Makarand Paranjape.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10-13, 2017

Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10 - 13, 2017 On August 10 - 13, 2017 the Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta was hosted by T he Center for Indic Studies, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, USA in collaboration with the Institute of Advanced Sciences, Dartmouth, USA . The inauguration session started in the morning of first day with Vedic c hanting performed by Swami Yogatmananda, Vedanta Society of Providence, and Swami Atmajnanananda, Vedanta Center of Greater Washington , DC . Welcome address and i ntroduction presented by Conference Director Prof. Sukalyan Sengupta, University of Massachusetts , Dartmouth. Founding Director, Vedanta Congress Prof. S.S. Ramarao Pappu was felicitated in this session. Conference started with an inaugural l ecture by Mr. Rajeev Srinivasan on “ Leveraging the Grand Dharmic Narrative for Soft Power ”. Dr. Alex Hankey, SVYASA Bangalore and Dr. Makarand Paranjape, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New D elhi were the keynote speakers during this inaugural session . They deliver ed their talk s on “ Synthesizing Vedic and Modern Theories to Explain Cognition of Forms ” and “ Vedanta and Aesthetics ” , respectively. This session was concluded under the chairmanship of Prof. Raghwendra P . Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Inaugural Session, 23 rd International Vedanta Congress The Vedanta Congress continues its tradition of bringing scholars of Indic traditions from India and the West together on a platform nearly from three decades. Delegates from various -

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

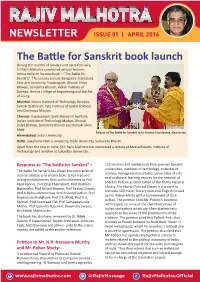

The Battle for Sanskrit Book Launch

NEWSLETTER ISSUE 01 | APRIL 2016 The Battle for Sanskrit book launch During the months of January and early February, Sri Rajiv Malhotra conducted various lectures across India on his new book – “The Battle for Sanskrit”. The venues include Bangalore: Karnataka Samskrit University, Yuvabrigade, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati, Indian Institute of Science, Amrita College of Engineering and the Art of Living. Mumbai: Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Samskrita Bharati, Tata Institute of Social Sciences and Chinmaya Mission. Chennai: Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati and Ramakrishna Mutt. Release of The Battle for Sanskrit at Sri Krishna Vrundavana, New Jersey Ahmedabad: Indus University. Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi University, Samskrita Bharati. Apart from the tour in India, Shri Rajiv Malhotra has conducted a lecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another at Columbia University. Response to “The Battle for Sanskrit”:- 132 scholars and intellectuals from premier Sanskrit universities, institutes of technology, institutes of The Battle for Sanskrit has drawn the admiration of science, management institutes, universities of arts several scholars and intellectuals. It has received and traditional learning centres for the removal of strong endorsements from such luminaries as Prof Sheldon Pollock as Chief Editor of the Murty Classical Kapil Kapoor, Prof Dilip Chakrabarti, Prof Roddam Library. The Murty Classical Library is a project to Narasimha, Prof Arvind Sharma, Prof Pankaj Chande, translate 500 Indian literary texts into English funded Prof K Ramasubramanian, Prof R Vaidyanathan, Prof by Mr. Rohan Murty with a commitment of $5.6 Dayananda Bharghava, Prof S.R. Bhatt, Prof K.S. -

The Case for Sanskrit As India's National Language by Makarand

The Case for Sanskrit as India’s National Language By Makarand Paranjape August 2012 This paper discusses in depth the role and the potential of Sanskrit in India’s cultural and national landscape. Reproduced with the author’s permission, it has been published in Sanskrit and Other Indian Languages , ed. Shashiprabha Kumar (New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2007), pp. 173- 200. “Sanskrit is the thread on which the pearls of the necklace of Indian culture are strung; break the thread and all the pearls will be scattered, even lost forever.” Dr. Lokesh Chandra Introduction I had first heard from my friends in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, that the Mother wanted Sanskrit to be made the national language of India. Indeed, Sanskrit is taught from childhood not only in the ashram schools, but also at Auroville, the comm unity that the Mother founded. On 11th November 1967, the Mother said: “ Sanskrit! Everyone should learn that. Especially everyone who works here should learn that….” 1 Because some degree of confusion persisted over the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s views on the topic, a more direct question was put to the former on 4 October 1971: On certain issues where You and Sri Aurobindo have given direct answers, we [Sri Aurobindo's Action] are also specific, as for instance... on the language issue where You have said for the country that (1) the regional language should be the medium of instruction, (2) Sanskrit should be the national language, and (3) English should be the international language. Are we correct in giving these replies to such questions? Yes. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita”

