Pioneer Anomaly: What Can We Learn from Future Planetary Exploration Missions?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

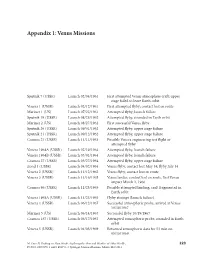

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

+ New Horizons

Media Contacts NASA Headquarters Policy/Program Management Dwayne Brown New Horizons Nuclear Safety (202) 358-1726 [email protected] The Johns Hopkins University Mission Management Applied Physics Laboratory Spacecraft Operations Michael Buckley (240) 228-7536 or (443) 778-7536 [email protected] Southwest Research Institute Principal Investigator Institution Maria Martinez (210) 522-3305 [email protected] NASA Kennedy Space Center Launch Operations George Diller (321) 867-2468 [email protected] Lockheed Martin Space Systems Launch Vehicle Julie Andrews (321) 853-1567 [email protected] International Launch Services Launch Vehicle Fran Slimmer (571) 633-7462 [email protected] NEW HORIZONS Table of Contents Media Services Information ................................................................................................ 2 Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................. 3 Pluto at a Glance ...................................................................................................................... 5 Why Pluto and the Kuiper Belt? The Science of New Horizons ............................... 7 NASA’s New Frontiers Program ........................................................................................14 The Spacecraft ........................................................................................................................15 Science Payload ...............................................................................................................16 -

The Quest to Understand the Pioneer Anomaly

The quest to understand the Pioneer anomaly I Michael Martin Nieto, Theoretical Division (MS-8285) Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alarnos, New Mexico 87545 USA E-mail: [email protected] +a l1 l I l uring the 1960's, when the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Pioneer 10 was launched on 2 March 1972 local time, aboard D first started thinking about what eventually became the an Atlas/Centaur/TE364-4launch vehicle (see Fig. l).It was the "Grand Tours" of the outer planets (the Voyager missions of the first craft launched into deep space and was the first to reach an 1970's and 1980's),the use of planetary flybys for gravity assists of outer giant planet, Jupiter,on 4 Dec. 1973 [l, 21. Later it was the first spacecraft became of great interest. The concept was to use flybys to leave the "solar system" (past the orbit of Pluto or, should we now of the major planets to both mowthe direction of the spacecraft say, Neptune). The Pioneer project, eventually extending over and also to add to its heliocentric velocity in a manner that was decades, was managed at NASAIAMES Research Center under the unfeasible using only chemical fuels. The first time these ideas were hands of four successive project managers, the legendary Charlie put into practice in deep space was with the Pioneers. Hall, Richard Fimrnel, Fred Wirth, and the current Larry Lasher. While in its Earth-Jupiter cruise, Pioneer 10 was still bound to the solar system. By 9 January 1973 Pjoneer l0 was at a distance of 3.40 AU (Astronomical Units'), beyond the asteroid belt. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

Planetary Exploration : Progress and Promise

PLANET ARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENTS: NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS: SIGNIFICANT EVENTS PLANETARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS-1978 NASA SPACE SCIENCE PROGRAM FUNDING: 5 -YEAR PLAN NASA OSS 5-YEAR PLAN: PLANETARY PROGRAM FUNDING REFERENCE COP'I PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist Lunar and Planetary Institute 3303 NASA Road One Houston, Texas 77058 Lunar and Planetary Institute Contribution No. 297 (June 1978 update> NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS SIGNIFICANT EVENTS MISSION EVENTS PIONEER VENUS ORBITER ORBIT INSERTION, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER VENUS MULTIPROBE VENUS ENCOUNTER/ENTRY, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER 11 SATURN ENCOUNTER, SEPTEMBER 1979 VOYAGER 1 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, MARCH 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1980 VOYAGER 2 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, JULY 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, AUGUST 1981 URANUS ENCOUNTER, JANUARY 1986 SOLAR MAXIMUM MISSION LAUNCH, OCTOBER 1979 VENUS ORBITAL IMAGING RADAR VENUS ENCOUNTER, SPRING 1985 SOLAR POLAR MISSION JUPITER ENCOUNTER, 1984 SOLAR POLES PASSAGE, 1986 GALILEO MISSION MARS FLYBY, APRIL 1982 JUPITER ENCOUNTER (ORBIT INSERTION/ PROBE ENTRY), 1985 COMET HALLEYlTEMPEL, . 2'J MISSION• HALLEY ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1985 TEMPEL 2 ENCOUNTER, JULY 1988 or COMET ENCKE RENDEZVOUS ENCKE ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS GEOCHEMICAL ORBITER MARS ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS SAMPLE RETURN MARS ENCOUNTER, 1989 EARTH RETURN, 1991 SATURN ORBITER DUAL PROBE SATURN ENCOUNTER, 1992 from NASA Headquarters 5-year plan May 1978 PLANETARY EXPLORATION -- PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENT S: Planetary exploration progress - 1977 fig. 1 The future fig. 2 Inner planets plan fig. 3 Outer planets plan fig. 4 Small bodies plan fig. 5 compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE 3303 NASA Road One Houston, TX 77058 September 1977 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE CONTRIBUTION No. -

