Phd Thesis-Final Final Work for Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malkhuyot Sources Uhrbach.Pdf

אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא ... ואמרו לפני בראש השנה מלכיות זכרונות ושופרות מלכיות כדי שתמליכוני עליכם זכרונות כדי שיעלה זכרוניכם לפני לטובה ובמה בשופר כת' רבי' סעדיה מה שצונו הבורא יתברך לתקוע בשופר בראש השנה יש בזה עשרה ענינים. הענין הראשון מפני שהיום היתה תחלת הבריאה שבו ברא הקב"ה את העולם ומלך עליו וכן עושים המלכים בתחלת מלכותם שתוקעים לפניהם בחצוצרות ובקרנות להודיע ולהשמיע בכל מקום התחלת מלכותם וכן אנו ממליכין עלינו את הבורא ליום זה וכך אמר דוד בחצוצרות וקול שופר הריעו לפני המלך ה'. והטעם שתקנו לומר מראש השנה ועד יום הכפורים המלך במקום האל לפי שמראה מלכותו על בני העולם ששופט אותם בימים אלו אֵ ין מַ זְכִּירִ ין זִכְרוֹנוֹת מַ לְכֻיּוֹת וְ שׁוֹפָ רוֹת שֶׁ ל פֻּרְ עָ נוּת. זִכְ רוֹנוֹת כְּגוֹן )תהילים עח לט( "וַיִּזְכֹּר כִּי בָשָׂ ר הֵמָּ ה" וְ כוּ'. מַ לְכֻיּוֹת כְּגוֹן )יחזקאל כ לג( ה"בְּחֵמָ שְׁ פוּכָה אֶמְ לוְֹך ֲעֵליֶכם". שֹׁוָפרֹות ְכּגֹון )הושע ה ח( "ִתְּקעוּ שֹׁוָפר בַּגִּבְעָ ה" וְ כוּ'. ְוֹלא ִזְכרֹוָן יִחידֲאִפלּוּ ְלטֹוָבה ְכּגֹון )תהילים קו ד( "ָזְכֵרִני ה' ִבְּרצֹון ַעֶמָּך". )נחמיה ה יט( )נחמיה יג לא( "ָזְכָרה ִלּיֱ אֹלַהי ְלטֹוָבה". וִּפְקדֹונֹותֵאיָנן ְכִּזְכרֹונֹות. ְכּגֹון )שמות ג טז( "ָפֹּקד ָפַּקְדִתּיֶאְתֶכם". ְוֵישׁ לֹו ְלַהְזִכּיר ֻפְּרָענוֶּת שׁלֻאמֹּוַת עכּוּ''ם ְכּגֹון )תהילים צט א( "ה' מָ לְָך יִ ְרְגּזַוּ עִמּים". )תהילים קלז ז( "ְזֹכר ה' ִלְבֵניֱ אדֹוםֶאת יֹוְם ירָוּשָׁלִם".)גמרא ראש השנה לב ב( " ַוה'ֱ אֹלִהים ַבּשֹּׁוָפרִ יְתָקע ְוָהַלְך ְבַּסֲערֹות ֵתּיָמן". )דברים ו ד( ְ"שַׁמִעיְשָׂרֵאל ה'ֱ אֹלֵהינוּ ה' ֶאָחד". )דברי ם ד לה( ַ"אָתּה ָהְרֵאָת ָלַדַעת" ְוכ וּ'. )דברים ד לט( "ְוָיַדְעָתּ ַהיֹּום ַוֲהֵשֹׁבָת ֶאל ְלָבֶבָך" ְוכוּ'. ָכּל ָפּסוּקֵ מֵאלּוַּמְלכוּ ת הִוּא עְנָינֹו ַאַף על ִפּיֶשֵׁאין בֹּו ֵזֶכרַמְלכוּת ַוֲהֵרי הוּא ְכּמֹו )שמות טו יח( "ה'ִ יְמלֹוְך ְלעֹוָלם ָוֶעד", )דברים לג ה( "ַוְיִהי ִבֻישׁרוּןֶ מֶלְך" ְוכוּ ': ותמצא באלו השלשה ובכן ובכן ובכן רמז למלכיות זכרונות ושופרו ת כי הראשון הוא ובכן תן פחדך ה' אלקינו וייראוך כל המעשים ויעשו כלם אגודה אחת כנגד מלכיות כי כל זה ענין הממלכה שממליכין אותו. -

