Nontraditional-Actors-China-Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of UN Peacekeeping in China's Expanding Strategic Interests

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Marc Lanteigne This Special Report assesses China’s evolving participation in international peacekeeping missions in the context of its rise as a major economic and military power. The report is based on data collection on Chinese foreign and security policy issues as well as fieldwork in China and Norway. Supported by the Asia The Role of UN Center at the United States Institute of Peace, the report is part of USIP’s broader effort to understand China’s engagement in the peace processes and internal conflicts of other nations. Peacekeeping in ABOUT THE AUTHOR Marc Lanteigne is a senior lecturer in security studies in the China’s Expanding Centre for Defence and Security Studies at Massey University in New Zealand. Previously, he was a senior research fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, where he specialized in Chinese and Northeast Asian politics and foreign Strategic Interests policy, as well as Asia-Arctic relations, international political economy, and institution building. He has written on issues related to China’s regional and international relations as well as Summary economic security, the politics of trade, and energy issues. • Despite its growing status in the international system, including in the military sphere, China continues to be a strong supporter of United Nations peacekeeping operations (UNPKO), a stance commonly considered to be more the purview of medium powers. China is also a major contributor of peacekeeping personnel and support. -

Russia's Hybrid Warfare

Research Paper Research Division – NATO Defense College, Rome – No. 105 – November 2014 Russia’s Hybrid Warfare Waging War below the Radar of Traditional Collective Defence by H. Reisinger and A. Golts1 “You can’t modernize a large country with a small war” Karl Schlögel The Research Division (RD) of the NATO De- fense College provides NATO’s senior leaders with “Ukraine is not even a state!” Putin reportedly advised former US President sound and timely analyses and recommendations on current issues of particular concern for the Al- George W. Bush during the 2008 NATO Summit in Bucharest. In 2014 this liance. Papers produced by the Research Division perception became reality. Russian behaviour during the current Ukraine convey NATO’s positions to the wider audience of the international strategic community and con- crisis was based on the traditional Russian idea of a “sphere of influence” and tribute to strengthening the Transatlantic Link. a special responsibility or, stated more bluntly, the “right to interfere” with The RD’s civil and military researchers come from countries in its “near abroad”. This perspective is also implied by the equally a variety of disciplines and interests covering a 2 broad spectrum of security-related issues. They misleading term “post-Soviet space.” The successor states of the Soviet conduct research on topics which are of interest to Union are sovereign countries that have developed differently and therefore the political and military decision-making bodies of the Alliance and its member states. no longer have much in common. Some of them are members of the European Union and NATO, while others are desperately trying to achieve The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the this goal. -

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School

Afghanistan Anam Ahmed | Elizabethtown High School Head of State: Ashraf Ghani GDP: 664.76 USD per capita Population: 33,895,000 UN Ambassador: Mahmoud Saikal Joined UN: 1946 Current Member of UNSC: No Past UNSC Membership: No Issue 1: Immigration, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers Afghanistan is the highest refugee producing country with roughly six million refugees. Regarding immigration and refugees, Afghanistan believes that all neighboring countries to those with the highest refugee count, such as Syria and Afghanistan, need to have an open door policy to these individuals. The refugees would need to be approved by the government in order to enter and live in the country; however, if denied access they must not be forced back. Refugee camps with adequate food, water, medical help, and shelter must be provided by the UN and its members in order to reduce refugee suffering. Although many of the countries around the world will disagree with this plan, they fail to realize the severity of this issue. In Afghanistan millions of individuals are left to fend for themselves in a foreign land with literally nothing but the clothes on their back. As a country with over six million refugees, we are able understand the necessity for a change in the current situation. The UN distinguishes between asylum seekers and refugees, however those who are not accepted by others need not be excluded from having a proper life. With the dramatic increase of refugees and immigrants around the world resulting from the dramatic increase of wars of crises, the UN must acknowledge and call all people fleeing from their country refugees and not distinguish between the two. -

S/PV.7361 Security Council Provisional Asdf Seventieth Year 7361St Meeting Monday, 19 January 2015, 9.30 A.M

United Nations S/PV.7361 Security Council Provisional asdf Seventieth year 7361st meeting Monday, 19 January 2015, 9.30 a.m. New York President: Ms. Bachelet Jeria/Mr. Barros Melet/Mr. Olguín Cigarroa . .. (Chile) Members: Angola .. Mr. Augusto Chad .......................................... Mr. Cherif China . ......................................... Mr. Liu Jieyi France ......................................... Mr. Lamek Jordan ......................................... Mr. Hmoud Lithuania . ...................................... Ms. Murmokaitė Malaysia ....................................... Mr. Haniff New Zealand .................................... Mr. McLay Nigeria . ........................................ Mr. Laro Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Churkin Spain .......................................... Mr. Ybañez United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland ... Sir Mark Lyall Grant United States of America . .......................... Ms. Power Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) ................... Mr. Ramírez Carreño Agenda Maintenance of international peace and security Inclusive development for the maintenance of international peace and security Letter dated 6 January 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Chile to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General (S/2015/6) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 15-01584 (E) *1501584* S/PV.7361 Maintenance of international peace and security 19/01/2015 The meeting was called to order at 9.35 a.m. -