NASA and Planetary Exploration

**EU5 Chap 2(263-300) 2/20/03 1:16 PM Page 263 Chapter Two NASA and Planetary Exploration by Amy Paige Snyder Prelude to NASA’s Planetary Exploration Program Four and a half billion years ago, a rotating cloud of gaseous and dusty material on the fringes of the Milky Way galaxy flattened into a disk, forming a star from the inner- most matter. Collisions among dust particles orbiting the newly-formed star, which humans call the Sun, formed kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals which in turn aggregated to form the present-day planets.1 On the third planet from the Sun, several billions of years of evolution gave rise to a species of living beings equipped with the intel- lectual capacity to speculate about the nature of the heavens above them. Long before the era of interplanetary travel using robotic spacecraft, Greeks observing the night skies with their eyes alone noticed that five objects above failed to move with the other pinpoints of light, and thus named them planets, for “wan- derers.”2 For the next six thousand years, humans living in regions of the Mediterranean and Europe strove to make sense of the physical characteristics of the enigmatic planets.3 Building on the work of the Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Hellenistic Greeks who had developed mathematical methods to predict planetary motion, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria put forth a theory in the second century A.D. that the planets moved in small circles, or epicycles, around a larger circle centered on Earth.4 Only partially explaining the planets’ motions, this theory dominated until Nicolaus Copernicus of present-day Poland became dissatisfied with the inadequacies of epicycle theory in the mid-sixteenth century; a more logical explanation of the observed motions, he found, was to consider the Sun the pivot of planetary orbits.5 1. -

NASA Ames Research Center Intelligent Systems and High End Computing

NASA Ames Research Center Intelligent Systems and High End Computing Dr. Eugene Tu, Director NASA Ames Research Center Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000 A 80-year Journey 1960 Soviet Union United States Russia Japan ESA India 2020 Illustration by: Bryan Christie Design Updated: 2015 Protecting our Planet, Exploring the Universe Earth Heliophysics Planetary Astrophysics Launch missions such as JWST to Advance knowledge unravel the of Earth as a Determine the mysteries of the system to meet the content, origin, and universe, explore challenges of Understand the sun evolution of the how it began and environmental and its interactions solar system and evolved, and search change and to with Earth and the the potential for life for life on planets improve life on solar system. elsewhere around other stars earth “NASA Is With You When You Fly” Safe, Transition Efficient to Low- Growth in Carbon Global Propulsion Operations Innovation in Real-Time Commercial System- Supersonic Wide Aircraft Safety Assurance Assured Ultra-Efficient Autonomy for Commercial Aviation Vehicles Transformation NASA Centers and Installations Goddard Institute for Space Studies Plum Brook Glenn Research Station Independent Center Verification and Ames Validation Facility Research Center Goddard Space Flight Center Headquarters Jet Propulsion Wallops Laboratory Flight Facility Armstrong Flight Research Center Langley Research White Sands Center Test Facility Stennis Marshall Space Kennedy Johnson Space Space Michoud Flight Center Space Center Center Assembly Center Facility -

Max-Planck-Institut Für Sonnensystemforschung Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research Tätigkeitsbericht 2011 Activit

Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research Tätigkeitsbericht 2011 Activity Report 2011 Inhalt Contents 1 Inhalt Contents 1 Wissenschaftliche Zusammenarbeit 2 Scientific collaborations 1.1 Wissenschaftliche Gäste 2 Scientific guests 1.2 Aufenthalt von MPS-Wissenschaftlern an anderen Instituten 4 Stay of MPS scientists at other institutes 1.3 Projekte in Zusammenarbeit mit anderen Institutionen 5 Projects in collaboration with other institutions 2 Vorschläge und Anträge 22 Proposals 2.1 Projektvorschläge 22 Project proposals 2.2 Anträge auf Beobachtungszeit 23 Observing time proposals 3 Publikationen 25 Publications 3.1 Referierte Publikationen 25 Refereed publications 3.2 Doktorarbeiten 45 PhD theses 4 Vorträge und Poster 46 Talks and posters 5 Seminare 69 Seminars 6 Lehrtätigkeit 73 Lectures 7 Tagungen und Workshops 74 Conferences and workshops 7.1 Organisation von Tagungen und Workshops 74 Organization of conferences and workshops 7.2 Convener bei wissenschaftlichen Tagungen 74 Convener during scientific meetings 8 Gutachtertätigkeit für wissenschaftliche Zeitschriften 75 Reviews for scientific journals 9 Herausgebertätigkeit 76 Editorship 10 Mitgliedschaft in wissenschaftlichen Gremien 76 Membership in scientific councils 11 Auszeichnungen 77 Awards Wissenschaftliche Zusammenarbeit / Scientific collaborations 2 1. Wissenschaftliche Zusammenarbeit / Scientific collaborations 1.1 Wissenschaftlich Gäste (mit Aufenthalt ≥1 Woche) Scientific guests (with stay ≥1 week) Jaime Araneda (University of Concepcion, Chile), 1 Jul - 15 Aug (host: E. Marsch) Ankit Barik (Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpour, India), 19 May - 15 Jul (host: U. Christensen) Alexander Bazilevsky (Vernadsky Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia), 1 Aug - 26 Aug (host: W. Markiewicz) Jishnu Bhattacharya (Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India), 10 May – 18 Jul (host: L. -