ICPR NATIONAL SEMINAR ON “SRI RAMAKRISHNA KATHAMRITA”, Indian Council of Philosophical Research (ICPR) has decided to organize a 3- day National Seminar on “Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita”. The seminar will be held at India International Centre, New Delhi. The tentative dates will be during 21-23 February, 2018. Those interested are invited to present well researched learned papers on a suitable topic relating to the theme as indicated in the enclosed theme note and submit the same to the undersigned latest by 31 January, 2018. Dr.Ranjan K. Ghosh (M) 9810395394; e-mail:<[email protected] Director, National Seminar on “Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita” THREE DAY NATIONAL SEMINAR ON SRI RAMAKRISHNA KATHĀMŖITA (Theme Note) Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita or The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna is a recorded conversation of Sri Ramakrishna (1836-1886 AD) – a spiritual Master of Bengal – with his disciples, devotees and visitors. Mahendranath Gupta, an intimate disciple of Sri Ramakrishna under the pseudonym of “M”, recorded in writing the Master’s day-to-day life along with his spiritual conversation with almost stenographic accuracy from February 1882 to April 1886, which is partially reminiscent of Socrates’ dialogue with his disciples, each of which conversations was recorded by their intimate disciples, namely, Mahendranath Gupta and Plato respectively. The contents of these conversations were deeply mystical in nature in the sense that these sayings described the inner spiritual experiences of Sri Ramakrishna. As a close disciple of Sri Ramakrishna, Mahendranath Gupta has brought out in his recording the thought-provoking deeper dimension of the simple and intimate utterances of the great prophet in the light of ancient scriptures of India especially the Vedanta. -

Professor Makarand Paranjape Currently Holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore

The Center for the Study of Hindu Traditions, University of Florida presents The Relevance of Gandhi to Environmental Studies by Professor Makarand Paranjape Professor Makarand Paranjape currently holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore. He is also Professor of English, Centre for English Studies, School of Language, Literature, and Culture Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Professor Paranjape has held a number of fellowships in several universities; he was previously the Homi Bhabha Fellow for Literature in India; Shastri Indo-Candian Research Fellow, University of Calgary; IFUSS Fellow, University of Iowa; Mellon Fellow, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; and Shivdasani Visiting Fellow, Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, University of Oxford. He has also been a Visiting Professor at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona and the Universitat des Sarlandes. Professor Paranjape will also be leading a class discussion on Hindu Traditions in Singapore (April 11, 2:30 pm, Room 117, Anderson Hall) Professor Paranjape is the author or editor of several books including Decolonization and Development: Hind Svaraj Revisioned (1993); Nativism: Essays in Literary Criticism (Sahitya Akademi, 1997); In Diaspora: Theories, Histories, Texts, Editor (2001); Sacred Australia: post-secular considerations (2009); Altered Destinations: Self, Society, and Nation in India (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); as well as the author of several volumes of poetry and fiction.. -

