Did the Synagogue Replace the Temple?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ( Biblica Tr PRESENTED BY ALFRED C. BARNES. NOT TO BE TAKEN IL, FROM THE ROOM. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 070 685 833 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924070685833 — — — — — — T. and T. Clark's Publications. In Three Volumes, Imperial 8vo, price 24.S. each, ENCYCLOPEDIA OR DICTIONARY OF BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, DOCTRINAL, AND PRACTICAL THEOLOGY. BASED ON THE REAL-ENCYKLOPADIE OF HERZ06, PLITT, AND H4DCK. EDITED BY PHILIP SCHAFF, D.D., LL.D., PROFESSOR IN THE UNION THEOLOaiCAL SEMINARY, NEW TORK. 'As a compreliensiTe work of reference, within a moderate compass, we know nothing at all equal to it in the large department which it deals with.' Church Bells. ' The work will remain as a wonderful monument of industry, learning, and skill. It will be indispensable to the student of specifically Protestant theology ; nor, indeed do we think that any scholar, whatever be his especial line of thought or study, would find it superfluous on his shelves.' Literary Churchman, 'We commend this work with a touch of enthusiasm, for we have often wanted such ourselves. It embraces in its range of writers all the leading authors of Europe on ecclesiastical questions. A student may deny himself many other volumes to secure this, for it is certain to take a prominent and permanent place in our literature.' jEvangelical Magazine. 'Dr. Schaff's name is a guarantee for valuable and thorough work. His new Eacyclo- pasdia (based on Herzog) will be one of the most useful works of the day. -

Raphael Meldola in Livorno, Pisa, and Bayonne

Chapter 7 Defining Deviance, Negotiating Norms: Raphael Meldola in Livorno, Pisa, and Bayonne Bernard Dov Cooperman* 1 The Secularization Thesis The link between modernization and secularization has long been a staple of Jewish historiography. Secularization was the necessary prerequisite for, and the inevitable response to, Jews’ “emancipation” from discriminatory legal provisions. It was evidenced in the abandonment of Jewish ritual observance, an intentional imitation of external norms that was either to be praised as “enlightenment” or decried as “assimilation,” and the abandonment of Jewish “authenticity.” The decline in observance was accompanied by, or justified by, a parallel abandonment of traditional religious beliefs and theological concepts. And at the same time, the kehilla, the autonomous Jewish community, lost its ability to enforce religious discipline and suppress unacceptable religious ideas.1 Thus the transition to modernity was equated with a decline in rabbini- cal and communal authority, the abandonment of traditional behaviors, and the collapse of orthodox mentalities. In a famous article published almost a century ago, the young historian Salo Baron questioned whether moderniza- tion had been worth such a great cultural and communal cost.2 But he did not question the narrative itself; if anything, his regret over what was lost rein- forced the assumption that modernization and secularization were one. * My thanks to Professors Gérard Nahon and Peter Nahon as well as to Doctor Nimrod Gaatone for their thoughtful comments on this paper. While I was unable to take up their several ex- cellent suggestions here, I hope to do so in further work on Meldola. Of course, all errors are my own. -

