Philosophy of Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Docuseries Flat Out, Produced by Vuguru the Non-fi Ction Camp

MAY / JUNE 13 THE REALITY REPORT Syfy’s Haunted Highway and adventures in the US $7.95$7.95 USD New Paranormal CanadaCanada $$8.958.95 CDN Int’lInt’l $$9.959.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: UNSCRIPTED GOES ONLINE | U.S. CABLE SLATES REVEALED GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRealscreenealscreen Cover.inddCover.indd 1 116/05/136/05/13 22:16:16 PPMM Congratulations Bertram We are proud to call you family. CBS is proud to support the Realscreen Awards. ©2013 CBS Corporation RRS.23322.CBS.inddS.23322.CBS.indd 1 113-05-163-05-16 22:01:01 PPMM contents may / june 13 Sundance Grand Jury and Audience Award winner 35 42 Blood Brother is part of our annual Festival Report. BIZ Unscripted action at the NewFronts; Dubuc and Raven upped at A+E ......................................................... 9 Super 8 fi lm shot by Nixon’s top aides is featured in Our Nixon (Still courtesy of Dipper Films). IDEAS & EXECUTION U.S. cable nets unveil slates; crowdfunding words of wisdom ...........13 “The perception was you SPECIAL REPORTS could pitch a show on a THE REALITY REPORT A look into the Emmy Reality Peer Group; log line, put 10 cameras paranormal reality revamps .............................................................. 27 somewhere, and that STOCK FOOTAGE/ARCHIVE was reality.” 29 Super 8 rules in Our Nixon; 1895 Films’ 9-11: The Heartland Tapes; FOCAL Awards winners and UK copyright news ...............................35 FESTIVAL REPORT 19 Profi les of Gideon’s Army and Blood Brother .......................................40 PRODUCTION MUSIC Music shop execs reveal the dollars and sense behind scoring for shows .................................................45 THINK ABOUT IT Science Channel’s slate features a move into scripted Making talent agreements agreeable ...............................................48 drama, with 73 Seconds: The Challenger Investigation. -

A History of Globalization 1750-2050

Department of History University of Warwick 3rd Year Advanced Option Course HI 31V A HISTORY OF GLOBALIZATION 1750-2050 Module Booklet 2018-19 Course Tutor: Giorgio Riello Department of History Room H014, ext. 22163 Email: [email protected] 1 HI 31V ONE WORLD: A HISTORY OF GLOBALIZATION, 1750-2050 Context We are perennially told that we live in a ‘global society’, that the world is fast becoming a ‘global village’ and that this is an age of ‘globalisation’. Yet globalisation, the increasing connectedness of the world, is not a new phenomenon. This course provides a historical understanding of globalisation over the period from the mid eighteenth century to the present. It aims to introduce students to key theoretical debates and multidisciplinary discussions about globalisation and to reflect on what a historical approach might add to our understanding of our present-day society and economy. The course considers a variety of topics including the environment, migration, the power of multinationals and financial institutions, trade, communication and the critique of globalisation. Principal Aims To introduce students through a thematic approach to modern global history (post 1750) and the history of globalization. To introduce students to key theories of globalization. To train students to consider contemporary debates in a historical perspective. To explore a range of topics related to globalization and understand how some key features of human history have changed over the period from 1750 to the present. To understand how globalization has shaped people’s lives since the industrial revolution. To provide students with perspectives on Globalization from the point of view of different world areas (ex: China, India, and Africa). -