Raja Rao and the Politics of Truth

Lingue e Linguaggi Lingue Linguaggi 13 (2015), 227- ISSN 2239-0367, e-ISSN 2239-0359 DOI 10.1285/i22390359v13p227 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2015 Università del Salento FROM INDIANNESS TO HUMANNESS: RAJA RAO AND THE POLITICS OF TRUTH STEFANO MERCANTI UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE Abstract – Raja Rao is not merely a metaphysical writer, as many scholars of the first Commonwealth generation depict him as being, but rather a much more complex one whose literary dimensions transcend the commonplace essentializing ‘Hinduness’ projected by many critics over three decades. I thus suggest instead an amplification of Rao’s idea of India by framing his novels in a cross-cultural space which evolves during the course of his entire oeuvre on both philosophical and political levels. This dynamic ambivalence has its foremost predecessor in Mahatma Gandhi’s politico-spiritual legacy, Satyagraha (‘the force of Truth’) which becomes the centripetal and cohesive force of Raja Rao’s fiction. Keywords: Indianness; partnership model; Mahatma Gandhi; Indian English literature. Raja Rao is known to have given birth to the Indian English novel as an expression of a precise ideological re-construction of India’s racial, philosophical, cultural and linguistic specificities. His work asserted itself on the inter-national scene, and especially in a trans- national way, due to the originality of an idea of India capable of communicating with the West even through images and life styles distinctively indigenous. However, because of this extraordinary celebration of India’s native cultural distinctiveness, Raja Rao has been often ossified within the cultural construct of a universalistic Indian identity, an Indianness quintessentially and metaphysically Hindu, thus blurring the complexities and making exotic Indian geography and culture. -

Bhakti: a Bridge to Philosophical Hindus

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2000 Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus N. Sharath Babu Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Babu, N. Sharath, "Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus" (2000). Dissertation Projects DMin. 661. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/661 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS by N. Sharath Babu Adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS Name of researcher: N. Sharath Babu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister, Ed.D. Date completed: September 2000 The Problem The Christian presence has been in India for the last 2000 years and the Adventist presence has been in India for the last 105 years. Yet, the Christian population is only between 2-4 percent in a total population of about one billion in India. Most of the Christian converts are from the low caste and the tribals. Christians are accused of targeting only Dalits (untouchables) and tribals. Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation, advised Christians to direct conversion to those who can understand their message and not to the illiterate and downtrodden. -

Sri Sai Baba National Degree College (Autonomous) Accredited @ 'A' Level by Naac "College with Potential for Excellence" Status by Ugc Anantapur

SRI SAI BABA NATIONAL DEGREE COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) ACCREDITED @ 'A' LEVEL BY NAAC "COLLEGE WITH POTENTIAL FOR EXCELLENCE" STATUS BY UGC ANANTAPUR BOOKS AVAILABLE FOR REFERENCE S.No Book Id Book Title Author Publisher 1 014011 KAVITHALA SAMPUTAMU GURAJADA APPA RAO 2 014012 RACHAYITHA SHILPAMU ILYA EHRAN BURG 3 014013 MADHYE MADHYE N.UMA MAHESWARA RAO 4 014014 PADAVA PRAYANAMU PALAGUMMI PADMA RAJU 5 014015 REKHA CHITRALU S.V. 6 014016 SAHITHYA TATHVAMU R.V.R 7 014017 CHASO KATHALU CHAGANTI SOMAYAJULU 8 014018 ARNAD KATHALU ARNAD 9 014019 TELUGU GAJALS DR.C.NARAYANA REDDY 10 014020 SOUNDARA NANDAMU RAVURI BHARDWAJA 11 014021 VIVIAHAMU CHALAM 12 014022 MA GOKHALE KATHALU M.GOKHALE 13 014023 VEYI PADAGALU ADHUNIKA ITHIHSAMU DR.A.BHUMAIAH 14 014024 JIVITHAMU - SAHITHYAMU KOMPELLA JANARDHANA RAO 15 014025 NIJAMU RACHAKONDA VISWANATHA SASTRY 16 014026 MADHURA VANI ADAVI BAPI RAJU 17 014027 MALAPALLI - PRATHAMA SAMPUTI UNNAVA LAKSHMI NARAYANA 18 014028 MALAPALLI - DWITHIYA SAMPUTI UNNAVA LAKSHMI NARAYANA 19 014029 SATHYAM-SHIVAM-SUNDARAM CHALAM 20 014030 SRI MAHA BHAGAVATHAMU MODATI BHAGAMU ACHARYA RAYAPROLU SUBBA RAO 21 014031 SRI MAHA BHAGAVATHAMU RENDAVA BHAGAMU ACHARYA RAYAPROLU SUBBA RAO 22 014032 RAGHUVAMSAMU - MODATI BHAGAMU K.NARASIMHA SASTRY 23 014033 AMUKTHA MALYADA N.RAMADASAIAH 24 014034 SRI MADRAMAYANA KALPA VRUKSHAMU VISWANATHA SATHYA NARAYANA 25 014074 VASTHU SASTRA VASTAVALU GOWRU THIRUPATHI REDDY 26 014076 THE CONCISE OXFORD DICTIONERY 27 014349 SRIMAN MAHABHARATHAM-UDYOGA PARVAM ACHARYA SANKARA PRATHAMA BHAGAMU RAGHUNATHA SARMA -