Titan a Moon with an Atmosphere

TITAN A MOON WITH AN ATMOSPHERE Ashley Gilliam Earth 450 – Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn 4/29/13 SATURN HAS > 60 SATELLITES, WHY TITAN? Is the only satellite with a dense atmosphere Has a nitrogen-rich atmosphere resembles Earth’s Is the only world besides Earth with a liquid on its surface • Possible habitable world Based on its size… Titan " a planet in its o# $ght! R = 6371 km R = 2576 km R = 1737 km Ch$%iaan Huy&ns (1629-1695) DISCOVERY OF TITAN Around 1650, Huygens began building telescopes with his brother Constantijn On March 25, 1655 Huygens discovered Titan in an attempt to study Saturn’s rings Named the moon Saturni Luna (“Saturns Moon”) Not properly named until the mid-1800’s THE DISCOVERY OF TITAN’S ATMOSPHERE Not much more was learned about Titan until the early 20th century In 1903, Catalan astronomer José Comas Solà claimed to have observed limb darkening on Titan, which requires the presence of an atmosphere Gerard P. Kuiper (1905-1973) José Comas Solà (1868-1937) This was confirmed by Gerard Kuiper in 1944 Image Credit: Ralph Lorenz Voyager 1 Launched September 5, 1977 M"sions to Titan Pioneer 11 Launched April 6, 1973 Cassini-Huygens Images: NASA Launched October 15, 1997 Pioneer 11 Could not penetrate Titan’s Atmosphere! Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 Image Credit: NASA Vo y a &r 1 What did we learn about the Atmosphere? • Composition (N2, CH4, & H2) • Variation with latitude (homogeneously mixed) • Temperature profile Mesosphere • Pressure profile Stratosphere Troposphere Image Credit: Fulchignoni, et al., 2005 Image Credit: Conway et al. -

NASA History Fact Sheet

NASA History Fact Sheet National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Policy and Plans NASA History Office NASA History Fact Sheet A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION by Stephen J. Garber and Roger D. Launius Launching NASA "An Act to provide for research into the problems of flight within and outside the Earth's atmosphere, and for other purposes." With this simple preamble, the Congress and the President of the United States created the national Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on October 1, 1958. NASA's birth was directly related to the pressures of national defense. After World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Cold War, a broad contest over the ideologies and allegiances of the nonaligned nations. During this period, space exploration emerged as a major area of contest and became known as the space race. During the late 1940s, the Department of Defense pursued research and rocketry and upper atmospheric sciences as a means of assuring American leadership in technology. A major step forward came when President Dwight D. Eisenhower approved a plan to orbit a scientific satellite as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) for the period, July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958, a cooperative effort to gather scientific data about the Earth. The Soviet Union quickly followed suit, announcing plans to orbit its own satellite. The Naval Research Laboratory's Project Vanguard was chosen on 9 September 1955 to support the IGY effort, largely because it did not interfere with high-priority ballistic missile development programs. -

The Cassini-Huygens Mission Overview

SpaceOps 2006 Conference AIAA 2006-5502 The Cassini-Huygens Mission Overview N. Vandermey and B. G. Paczkowski Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 The Cassini-Huygens Program is an international science mission to the Saturnian system. Three space agencies and seventeen nations contributed to building the Cassini spacecraft and Huygens probe. The Cassini orbiter is managed and operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The Huygens probe was built and operated by the European Space Agency. The mission design for Cassini-Huygens calls for a four-year orbital survey of Saturn, its rings, magnetosphere, and satellites, and the descent into Titan’s atmosphere of the Huygens probe. The Cassini orbiter tour consists of 76 orbits around Saturn with 45 close Titan flybys and 8 targeted icy satellite flybys. The Cassini orbiter spacecraft carries twelve scientific instruments that are performing a wide range of observations on a multitude of designated targets. The Huygens probe carried six additional instruments that provided in-situ sampling of the atmosphere and surface of Titan. The multi-national nature of this mission poses significant challenges in the area of flight operations. This paper will provide an overview of the mission, spacecraft, organization and flight operations environment used for the Cassini-Huygens Mission. It will address the operational complexities of the spacecraft and the science instruments and the approach used by Cassini- Huygens to address these issues. I. The Mission Saturn has fascinated observers for over 300 years. The only planet whose rings were visible from Earth with primitive telescopes, it was not until the age of robotic spacecraft that questions about the Saturnian system’s composition could be answered.