S/PV.7886 Maintenance of International Peace and Security 21/02/2017

United Nations S/ PV.7886 Security Council Provisional Seventy-second year 7886th meeting Tuesday, 21 February 2017, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Klimkin/Mr. Yelchenko ....................... (Ukraine) Members: Bolivia (Plurinational State of) ..................... Mr. Arancibia Fernández China ......................................... Mr. Liu Jieyi Egypt ......................................... Mr. Aboulatta Ethiopia ....................................... Mr. Alemu France ........................................ Mr. Delattre Italy .......................................... Mr. Cardi Japan ......................................... Mr. Bessho Kazakhstan .................................... Mr. Vassilenko Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Iliichev Senegal ....................................... Mr. Seck Sweden ....................................... Ms. Söder United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Rycroft United States of America .......................... Mrs. Haley Uruguay ....................................... Mr. Rosselli Agenda Maintenance of international peace and security Conflicts in Europe Letter dated 3 February 2017 from the Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General (S/2017/108) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original -

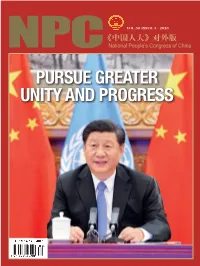

Pursue Greater Unity and Progress News Brief

VOL.50 ISSUE 3 · 2020 《中国人大》对外版 NPC National People’s Congress of China PURSUE GREATER UNITY AND pROGRESS NEWS BRIEF President Xi Jinping attends a video conference with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres from Beijing on September 23. Liu Weibing 2 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA ISSUE 3 · 2020 3 6 Pursue greater unity and progress Contents UN’s 75th Anniversary CIFTIS: Global Services, Shared Prosperity National Medals and Honorary Titles 6 18 26 Pursue greater unity Global services, shared prosperity President Xi presents medals and progress to COVID-19 fighters 22 9 Shared progress and mutually Special Reports Make the world a better place beneficial cooperation for everyone 24 30 12 Accelerated development of trade in Work together to defeat COVID-19 Xi Jinping meets with UN services benefits the global economy and build a community with a shared Secretary-General António future for mankind Guterres 32 14 Promote peace and development China’s commitment to through parliamentary diplomacy multilateralism illustrated 4 NATIONAL PEOPle’s CoNGRESS OF CHINA 42 The final stretch Accelerated development of trade in 24 services benefits the global economy 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection ISSUE 3 · 2020 Fcous 38 Stop food waste with legislation, 34 crack down on eating shows Top legislature resolves HKSAR Leg- VOL.50 ISSUE 3 September 2020 Co vacancy concern Administrated by General Office of the Standing Poverty Alleviation Committee of National People’s Congress 36 Top legislator stresses soil protection Chief Editor: Wang Yang General Editorial 42 Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang, The final stretch Xicheng District, Beijing 37 100805, P.R.China Full implementation wildlife protection Tel: (86-10)5560-4181 law stressed (86-10)6309-8540 E-mail: [email protected] COVER: President Xi Jinping ad- ISSN 1674-3008 dresses a high-level meeting to CN 11-5683/D commemorate the 75th anniversary Price: RMB 35 of the United Nations via video link Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal on September 21. -

September 4, 2019 Hearing Transcript

HEARING ON U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS IN 2019: A YEAR IN REVIEW HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2019 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2019 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN ROBIN CLEVELAND, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: ANDREAS A. BORGEAS KENNETH LEWIS JEFFREY L. FIEDLER MICHAEL A. MCDEVITT HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN HON. JAMES M. TALENT ROY D. KAMPHAUSEN MICHAEL R. WESSEL THEA MEI LEE LARRY M. WORTZEL The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. 110-161 (December 26, 2007) (regarding responsibilities of the Commission, and changing the Annual Report due date from June to December); as amended by the Carl Levin and Howard P. -

General Assembly Official Records Seventy-First Session

United Nations A/71/ PV.72 General Assembly Official Records Seventy-first session 72nd plenary meeting Tuesday, 21 March 2017, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Thomson ......................................... (Fiji) The meeting was called to order at 10.15 a.m. the theatre of diplomacy, Ambassador Churkin was a giant, a deep and eloquent intellectual with a sharp wit Tribute to the memory of His Excellency and a disarmingly approachable manner. He served his Ambassador Vitaly Churkin, Permanent country with passion and pride. As the Ambassador of Representative of the Russian Federation to the the Russian Federation to the United Nations for more United Nations than a decade, he became the longest-serving member The President: Before we proceed to the item of the Security Council. Ambassador Churkin’s quick on our agenda, it is my sad duty to pay tribute to intelligence was admired by all, his grasp of the the memory of the late Permanent Representative intricacies of international political affairs undisputed. of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, His His mastery of negotiation and due process commanded Excellency Ambassador Vitaly Churkin, who passed respect from all quarters. But it is the passing of the away on Monday, 20 February 2017. I am joined for man himself that we mourn — the loss of his dry wit, the tribute this morning by members of his bereaved his knowing looks, eye to eye, his smiling dismissal of family, Mrs. Irina Churkin, wife of the late Ambassador, and Mr. Maksim Churkin, their son. On behalf of the nonsense, and his wide cultural reach into literature, General Assembly, I would like to extend to them our theatre and film. -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

