Frauberger Ritual Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ( Biblica Tr PRESENTED BY ALFRED C. BARNES. NOT TO BE TAKEN IL, FROM THE ROOM. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 070 685 833 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924070685833 — — — — — — T. and T. Clark's Publications. In Three Volumes, Imperial 8vo, price 24.S. each, ENCYCLOPEDIA OR DICTIONARY OF BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, DOCTRINAL, AND PRACTICAL THEOLOGY. BASED ON THE REAL-ENCYKLOPADIE OF HERZ06, PLITT, AND H4DCK. EDITED BY PHILIP SCHAFF, D.D., LL.D., PROFESSOR IN THE UNION THEOLOaiCAL SEMINARY, NEW TORK. 'As a compreliensiTe work of reference, within a moderate compass, we know nothing at all equal to it in the large department which it deals with.' Church Bells. ' The work will remain as a wonderful monument of industry, learning, and skill. It will be indispensable to the student of specifically Protestant theology ; nor, indeed do we think that any scholar, whatever be his especial line of thought or study, would find it superfluous on his shelves.' Literary Churchman, 'We commend this work with a touch of enthusiasm, for we have often wanted such ourselves. It embraces in its range of writers all the leading authors of Europe on ecclesiastical questions. A student may deny himself many other volumes to secure this, for it is certain to take a prominent and permanent place in our literature.' jEvangelical Magazine. 'Dr. Schaff's name is a guarantee for valuable and thorough work. His new Eacyclo- pasdia (based on Herzog) will be one of the most useful works of the day. -

Raphael Meldola in Livorno, Pisa, and Bayonne

Chapter 7 Defining Deviance, Negotiating Norms: Raphael Meldola in Livorno, Pisa, and Bayonne Bernard Dov Cooperman* 1 The Secularization Thesis The link between modernization and secularization has long been a staple of Jewish historiography. Secularization was the necessary prerequisite for, and the inevitable response to, Jews’ “emancipation” from discriminatory legal provisions. It was evidenced in the abandonment of Jewish ritual observance, an intentional imitation of external norms that was either to be praised as “enlightenment” or decried as “assimilation,” and the abandonment of Jewish “authenticity.” The decline in observance was accompanied by, or justified by, a parallel abandonment of traditional religious beliefs and theological concepts. And at the same time, the kehilla, the autonomous Jewish community, lost its ability to enforce religious discipline and suppress unacceptable religious ideas.1 Thus the transition to modernity was equated with a decline in rabbini- cal and communal authority, the abandonment of traditional behaviors, and the collapse of orthodox mentalities. In a famous article published almost a century ago, the young historian Salo Baron questioned whether moderniza- tion had been worth such a great cultural and communal cost.2 But he did not question the narrative itself; if anything, his regret over what was lost rein- forced the assumption that modernization and secularization were one. * My thanks to Professors Gérard Nahon and Peter Nahon as well as to Doctor Nimrod Gaatone for their thoughtful comments on this paper. While I was unable to take up their several ex- cellent suggestions here, I hope to do so in further work on Meldola. Of course, all errors are my own. -

Story Parsha

a project of www.Chabad.org Chanukah 5763 (2002) The Lightness of Being Comment If you recorded every word you said for 24 hours, you'd probably find hundreds of refer- ences to light. Light, brightness, radiance -- these A little bit of light dispels a lot are the metaphors we use when we wish to speak about hope, wisdom, and goodness of darkness. Shutters and Blinds Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi Voices What does light give? The details. The color and texture. The fullness and the goodness. It balances the shadows and fills in the outlines, so that the remaining darkness only adds contrast, complexity, beauty and interest to my world Why Couldn't the Jews and Greeks Question Just Get Along? The Jews and Greeks could have learned so much from each other! Instead, the extremists of both sides hit the battlefield without actually The Path of Light being there When He made the world, He made two ways to repair each Eight Chanukah Stories Story Judea, 139 BCE... Heaven, 25 Kislev, 3622 from thing: With harshness or with creation... Mezhibuzh, 18th Century... France, compassion. With a slap or with a 1942... Kharkov, 1995... Los Angeles, 2002... caress. With darkness or with light. And He looked at the light and Seasons of the Eight Shades of Light saw that it was good. Darkness In the beginning, darkness and light were one. and harsh words may be neces- Soul Then G-d separated between revealed good and sary. But He never called them concealed good, challenging us to cultivate the good. -

