Regional Aviation Baseline Study Final Report May 2021 Regional Aviation Baseline Study Final Report May 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments to Paine Field Airport; They Have Been Noted

SnohoniLt 1) • 17’ 1 J ,4$~ic~ Comments Countvkitport u amer len ~F Environtuental Assessinen~ ~~S4LW, LOft. 9~t7f NSCtEwJ cn~, cc~c i2~k ~u u~ COMMENTS: A~ 4o~i-c ~M ~—Tw*~ C Ia Dave Waggoner Cayla Morgan Director Environmental Protection Spedalist Snohomish County Airport Seattle Airports District Office Comments to 3220 100th Street Southwest or Federal Aviation Administration Everett, Washington 98204 1601 Lind Avenue, SW Barnard Dunkelberg >? Company Email. [email protected] Renton, Washington 98057-3356 BridgeNet International Email. [email protected] Synergy Consultants Gibson Traffic Consultants Thank You! D.1 Response to Comment Dear Jeanne and George Dalton: Thank you for your comments to Paine Field Airport; they have been noted. D.2 -Original Message— From: [email protected] [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Wednesday, January 20, 2010 5:40 PM To: Waggoner, Dave; Dolan, Bill; Ryk Dunkelberg; Ryan Hayes Cc: [email protected]; [email protected]; Roland. J.McKee@faa . gov Subject: Fw: Paine Field review Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airports District Office Federal Aviation Administration 425—227—2653 Forwarded by Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA on 01/20/2010 04:38 PM I > From: I I > I > IStephen Dana <[email protected]> > > I To: I > I > Cayla Morgan/ANM/FAA@FAA I > > Date: I > > 101/20/2010 03:22 PM > > Subject: I > > IPaine Field review > D.3 January 19, 2010 Cayla Morgan Environmental Protection Specialist Seattle Airport District Office, FAA 1601 Lind Ave SW Renton, WA 98057 Ms. Morgan, The matter of commercial air service at Paine field is up for environmental review before your office in the coming weeks. -

Informational Handout: King County International Airport-Boeing Field Seattle, Washington

Informational Handout: King County International Airport-Boeing Field Seattle, Washington Published Visual Flight Rules (VFR) routes for arrivals and departures. Project Background The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) cancelled two existing VFR routes for aircraft landing and departing King County International Airport-Boeing Field (KBFI) and replaced them with newly defined routes (retaining some of the existing names). The term “routes” can best be described in this instance as a “set of pre-coordinated instructions” that is given to VFR pilots. The routes enhance safety by increasing separation between arrival and departure flows into KBFI, Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (KSEA), and Renton Municipal Airport (KRNT). Purpose of Changes There have been Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) events involving VFR aircraft arriving and departing KBFI, and these routes are intended to reduce TCAS events and enhance safety. TCAS monitors the airspace around an aircraft for other aircraft equipped with proper equipment, independent of air traffic control, and warns pilots of the presence of other properly equipped aircraft in the immediate area. Project Description The project results in a change to past operating procedures by publishing several existing routes for VFR aircraft to use when arriving and departing from either runway configuration at KBFI. KBFI Airport Traffic Control Tower (BFI ATCT) now has the ability to assign published routes rather than issuing tailored instructions. The new VFR routes provide better predictability, enhance safety, and improve the segregation of aircraft arriving and departing KBFI. What Changed The new VFR routes follow pre-existing air traffic flight tracks that are assigned by BFI ATCT and no new areas will experience new air traffic overflights. -