Psalm 34 Author and Date

Psalm 34 Title: The Lord Delivers the Righteous Author and Date: David Key Verses: Psalm 34:4, 7, 17, 19 Type: Thanksgiving Outline A. Thanksgiving: I will bless with a song because the Lord delivers (verses 1-10). B. Teaching: I will teach with a sermon because the Lord delivers (verses 11-22). Notes Title: “A Psalm of David.” See the notes on Psalm 3. “Who changed his behavior before Abimelech, who drove him away, and he departed.” This incident may be the one recorded in 1 Samuel 21:10-22:2 where David feigned madness before King Achish of Gath so that he would be left alone. Some commentators believe that “Abimelech” (meaning father of a king) is inaccurate, while others believe this name was a generic, dynastic title (like Pharoah) of the kings of Gath. Verses 1-22: This psalm is one of nine alphabetic acrostic psalms: Psalm 9, 10, 25, 34, 37, 111, 112, 119, and 145 (see the notes for Psalm 9, 10, and 25). The first word of each verse begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph, beth, gimel, daleth, etc.). There are 22 verses just like the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. However, in this psalm two letters (the Hebrew letter he and vav) are used in one verse (verse 5) and another letter (the Hebrew letter pe) is repeated (in verse 16 and 22) which make for 22 verses. Psalm 34 describes the Lord as a deliverer, a savior, and a redeemer of the righteous. Verse 5: Note that the psalmist switches abruptly from “I” to “they” in this verse. -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.Indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor

Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 1 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor. Hadesh. Yameinu RENEW OUR DAYS A Prayer-Cycle for Days of Awe Edited and translated by Rabbi Ron Aigen Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 3 18-08-29 11:38 Acknowledgments and copyrights may be found on page x, which constitutes an extension of the copyright page. Copyright © !""# by Ronald Aigen Second Printing, !""# $ird Printing, !""% Fourth Printing, !"&' Original papercuts by Diane Palley copyright © !""#, Diane Palley Page Designer: Associès Libres Formatting: English and Transliteration by Associès Libres, Hebrew by Resolvis Cover Design: Jonathan Kremer Printed in Canada ISBN "-$%$%$!&-'-" For further information, please contact: Congregation Dorshei Emet Kehillah Synagogue #( Cleve Rd #!"" Mason Farm Road Hampstead, Quebec Chapel Hill, CANADA NC !&)#* H'X #A% USA Fax: ()#*) *(%-)**! ($#$) $*!-($#* www.dorshei-emet.org www.kehillahsynagogue.org Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 4 18-08-29 11:38 Mahzor - Fourth Edition.indb 6 18-08-29 11:38 ILLUSTRATIONS V’AL ROSHI SHECHINAT EL / AND ABOVE MY HEAD THE PRESENCE OF GOD vi KOL HANSHEMAH T’HALLEL YA / LET EVERYTHING THAT HAS BREATH PRAISE YOU xxii BE-ḤOKHMAH POTE‘AḤ SHE‘ARIM / WITH WISDOM YOU OPEN GATEWAYS 8 ELOHAI NESHAMAH / THE SOUL YOU HAVE GIVEN ME IS PURE 70 HALLELUJAH 94 ZOKHREINU LE-ḤAYYIM / REMEMBER US FOR LIFE 128 ‘AKEDAT YITZḤAK / THE BINDING OF ISAAC 182 MALKHUYOT, ZIKHRONOT, SHOFAROT / POWER, MEMORY, VISION 258 TASHLIKH / CASTING 332 KOL NIDREI / ALL VOWS 374 KI HINNEI KA-ḤOMER / LIKE CLAY IN THE HAND OF THE POTIER 388 AVINU MALKEINU -

The Psalms As Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A

4 The Psalms as Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A. Rendsburg From as far back as our sources allow, hymns were part of Near Eastern temple ritual, with their performers an essential component of the temple functionaries. 1 These sources include Sumerian, Akkadian, and Egyptian texts 2 from as early as the third millennium BCE. From the second millennium BCE, we gain further examples of hymns from the Hittite realm, even if most (if not all) of the poems are based on Mesopotamian precursors.3 Ugarit, our main source of information on ancient Canaan, has not yielded songs of this sort in 1. For the performers, see Richard Henshaw, Female and Male: The Cu/tic Personnel: The Bible and Rest ~(the Ancient Near East (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1994) esp. ch. 2, "Singers, Musicians, and Dancers," 84-134. Note, however, that this volume does not treat the Egyptian cultic personnel. 2. As the reader can imagine, the literature is ~xtensive, and hence I offer here but a sampling of bibliographic items. For Sumerian hymns, which include compositions directed both to specific deities and to the temples themselves, see Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps that Once ... : Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 99-142, 375--444. Notwithstanding the much larger corpus of Akkadian literarure, hymn~ are less well represented; see the discussion in Alan Lenzi, ed., Reading Akkadian Prayers and Hymns: An Introduction, Ancient Near East Monographs (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 56-60, with the most important texts included in said volume. For Egyptian hymns, see Jan A%mann, Agyptische Hymnen und Gebete, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999); Andre Barucq and Frarn;:ois Daumas, Hymnes et prieres de /'Egypte ancienne, Litteratures anciennes du Proche-Orient (Paris: Cerf, 1980); and John L. -