Gender in Jewish Studies

Gender in Jewish Studies Proceedings of the Sherman Conversations 2017 Volume 13 (2019) GUEST EDITOR Katja Stuerzenhofecker & Renate Smithuis ASSISTANT EDITOR Lawrence Rabone A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by © University of Manchester, UK. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, the University of Manchester, and the co-publisher, Gorgias Press LLC. All inquiries should be addressed to the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester (email: [email protected]). Co-Published by Gorgias Press LLC 954 River Road Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA Internet: www.gorgiaspress.com Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4632-4056-1 ISSN 1759-1953 This volume is printed on acid-free paper that meets the American National Standard for Permanence of paper for Printed Library Materials. Printed in the United States of America Melilah: Manchester Journal of Jewish Studies is distributed electronically free of charge at www.melilahjournal.org Melilah is an interdisciplinary Open Access journal available in both electronic and book form concerned with Jewish law, history, literature, religion, culture and thought in the ancient, medieval and modern eras. Melilah: A Volume of Studies was founded by Edward Robertson and Meir Wallenstein, and published (in Hebrew) by Manchester University Press from 1944 to 1955. Five substantial volumes were produced before the series was discontinued; these are now available online. -

Accents, Punctuation Or Cantillation Marks?

Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? A Study of the Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger Masteroppgave i SEM4090 Semittisk Språkvitenskap 60 studiepoeng Program: Asiatiske og afrikanske studier Studieretning: Semittisk språkvitenskap med hebraisk Instituttet for kulturstudier og orientalske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 1. juni 2012 II Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? A Study of the Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger (Proverbs 1:7) יִרְאַ ַ֣תיְְ֭הוָ ה רֵ אשִ ַ֣ ית דָ ָּ֑עַ ת III © Matthew Phillip Monger 2012 Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? The Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This thesis discusses different strategies for interpreting the placement of the ṭəʿ in Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible. After introducing the signs and their distribution in the text, the thesis looks at different levels of linguistic analysis where the ṭəʿ provide interesting information. At the word level, word stress and vowel length are discussed. At the phrase level, the different types of phrases are analyzed in light of a closest constituent analysis. At the verse level, the distribution of the ṭəʿ is shown to depend on simple rules which maximize the most common structures of Tiberian Hebrew. Prosodic structure is also evaluated to show what bearing that it has on the placement of the ṭəʿ . Finally, the ṭəʿ are discussed in relation to discourse features. The goal of the thesis is to show that the ṭəʿ are not simply musical notation, but have a linguistic basis, and provide insight into linguistic features of Tiberian Hebrew. -

A New View of Women and Torah Study in the Talmudic Period

JSIJ 9 (2010) 249-292 A NEW VIEW OF WOMEN AND TORAH STUDY IN THE TALMUDIC PERIOD JUDITH HAUPTMAN* Introduction1 Scholars have long maintained that women did not study Torah in the rabbinic period. D. Goodblatt claims that it was uncommon for a woman to be learned in rabbinic traditions.2 D. Boyarin writes that women’s voices were suppressed in the Houses of Study.3 T. Ilan and D. Goodblatt both hold that women learned domestic rules and biblical verses, but not other subjects.4 S.J.D. Cohen says that women * Jewish Theological Seminary, NY 1 I wish to thank Aharon Shemesh, Arnon Atzmon, and Shmuel Sandberg for their helpful comments and suggestions. 2 D. Goodblatt, in “The Beruriah Traditions,” (JJS 1975, 86) writes: “the existence of a woman learned in rabbinic traditions was a possibility, however uncommon.” 3 D. Boyarin, in Carnal Israel (Berkeley: University of California Press 1993, 169), writes: “My major contention is that there was a significant difference between the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds with regard to the empowering (or disempowering) of women to study Torah. Both in the Palestinian and in the Babylonian text the dominant discourse suppressed women’s voices in the House of Study. These texts, however, provide evidence that in Palestine a dissident voice was tolerated, while in Babylonia this issue seems to have been so threatening that even a minority voice had to be entirely expunged.” He adds that it is possible that the suppression of women’s voices in Babylonia could either mean that women did not have access to Torah study or, just the opposite, that they frequently studied Torah. -

