPHERE Not much more was learned about Titan until the early 20th century In 1903, Catalan astronomer José Comas Solà claimed to have observed limb darkening on Titan, which requires the presence of an atmosphere Gerard P. Kuiper (1905-1973) José Comas Solà (1868-1937) This was confirmed by Gerard Kuiper in 1944 Image Credit: Ralph Lorenz Voyager 1 Launched September 5, 1977 M"sions to Titan Pioneer 11 Launched April 6, 1973 Cassini-Huygens Images: NASA Launched October 15, 1997 Pioneer 11 Could not penetrate Titan’s Atmosphere! Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 What did we learn about the Atmosphere? • Composition (N2, CH4, & H2) • Variation with latitude (homogeneously mixed) • Temperature profile Mesosphere • Pressure profile Stratosphere Troposphere Image Credit: Fulchignoni, et al., 2005 Image Credit: Conway et al. -

DAVINCI: Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Lori S

DAVINCI: Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Lori S. Glaze, James B. Garvin, Brent Robertson, Natasha M. Johnson, Michael J. Amato, Jessica Thompson, Colby Goodloe, Dave Everett and the DAVINCI Team NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 690 8800 Greenbelt Road Greenbelt, MD 20771 301-614-6466 Lori.S.Glaze@ nasa.gov Abstract—DAVINCI is one of five Discovery-class missions questions as framed by the NRC Planetary Decadal Survey selected by NASA in October 2015 for Phase A studies. and VEXAG, without the need to repeat them in future New Launching in November 2021 and arriving at Venus in June of Frontiers or other Venus missions. 2023, DAVINCI would be the first U.S. entry probe to target Venus’ atmosphere in 45 years. DAVINCI is designed to study The three major DAVINCI science objectives are: the chemical and isotopic composition of a complete cross- section of Venus’ atmosphere at a level of detail that has not • Atmospheric origin and evolution: Understand the been possible on earlier missions and to image the surface at origin of the Venus atmosphere, how it has evolved, optical wavelengths and process-relevant scales. and how and why it is different from the atmospheres of Earth and Mars. TABLE OF CONTENTS • Atmospheric composition and surface interaction: Understand the history of water on Venus and the 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1 chemical processes at work in the lower atmosphere. 2. MISSION DESIGN ..................................................... 2 • Surface properties: Provide insights into tectonic, 3. PAYLOAD ................................................................. 2 volcanic, and weathering history of a typical tessera 4. SUMMARY ................................................................ 3 (highlands) terrain.