Forecasts of Aviation Activity

CHAPTER B Forecasts of Aviation Activity: Forecasting is a key element in any airport master planning process. The forecast process is essential for analyzing existing airport facilities and identifying further needs and requirements of the facilities that may arise over the next 20 years. The relationship between aviation activity and projected demand is an indicator as to the type, timing, and allocation of future airport infrastructure, equipment, and service needs. For the purposes of this Airport Master Plan, the most important element of the forecasts chapter is the documentation of existing aircraft operations by type and size of aircraft as well as the future projections of operations by type and size of aircraft. One of the assumed outcomes of this planning process was that the type and size of aircraft using the Airport on a regular basis are larger than what RNT was originally designed for. The trend of more operations by larger design aircraft is forecast to continue and warrants a design standard change for RNT. This change in design standards is further discussed starting on Page B.37 with the conclusion being that the Airport is, in fact, in need of a design standards upgrade in accordance with FAA guidance. Introduction. The RNT aviation activity forecasts in this chapter are developed for a 20-year planning period and are based on historic activity, industry trends, local socioeconomic data, and changes at RNT since the completion of previous planning studies. The forecasts utilize FY2015 (October 2014 through September 2015) as the base year and project future activity through 2035, identified in 5-year increments. -

(Asos) Implementation Plan

AUTOMATED SURFACE OBSERVING SYSTEM (ASOS) IMPLEMENTATION PLAN VAISALA CEILOMETER - CL31 November 14, 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service / Office of Operational Systems/Observing Systems Branch National Weather Service / Office of Science and Technology/Development Branch Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary............................................................................ iii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.......................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope.................................................................................... 2 1.4 Applicable Documents......................................................... 2 1.5 Points of Contact.................................................................. 4 2.0 Pre-Operational Implementation Activities ............................ 6 3.0 Operational Implementation Planning Activities ................... 6 3.1 Planning/Decision Activities ............................................... 7 3.2 Logistic Support Activities .................................................. 11 3.3 Configuration Management (CM) Activities....................... 12 3.4 Operational Support Activities ............................................ 12 4.0 Operational Implementation (OI) Activities ......................... -

Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study Next Steps

Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study Next Steps DAVID FLECKENSTEIN, AVIATION DIRECTOR Washington State Transportation Commission Meeting March 16, 2021 Planning for the Next Aviation Revolution • Electric aircraft are flying today and new companies are entering the market every day – Approximately 215 models under development • WSDOT completed a one year consultant led study on the potential impacts of electric aircraft for Washington State in November 2020 • This technology has the potential to open up new markets for air travel while reducing greenhouse gas emissions • Planning for implementation of electric aviation is key to successful adoption 2 Electric Aviation in Washington Washington State could become the epicenter for electric aircraft • Development • magniX, headquartered in Redmond, is developing the next generation of aircraft propulsion with its electric engines • Testing • AeroTEC is currently flight testing a Cessna Caravan converted to electric propulsion with a magniX engine at Grant County International Airport in Moses Lake • Manufacturing • Recently announced that Eviation plans to assemble the Alice at Arlington Municipal Airport o Alice utilizes the magniX engines 3 Washington Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study - Study Areas of Emphasis • Identification of current and projected airport infrastructure improvement needs to accommodate electric aircraft • Evaluation of projected economic impact resulting from increased access to air transportation • Demand forecasting for electric propulsion regional passenger air -

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

PAINE FIELD HANGAR UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024

FOR SALE PAINE FIELD HANGAR UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024 CONTACT US KATRIN GIST CBRE, Inc. Associate 10885 NE 4th Street +1 206 947 1399 Suite 500 [email protected] Bellevue, Washington 98004 www.cbre.com/bellevue FOR SALE PAINE FIELD HANGAR HANGAR FEATURES PRICE: $680,000 This 5,625 sq. ft. aircraft hangar is an attractive option for those looking for an alternative to Boeing Field. Recently built in 2007, the hangar still feels new and offers a comfortable build-out that could be used for a variety of aviation purposes. Serving as a general aviation, industrial and commercial airport for the North Puget Sound region only 29 minutes north of Seattle, Paine Field provides a wide variety of aviation and industrial facilities, services and activities. It is ideal for the Northwest aircraft owner/operator. + 75 ft. x 75 ft. + 22 ft. clear height + 75 ft. wide hydroswing door + Radiant heat + Insulated + High bay halogen lighting + Sprinkler fire suppression system + Electrical system including 100 amps: − 110 and 220V + Security card gate access + Includes 350 sq. ft. office, bathroom and shower + Ground lease through May 31, 2041 with 15 year extension option UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST Everett, Washington 98024 BUILDING D SITE PLAN BUILDING D FLOOR PLAN UNIT D103 Not to scale FOR SALE UNIT D103 9800 29TH AVENUE WEST PAINE FIELD HANGAR Everett, Washington 98024 AERIAL MAP 9800 29th AVENUE WEST UNIT D103 © 2015 CBRE, Inc. The information contained in this document has been obtained from sources believed reliable. While CBRE, Inc. -

