A Review of Multimedia Formats and Social Media Use for Traditional Radio Broadcasting in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rte Guide Tv Listings Ten

Rte guide tv listings ten Continue For the radio station RTS, watch Radio RTS 1. RTE1 redirects here. For sister service channel, see Irish television station This article needs additional quotes to check. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Найти источники: РТЗ Один - новости газеты книги ученый JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) RTÉ One / RTÉ a hAonCountryIrelandBroadcast areaIreland & Northern IrelandWorldwide (online)SloganFuel Your Imagination Stay at home (during the Covid 19 pandemic)HeadquartersDonnybrook, DublinProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishIrishIrish Sign LanguagePicture format1080i 16:9 (HDTV) (2013–) 576i 16:9 (SDTV) (2005–) 576i 4:3 (SDTV) (1961–2005)Timeshift serviceRTÉ One +1OwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannKey peopleGeorge Dixon(Channel Controller)Sister channelsRTÉ2RTÉ News NowRTÉjrTRTÉHistoryLaunched31 December 1961Former namesTelefís Éireann (1961–1966) RTÉ (1966–1978) RTÉ 1 (1978–1995)LinksWebsitewww.rte.ie/tv/rteone.htmlAvailabilityTerrestrialSaorviewChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Freeview (Northern Ireland only)Channel 52CableVirgin Media IrelandChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 135 (HD)Virgin Media UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 875SatelliteSaorsatChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Sky IrelandChannel 101 (SD/HD)Channel 201 (+1)Channel 801 (SD)Sky UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 161IPTVEir TVChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 115 (HD)Streaming mediaVirgin TV AnywhereWatch liveAer TVWatch live (Ireland only)RTÉ PlayerWatch live (Ireland Only / Worldwide - depending on rights) RT'One (Irish : RTH hAon) is the main television channel of the Irish state broadcaster, Raidi'teilif's Siranne (RTW), and it is the most popular and most popular television channel in Ireland. It was launched as Telefes Siranne on December 31, 1961, it was renamed RTH in 1966, and it was renamed RTS 1 after the launch of RTW 2 in 1978. -

Ringsend Arts Luas

Issue #12 Summer 2016. Published Whenever. INSIDE Meeja Gemma O'Doherty opens up about the need for outsider journalism... RTÉ A straight up look at why it's so bloody shit... Comics Yup, it's our usual array of full on miscreants and lovingly drawn eejits... BECKETT AND Gombeen BEHAN: TWO We finally get around to VERY DIFFERENT crucifying Ryan Tubridy in cutting prose... DUBLINERS Ringsend Arts Luas Are tech and global finance How the new rental realities Looking back at a history of remaking our city in their image? are killing all the DIY spaces... tram strikes in the capital... 2 Look Up {THE RANT} With the two month long back and forth discussions going on something Story? in the manner of Roger Federer playing squash by himself, even the mainstream HOWDY FOLKS. RABBLE’S media began to lose interest, the same BACK WITH THAT FRESH lads who cream themselves at even a SMELLING PRINTY EDITION sniff of an election. The media gave JUST IN TIME FOR fuck all scrutiny of the obvious lack SUMMER. SINCE YOU LAST of any programme for government, no CAUGHT UP WITH US scrutiny of the fact that the electorate THERE’S BEEN A GENERAL offered a resounding rejection of Fine ELECTION, A MONTH Gael’s austerity mode political and OF HARANGUING OVER barely batted an eyelid at the rhetoric {EYE} THE FORMATION OF THE of stability and recovery that was being choked out by Fine Gael pre-election. NEXT GOVERNMENT, THE Glimpses Of A Lost World. ACCELERATED GROWTH So rabble once again is here to dust down the dictionary and cut through Dragana Jurisic's journey as a photographer began when her family apartment was consumed with fire, taking OF AN UNPRECEDENTED the bullshit. -

