China, Responsibility to Protect, and the Case of Syria from Sovereignty Protection to Pragmatism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of UN Peacekeeping in China's Expanding Strategic Interests

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Marc Lanteigne This Special Report assesses China’s evolving participation in international peacekeeping missions in the context of its rise as a major economic and military power. The report is based on data collection on Chinese foreign and security policy issues as well as fieldwork in China and Norway. Supported by the Asia The Role of UN Center at the United States Institute of Peace, the report is part of USIP’s broader effort to understand China’s engagement in the peace processes and internal conflicts of other nations. Peacekeeping in ABOUT THE AUTHOR Marc Lanteigne is a senior lecturer in security studies in the China’s Expanding Centre for Defence and Security Studies at Massey University in New Zealand. Previously, he was a senior research fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, where he specialized in Chinese and Northeast Asian politics and foreign Strategic Interests policy, as well as Asia-Arctic relations, international political economy, and institution building. He has written on issues related to China’s regional and international relations as well as Summary economic security, the politics of trade, and energy issues. • Despite its growing status in the international system, including in the military sphere, China continues to be a strong supporter of United Nations peacekeeping operations (UNPKO), a stance commonly considered to be more the purview of medium powers. China is also a major contributor of peacekeeping personnel and support. -

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School Head of State: Ashraf Ghani GDP: 664.76 USD per capita Population: 33,895,000 UN Ambassador: Mahmoud Saikal Joined UN: 1946 Current Member of UNSC: No Past UNSC Membership: No Issue 1: Immigration, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers Afghanistan is the highest refugee producing country with roughly six million refugees. Regarding immigration and refugees, Afghanistan believes that all neighboring countries to those with the highest refugee count, such as Syria and Afghanistan, need to have an open door policy to these individuals. The refugees would need to be approved by the government in order to enter and live in the country; however, if denied access they must not be forced back. Refugee camps with adequate food, water, medical help, and shelter must be provided by the UN and its members in order to reduce refugee suffering. Although many of the countries around the world will disagree with this plan, they fail to realize the severity of this issue. In Afghanistan millions of individuals are left to fend for themselves in a foreign land with literally nothing but the clothes on their back. As a country with over six million refugees, we are able understand the necessity for a change in the current situation. The UN distinguishes between asylum seekers and refugees, however those who are not accepted by others need not be excluded from having a proper life. With the dramatic increase of refugees and immigrants around the world resulting from the dramatic increase of wars of crises, the UN must acknowledge and call all people fleeing from their country refugees and not distinguish between the two. -

S/PV.7361 Security Council Provisional Asdf Seventieth Year 7361St Meeting Monday, 19 January 2015, 9.30 A.M

United Nations S/PV.7361 Security Council Provisional asdf Seventieth year 7361st meeting Monday, 19 January 2015, 9.30 a.m. New York President: Ms. Bachelet Jeria/Mr. Barros Melet/Mr. Olguín Cigarroa . .. (Chile) Members: Angola .. Mr. Augusto Chad .......................................... Mr. Cherif China . ......................................... Mr. Liu Jieyi France ......................................... Mr. Lamek Jordan ......................................... Mr. Hmoud Lithuania . ...................................... Ms. Murmokaitė Malaysia ....................................... Mr. Haniff New Zealand .................................... Mr. McLay Nigeria . ........................................ Mr. Laro Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Churkin Spain .......................................... Mr. Ybañez United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ... Sir Mark Lyall Grant United States of America . .......................... Ms. Power Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) ................... Mr. Ramírez Carreño Agenda Maintenance of international peace and security Inclusive development for the maintenance of international peace and security Letter dated 6 January 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Chile to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General (S/2015/6) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 15-01584 (E) *1501584* S/PV.7361 Maintenance of international peace and security 19/01/2015 The meeting was called to order at 9.35 a.m. -