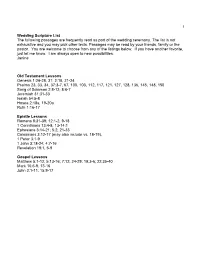

1 Wedding Scripture List the Following Passages Are Frequently Read As

1 Wedding Scripture List The following passages are frequently read as part of the wedding ceremony. The list is not exhaustive and you may pick other texts. Passages may be read by your friends, family or the pastor. You are welcome to choose from any of the listings below. If you have another favorite, just let me know. I am always open to new possibilities. Janine Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31; 2:18, 21-24 Psalms 23, 33, 34, 37:3-7, 67, 100, 103, 112, 117, 121, 127, 128, 136, 145, 148, 150 Song of Solomon 2:8-13; 8:6-7 Jeremiah 31:31-33 Isaiah 54:5-8 Hosea 2:18a, 19-20a Ruth 1:16-17 Epistle Lessons Romans 8:31-39; 12:1-2, 9-18 1 Corinthians 13:4-8, 13-14:1 Ephesians 3:14-21; 5:2, 21-33 Colossians 3:12-17 (may also include vs. 18-19). 1 Peter 3:1-9 1 John 3:18-24; 4:7-16 Revelation 19:1, 5-9 Gospel Lessons Matthew 5:1-12; 5:13-16; 7:12, 24-29; 19:3-6; 22:35-40 Mark 10:6-9, 13-16 John 2:1-11; 15:9-17 2 Old Testament Lessons Genesis 1:26-28, 31 Then God said, "Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth." So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. -

JEWISH PRINCIPLES of CARE for the DYING JEWISH HEALING by RABBI AMY EILBERG (Adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: a Training Manual for Bikur Holim")

A SPECIAL EDITION ON DYING WINTER 2001 The NATIONAL CENTER for JEWISH PRINCIPLES OF CARE FOR THE DYING JEWISH HEALING By RABBI AMY EILBERG (adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: A Training Manual for Bikur Holim") ntering a room or home where death is a gone before and those who stand with us now. Epresence requires a lot of us. It is an intensely We are part of this larger community (a Jewish demanding and evocative situation. It community, a human community) that has known touches our own relationship to death and to life. death and will continue to live after our bodies are It may touch our own personal grief, fears and gone-part of something stronger and larger than vulnerability. It may acutely remind us that we, death. too, will someday die. It may bring us in stark, Appreciation of Everyday Miracles painful confrontation with the face of injustice Quite often, the nearness of death awakens a when a death is untimely or, in our judgement, powerful appreciation of the "miracles that are with preventable. If we are professional caregivers, we us, morning, noon and night" (in the language of may also face feelings of frustration and failure. the Amidah prayer). Appreciation loves company; Here are some Jewish principles of care for the we only need to say "yes" when people express dying which are helpful to keep in mind: these things. B'tselem Elohim (created in the image of the Mterlife Divine) Unfortunately, most Jews have little knowledge This is true no matter what the circumstances at of our tradition's very rich teachings on life after the final stage of life. -

Basic Judaism Course Copr

ה"ב Basic Judaism Course Copr. 2009 Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Syllabus Basic Judaism Course By: Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Greetings and Overview ................................................................................................................. 3 Class Topics.................................................................................................................................... 3 Reccomended Resources ................................................................................................................ 4 Live It, Learn It............................................................................................................................... 6 On Gender Neutrality...................................................................................................................... 7 Adult Bar/Bat Mitzvah.................................................................................................................... 8 Contact Information........................................................................................................................ 8 What is Prayer?............................................................................................................................... 9 Who Is Supposed To Pray?........................................................................................................... 10 Studying Judaism With Honesty and Integrity ............................................................................. 10 Why Are Women and Men Treated Differently in the Synagogue? -

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom an English Translation from the Greek, with Commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St