Globalization: a Short History

CHAPTER 5 GLOBALIZATIONS )URGEN OSTERHAMMEL TI-IE revival of world history towards the end of the twentieth century was intimately connected with the rise of a new master concept in the social sciences: 'globalization.' Historians and social scientists responded to the same generational experience·---·the impression, shared by intellectuals and many other people round the world, that the interconnectedness of social life on the planet had arrived at a new level of intensity. The world seemed to be a 'smaller' place in the 1990s than it had been a quarter century before. The conclusions drawn from this insight in the various academic disciplines, however, diverged considerably. The early theorists of globalization in sociology, political science, and economics disdained a historical perspective. The new concept seemed ideally suited to grasp the characteristic features of contemporary society. It helped to pinpoint the very essence of present-day modernity. Historians, on their part, were less reluctant to envisage a new kind of conceptual partnership. An earlier meeting of world history and sociology had taken place under the auspices of 'world-system theory.' Since that theory came along with a good deal of formalisms and strong assumptions, few historians went so far as to embrace it wholeheartedly. The idiom of 'globalization,' by contrast, made fewer specific demands, left more room for individuality and innovation and seemed to avoid the dogmatic pitfalls that surrounded world-system theory. 'Globalization' looked like a godsend for world historians. It opened up a way towards the social science mainstream, provided elements of a fresh terminology to a field that had sutlcred for a long time from an excess of descriptive simplicity, and even spawned the emergence of a special and up""ttHlate variant of world history-'global history.' Yet this story sounds too good to be true. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY BOOKS/BOOK CHAPTERS Ali, Saleem H. Treasures of the Earth: Need, Greed, and a Sustainable Future. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. Akiwumi, Fenda A. “Conflict Timber, Conflict Diamonds Parallels in the Political Ecology of the 19th and 20th Century Resource Exploration in Sierra Leone.” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agymang, and Kwamina Panford eds. Africa’s Development in the Twenty-First Century: Pertinent Socio-economic and Development Issues. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Anyinam, Charles. “Structural Adjustment Programs and the Mortgaging of Africa’s Ecosystems: The Case of Mineral Development in Ghana.” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agyemang ed. IMF and World Bank Sponsored Structural Adjustment Programs in African: Ghana’s Experience, 1983–1999. Burlington, USA: Ashgate, 2001. Appiah-Opoku, Seth. “Indigienous Knowledge and Enviromental Management in Africa: Evidence from Ghana” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agymang, and Kwamina Panford eds. Africa’s Development in the Twenty-First Century: Pertinent Socio- economic and Development Issues. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Ashun, Ato. Elmina, the Castle and the Slave Trade. Elmina, Ghana: Ato Ashun, 2004. Auty, Richard M. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis. New York: Routledge, 1993. Ayensu, Edward S. Ashanti Gold: The African Legacy of the World’s Most Precious Metal. Accra, Ghana: Ashanti Goldfields, 1997. © The Author(s) 2017 205 K. Panford, Africa’s Natural Resources and Underdevelopment, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54072-0 206 Bibliography Barkan, Joel D. Legislative Power in Emerging African Democracies. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2009. Boahen, A. Adu. Topics in West African History. London: Longman Group, 1966. Callaghy, Thomas M. “Africa and the World Political Economy: Still Caught Between a Rock and a Hard Place.” In John W. -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

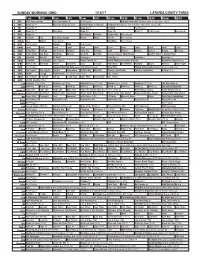

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

AN UPHILL BATTLE Campaigning for the Militarization of Belgium, 1870-1914

AN UPHILL BATTLE Campaigning for the Militarization of Belgium, 1870-1914 - Nel de Mûelenaere - Belgium plays a minor role, if it is mentioned at all, in the annals of the previously unparalleled European militarization that led to the First World War. This article presents a more nuanced image of Belgium as a non-militarized state during these decades, by focusing on the attempts of the militaristic political lobby to expand Belgium’s military infrastructure. Between 1870 and 1914, Belgium was indeed the scene of an intense militaristic movement that, despite its high level of activism, quickly fell into oblivion. At the start of their campaigns, in which the main goal was the adoption of personal military service, the militaristic lobbyists were primarily military or ex-military functionaries. The main motivation for their campaign was improving the sense of military purpose that acted as a preparation for war. This changed fundamentally throughout the campaigns. The militarists steadily built up a civilian network and expanded their influence. This was a key factor in the successful dissemination of the idea that a reformed Belgian army was very much needed in order to avert external dangers. At the same time, civilian influence altered the militarists’ view of the societal role of the military. This reciprocal influence reduced the gap between the military and civilian worlds, and suggests the presence of under- acknowledged militarization processes in Belgium prior to World War One. 145 Campaigning for the Militarization of Belgium I. Introduction ment of army officials and prominent Liberals pursuing the goal of a more powerful Belgian army. -

