Urbanization in Brazil. an International Urbanization Survey Report to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oscar Niemeyer's Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings

Challenging the Hierarchies of the City: Oscar Niemeyer’s Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings Challenging the Hierarchies of the City: Oscar Niemeyer’s Mid-Twentieth-Century Residential Buildings Styliane Philippou [email protected] +44 20 7619 0045 Keywords: Oscar Niemeyer; architecture; Modernism; Brazilian city; mestiçagem; social, racial and gender city hierarchies Abstract This paper discusses the ways in which Oscar Niemeyer’s mid-twentieth-century residential buildings for the rapidly growing Brazilian cities challenged prevailing assumptions about the hierarchies of the city, and the profoundly patriarchal, white-dominated Brazilian society. The aesthetics of randomness and utilitarian simplicity of Niemeyer’s first house for himself (Rio de Janeiro, 1942) steered clear of any romanticisation of poverty and social marginalisation, but posited the peripheral, urban popular Black architecture of the morros as a legitimate source of inspiration for modern Brazilian residential architecture. At a time of explosive urban growth in Latin American cities, suburban developments allured those who could afford it to flee the city and retreat in suburbia. Niemeyer’s high density residential environment (Copan Apartment Building, 1951, São Paulo), right in the centre Brazil’s industrial metropolis, configured a site of resistance to urban flight and the ‘bourgeois utopia’ of the North American suburban, picturesque enclaves insulated from the workplace. The Copan’s irrational, feminine curves contrasted sharply with the ‘cold, hard, unornamental, technical image’ (Ockman) of the contemporaneous New York City Lever House, typical of the North American corporate capitalist landscape. At a time when Taylorism- influenced zoning was promoted as the solution to all urban problems, the Copan emphatically positioned in the city centre the peripheral realm of domestic, tropical, feminine curves, challenging prevailing images of the virile city of male business and phallic, stifling skyscrapers. -

Docuseries Flat Out, Produced by Vuguru the Non-fi Ction Camp

MAY / JUNE 13 THE REALITY REPORT Syfy’s Haunted Highway and adventures in the US $7.95$7.95 USD New Paranormal CanadaCanada $$8.958.95 CDN Int’lInt’l $$9.959.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: UNSCRIPTED GOES ONLINE | U.S. CABLE SLATES REVEALED GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. RRealscreenealscreen Cover.inddCover.indd 1 116/05/136/05/13 22:16:16 PPMM Congratulations Bertram We are proud to call you family. CBS is proud to support the Realscreen Awards. ©2013 CBS Corporation RRS.23322.CBS.inddS.23322.CBS.indd 1 113-05-163-05-16 22:01:01 PPMM contents may / june 13 Sundance Grand Jury and Audience Award winner 35 42 Blood Brother is part of our annual Festival Report. BIZ Unscripted action at the NewFronts; Dubuc and Raven upped at A+E ......................................................... 9 Super 8 fi lm shot by Nixon’s top aides is featured in Our Nixon (Still courtesy of Dipper Films). IDEAS & EXECUTION U.S. cable nets unveil slates; crowdfunding words of wisdom ...........13 “The perception was you SPECIAL REPORTS could pitch a show on a THE REALITY REPORT A look into the Emmy Reality Peer Group; log line, put 10 cameras paranormal reality revamps .............................................................. 27 somewhere, and that STOCK FOOTAGE/ARCHIVE was reality.” 29 Super 8 rules in Our Nixon; 1895 Films’ 9-11: The Heartland Tapes; FOCAL Awards winners and UK copyright news ...............................35 FESTIVAL REPORT 19 Profi les of Gideon’s Army and Blood Brother .......................................40 PRODUCTION MUSIC Music shop execs reveal the dollars and sense behind scoring for shows .................................................45 THINK ABOUT IT Science Channel’s slate features a move into scripted Making talent agreements agreeable ...............................................48 drama, with 73 Seconds: The Challenger Investigation. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY BOOKS/BOOK CHAPTERS Ali, Saleem H. Treasures of the Earth: Need, Greed, and a Sustainable Future. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. Akiwumi, Fenda A. “Conflict Timber, Conflict Diamonds Parallels in the Political Ecology of the 19th and 20th Century Resource Exploration in Sierra Leone.” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agymang, and Kwamina Panford eds. Africa’s Development in the Twenty-First Century: Pertinent Socio-economic and Development Issues. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Anyinam, Charles. “Structural Adjustment Programs and the Mortgaging of Africa’s Ecosystems: The Case of Mineral Development in Ghana.” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agyemang ed. IMF and World Bank Sponsored Structural Adjustment Programs in African: Ghana’s Experience, 1983–1999. Burlington, USA: Ashgate, 2001. Appiah-Opoku, Seth. “Indigienous Knowledge and Enviromental Management in Africa: Evidence from Ghana” In Kwadwo Konadu-Agymang, and Kwamina Panford eds. Africa’s Development in the Twenty-First Century: Pertinent Socio- economic and Development Issues. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Ashun, Ato. Elmina, the Castle and the Slave Trade. Elmina, Ghana: Ato Ashun, 2004. Auty, Richard M. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis. New York: Routledge, 1993. Ayensu, Edward S. Ashanti Gold: The African Legacy of the World’s Most Precious Metal. Accra, Ghana: Ashanti Goldfields, 1997. © The Author(s) 2017 205 K. Panford, Africa’s Natural Resources and Underdevelopment, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54072-0 206 Bibliography Barkan, Joel D. Legislative Power in Emerging African Democracies. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2009. Boahen, A. Adu. Topics in West African History. London: Longman Group, 1966. Callaghy, Thomas M. “Africa and the World Political Economy: Still Caught Between a Rock and a Hard Place.” In John W. -