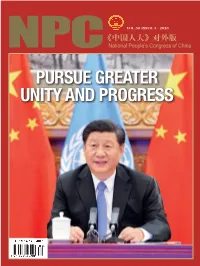

Pursue Greater Unity and Progress News Brief

VOL.50 ISSUE 3 · 2020 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China PURSUE GREATER UNITY AND pROGRESS NEWS BRIEF President Xi Jinping attends a video conference with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres from Beijing on September 23. Liu Weibing 2 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA ISSUE 3 · 2020 3 6 Pursue greater unity and progress Contents UN’s 75th Anniversary CIFTIS: Global Services, Shared Prosperity National Medals and Honorary Titles 6 18 26 Pursue greater unity Global services, shared prosperity President Xi presents medals and progress to COVID-19 fighters 22 9 Shared progress and mutually Special Reports Make the world a better place beneficial cooperation for everyone 24 30 12 Accelerated development of trade in Work together to defeat COVID-19 Xi Jinping meets with UN services benefits the global economy and build a community with a shared Secretary-General António future for mankind Guterres 32 14 Promote peace and development China’s commitment to through parliamentary diplomacy multilateralism illustrated 4 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA 42 The final stretch Accelerated development of trade in 24 services benefits the global economy 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection ISSUE 3 · 2020 Fcous 38 Stop food waste with legislation, 34 crack down on eating shows Top legislature resolves HKSAR Leg- VOL.50 ISSUE 3 September 2020 Co vacancy concern Administrated by General Office of the Standing Poverty Alleviation Committee of National People’s Congress 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection Chief Editor: Wang Yang General Editorial 42 Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, The final stretch Xicheng District, Beijing 37 100805, P.R.China Full implementation wildlife protection Tel: (86-10)5560-4181 law stressed (86-10)6309-8540 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: President Xi Jinping ad- ISSN 1674-3008 dresses a high-level meeting to CN 11-5683/D commemorate the 75th anniversary Price: RMB 35 of the United Nations via video link Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal on September 21. -

September 4, 2019 Hearing Transcript

HEARING ON U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS IN 2019: A YEAR IN REVIEW HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2019 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2019 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN ROBIN CLEVELAND, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: ANDREAS A. BORGEAS KENNETH LEWIS JEFFREY L. FIEDLER MICHAEL A. MCDEVITT HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN HON. JAMES M. TALENT ROY D. KAMPHAUSEN MICHAEL R. WESSEL THEA MEI LEE LARRY M. WORTZEL The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. 110-161 (December 26, 2007) (regarding responsibilities of the Commission, and changing the Annual Report due date from June to December); as amended by the Carl Levin and Howard P. -

The Sino-Russian Partnership and the East Asian Order

Asian Perspective 42 (2018), 355 –386 The Sino-Russian Partnership and the East Asian Order Elizabeth Wishnick After dismissing the Sino-Russian partnership for the past decade, scholars now scramble to assess its significance, particularly with US foreign policy in disarray under the Trump administration. I examine how China and Russia manage their relations in East Asia and the impact of their approach to great power management on the creation of an East Asian order. According to English School theorist Hedley Bull, great power management is one of the ways that order is created. Sino-Russian great power management involves rule making, a distinctive approach to crisis manage - ment, and overlapping policy approaches toward countries such as Burma and the Philippines. I conclude with a comparison between Sino-Russian great power management and the US alliance system, note a few distinctive features of the Trump era, and draw some conclusions for East Asia. KEYWORDS : China, Russia, East Asia, great power, order. AFTER DISMISSING THE SINO -R USSIAN PARTNERSHIP FOR THE PAST decade, scholars now scramble to assess its significance, partic - ularly with US foreign policy in disarray under the Trump admin - istration. Is the Sino-Russian partnership a transactional relation - ship, destined for failure as China rises? Is it an alliance? Is it based on enduring shared norms or less securely premised on transactional interests? Focusing on what partnership is or is not, while interesting as a scholarly exercise, does not, however, advance our understanding of its mechanisms and impact on East Asia. Following the English School and the writings of Hedley Bull, I argue that Russia and China are seeking to create a society of states that defines a pluralist East Asian order. -