The Open Torah Ark a Jewish Iconographic Type in Late Antique Rome and Sardis

chapter 6 The Open Torah Ark A Jewish Iconographic Type in Late Antique Rome and Sardis Steven Fine* Scholars have long noted that images of Torah Shrines are markedly different in the Land of Israel from those that appear in Jewish contexts in and around Rome (see Hachlili 1988, 166–87, 247–49, 270–80; 1998, 67–77, 363–73; 2000; 2013, 192–205 and references there). In Palestinian exempla—in mortuary contexts, reliefs, occasionally on a ritual object and especially on mosaic syna- gogue pavements—the doors of the cabinet are almost always closed. This is the case within both Jewish and Samaritan contexts (Meyers 1999; Magen 2008, 134–37; Hachlili 2013, 192–203; Figs. 6.1–6.3). Only one image of an ark contain- ing scrolls has been discovered in Israel, a rather primitive graffito found in the Jewish catacombs at Beth Sheʿarim (Hachlili 1988, 247), a burial compound known for having served Jews from both Palestine and the nearby Diaspora communities (Rajak 2001). By contrast, in Rome (Figs. 6.4–6.6), and in the Sardis synagogue in Lydia in Asia Minor (Fig. 6.7), the Torah Shrine is presented open, with scrolls exposed (Hachlili 1998, 362–67). Happily, Rachel Hachlili has handily collected and made available all of the extant evidence of Torah Shrines from both Israel and the Diaspora. Her corpora (1988; 1998) are now a touchstone for the study of this material, allowing all who have followed after her the luxury of a fully orga- nized body of sources, and readily available. This alone is a major accomplish- ment, one that I am pleased to celebrate with this chapter. -

Ritual Objects1 by Karl Schwarz Virtually Nothing Is Known of Ritual

Ritual objects1 By Karl Schwarz Virtually nothing is known of ritual objects from early times. The various items which were produced with great care seem—at least in part—to have been made by Christians, as Jews were forbidden from working as artisans to a large extent. Gold and silversmiths existed in virtually all countries. They had their own places in the large synagogue in Alexandria. In the 6th century in North Arabia, the Jewish tribe Qaynuqa worked as goldsmiths and in 1042 Archbishop Guifred sold the Narbonne church treasure to Jewish goldsmiths from the Languedoc. They must have carried out this craft in Spain and Portugal as well, as they are to be found in Hamburg among those expelled and in Mexico among the Marranos. Different mentions of the name Zoref, “goldsmith,” can be found in inscriptions in Prague cemetery. It is to be assumed that this word, which soon became a family name, resulted from the prevalence of the craft. However, no works created by these craftsmen have survived. As a result, the extent to which their work was based on artistic qualities cannot be ascertained. Just how widespread the goldsmith’s craft was among Jews in Poland can be seen in a plea handed to King Sigismund I (1505–1548): “Ad Querelam mercatorum Cracoviensium responsum Judaeorum de mercatura,” in which statistic evidence reveals that, after clothmakers and furriers, goldsmiths were in third place. In 1857, the “statistic calendar” of the Kingdom of Poland cited the number of Jewish goldsmiths in the kingdom, excluding Warsaw, as 533. Many worked predominantly on making ritual objects and advanced to become true masters of their craft. -

Jewish Book and Arts Festival

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 The Jewish Musical Permit No. 85 Urban Volunteers Theater Kibbutz and with Movement VNP Ari Axelrod page 16 page 19 page 21 October 2018 Tishrei/Cheshvan 5778 Volume XVIII Number 2 FREE Old world meets new world for the Arts Around Town: Jewish Book and Arts Festival Clara Silver, special to the WJN he Jewish Community Center of Friends of Magen David Adom at afmda.org/ On Thursday, Kahn’s unique contribution to the creation Greater Ann Arbor will present Arts event/talk-with-alan-dershowitz. October 25, the eve- of modern manufacturing as well as his role T Around Town: Jewish Book and Arts The annual Book and Gift Sale concur- ning will begin with in defending and preserving the famous Di- Festival beginning Thursday, October 18, rent with Arts Around Town will open the the annual sponsor ego Rivera mural at the Detroit Institute of and continuing through Monday, November same evening, Thursday, October 18, in the dinner at 6 p.m., for Art, and his role in helping the Soviets push 12. For 31 years the JCC has produced a fes- atrium of the JCC. A variety of books of those members of the back the Nazis in 1941–1942. tival — originally exclusively a book festival popular genres, as well as books from the Arts Around Town will host photographer — which has evolved to a broader festival presenters and authors who will be guest of Leslie Sobel on Sunday, October 29, for a recep- celebrating authors and artists of all kinds. -