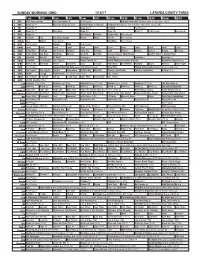

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

THE U.S. STATE, the PRIVATE SECTOR and MODERN ART in SOUTH AMERICA 1940-1943 By

THE U.S. STATE, THE PRIVATE SECTOR AND MODERN ART IN SOUTH AMERICA 1940-1943 by Olga Ulloa-Herrera A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA The U.S. State, the Private Sector and Modern Art in South America 1940-1943 A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Olga Ulloa-Herrera Master of Arts Louisiana State University, 1989 Director: Michele Greet, Associate Professor Cultural Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2014 Olga Ulloa-Herrera All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to Carlos Herrera, Carlos A. Herrera, Roberto J. Herrera, and Max Herrera with love and thanks for making life such an exhilarating adventure; and to María de los Angeles Torres with gratitude and appreciation. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair Dr. Michele Greet and to my committee members Dr. Paul Smith and Dr. Ellen Wiley Todd whose help, support, and encouragement made this project possible. I have greatly benefited from their guidance as a student and as a researcher. I also would like to acknowledge Dr. Roger Lancaster, director of the Cultural Studies Program at George Mason University and Michelle Carr for their assistance throughout the years. -

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Secretaría De Unidad Coordinación De Servicios De Información

Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Secretaría de Unidad Coordinación de Servicios de Información Sección de Hemeroteca En la de Sección Hemeroteca contamos con un acervo hemerográfico de 820 títulos de revistas impresas especializadas, de las cuales 162 apoyan la Licenciatura en Arquitectura de la División de Ciencias y Artes para el Diseño. La UAM ha suscrito alrededor de 10,000 revistas en formato electrónico disponibles en texto completo que abarcan todas las áreas del conocimiento para apoyar las funciones académicas de la Comunidad Universitaria, y de las cuales 1,025 apoyan a División de Ciencias y Artes para el Diseño. Las revistas electrónicas las puede consultar en la siguiente dirección electrónica: http://www.bidi.uam.mx/ La Comunidad Universitaria puede consultar las revistas electrónicas a través del portal de la biblioteca digital ya sea dentro de la red UAM o de forma remota con su número económico o matrícula y el NIP de servicios bibliotecarios. Publicaciones Periódicas Impresas “Licenciatura en Arquitectura" TÍTULO DE LA REVISTA DIVISIÓN 1 A+U ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM CAD 2 ABITARE CAD 3 ACER CAD 4 ACSA NEWS CAD 5 ADMINISTRACIÓN Y TECNOLOGÍA PARA EL DISEÑO CAD ADVERTISING JOURNAL & GRAPHIS ADVERTISING 6 ANNUAL CAD 7 AIA JOURNAL ARCHITECTURE CAD 8 AMIGA USER INTERNATIONAL CAD 9 ANNALES DE LA RECHERCHE URBANIE CAD 10 ANUARIO DE ESPACIOS URBANOS CAD 11 ANUARIO DE ESTUDIOS DE ARQUITECTURA CAD 12 ARCHITEC NORTHBOOK CAD 13 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CAD 14 ARCHITECTURAL DIGEST CAD 15 ARCHITECTURAL RECORD CAD 16 ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW CAD 17 ARCHITECTURE CAD 18 ARCHITECTURE D'AUJOURD HUI CAD 19 ARCHIVES DÁRCHITECTURE MODERNE CAD 20 ARCHIVIO DI STUDI URBANI E REGIONALI CAD 21 ARQ. -