17 Meán Fómhair, 2010 1 NUACHT NÁISIÚNTA Nuacht “Tá Seans Na Nóg

www.gaelsceal.ie Micheál Ó Laoch Muircheartaigh ag Litríochta éirí as - labhraíonn na nGael sé le Gaelscéal L. 7 Crann Beag L. 31 na nEalaíon L. 22 €1.65 (£1.50) Ag Cothú Phobal na Gaeilge 17.09.2010 Uimh. 26 • IDIRNÁISIÚNTA Gaeilge ag Athraithe Móra i ndán do SAM 30% de Seán Ó Curraighín, in Minnesota, SAM TÁ cuma ar chúrsaí go mbeidh athruithe móra pháistí na ar leagan amach na cumhachta sna Stáit Aontaithe sa toghchán lár téarma ag tús Samh- na. Tá na Poblachtaigh ar ríocht cumhacht a Gaeltachta bhaint amach i dTeach na nIonadaithe agus iad Anailís le Donncha Ó hÉallaithe Thart ar 10,000 teaghlach le gar don éacht céanna sa páistí scoile atá sa Ghaeltacht Seanad, dar le D’ÉIRIGH le 2,326 (70%) den 3,355 oifigiúil. 6,500 acu, ní bhacann pobalbhreith Washing- teaghlach Gaeltachta a rinne iar- siad le hiarratas a dhéanamh, mar ton Post-ABC. ratas faoi Scéim Labhairt na go dtuigeann a bhformhór nach In agallamh le Gaeilge, an deontas iomlán a fháil bhfuil a ndóthain Gaeilge ag a Gaelscéal, dúirt an tOl- anuraidh agus tugadh an deontas gcuid gasúr le cur isteach ar an lamh le hEolaíocht Pho- laghdaithe do 449 (13%) eile. scéim. laitiúil i UST, Minnesota, Nuair a deirtear ar an gcaoi sin é, Is é fírinne an scéil go léiríonn na Nancy Zingale, go gcaill- tá an chuma air go bhfuil líofacht figiúirí ón SLG 2009/10 go bhfuil fidh na Daonlathaigh Ghaeilge ag formhór na ndaltaí líofacht mhaith Ghaeilge ag thart cumhacht an tromlaigh i scoile sa Ghaeltacht. -

Heresa Morrow: RTÉ One TV: the Late Late Show: 8Th Jan 2016…………………………….81

Broadcasting Authority of Ireland Broadcasting Complaint Decisions September 2016 Broadcasting Complaint Decisions Contents BAI Complaints Handling Process Page 4 Upheld by the BAI Compliance Committee 26/16 - Mr. Francis Clauson: TV3: ‘The Power to Power Ourselves’ (Advert): 10th Jan 2016………………5 27/16 - Mr. Francis Clauson: RTÉ One TV: ‘The Power to Power Ourselves’ (Advert): 16th Jan 2016….…9 29/16 - Intro Matchmaking: Sunshine 106.8: Two’s Company (Advert):16th Feb 2016…………….………13 Rejected by the BAI Compliance Committee 7/16 - Mr. Brendan Burgess: RTÉ One TV: Ireland’s Great Wealth Divide: 21st Sept 2015……………….16 13/16 - Mr. Martin Hawkes: RTÉ One TV: Prime Time: 3rd Dec 2015……………………………………….23 15/16 - An Taisce: RTÉ One TV: Prime Time: 3rd Dec 2015………………………………………………….28 30/16 - Mr. Pawel Rydzewski: RTÉ One TV: The Late Late Show: 22nd Jan 2016…………………………38 32/16 - Mr Séamus Enright: TV3: TV3 Leaders’ Debate: 11th Feb 2016………………………………….…41 35/16 - Mr. John Flynn: RTÉ One TV: The Late Late Show: 19th Feb 2016…………………………………45 37/16 - Mr. Enda Fanning: RTÉ One TV: The Late Late Show: 19th Feb 2016……………………………48 Rejected by the Executive Complaints Forum 8-10/16 - Mr. Brendan O’ Regan: Newstalk: The Pat Kenny Show: 2nd – 4th Dec 2015……………………52 19/16 - Ms. Patricia Kearney: RTÉ Radio 1: When Dave Met Bob: 29th Dec 2015…………………………58 21/16 – Ms. Mary Jo Gilligan: RTÉ Radio 1: The Ray D’Arcy Show: 14th Nov 2015………………………61 22/16 - Mr. Brendan O’ Regan: Newstalk: Lunchtime: 30th Nov 2015…………………………………….…64 23/16 - Mr. Brendan O’ Regan: Newstalk: The Pat Kenny Show: 1st Dec 2015………………………….…64 25/16 - Mr. -

To Download the Joemaxi the Membership Fees Will Be €21 Per Week, of Which €20 Will App on the App Store Or Google Play