Day One of the Omer Devotional

1 A STUDY ON THE RUACH HAKODESH AND HIS SPIRITUAL GIFTS Study One Isaiah 61:1-3 Isa 61:1 The Spirit of the Lord GOD (YHWH ELOHIM) is upon me, Because the LORD has anointed me To bring good news to the afflicted; He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, To proclaim liberty to captives And freedom to prisoners; Isa 61:2 To proclaim the favorable year of the LORD And the day of vengeance of our God; To comfort all who mourn, Isa 61:3 To grant those who mourn in Zion, Giving them a garland instead of ashes, The oil of gladness instead of mourning, The mantle of praise instead of a spirit of fainting. So they will be called oaks of righteousness, The planting of the LORD, that He may be glorified. Words To Ponder Ruach Strongs #7307 – H7307 רּוח rûach roo'-akh From H7306; wind; by resemblance breath, that is, a sensible (or even violent) exhalation; figuratively life, anger, unsubstantiality; by extension a region of the sky; by resemblance spirit, but only of a rational being (including its expression and functions): - air, anger, blast, breath, X cool, courage, mind, X quarter, X side, spirit ([-ual]), tempest, X vain, ([whirl-]) wind (-y). Anointed H4886 מׁשח mâshach maw-shakh' A primitive root; to rub with oil, that is, to anoint; by implication to consecrate; also to paint: - anoint, paint. shemen sheh'-men ׁשמן Oil - H8081 From H8080; grease, especially liquid (as from the olive, often perfumed); figuratively richness: - anointing, X fat (things), X fruitful, oil ([-ed]), ointment, olive, + pine. -

OJL AUGUST WEB.Pdf

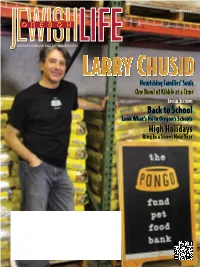

AUGUST 2013 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON Nourishing Families’ Souls One Bowl of Kibble at a Time SPECIAL SECTIONS BackBack toto SchoolSchool LookLook What’sWhat’s NuNu inin Oregon’sOregon’s SchoolsSchools HighHigh HolidaysHolidays RingRing inin aa SweetSweet NewNew YearYear A Place to Call our vision for the future HOME TRUSTWORTHY COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTIONS You’re Invited October 3rd, 2013 IDENTITY THEFT; How to protect yourself at home and overseas. visit our website or call to register for this complimentary event GRETCHEN STANGIER, CFP® WWW.STANGIERWEALTHMANAGEMENT.COM 9955 SE WASHINGTON, SUITE 101 • PORTLAND, OR 97216 • 877-257-0057 • [email protected] SECURITIES AND ADVISORY SERVICES OFFERED THROUGH LPL FINANCIAL. A REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISOR. MEMBER FINRA/SIPC. INVEST IN ISRAEL A Place to Call our vision for the future HOME 2013 · 5774 HIGH HOLIDAYS INVEST IN ISRAEL BONDS · ISRAELBONDS.COM Development Corporation for Israel/Israel Bonds This is not an offering, which can be made only by prospectus. Read the prospectus carefully Western Region before investing to fully evaluate the risks associated with investing in Israel bonds. Issues subject 4500 S. Lakeshore Drive, Suite 355 · AZ 85282 to availability. Member FINRA Photo Credits: pokku/Shutterstock.com; jvinasd/Shutterstock.com; 800.229.4324 · (fax) 480.948.7413 · [email protected] Nir Darom/Shutterstock.com; Noam Armonn/Shutterstock.com; Jim Galfund Table of Contents AUGUST 2013/ Av-Elul 5773 | Volume 2/Issue 7 [Cover Story] 28 Pongo Fund: Pet Food Bank Nourishes -

Handbook on Judaica Provenance Research: Ceremonial Objects

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America depositing Torah scrolls in a grave at Beth El Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 January 1952. Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBOOK ON JUDAICA PROVENANCE RESEARCH: CEREMONIAL OBJECTS By Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, and Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2018 Table of Contents Foreword, Wesley A. Fisher page 4 Disclaimer page 7 Preface page 8 PART 1 – Historical Overview 1.1 Pre-War Judaica and Jewish Museum Collections: An Overview page 12 1.2 Nazi Agencies Engaged in the Looting of Material Culture page 16 1.3 The Looting of Judaica: Museum Collections, Community Collections, page 28 and Private Collections - An Overview 1.4 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the West: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction page 43 1.5 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the East: The Soviet Trophy Brigades and Nationalizations in the East after World War II page 61 PART 2 – Judaica Objects 2.1 On the Definition of Judaica Objects page 77 2.2 Identification of Judaica Objects page 78 2.2.1 Inscriptions page 78 2.2.1.1 Names of Individuals page 78 2.2.1.2 Names of Communities and Towns page 79 2.2.1.3 Dates page 80 2.2.1.4 Crests page 80 2.2.2 Sizes page 81 2.2.3 Materials page 81 2.2.3.1 Textiles page 81 2.2.3.2 Metal page 82 2.2.3.3 Wood page 83 2.2.3.4 Paper page 83 2.2.3.5 Other page 83 2.2.4 Styles