Archaeology in the Holy Land IRON AGE I

AR 342/742: Archaeology in the Holy Land IRON AGE I: Manifest Identities READING: Elizabeth Bloch-Smith and Beth Alpert Nahkhai, "A Landscape Comes to Life: The Iron Age I, " Near Eastern Archaeology 62.2 (1999), pp. 62-92, 101-27; Elizabeth Bloch-Smith, "Israelite Ethnicity in Iron I: Archaeology Preserves What is Remembered and What is Forgotten in Israel's History," Journal of Biblical Literature 122/3 (2003), pp. 401-25. Wed. Sept. 7th Background: The Territory and the Neighborhood Fri. Sept. 9th The Egyptian New Kingdom Mon. Sept. 12th The Canaanites: Dan, Megiddo, & Lachish Wed. Sept. 14th The Philistines, part 1: Tel Miqne/Ekron & Ashkelon Fri. Sept. 16th The Philistines, part 2: Tel Qasile and Dor Mon. Sept. 19th The Israelites, part 1: 'Izbet Sartah Wed. Sept. 21st The Israelites, part 2: Mt. Ebal and the Bull Site Fri. Sept. 23rd Discussion day & short paper #1 due IRON AGE II: Nations and Narratives READING: Larry Herr, "The Iron Age II Period: Emerging Nations," Biblical Archaeologist 60.3 (1997), pp. 114-83; Seymour Gitin, "The Philistines: Neighbors of the Canaanites, Phoenicians, and Israelites," 100 Years of American Archaeology in the Middle East, D. R. Clark and V. H. Matthews, eds. (American Schools of Oriental Research, Boston: 2004), pp. 57-85; Judges 13:24-16:31; Steven Weitzman, "The Samson Story as Border Fiction," Biblical Interpretation 10,2 (2002), pp. 158-74; Azzan Yadin, "Goliath's Armor and Israelite Collective Memory," Vetus Testamentum 54.3 (2004), pp. 373-95. Mon. Sept. 26th The 10th century, part 1: Hazor and Gezer Wed. -

The Wofford Israel Trip Leaves on Friday, January 6, on a 15 Hour Flight from GSP, Through New York, and to Tel Aviv

Wofford's Israel Trip JANUARY 01, 2006 ISRAEL BOUND on JANUARY 6! The Wofford Israel trip leaves on Friday, January 6, on a 15 hour flight from GSP, through New York, and to Tel Aviv. With the 7 hour time difference, it will "seem" like a 22 hour flight. If you thought sitting through an 80' lecture from Dr. Moss was tough; wait til you try a 15 hour flight! [Of course, that includes a 3 hour lay-over in NY]. JANUARY 07, 2006 First Day In Israel Hi from Nazareth! We made it to Israel safely and with almost all of our things. It is great to be here, but we are looking forward to a good night's rest. We left the airport around lunchtime today and spent the afternoon in Caesarea and Megiddo. We had our first taste of Israeli food at lunch in a local restaurant. It was a lot different from our typical American restaurants, but I think we all enjoyed it. Caesarea is a Roman city built on the Mediterranean by Herod a few years before Jesus was born. The city contains a theatre, bathhouse, aqueduct, and palace among other things. The theatre was large and had a beautiful view of the Mediterranean. There was an aqueduct (about 12 miles of which are still in tact) which provided water to the city. The palace, which sits on the edge of the water, was home to Pontius Pilot after Herod s death. We then went to Megiddo, which is a city, much of which was built by King Solomon over 3000 years ago. -

Accents, Punctuation Or Cantillation Marks?

Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? A Study of the Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger Masteroppgave i SEM4090 Semittisk Språkvitenskap 60 studiepoeng Program: Asiatiske og afrikanske studier Studieretning: Semittisk språkvitenskap med hebraisk Instituttet for kulturstudier og orientalske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 1. juni 2012 II Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? A Study of the Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger (Proverbs 1:7) יִרְאַ ַ֣תיְְ֭הוָ ה רֵ אשִ ַ֣ ית דָ ָּ֑עַ ת III © Matthew Phillip Monger 2012 Accents, Punctuation or Cantillation Marks? The Linguistic Basis of the ṭəʿ Matthew Phillip Monger http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This thesis discusses different strategies for interpreting the placement of the ṭəʿ in Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible. After introducing the signs and their distribution in the text, the thesis looks at different levels of linguistic analysis where the ṭəʿ provide interesting information. At the word level, word stress and vowel length are discussed. At the phrase level, the different types of phrases are analyzed in light of a closest constituent analysis. At the verse level, the distribution of the ṭəʿ is shown to depend on simple rules which maximize the most common structures of Tiberian Hebrew. Prosodic structure is also evaluated to show what bearing that it has on the placement of the ṭəʿ . Finally, the ṭəʿ are discussed in relation to discourse features. The goal of the thesis is to show that the ṭəʿ are not simply musical notation, but have a linguistic basis, and provide insight into linguistic features of Tiberian Hebrew. -