Globalization in Historical Perspective - David Northrup

WORLD SYSTEM HISTORY – Globalization in Historical Perspective - David Northrup GLOBALIZATION IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE David Northrup Department of History, Boston College, USA Keywords: Age of Divergence, globalization, Great Convergence, Great Divergence Contents 1. What is Globalization? 2. When did Globalization Begin? 2.1. The Industrial Revolution 2.2. The rise of the West 2.3. The Riches of the East 3. Turning Points 3.1. The Great Divergence of East and West 3.2 The Rise of the East 4. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary It is generally recognized that a phenomenon known as “globalization” is rapidly altering lives in every corner of the planet. However, here is little scholarly agreement about how to define globalization and when it began. This essay argues that it is necessary to define globalization broadly, including the interactions of political, cultural, social, and biological aspects, as well as the more obvious economic ones, in order to trace its historical development. After reviewing various starting points that researchers in different disciplines have proposed, the essay distinguishes remote “beginnings” from critical “tipping points” and identifies three major tipping points that led to the present process of global convergence: the consolidation of Asian and Indian Ocean networks beginning about a millennium ago, the new sea routes opened by European expansion about five centuries ago, and the Industrial Revolution of two centuries ago. It suggests that the past millennium during which societies came closer togetherUNESCO may be distinguished from the –rest ofEOLSS human history which was dominated by divergent forces that divided human communities from each other. 1. -

1 Introduction: Concepts of Globalization There Have Been

Introduction to Luke Martell, The Sociology of Globalization, 2010, pre-publication version. Introduction: Concepts of Globalization There have been many trends in sociology in recent decades. These have varied from country to country. One was a concern with class and social mobility from the 1950s onwards, in part evident in debates between Marxists and Weberians. In the ‘60s and ‘70s feminists argued that such debates had marginalised another form of social division, gender inequalities. Feminism grew in influence, itself being criticised for failing to appreciate other divisions, for instance ethnic inequalities identified by those with postcolonial perspectives. In the 1980s this concern with differences was highlighted in postmodern ideas, and the power of knowledge was analysed by theorists like Michel Foucault. In the 1980s and ‘90s a more homogenising idea came to the fore, globalization. This also then went on to stress local difference and plurality. The themes of globalization were not new, but the word and the popularity of the idea really came to the fore in the 1980s (an early mention is in Modelski 1972). Why did globalization become a popular idea? One reason is the rise of global communications, especially the internet, which made people feel that connections across the world were flowing more strongly, speedily and becoming more democratic. With the end of the cold war it seemed that the bipolar world had become more unified, whether through cultural homogenisation or the spread of capitalism. People became more conscious of global problems, like climate change. Economic interdependency and instability were more visible. Money flowed more freely and national economies went into recession together in the 1970s and again 30 years later. -

Urbanization in Brazil. an International Urbanization Survey Report to The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED P79 451 UD 013 732 AUTHOR Gardner, James A. TITLE Urbanization in .razil. An International Urbanization Survey Report to the Ford Foundation. INSTITUTION Ford Foundation, New York, N.Y. International Urbanization Survey. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 221p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS City Improvement; City Planning; Demography; *Developing Nations; Industrialization; Living Standards; National Programs; Population Distribution; Population Growth; *Urban Areas; Urban Immigration; *Urbanization; *Urban Population; Urban Renewal IDENTIFIERS *Brazil ABSTRACT . This report is a continuation of a review done in 1958 by the Ford Foundation in an attempt to identify and define a productive role in Latin America..Contained herein are as follows: The Introeuction includes: (1) Urbanization in Latin America, The Role of the Ford Foundation;(2) Urbanization in Brazil, the Involvement of the Ford Foundation;(3) The Need for a Frame of Reference in Approaching Urban Problems;(4) Whether 'Urban Problems' Constitute a Cognizable, Effective Category for Foundation Activity; (5) a Definition of Urbanization; (6) The Elements of an 'Urban Frame of Reference; and (7) The 'Frame of Reference' Origin of the Present Paper. The second section, Urbanization in Brazil, deals with: (1) The Absence of an Urban Tradition;(2) Physical Setting; (3) The Settlement and ',Urban'. History of Brazil..The third section, Brazilian Responses to Urbanization, includes: (1) 'Societal' Perception of Cities;(2) Governmental Responses to Urbanization; (3) Other Institutional Responses to Urbanization; and (4)'Urban Policy' in Brazil. Tables and charts are included throughout the text. [For related dk.cuments in this series, see UD 013 731 and 013 733-744 for surveys of specific countries. -