Trailanga - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

ַטִאַילְנג ְסָוואִמי ترايﻻنغا سوامي تريلينگا http://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D9%81%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%B3%D8%AA_%D8%AD%D8%B2%D 8%A8%E2%80%8C%D9%87%D8%A7_%D8%AF%D8%B1_%D9%87%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%88%D 8%B3%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%86 سوامی Trailanga - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trailanga Trailanga From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Trailanga Swami (also Tailang Swami , Telang Swami ) [nb 1] [2] [2][3] Swami Ganapati Saraswati (Telugu: cంగ ాI ) (reportedly 1607 – 1887 ) was a Hindu yogi famed for his spiritual powers who lived in Born Shivarama Varanasi, India.[2] He is regarded as a legendary figure in 1607 Bengal, with many stories told about his yogic powers and Vizianagaram longevity. According to some accounts, Trailanga Swami Died December 26, 1887 (aged 280) [2][4] lived to be 280 years old, residing at Varanasi between Varanasi 1737-1887. [3] He is regarded by devotees as an incarnation of Shiva. Ramakrishna referred to him as the "The walking Titles/honours known as "The walking Shiva of Varanasi" Shiva of Varanasi". [5] Guru Bhagirathananda Saraswati Philosophy Dashanami Contents 1 Life 2 Death 3 Legends and stories 4 Teachings 5 Notes 6 References 7 References 8 Further reading 9 External links Life A member of the Dashanami order, he became known as Trailanga Swami after he settled in Varanasi. His biographers and his disciples differ on his birth date and the period of his longevity. According to one disciple biographer, he was born in 1529, while according to another biographer it was 1607. -

1 the Third Eye and Two Ways of (Un)Knowing: Gnosis, Alternative

1 The Third Eye and Two Ways of (Un)knowing: Gnosis, Alternative Modernities, and Postcolonial Futures By Makarand Paranjape Professor of English, JNU, New Delhi 110067 Presented at the Infinity Colloquium, 24-29 July 2002, New York The starting point for this paper is the premise that alternatives to modern epistemology can hardly come from modern (Western) epistemology itself. This idea has been voiced quite forcefully in recent thinking by scholars such as Walter D. Mignolo s, from whose book Local Histories/Global Designs the above phrase is taken. But even if we were to agree with such a premise, it still begs the question of where to look for these alternatives. For critics such a Mignolo, the challenge is to rehabilitate subaltern knowledge systems so as to bring about, to invoke a phrase from Foucault, an insurrection of subjected knowledges. Gnosis, gnoseology and border thinking have been used to describe these knowledge systems that are on the margins of or outside the world colonized by Western modernity. My project is to oppose the dominance of rationality (or, more recently, irrationality) in modern and postmodern philosophy by invoking ideas of the supra-rational from Classical as well as modern traditions of thinking, especially in India. These traditions, for lack of a better word, may be called wisdom traditions. That they share something with gnosticism should be obvious. I would like to focus on the work of one modern Indian thinker, Sri Aurobindo, particularly his idea of the Supermind, to suggest a slightly different way of conceiving postcolonial futures. Sri Aurobindo s thought has important implications for the discipline of consciousness studies because it posits the naturalization of a higher conscious than the mental.