The Open Torah Ark a Jewish Iconographic Type in Late Antique Rome and Sardis

chapter 6 The Open Torah Ark A Jewish Iconographic Type in Late Antique Rome and Sardis Steven Fine* Scholars have long noted that images of Torah Shrines are markedly different in the Land of Israel from those that appear in Jewish contexts in and around Rome (see Hachlili 1988, 166–87, 247–49, 270–80; 1998, 67–77, 363–73; 2000; 2013, 192–205 and references there). In Palestinian exempla—in mortuary contexts, reliefs, occasionally on a ritual object and especially on mosaic syna- gogue pavements—the doors of the cabinet are almost always closed. This is the case within both Jewish and Samaritan contexts (Meyers 1999; Magen 2008, 134–37; Hachlili 2013, 192–203; Figs. 6.1–6.3). Only one image of an ark contain- ing scrolls has been discovered in Israel, a rather primitive graffito found in the Jewish catacombs at Beth Sheʿarim (Hachlili 1988, 247), a burial compound known for having served Jews from both Palestine and the nearby Diaspora communities (Rajak 2001). By contrast, in Rome (Figs. 6.4–6.6), and in the Sardis synagogue in Lydia in Asia Minor (Fig. 6.7), the Torah Shrine is presented open, with scrolls exposed (Hachlili 1998, 362–67). Happily, Rachel Hachlili has handily collected and made available all of the extant evidence of Torah Shrines from both Israel and the Diaspora. Her corpora (1988; 1998) are now a touchstone for the study of this material, allowing all who have followed after her the luxury of a fully orga- nized body of sources, and readily available. This alone is a major accomplish- ment, one that I am pleased to celebrate with this chapter. -

Theological Monthly

Concoll~i(] Theological Monthly DECEMBER • 1959 The Theology of Synagog Architecture (As Reflected in the Excavation ReportS) By MARTIN H. SCHARLEMANN ~I-iE origins of the synagog are lost in the obscurity of the past. There seem to be adequate reasons for believing that this ~ religious institution did not exist in pre-Exilic times. Whether, however, the synagog came into being during the dark years of the Babylonian Captivity, or whether it dates back only to the early centuries after the return of the Jews to Palestine, is a matter of uncertainty. The oldest dated evidence we have for the existence of a synagog was found in Egypt in 1902 and consists of a marble slab which records the dedication of such a building at Schedia, near Alexandria. The inscription reads as follows: In honor of King Ptolemy and Queen Berenice, his sister and wife, and their children, the Jews (dedicate) this synagogue.1 Apparently the Ptolemy referred to is the one known as the Third, who ruled from 247 to 221 B. C. If this is true, it is not unreasonable to assume that the synagog existed as a religious institution in Egypt by the middle of the third century B. C. Interestingly enough, the inscription calls the edifice a :JtQOOE'UXY!, which is the word used in Acts 16 for something less than a per manent structure outside the city of Philippi. This was the standard Hellenistic term for what in Hebrew was (and is) normally known as no.pi'1 n~, the house of assembly, although there are contexts where it is referred to as i1~!:l~i'1 n::1, the house of prayer, possibly echoing Is. -