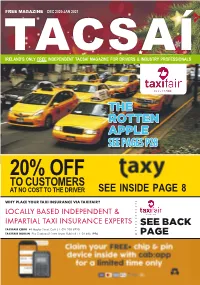

FREE MAGAZINE DEC 2020-JAN 2021 TACSAÍIRELAND’S ONLY FREE INDEPENDENT TACSAÍ MAGAZINE FOR DRIVERS & INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS THE ROTTEN APPLE SEE PAGES P28 20% OFF TO CUSTOMERS AT NO COST TO THE DRIVER SEE INSIDE PAGE 8 WHY PLACE YOUR TAXI INSURANCE VIA TAXIFAIR? LOCALLY BASED INDEPENDENTSEE PAGES & P2, 20, 40 & 55 Ben McArdle Limited T/A TaxiFair Insurance is IMPARTIAL TAXI INSURANCEregulated EXPERTS by Central BankSEE of Ireland. BACK TAXIFAIR CORK 48 Maylor Street, Cork | T: 021 203 8220 TAXIFAIR DUBLIN 21a Clanbrassil Street Lower, Dublin 8 | T: 01 485 1996 PAGE ALL EX-TAXI TRADE-INS WELCOME! IRELAND’S LARGEST USED TOYOTA The Hybrid PRIUS Motor Centre SUPPLIER! 2015s & ESTATE HYBRIDS AVAILABLE! The Hybrid Motor Centre is a supplier of used cars based in Rush, Co. Dublin. We specialise in fuel efficient cars ideal for the taxi trade. MODEL SHOWN: 2015 TOYOTA PRIUS 7-SEATER ESTATE We have over 100 cars in stock ALL OUR ADVERTISED CARS OUR CARS today! ARE ON OUR PREMISIS COME WITH A 2-YEAR WARRANTY CAN OTHERS MATCH THAT? MODEL SHOWN: 2015 TOYOTA PRIUS 7-SEATER ESTATE Call our sales team today: 01 870 2000 or 087 288 4146 WWW.HYBRIDMOTORCENTRE.IE The Hybrid Motor Centre, 60 Upper Main Street, Rush, Dublin CONTENTS ell the word on everyones the Taxi Advisory Committee and the group will lips is the same: Lockdown. keep drivers updated on this important issue. Taxi drivers in Ireland are We have also looked into the dire situation of really feeking the crunch as taxi drivers or “Cabbies” in New York City. -

Many Times in My Career in RTÉ, I Have Been Fortunate Enough to Feel Genuinely Proud of the Organisation, the Work We All Do and the Impact It Can Have

DirecTOR-GENERAL’S Review Many times in my career in RTÉ, I have been fortunate enough to feel genuinely proud of the organisation, the work we all do and the impact it can have. I certainly felt that during 2014. Not just because of the stand out programming, reporting and innovations RTÉ delivered across the year, but also because of the backdrop against which they were made. RTÉ has come through one of the most difficult and turbulent periods in its history. Over the past three years RTÉ has met, head on, the multiple challenges of editorial mistakes, dramatic falls in revenue, new competition and disruptive technology. Faced with these challenges, RTÉ has responded by developing a clear strategy to position the organisation for the long-term. We are now well on the way to evolving from a public service broadcaster to a public service media organisation relevant and essential to the increasingly digital lives of Irish people. The five-year strategy that TR É published in 2013 has set in train a period of change and renewal in RTÉ that continued apace during 2014. Everywhere you look in the organisation there are changes underway to meet the challenges we face. I can now say with confidence that our strategy is working. 2014 will be the second year running that RTÉ will achieve a small financial surplus, 6 Radio 1, lyric fm and 2fm, in addition to the station’s own news service. In parallel, online and on mobile we launched a national, international and I can now say with regional news service in Irish for the first time. -