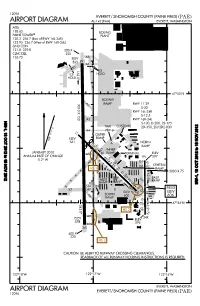

Airport Diagram Airport Diagram

12096 EVERETT/ SNOHOMISH COUNTY (PAINE FIELD) (PAE) AIRPORT DIAGRAM AL-142 (FAA) EVERETT, WASHINGTON ATIS 128.65 BOEING PAINE TOWER PLANT 120.2 256.7 (East of RWY 16L-34R) 132.95 256.7 (West of RWY 16R-34L) GND CON 121.8 339.8 200 X CLNC DEL 220 126.75 AA ELEV 16R 563 A1 K1 162.0^ ILS ILS HOLD HOLD A 47^55'N BOEING 9010 X 150 A2 RAMP RWY 11-29 S-30 RWY 16L-34R S-12.5 A3 RWY 16R-34L NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV S-100, D-200, 2S-175 TWR CUSTOMS 2D-350, 2D/2D2-830 11 A4 787 B .A OUTER ELEV RAMP VAR 17.1^ E 561 NORTH 117.0^ C RAMP INNER C1 JANUARY 2010 D1 RAMP TERMINAL ELEV A5 16L D-3 ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE D-3 4514 X 75 C 597 0.2^ W X G1 F1 A6 X D2 CENTRAL X G2 F2 HS 1 RAMP X D3 162.5^ X H D 3000 X 75 A X X X D40.9% UP G3 EAST WEST X X RAMP RAMP W3 X NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV FIRE F X STATION 297.0^ D5 FIELD K7 A7 E G4 ELEV F4 ELEV A8 SOUTH 29 600 606 RAMP G 342.5^ 47^54'N 342.0^ G5 A G6 HS 2 F6 A9 A 34R ELEV ELEV 578 596 A10 34L 400 X 220 HS 3 CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. -

Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 61 | Issue 4 Article 2 1996 Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne, Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization, 61 J. Air L. & Com. 793 (1996) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol61/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WOULD COMPETITION IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION EVER FIT INTO THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION? RUWANTISSA I.R. ABEYRATNE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 794 II. THE GENESIS OF AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS ......... 795 A. TiH CHICAGO CONFERENCE ...................... 795 B. THE CHICAGO CONVENTION ..................... 800 C. POST-CHICAGO CONVENTION TRENDS ............ 802 D. THiE BERMUDA AGREEMENT ...................... 805 E. Ti ROLE OF ICAO ............................. 808 III. RECENT TRENDS .................................. 809 A. THE AI TRANSPORT COLLOQUIUM .............. 809 B. POST-COLLOQUIuM TRENDS ...................... 811 C. THE WORLD-WIDE AIR TRANSPORT CONFERENCE. 814 D. SOME INTERIM GLOBAL ISSUES ................... 816 E. OBJECTWES OF THE CONFERENCE ................ 819 F. EXAMINATION OF ISSUES -