Jewish Book and Arts Festival

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 The Jewish Musical Permit No. 85 Urban Volunteers Theater Kibbutz and with Movement VNP Ari Axelrod page 16 page 19 page 21 October 2018 Tishrei/Cheshvan 5778 Volume XVIII Number 2 FREE Old world meets new world for the Arts Around Town: Jewish Book and Arts Festival Clara Silver, special to the WJN he Jewish Community Center of Friends of Magen David Adom at afmda.org/ On Thursday, Kahn’s unique contribution to the creation Greater Ann Arbor will present Arts event/talk-with-alan-dershowitz. October 25, the eve- of modern manufacturing as well as his role T Around Town: Jewish Book and Arts The annual Book and Gift Sale concur- ning will begin with in defending and preserving the famous Di- Festival beginning Thursday, October 18, rent with Arts Around Town will open the the annual sponsor ego Rivera mural at the Detroit Institute of and continuing through Monday, November same evening, Thursday, October 18, in the dinner at 6 p.m., for Art, and his role in helping the Soviets push 12. For 31 years the JCC has produced a fes- atrium of the JCC. A variety of books of those members of the back the Nazis in 1941–1942. tival — originally exclusively a book festival popular genres, as well as books from the Arts Around Town will host photographer — which has evolved to a broader festival presenters and authors who will be guest of Leslie Sobel on Sunday, October 29, for a recep- celebrating authors and artists of all kinds. -

Day One of the Omer Devotional

1 A STUDY ON THE RUACH HAKODESH AND HIS SPIRITUAL GIFTS Study One Isaiah 61:1-3 Isa 61:1 The Spirit of the Lord GOD (YHWH ELOHIM) is upon me, Because the LORD has anointed me To bring good news to the afflicted; He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, To proclaim liberty to captives And freedom to prisoners; Isa 61:2 To proclaim the favorable year of the LORD And the day of vengeance of our God; To comfort all who mourn, Isa 61:3 To grant those who mourn in Zion, Giving them a garland instead of ashes, The oil of gladness instead of mourning, The mantle of praise instead of a spirit of fainting. So they will be called oaks of righteousness, The planting of the LORD, that He may be glorified. Words To Ponder Ruach Strongs #7307 – H7307 רּוח rûach roo'-akh From H7306; wind; by resemblance breath, that is, a sensible (or even violent) exhalation; figuratively life, anger, unsubstantiality; by extension a region of the sky; by resemblance spirit, but only of a rational being (including its expression and functions): - air, anger, blast, breath, X cool, courage, mind, X quarter, X side, spirit ([-ual]), tempest, X vain, ([whirl-]) wind (-y). Anointed H4886 מׁשח mâshach maw-shakh' A primitive root; to rub with oil, that is, to anoint; by implication to consecrate; also to paint: - anoint, paint. shemen sheh'-men ׁשמן Oil - H8081 From H8080; grease, especially liquid (as from the olive, often perfumed); figuratively richness: - anointing, X fat (things), X fruitful, oil ([-ed]), ointment, olive, + pine. -

OJL AUGUST WEB.Pdf

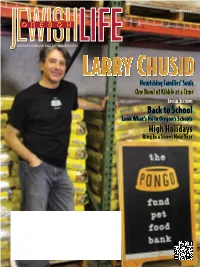

AUGUST 2013 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON Nourishing Families’ Souls One Bowl of Kibble at a Time SPECIAL SECTIONS BackBack toto SchoolSchool LookLook What’sWhat’s NuNu inin Oregon’sOregon’s SchoolsSchools HighHigh HolidaysHolidays RingRing inin aa SweetSweet NewNew YearYear A Place to Call our vision for the future HOME TRUSTWORTHY COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTIONS You’re Invited October 3rd, 2013 IDENTITY THEFT; How to protect yourself at home and overseas. visit our website or call to register for this complimentary event GRETCHEN STANGIER, CFP® WWW.STANGIERWEALTHMANAGEMENT.COM 9955 SE WASHINGTON, SUITE 101 • PORTLAND, OR 97216 • 877-257-0057 • [email protected] SECURITIES AND ADVISORY SERVICES OFFERED THROUGH LPL FINANCIAL. A REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISOR. MEMBER FINRA/SIPC. INVEST IN ISRAEL A Place to Call our vision for the future HOME 2013 · 5774 HIGH HOLIDAYS INVEST IN ISRAEL BONDS · ISRAELBONDS.COM Development Corporation for Israel/Israel Bonds This is not an offering, which can be made only by prospectus. Read the prospectus carefully Western Region before investing to fully evaluate the risks associated with investing in Israel bonds. Issues subject 4500 S. Lakeshore Drive, Suite 355 · AZ 85282 to availability. Member FINRA Photo Credits: pokku/Shutterstock.com; jvinasd/Shutterstock.com; 800.229.4324 · (fax) 480.948.7413 · [email protected] Nir Darom/Shutterstock.com; Noam Armonn/Shutterstock.com; Jim Galfund Table of Contents AUGUST 2013/ Av-Elul 5773 | Volume 2/Issue 7 [Cover Story] 28 Pongo Fund: Pet Food Bank Nourishes -