Broadcasting Authority of Ireland Broadcasting Complaint Decisions

Broadcasting Authority of Ireland Broadcasting Complaint Decisions November 2017 Contents BAI Complaints Handling Process...………………………………………………………………………..3 Upheld in Part by the BAI Compliance Committee 57/17: Health Service Executive: WLR FM: Déise Today: 11/04/17…………………………………….4 Rejected by the BAI Compliance Committee 58/13: Mr. Patrick O’Connor: RTÉ One TV: Nationwide: 13/02/13……………………………...…….…9 21/15: Mr. Patrick O’Connor: RTÉ One TV: Nationwide: 15/12/14…………………………….……….14 61/16: Mr. Conor O’Shea: RTÉ One TV: Trailer – ‘Queen of Ireland’: 19/03/16………………...……20 63/16: Mr. Patrick O’Connor: RTÉ One TV: Trailer – ‘Queen of Ireland’: 18/03/16……………….….24 27/17: Mr. Kevin Dolan: RTÉ 2 TV: This is Ireland with Des Bishop: 22/12/16……………………….31 30/17: Mrs. Sharon Cooke: RTÉ One TV: Claire Byrne Live: 16/01/17……………………..…………36 39/17: Ms. Suzanne Gibbons: RTÉ One TV: Claire Byrne Live: 16/01/17………………….…………41 40/17: Animal Heaven Animal Rescue: RTÉ One TV: Claire Byrne Live: 16/01/17………...………..48 55/17: Mr. Conan Doyle: Newstalk: High Noon: 03/05/17………………………………………..……..54 Rejected by the Executive Complaints Forum 07/17: Gardasil Awareness Group: RTÉ Two TV: This is Ireland with Des Bishop: 12/12/16………58 08/17: Gardasil Awareness Group: RTÉ One TV: Prime Time: 24/11/16…………………………..…64 11/17: Dr. David Barnwell: RTÉ Radio One: Today with Seán O’Rourke: 23/01/17………………....69 12/17: Mr. Thomas A. Dowd: RTÉ One TV: The Late Late Show: 16/12/16………………………….72 16/17: Ms. Geraldine Heffernan: TV3: Ireland AM: 24/11/16…………………………………………...75 1 19/17: Mr. -

Manor St. John Christmas Newsletter 2018

Manor St. John Christmas Newsletter 2018 Read about from around the Wor summer memories & lots more The Board, Staff and all the Volunteers in Manor St. John Youth Service would like to wish all our members and their families a happy and peaceful Christmas. We also want to thank everyone who made our work with young people possible in 2018. Santa in Other Countries by Eve In Ireland, when we wake up on Christmas morning, Santa has our presents ready for us but what is it like in other countries? Do they believe in Santa or do they have their interpretation of him. We`ll see now. Christkind that went along with St. Nicholas on his journeys. He would bring presents to good children in Switzerland and Germany. He is angelic and is often drawn with blond hair and angel wings. People in Germany, Austria, Italy and Brazil believe in Christkind. Kris Kringle: There are two stories on the origin of Kris Kringle. The first one is that some one mispronounced Christkind and it stuck. The second one is that Kris Kringle began as Belsnickle among the Pennsylvania Dutch in the 1820s. He would ring his bell and give out nuts and cakes to the children but if they misbehaved they would get a spanking with his rod. The Yule Lads: The Yule Lads or Yulemen, are a group of thirteen mischievous creatures that have taken over Santa Claus in Iceland. They are known for their playful nature and each one has their own different, quite weird trick. For example, Ketkrokur uses a long hook to steal meat into people windows in order to find things to steal in the night. -

Disclosure Log of Completed Freedom of Information Requests

Disclosure Log of completed Freedom of Information requests 2018 Freedom of Information requests carried over and completed in January 2019 RTÉ Date FOI Freedom Of Information Request Requester Decision FOI No. Received 199. 21.11.2018 Journalist Granted in part. All documents (incl. memos, reports, correspondence), between RTÉ and Galway 2020, or their representatives, (including DG of RTÉ and Sections: 35(1)(a); 36(1)(b) and (c), 37(1). CEO of Galway 2020) pertaining to RTÉ’s partnership with Galway 2020 and the European Capital of Culture project, (between April 1, 2018 and October 31, 2018). 201. 03.12.2018 Journalist Granted in part. Guest costs for RTÉ chat shows in 2017: ‘Saturday Night with Miriam’, ‘The Late Late Show’, ‘The Ray D'Arcy Show’ and ‘The Sections: 35(1)(b); 36(1)(b) and (c). Cutting Edge’: taxi costs, hotel costs, flight costs, total fees, hairdressing and make-up, wardrobe and ‘Green Room’. Statutory Instrument SI 115 of 2000. 204. 21.11.2018 Member of the Granted in part. Copies of records (years 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017) showing numbers Public employed in RTÉ as: PAYE employees; contracted to RTÉ as self Section: 15(1)(a). employed individuals; under contract through companies. 209. 6.12.2018 Journalist Granted in part. Total cost of production of the 2018 ‘The Late Late Toy Show, The Greatest Showman’: breakdown of costs for: ‘Green Room’ Section: 36(1)(a) and (b). hospitality; Audience hospitality; travel costs for guests and for how many guests; security on the night and days leading up to the show. -