Russian Strategic Narratives on R2P in the 'Near Abroadr

Nationalities Papers (2020), 1–19 doi:10.1017/nps.2020.54 ARTICLE Russian Strategic Narratives on R2P in the ‘Near Abroad’ Juris Pupcenoks1* and Eric James Seltzer2 1Department of Political Science, Marist College, Poughkeepsie, New York, USA and 2School of Law, St. John’s University, Queens, New York, USA *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Abstract This article assesses Russian strategic narratives towards its interventions in Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014–16) based on a new database of 50 statements posted on the websites of the Russian Mission to the United Nations and the President of Russia homepage. By looking more broadly at Russian strategic narratives aimed at persuading other global actors and publics abroad and at home, this article identifies how Russia attempted to develop a story that could win global acceptance. This analysis shows that contrary to traditional Russian emphasis on sovereign responsibility and non-intervention, Russia supported claims for self-determination by separatist groups in Georgia and Ukraine. Russia used deception and disinformation in its strategic narratives as it mis-characterized these conflicts using Responsibility to Protect (R2P) language, yet mostly justified its own interventions through references to other sources of international law. Russian strategic narratives focused on delegitimizing the perceived opponents, making the case for the appropriateness of its own actions, and projecting what it proposed as the proper solution to the conflicts. It largely avoided making any references to its own involvement in the Donbas at all. Additionally, Russia’s focus on the protection of co-ethnics and Russian-speakers is reminiscent of interventions in the pre- R2P era. -

The Sino-Russian Partnership and the East Asian Order

Asian Perspective 42 (2018), 355 –386 The Sino-Russian Partnership and the East Asian Order Elizabeth Wishnick After dismissing the Sino-Russian partnership for the past decade, scholars now scramble to assess its significance, particularly with US foreign policy in disarray under the Trump administration. I examine how China and Russia manage their relations in East Asia and the impact of their approach to great power management on the creation of an East Asian order. According to English School theorist Hedley Bull, great power management is one of the ways that order is created. Sino-Russian great power management involves rule making, a distinctive approach to crisis manage - ment, and overlapping policy approaches toward countries such as Burma and the Philippines. I conclude with a comparison between Sino-Russian great power management and the US alliance system, note a few distinctive features of the Trump era, and draw some conclusions for East Asia. KEYWORDS : China, Russia, East Asia, great power, order. AFTER DISMISSING THE SINO -R USSIAN PARTNERSHIP FOR THE PAST decade, scholars now scramble to assess its significance, partic - ularly with US foreign policy in disarray under the Trump admin - istration. Is the Sino-Russian partnership a transactional relation - ship, destined for failure as China rises? Is it an alliance? Is it based on enduring shared norms or less securely premised on transactional interests? Focusing on what partnership is or is not, while interesting as a scholarly exercise, does not, however, advance our understanding of its mechanisms and impact on East Asia. Following the English School and the writings of Hedley Bull, I argue that Russia and China are seeking to create a society of states that defines a pluralist East Asian order. -

Election Portends Continued Tension

CHINA- TAIWAN RELATIONS ELECTION PORTENDS CONTINUED TENSION DAVID G. BROWN, JOHNS HOPKINS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES KYLE CHURCHMAN, JOHNS HOPKINS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES President Tsai Ing-wen triumphed over her populist Kuomintang (KMT) opponent Han Kuo-yu in Taiwan’s January 11, 2020 presidential election, garnering 57.1% of the vote to Han’s 38.6%. Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) also retained its majority in the Legislative Yuan (LY), albeit with the loss of some seats to the KMT and third parties. While there has been considerable attention to Beijing’s influence operations, the election illustrated Beijing’s limited ability to manipulate Taiwan elections. The outcome portends continued deadlock and tension in cross-strait relations in the coming months. Meanwhile, Taipei and Washington have strengthened ties by launching a series of bilateral and multilateral cooperative projects, intended in part to counter both Beijing’s influence operations and its continuing diplomatic, economic, and military pressures on Taiwan. This article is extracted from Comparative Connections: A Triannual E-Journal of Bilateral Relations in the Indo-Pacific, Vol. 21, No. 3, January 2020. Preferred citation: David G. Brown and Kyle Churchman, “China-Taiwan Relations: Election Portends Continued Tension,” Comparative Connections, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp 69-78. CHINA-TAIWAN RELATIONS | JANUARY 2020 69 Presidential Election Campaign used existing policies to demonstrate sympathy for Hong Kong by accepting fleeing Hong Kong Throughout the fall campaign, Tsai Ing-wen activists seeking temporary residence in Taiwan steadily improved her prospects for winning and welcoming students from disrupted Hong reelection in the January 11, 2020 presidential Kong universities.