Election Portends Continued Tension

CHINA- TAIWAN RELATIONS ELECTION PORTENDS CONTINUED TENSION DAVID G. BROWN, JOHNS HOPKINS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES KYLE CHURCHMAN, JOHNS HOPKINS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES President Tsai Ing-wen triumphed over her populist Kuomintang (KMT) opponent Han Kuo-yu in Taiwan’s January 11, 2020 presidential election, garnering 57.1% of the vote to Han’s 38.6%. Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) also retained its majority in the Legislative Yuan (LY), albeit with the loss of some seats to the KMT and third parties. While there has been considerable attention to Beijing’s influence operations, the election illustrated Beijing’s limited ability to manipulate Taiwan elections. The outcome portends continued deadlock and tension in cross-strait relations in the coming months. Meanwhile, Taipei and Washington have strengthened ties by launching a series of bilateral and multilateral cooperative projects, intended in part to counter both Beijing’s influence operations and its continuing diplomatic, economic, and military pressures on Taiwan. This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 21, No. 3, January 2020. Preferred citation: David G. Brown and Kyle Churchman, “China-Taiwan Relations: Election Portends Continued Tension,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp 69-78. CHINA-TAIWAN RELATIONS | JANUARY 2020 69 Presidential Election Campaign used existing policies to demonstrate sympathy for Hong Kong by accepting fleeing Hong Kong Throughout the fall campaign, Tsai Ing-wen activists seeking temporary residence in Taiwan steadily improved her prospects for winning and welcoming students from disrupted Hong reelection in the January 11, 2020 presidential Kong universities. -

Section 2: the China Model: Return of the Middle Kingdom

SECTION 2: THE CHINA MODEL: RETURN OF THE MIDDLE KINGDOM Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to revise the inter- national order to be more amenable to its own interests and authoritarian governance system. It desires for other countries not only to acquiesce to its prerogatives but also to acknowledge what it perceives as China’s rightful place at the top of a new hierarchical world order. • The CCP’s ambitions for global preeminence have been con- sistent throughout its existence: every CCP leader since Mao Zedong has proclaimed the Party would ultimately prove the superiority of its Marxist-Leninist system over the rest of the world. Under General Secretary of the CCP Xi Jinping, the Chi- nese government has become more aggressive in pursuing its interests and promoting its model internationally. • The CCP aims to establish an international system in which Beijing can freely influence the behavior and access the mar- kets of other countries while constraining the ability of others to influence its behavior or access markets it controls. The “com- munity of common human destiny,” the CCP’s proposed alter- native global governance system, is explicitly based on histor- ical Chinese traditions and presumes Beijing and the illiberal norms and institutions it favors should be the primary forces guiding globalization. • The CCP has attempted to use the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to promote itself as a responsible and benevolent global leader and to prove that its model of governance is su- perior to liberal democracy. Thus far, it appears Beijing has not changed many minds, if any. -

People-Centered Urbanization Program Oct22

Permanent Mission of Italy Permanent Mission of the People’s to the United Nations Republic of China to the United Nations WORLD CITIES DAY 2014 LEADING URBAN TRANSFORMATIONS ECOSOC Chamber – 31 October 2014 (9:30am - 12:30pm) People-centred Urbanisation, Managing Social Inclusion in Today’s Cities Background For the first time in history, in 2008, more than half of the world’s population was recorded to be living in towns and cities. This number is constantly on the rise and is expected to reach almost five billion by 2030 (6.3 billion by 2050). Cities have increasingly become a concentration of peoples with diverse backgrounds, different cultural and ethnic origins and beliefs. The challenges that this new identity and diversity pose for countries and, more broadly, regions are today heightened when concentrated in extremely reduced geographical spaces. Cities of all sizes often struggle to find resources and apply good practices to respond to the magnitude of this change. In fact, cities are faced with the end results of transnational and internal migration1 that further exacerbates challenges already faced by cities in providing equitable access to urban services and infrastructure, including housing, services and employment, and in ensuring adequate planning for the accelerated urban growth. Yet, Local Authorities have little if any say over international and national migration policies and they have little capacity to control migratory flows into their cities. 1 The People’s Republic of China is the biggest country in the world in terms of internal migration, which amounted to 166 million in 2013. See China Science Center of International Eurasian Academy of Sciences/ China Association of Mayors/ Urban Planning Society of China/ UN-Habitat (2014). -

Mr. Liu Jieyi (China) (Spoke in Chinese): the Chinese Delegation Welcomes Spain’S Initiative in Convening This Open Debate