Irish Water Safety Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT Irish Water Safety, The Long Walk, Galway Tel: +353 (0)91 564400 Lo-Call: (within Ireland) 1890 420 202 (24 Hours) Fax: +353 (0) 91 564700 EMail: [email protected] www.iws.ie www.facebook.com/IWSie ©IWS. 2017 WEBSITES: www.iws.ie www.ringbuoys.ie www.aquaattack.ie www.iwsmembership.ie www.iwsmemberinsurance.com www.paws.iws.ie Michael D. Higgins, President of Ireland Patron of Irish Water Safety 1 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 2016 was a year of further growth and consolidation. Our membership has expanded signifi cantly to a point where at the time of writing we have 4,738 members nationwide. Further evidence of this growth is refl ected in the fact that 30 IWS Examiners and 106 IWS Instructors qualifi ed this year. The rate at which you, our members, are coming through the ranks has gone from strength to strength as volunteers teach swimming, lifesaving, basic life support, rescue skills and the promotion of water safety awareness to the public. The number of lives saved and aquatic accidents avoided as a result can never be fully enumerated although one fi gure that brings home the importance of your work is the number of rescues actioned by lifeguards each year, a fi gure that reached a total of 649 this summer. These same lifeguards, trained and assessed by Irish Water Safety, administered fi rst aid on 4,210 occasions and reunited with their loved ones, a total of 662 lost children found wandering alone by the water’s edge. If those numbers seem considerable then you will fi nd it signifi cant to note that on 29,695 occasions, lifeguards took specifi c actions to prevent an aquatic-related accident. -

Design a CEIST Award Competition All-Ireland CEIST Bake-Off Trinity

If you are experiencing difficulties viewing this email click here to view in your browser 28 November 2014 Training for School Boards of Management November brings to an end a very busy period for CEIST as it is during this month that training for new School Boards of Management takes place. CEIST had 33 new Boards taking up office last month. As well as visiting all new Boards at their first meeting, CEIST in conjunction with the JMB also encouraged Board members to participate in Board training, which took place on 15th, 22nd and 29th November at various locations throughout Ireland. A CEIST representative was present at all 9 venues and was involved in the delivery of the training. New Boards from other voluntary secondary schools are also present on the day so each event attracts a large gathering. Hour of Code The Hour of Code will take place during the week of Design a CEIST Award Competition Dec 8th - 14th in schools all over the world. We are inviting CEIST schools to participate in designing a Following on from "EU perpetual CEIST Award. Each school is asked to organise a Code week", during which competition within their school in the coming weeks with a Ireland arranged more view to inviting students to submit entries for this award. coding events than any other country in the EU, The actual design can be based on any medium for example this provides an opportunity sculpture, artwork, etc. The winning design from each school for teachers and students to be submitted via email to [email protected], (please alike to try coding. -

Raidió Teilifís Éireann Annual Report & Group Financial Statements 2011 Raidió Teilifís Éireann

Raidió Teilifís ÉiReann annual RepoRT & GRoup financial sTaTemenTs 2011 Raidió TeilifíS Éireann Highlights 1 Organisation Structure 2 What We Do 3 Chairman’s Statement 4 Director-General’s Review 6 Operational Review 10 Financial Review 40 Board 46 Executive 48 Corporate Governance 50 Board Members’ Report 54 Statement of Board Members’ Responsibilities 55 Independent Auditor’s Report 56 Financial Statements 57 Accounting Policies 64 Notes forming part of the Group Financial Statements 68 Other Reporting Requirements 103 Other Statistical Information 116 Financial History 121 RTÉ’S vision is to grow the TRust of the peoplE of Ireland as IT informs, inspires, reflects and enriches their lIvES. RTÉ’S mission is to: • NuRTure and reflect the CulTural and regional diversity of All the peoplE of Ireland • Provide distinctivE programming and services of the highest quAlITy and ambition, WITH the emphasis on home production • Inform the Irish PuBlic By delIvering the best comprehensivE independent news service possiblE • ENABlE national participation in All MAjor Events Raidió Teilifís Éireann Board 51st Annual Report and Group Financial Statements for the 12 months ended 31 December 2011, presented to the Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources pursuant to section 109 and 110 of the Broadcasting Act 2009. Is féidir leagan Gaeilge den Tuarascáil a íoslódáil ó www.rte.ie/about/annualreport ANNuAl REPORT & GROuP FINANCIAl STATEMENTS 2011 HiGHliGHTs Since 2008 RTÉ has reduced its operating costs by close to 20% or €86 million. RTÉ continues to be Ireland’s With quality home-produced leading provider of digital programming and the best content with the country’s acquired programming from most popular Irish owned overseas, RTÉ increased its live website, the most popular peak-time viewing share on on-demand video service RTÉ One to 30.9% in 2011.