The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom An English translation from the Greek, with commentary, of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom The annotations in this edition are extracted from two books by Fr. Alexander Schmemann, of blessed memory: 1) The Eucharist published in 1987, and, 2) For The Life of The World, 1963, 1973, both published by Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press. Fr. Schmemann died in 1983 at the age of 62 having been Dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary for the 20 years previously. Any illumination for the reader of the meaning of the Liturgy is directly from Fr. Schmemann’s work; any errors are directly the fault of the extractor. In this edition the quiet prayers of the priest are indicated by being in blue italics, Scripture references are in red, the Liturgical text is in blue, and the commentary is in black. (Traditionally, the service of Orthros is celebrated right before each Liturgy. The traditional end of the Orthros is the Great Doxology. In our church, the end of the Orthros is separated from the Great Doxology by the Studies in the Faith and the Memorials. Thus, it appears that the Great Doxology is the start of The Eucharist, but that is not the case. [ed.]) The Liturgy of the Eucharist is best understood as a journey or procession. It is a journey of the Church into the dimension of the kingdom, the manner of our entrance into the risen life of Christ. It is not an escape from the world, but rather an arrival at a vantage point from which we can see more deeply into the reality of the world. -

Small Project Assistance Program Activities Report 1994

Small Project Assistance Program Activities Report 1994 Office of Training and Program Support Small Project Assistance Program ~ r.~~~ T~D~~~E~ DIRECTOR Dear Colleague: I am pleased to present the 1994 Activity Report for the Small Project Assistance (SPA) Program. For more than a decade, Peace Corps and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) have combined resources to create this unique program which supports community-based, self-help development efforts. In 1994, more than 500 SPA-supported projects were undertaken in over 70 countries around the world. Wherever these projects are being implemented, Peace Corps Volunteers are working with communities to mobilize, organize, and focus resources on grassroots development activities. Through these efforts, SPA grants are being used to complement and help leverage local resources. It is this local resource mobilization that best demonstrates the self-help nature of these initiatives. In addition to the grants provided, more than 50 technical assistance and training activities were supported by SPA in 1994. These activities focused on increasing Volunteer and host country national skills in project design and management. 'Technical assistance funds were also used to support the participation of host country nationals in specific sectoral areas such as environment, health and nutrition, education, food production and women in development. Experience has demonstrated that the skills acquired through these various technical assistance activities are integral to effective project implementation at the community level. Since its inception, the SPA Program has consistently shown that grassroots initiatives have a strong likelihood of success where active community members and interested Peace Corps Volunteers join forces in project design and managment. -

Book of Common Prayer

the book of common prayer and administration of the s a c r a m e n t s with other rites and ceremonies of the church According to the use of the anglican church in north america Together with the new coverdale psalter anno domini 2019 anglican liturgy press the book of common prayer (2019) Copyright © 2019 by the Anglican Church in North America The New Coverdale Psalter Copyright © 2019 by the Anglican Church in North America Published by Anglican Liturgy Press an imprint of Anglican House Media Ministry, Inc. 16332 Wildfire Circle Huntington Beach, CA 92649 Publication of the Book of Common Prayer (2019), including the New Coverdale Psalter, is authorized by the College of Bishops of the Anglican Church in North America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law, and except as indicated below for the incorporation of selections (liturgies) in bulletins or other materials for use in church worship services. First printing, June 2019 Second (corrected) printing, November 2019 Third printing, November 2019 Quotations of Scripture in the Book of Common Prayer (2019) normally follow the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®) except for the Psalms, Canticles, and citations marked with the symbol (T), which indicates traditional prayer book language. The ESV Bible copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. ESV Text Edition: 2016. -

An Analytical Conductor's Guide to the SATB a Capella Works of Arvo Part

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 An Analytical Conductor's Guide to the SATB A Capella Works of Arvo Part Kimberly Anne Cargile University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cargile, Kimberly Anne, "An Analytical Conductor's Guide to the SATB A Capella Works of Arvo Part" (2008). Dissertations. 1106. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1106 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi AN ANALYTICAL CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE TO THE SATB A CAPPELLA WORKS OF ARVO PART by Kimberly Anne Cargile A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY KIMBERLY ANNE CARGILE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi AN ANALYTICAL CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE TO THE SATB A CAPPELLA WORKS OF ARVO PART by Kimberly Anne Cargile Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 DISSERTATION ABSTRACT AN ANALYTICAL CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE TO THE SATB A CAPPELLA WORKS OF ARVO PART by Kimberly Anne Cargile May 2008 Arvo Part (b.