Globalization and Its Impacts on the World Economic Development

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 23 [Special Issue – December 2011] Globalization and its Impacts on the World Economic Development Muhammad Akram Ch. (1), Muhammad Asim Faheem (2) , Muhammad Khyzer Bin Dost (2), (3) Iqra Abdullah (1)Additional secretary higher Education Department, Punjab, Lahore (2)Lecturer, Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan (3)MS Scholar Department of Management Science COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Lahore Abstract The question whether the Globalization is beneficial for the World or harmful, is still unsolved and very controversial. Besides all of its disadvantages, it is an accepted reality that globalization is expanding very rapidly throughout the world. This paper is an attempt to find out what is the true sense of Globalization? How it is affecting the International Trade, FDI, and Economic Developments of overall word? This paper is mainly focusing on measuring how the Globalization is affecting the fastest growing industries of World. Key Words: Globalization, Economic Development of World, Fastest Growing Industries of World. Introduction Have you ever noticed that how close the different nations of the world are, in this era? If you visit a Super Store of Dubai, you will find all the commodities, imported from other countries. Only some commodities are there that are actually manufactured in United Arab Emirates. You will find the Electronic items made in Malaysia. Mobile phones made in India. Food items as fruits, rice etc are imported from Pakistan. This situation is not only limited to UAE, but the whole world is facing the same scenario. -

Chapter 2 Globalization: Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 Analyzed The

Chapter 2 Globalization: Past, Present and Future Chapter 1 analyzed the structure of the global economy that has been revealed by the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis from the viewpoints of the movement of people, goods, funds, and ideas (technological know-how and data) while taking into consideration the restrictions imposed on face-to-face communication due to the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 transmission through human-to-human interactions has largely spread due to the progress of globalization. However, until now, the world has achieved development thanks to globalization and the movement of people, goods and ideas (technological know-how and data). This chapter explains the conceptual framework of “unbundling” that was proposed by Baldwin (2016) to change the way of thinking about globalization, and discusses the past, present and future of globalization. In addition, the role of government, which has been changing amid globalization, is under the spotlight once again, raising expectations that government will play a role adapted to the ongoing globalization. Moreover, in the situation where the changing globalization and a network of economic partnership agreements (EPAs) showed combined effects, Japan has been transforming itself from a trading nation to an investment-oriented nation in recent years due to the development of supply chain networks, mainly in Asia, and an increase in outward foreign direct investment. On the other hand, the importance of dealing with the challenge of global sustainability has become clear. Looking toward the future of globalization, it is expected that the coming era will require more investments in digitalization and human resources. -

Coos County Veterans Search for CB Woman

C M C M Y K Y K HEAD OF CIA RESIGNS TOP DOGS Extramarital affair brings down Petraeus, A5 North Bend beats Klamath Union, B1 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2012 theworldlink.com I $1.50 Teams Honoring Coos County veterans search for CB woman BY TYLER RICHARDSON The World COOS BAY — Search teams from across Coos County are con- tinuing to look for a Coos Bay woman who has been missing since Tuesday. Members of the Coos County Sheriff’s Office, Coos Bay Police Department and Coos County Search and Res- cue searched the shoreline and wooded areas near the Empire By Alysha Beck, The World boat ramp for 59- World War II veteran Ross Turkle stands in front of the forty-and-eight boxcar outside the Coos Historical and Maritime Museum in North Bend. France gave the World War Il year-old Glenda boxcar to the U.S. as a sign of gratitude for help in the war.The boxcar is the same kind that Turkle and 38 other men rode in on the way back from East Germany. Glenda H. Campbell. Campbell CBPD Detec- Missing tive Randy Sparks said search teams are not sure if the woman is dead or alive. Living history “Your guess is as good as mine,” he said. Sparks said there is nothing to indicate any foul play is involved in Historic NORTH BEND — Ross Turkle turned 88 and is quick to point out that he served his Campbell’s disappearance, and this week, but a train ride he took through east time back from the front, with the heavy guns.