Coos County Veterans Search for CB Woman

C M C M Y K Y K HEAD OF CIA RESIGNS TOP DOGS Extramarital affair brings down Petraeus, A5 North Bend beats Klamath Union, B1 Serving Oregon’s South Coast Since 1878 SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2012 theworldlink.com I $1.50 Teams Honoring Coos County veterans search for CB woman BY TYLER RICHARDSON The World COOS BAY — Search teams from across Coos County are con- tinuing to look for a Coos Bay woman who has been missing since Tuesday. Members of the Coos County Sheriff’s Office, Coos Bay Police Department and Coos County Search and Res- cue searched the shoreline and wooded areas near the Empire By Alysha Beck, The World boat ramp for 59- World War II veteran Ross Turkle stands in front of the forty-and-eight boxcar outside the Coos Historical and Maritime Museum in North Bend. France gave the World War Il year-old Glenda boxcar to the U.S. as a sign of gratitude for help in the war.The boxcar is the same kind that Turkle and 38 other men rode in on the way back from East Germany. Glenda H. Campbell. Campbell CBPD Detec- Missing tive Randy Sparks said search teams are not sure if the woman is dead or alive. Living history “Your guess is as good as mine,” he said. Sparks said there is nothing to indicate any foul play is involved in Historic NORTH BEND — Ross Turkle turned 88 and is quick to point out that he served his Campbell’s disappearance, and this week, but a train ride he took through east time back from the front, with the heavy guns. -

The Rise of Popular Modernist Architecture in Brazil'

H-LatAm Carranza on Lara, 'The Rise of Popular Modernist Architecture in Brazil' Review published on Monday, February 6, 2012 Fernando Luiz Lara. The Rise of Popular Modernist Architecture in Brazil. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008. xvi + 149 pp. $69.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8130-3289-4. Reviewed by Luis Carranza (School of Architecture, Roger Williams University)Published on H- LatAm (February, 2012) Commissioned by Dennis R. Hidalgo Architecture in the Hands of the People Ever since Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa built the Brazilian Pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, American architects have been fascinated by Brazilian modernism. While the historiography of modern architecture has, generally speaking, marginalized Latin American architectural production, it has acknowledged the formal innovations accomplished by Costa and Niemeyer in their attempt to adapt the modern architectural idiom--characteristic of the Bauhaus or architects like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe--to the specifics of the Brazilian context. Key exhibitions and their publications (including the Museum of Modern Art’sBrazil Builds [1943] and, more recently, the Guggenheim Museum’sBrazil: Body and Soul, [2001]) have addressed the paradigmatic work of these two architects and the unique modern, international style of architecture that they produced. Despite this, little or no attention has been paid in the United States to the other Brazilian architects and their contributions. This, however, is changing. Recently more works that address the general lack of information on and interpretation of Latin American architecture are beginning to appear and thus are expanding the limited scholarship available on other Brazilian architects. -

October 30, 2013 • Vol

The WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2013 • VOL. 24, NO.13 $1.25 Have a Spooktacular Hallowe'en everyone! KLONDIKEThe Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Singers SUN Still not much ice, but the Ferry is done The Jerry Cans Relatively small amounts of ice appeared in front of Dawson last week, but not enough to bother the George Black, and after two days of increasing pans, there seemed to be less on Friday than on Wednesday and Thursday. By Saturday the Highways Dept. had made its decision, shown here, which was amended to read "NOON" by Monday morning. It's later than last year though, and it sure beats the six-hour panic of 2012. Photo by Dan Davidson in this Issue Maximilian's has all kinds of Hospital update 3 What is REM? 10 & 19 A report from Columbia 13 Hospital siding goes on, again. The Rural Experiential Model Anna Vogt reports from Bogota. candles to keep you home Comes to RSS. cozy and bright this winter. What to see and do in Dawson! 2 More info on the Hospital 5 SOVA students hybredize 11 Authors on Eighth entries 20 & 21 Council Tribute to Dick North 3 Legion news 6 TV Guide 14-18 Business Directory & Job Board 23 Uffish Thoughts 4 Tourism roundup report 7 Murphy on Berton House 19 City Notices 24 Happy 26th Birthday Andrea Parent! P2 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2013 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: SOVA ADMIN OFFICE HOUrs This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. -