Handbook on Judaica Provenance Research: Ceremonial Objects

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America depositing Torah scrolls in a grave at Beth El Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 January 1952. Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBOOK ON JUDAICA PROVENANCE RESEARCH: CEREMONIAL OBJECTS By Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, and Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2018 Table of Contents Foreword, Wesley A. Fisher page 4 Disclaimer page 7 Preface page 8 PART 1 – Historical Overview 1.1 Pre-War Judaica and Jewish Museum Collections: An Overview page 12 1.2 Nazi Agencies Engaged in the Looting of Material Culture page 16 1.3 The Looting of Judaica: Museum Collections, Community Collections, page 28 and Private Collections - An Overview 1.4 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the West: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction page 43 1.5 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the East: The Soviet Trophy Brigades and Nationalizations in the East after World War II page 61 PART 2 – Judaica Objects 2.1 On the Definition of Judaica Objects page 77 2.2 Identification of Judaica Objects page 78 2.2.1 Inscriptions page 78 2.2.1.1 Names of Individuals page 78 2.2.1.2 Names of Communities and Towns page 79 2.2.1.3 Dates page 80 2.2.1.4 Crests page 80 2.2.2 Sizes page 81 2.2.3 Materials page 81 2.2.3.1 Textiles page 81 2.2.3.2 Metal page 82 2.2.3.3 Wood page 83 2.2.3.4 Paper page 83 2.2.3.5 Other page 83 2.2.4 Styles -

Ancient Synagogues in the Holy Land - What Synagogues?

Reproduced from the Library of the Editor of www.theSamaritanUpdate.com Copyright 2008 We support Scholars and individuals that have an opinion or viewpoint relating to the Samaritan-Israelites. These views are not necessarily the views of the Samaritan-Israelites. We post the articles from Scholars and individuals for their significance in relation to Samaritan studies.) Ancient Synagogues in the Holy Land - What Synagogues? By David Landau 1. To believe archaeologists, the history of the Holy Land in the first few centuries of the Christian Era goes like this: After many year of staunch opposition to foreign influence the Jews finally adopted pagan symbols; they decorated their synagogues with naked Greek idols (Hammat Tiberias) or clothed ones (Beth Alpha), carved images of Zeus on their grave (Beth Shearim), depicted Hercules (Chorazin) and added a large swastika turning to the left (En Gedi) to their repertoire, etc. Incredible. I maintain that the so-called synagogues were actually Roman temples built during the reign of Maximin (the end of the 3rd century and beginning of the 4th) as a desperate means to fight what the roman considered the Christian menace. I base my conclusion on my study of the orientations of these buildings, their decorations and a testimony of the Christian historian Eusebius of Caesaria. 2. In 1928, foundations of an ancient synagogue were discovered near kibbutz Beth Alpha in the eastern Jezreel Valley at the foot of Mt. Gilboa. Eleazar Sukenik, the archaeologist who excavated the site wrote (1932: 11): Like most of the synagogues north of Jerusalem and west of the Jordan, the building is oriented in an approximately southerly direction.