A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019

Airbus A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958-2019 Contents Scope and definitions 02 1.0 2020 & beyond 05 Accidents in 2019 07 2020 & beyond 08 Forecast increase in number of aircraft 2019-2038 09 2.0 Commercial aviation accidents since the advent of the jet age 10 Evolution of the number of flights & accidents 12 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 13 Impact of technology on aviation safety 14 Technology has improved aviation safety 16 Evolution of accident rates by aircraft generation 17 3.0 Commercial aviation accidents over the last 20 years 18 Evolution of the yearly accident rate 20 Ten year moving average of accident rate 21 Accidents by flight phase 22 Distribution of accidents by accident category 24 Evolution of the main accident categories 25 Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident rates 26 Loss Of Control In-flight (LOC-I) accident rates 27 Runway Excursion (RE) accident rates 28 List of tables & graphs 29 A Statistical Analysis of Commercial Aviation Accidents 1958 / 2019 02 Scope and definitions This publication provides Airbus’ a flight in a commercial aircraft annual analysis of aviation accidents, is a low risk activity. with commentary on the year 2019, Since the goal of any review of aviation as well as a review of the history of accidents is to help the industry Commercial Aviation’s safety record. further enhance safety, an analysis This analysis clearly demonstrates of forecasted aviation macro-trends that our industry has achieved huge is also provided. These highlight key improvements in safety over the factors influencing the industry’s last decades. -

JBLM Lark Monitoring Final Report 2015 W911S8-14-2-0026 W911S8-15-2-0001 CNLM Task Orders #G1108, G1118 April 2016

Habitat and Species Cooperative Restoration Program Joint Base Lewis-McChord Center for Natural Lands Management JBLM Lark Monitoring Final Report 2015 W911S8-14-2-0026 W911S8-15-2-0001 CNLM Task Orders #G1108, G1118 April 2016 Submitted to: Joint Base Lewis-McChord Fish and Wildlife Program Submitted by: Adrian Wolf, Gary Slater and Hannah Anderson Center for Natural Lands Management 120 Union Avenue Southeast Olympia WA, 98501 Phone: 360-584-2538 Joint Base Lewis-McChord is a key military installation and the most important conservation area in the Puget Trough region. The Center for Natural Lands Management strives to assist Joint Base Lewis-McChord in the conservation of its natural resources within the framework of the military training mandate. Joint Base Lewis- McChord and its conservation partners have shared interests because: Healthy natural ecosystems are essential for realistic and sustainable training lands. Rare species recovery throughout the region reduces the burden of recovery on any single landowner or site. Pest plants harm natural areas and reduce their suitability for military training. Page 2 Table of Contents Project Highlights ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Goals and Objectives ........................................................................................................... -

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams

Commercial Aviation Safety Team and Joint Safety Analysis Teams Raymond E. King, Psy.D. Major, USAF, BSC Chief, Research Branch HQ Air Force Safety Center Policy, Research, and Technology Division ABSTRACT Commission and the NCARC both The number of commercial airplanes in service recommended that, to find a way to reduce will nearly double by the year 2015, going from aviation accidents, the FAA work with the airline about 12,000 airplanes today to over 23,000 in industry to establish some form of strategic 2015. On a worldwide basis, the data suggest safety plan. nearly a hull loss accident per week by the year 2015 at the current accident rate, which has In 1997, at an NCARC hearing, FAA and airline plateaued over the last decade. Many ideas for industry representatives testified about how they enhancing safety focus on technology were investigating the root causes of aviation improvements to airplanes. While such accidents. The FAA Deputy Director of Aircraft improvements are important, it should be noted Certification Service, Beth Erickson, testified for that their impact would not be significant unless the agency: "We had learned from past efforts they can be implemented on the existing airplane that safety improvements were better fleet. A large portion of the airplanes that will be accomplished when we worked with competent operating in 2007 have already been built, and aviation authorities--pilot unions, airlines, most of the rest have already been designed. The aircraft and aerospace manufacturers, and so data show there are significant factors outside of forth--all pooling our expertise to come up with the airplane design itself that influence the the best way to deal with safety issues.