GSN Edition 08-06-20

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, August 6, 2013 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 81, Number 63 10 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 weather Large sink hole opens in Wallace County Leadership report Kansas 83° 10 a.m. Monday stops in Today • Sunset, 7:53 p.m. Wednesday Goodand • Sunrise, 5:53 a.m. By Kevin Bottrell • Sunset, 7:52 p.m. [email protected] Midday Conditions Forty students from Leadership • Soil temperature 74 degrees Kansas spent the better part of three • Humidity 60 percent days in Goodland and Colby last • Sky sunny month, learning about economic, • Winds south 6 mph agricultural and educational issues • Barometer 30.02 inches in western Kansas. and falling This year’s class includes Doug • Record High today 108° (1970) Gerber and Joseph Bain from Good- • Record Low today 42° (1974) land. Each year about 500 people are nominated, while only 40 are Last 24 Hours* selected during the application High Sunday 88° process. The students travel all over Low Sunday 65° Kansas, learning about the different Precipitation none economic and social issues faced by This month trace Kansans. Year to date 7.83 Jenifer Sanderson, who served Below normal 5.78 inches This sinkhole – approximately 200 feet in diameter and 80 to pasture land, about a mile from the nearest house and one mile as local program chair and was in The Topside Forecast 90 feet deep – opened last week in rural Wallace County, about from a previous sinkhole that had opened in 1926. The land has Today: Mostly sunny with a 20 eight miles north of the city of Wallace. -

Global Baroque – Transcultural and Transhistorical Aspects: Some Prelimenary Reflections

Global Baroque – transcultural and transhistorical aspects: some prelimenary reflections Jens Baumgarten Professor at Art History Department – Federal University of São Paulo – UNIFESP ABSTRACT In the last years the term of a global baroque bacame more prominent. This article presented as prelimenary reflections intends to contextualize this transhistorical and transcultural approach within the developments of the so-called global art history. It also tries to (de-)construct its historiographical fundaments in the 19th century as well as its possible theoretical implications for the 21st century. KEYWORDS Baroque, Theory, Historiography. Fig. 1: Façade of San Joaquin Church, 1869, Iloilo, Philippines. Photo: Jens Baumgarten. RHAA 24 - JUL/DEZ 2015 29 Fig. 2: Façade of Miagao Church, 1787, Iloilo, Philippines. Photo: Jens Baumgarten. The façade of the church San Joaquin on the Filipino island of Iloilo shows on its upper part a monumental relief [Fig. 1]. It joins several scenes of the victory of the Spanish victory over the “Moors” in the battle of Tétouan, which happened in 1860 in Morrocos. The representation surprizes by its stylistic and iconographical choices. The history painting of the 19th century was already established, but the choice of the local authorities followd in a record time – the execution happened already in 1865 – followed the Baroque models of a specific Filipino model. This model can for example be found in the Miagao Church only 40 kilometers of distance [Fig. 2]. This example not only proves the expression of Kosselleck: “Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen” (Simultaneoutiy of the unsimultaneous), but show the possibilities of a transcultural and transhistorical baroque approach to understand these phenomens as well as these kind of artifacts, which were excluded from a traditional art history. -

P25 Layout 1

Established 1961 25 TV Thursday, May 10, 2018 13:05 Friends 17:40 Hotel Transylvania: The Series 22:25 Phineas And Ferb 09:25 Maximum Foodie 01:54 Kid-E-Cats 20:00 How To Get Away With 13:30 Friends 18:05 K.C. Undercover 23:00 Programmes Start At 6:00am 09:55 The Food Files 01:59 Kid-E-Cats Murder 13:55 Ridiculousness Arabia 18:30 Bunk’d 10:20 The Food Files 02:04 Shimmer And Shine 21:00 Supergirl 14:20 Workaholics 18:55 Descendants Wicked World 10:50 George Clarke’s Amazing 02:26 Nella The Princess Knight 22:00 Lethal Weapon 14:45 Disaster Date 19:00 Raven’s Home Spaces 02:38 Paw Patrol 23:00 S.W.A.T. 01:20 The Bodyguard 15:10 Friends 19:25 Liv And Maddie 11:45 Pond Stars 03:02 Max & Ruby 03:05 Captain America: Civil War 15:35 Lip Sync Battle 19:50 Jessie 12:40 Confucius Was A Foodie 03:23 Dora The Explorer 05:45 Seven Years In Tibet 16:00 Key And Peele 20:15 Disney Mickey Mouse 00:05 Botched 13:35 John Torode’s Korean Food 03:46 Sunny Day 08:15 Being Evel 16:30 Friendszone 20:20 Tangled: The Series 00:55 Botched Tour 04:09 Nella The Princess Knight 10:05 The Bodyguard 16:55 Friends 20:45 Bizaardvark 01:50 E! News 14:30 Maximum Foodie 04:31 Shimmer And Shine 11:45 Captain America: Civil War 17:20 Friends 21:10 Hotel Transylvania: The Series 02:50 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 14:55 Chocolate Covered 04:42 Shimmer And Shine 01:20 Sam 14:25 Starship Troopers: Traitor Of 17:45 Disaster Date 21:35 Stuck In The Middle 03:40 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 15:25 The Food Files 04:54 Wallykazam! 03:05 Boris And Natasha: The Mars 18:10 Takeshis Castle