Mr. Liu Jieyi (China) (spoke in Chinese): The Chinese delegation welcomes Spain’s initiative in convening this open debate. We welcome Prime Minister Rajoy Brey to preside over today’s meeting. I wish to thank Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon for his briefing, and the Executive Director of UN-Women, Ms. Mlambo-Ngucka, for hers as well. China has also listened attentively to the briefings by the representatives of civil society. This year coincides with the twentieth anniversary of the holding of the fourth World Conference on Women, and also with the fifteenth anniversary of the Security Council’s adoption of resolution 1325 (2000). On 27 September, China and the United Nations jointly sponsored a global summit on women: the Global Leaders’ Meeting on Gender Equality and Empowerment. The President of China Xi Jinping and representatives from over 140 countries, including more than 80 Heads of State and Government, attended the meeting. The summit was the first of its kind in which commitments on women were made at the State leadership level. It is another milestone of the international cause of women following the Beijing Conference and is of trailblazing significance. The leaders of countries committed to further implement the outcome of the Beijing Conference. That is of great and far- reaching significance for the development of the global cause of women. Resolution 2242 (2015), which was just adopted, also acknowledged the global summit on women. With the efforts of the broad membership, of United Nations bodies and of regional and subregional organizations, the international community in recent years has made progress in implementing resolution 1325 (2000), with major achievements in promoting a greater role for women in peace and security. -

China's Non-Intervention Policy Meets International Military Intervention In

China’s Non-intervention Policy Meets International Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War Era: Focusing on Cases of Illegal Intervention China’s Non-intervention Policy Meets International Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War Era: Focusing on Cases of Illegal Intervention Mu REN ※ Abstract China has long taken the principle of non-intervention as its diplomatic dogma and major rhetorical instrument. However, its non-intervention policy is flexible in facing certain international interventions. This article attempts to explain why the behavior of China’s foreign policy varies in its degree of consistency with the principle of non-intervention by examining China’s attitude and behavior toward different cases of illegal intervention. China’s response to a specific intervention is prudent decision making intertwined with strategic considerations at the international level and with national interests at the domestic level. A theoretical framework based on the IR theory of neo-classical realism is developed to explore the causal mechanism underlying China’s non-intervention policy. Three cases, namely, NATO’s bombing of the FRY regarding Kosovo, the Iraq War, and the Russian intervention in Ukraine over Crimea, are examined to test the arguments. Introduction The principle of non-intervention in the domestic or territorial jurisdiction of other states has been taken as an international norm enshrined in international statements and declarations. However, interventionist activities are hardly uncommon in world politics as intervention is an endemic feature of contemporary international arrangements (Bull, 1986, p.181). Experts have concluded that intervention is the “modern social practice” in the history of international relations (IR).1 Military intervention is the most extreme and most coercive form ※ Doctoral Program in International Relations, Graduate School of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University. -

Nontraditional-Actors-China-Russia

PROTECTING CIVILIANS IN CONFLICT Policy Brief | March 2017 Nontraditional Actors CHINA AND RUSSIA IN AFRICAN PEACE OPERATIONS Elor Nkereuwem IMAGE CREDITS: Front and back cover: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe Page 4: UN Photo/Rick Bajornas Page 10: UN Photo/JC Mcllwaine Page 20: UN Photo/Mark Garten Page 26: UN Photo/Stuart Price © COPYRIGHT 2017 STIMSON CENTER Elor Nkereuwem Contents Executive Summary . 5 List of Abbreviations . 6 Acknowledgments . 8 Introduction . 9 The Peace Agenda . 11 Overview . 11 Setting the Agenda: Security Council Interests and Coalitions . 11 China And Russia In African Peace Operations . 13 Overview of U .N . and A U. Peace Operations in Africa . 13 China’s Support for Peace Operations in Africa . .13 Russia’s Support for Peace Operations in Africa . 16 China and Russia in African Peacekeeping Reforms . 18 African Peace Operations: China and Russia on the Security Council . 21 Actions on the Security Council . 21 Sudan . 22 South Sudan . 25 Burundi . 27 Mali . 28 Libya . .30 China and Russia in African Peace Operations: A Summary . .32 Conclusions . 35 Endnotes . 36 STIMSON | 3 Nontraditional Actors: China and Russia in African Peace Operations 4 | STIMSON Elor Nkereuwem Executive Summary This report seeks to analyze the contributions China and Russia make to peace operations in Africa . Recognizing the role of the United Nations (U N. ). Security Council in setting the agenda for U N. peace operations, the report uses meeting records of U N. resolution deliberations and debates since 1989, as well as interviews with stakeholders, to analyze China’s and Russia’s voting decisions with regard to U .N .