The Liberalization Process of Satire in Postauthoritarian Democracies: Potentials and Limits in Mexico’S Network Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

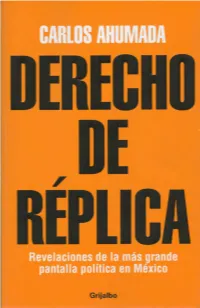

Carlos Ahumada Kurtz

Cnrlo8 Ahumada Kurtz nació en - 1963, en Argentina; es mexicano por naturalizaci6n. Hlzo estudios en el Colegio de Ciencias y Humanidades y en la Facultad de Ciencias de la uw. En 1983 obtuvo el Premio Nacional de la Juventud. Su Ércüvidad empresarial se ha desplegado en diversos campos: agricultura, minerfa, industria restaurantera, futbol profesional, construcci6n, entre otros. En 2003 fundd el peiidico El Independiente. Actualmente radica en Argentina Derecho de réplica es su primer libro. DERECHO DE RÉPLICA Revelaciones de la más grande pantalla política en México CARLOS AHUMADA KURTZ DERECHO DE RÉPLICA Revelaciones de la más grande pantalla política en México Grijalbo Derecho de riplica Revelaciones de la más grande pantalla poI/tica en México Primera edición: abril, 2009 Primera reimpresión: abril, 2009 D. R. (:)2009, Carlos Ahumada Kurtz D. R O 2009, derechos de edición mundiales en lengua castellana: Random House Mondadori, S.A. de C.v. Av. Hornero núm. 544, col. Cbapultepec Morales, Delegación Miguel Hidalgo, 11570, México, DF www.rhmx.com.mx Comentarios sobre la edición y el contenido de este libro a: [email protected] Queda rigurosamente prohibida, sin autorización escrita de los titu- lares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas por las leyes, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o pro- . cedimiento, comprendidos la reprografla, el tratamiento informático, asi como la distribución de ejemplares de la misma mediante alquiler o préstamo públicos. ISBN 978~607-429-437-8 Impreso en México / Printed in Mexico Dedico este libro a quienes más me inspiraron y motivaron a escribirlo. Con ellos tengo una deuda de gratitud eterna. -

CAPÍTULO 4 RESULTADOS 4.1 Descripción Del Trabajo De Campo

CAPÍTULO 4 RESULTADOS 4.1 Descripción del trabajo de campo El trabajo de campo realizado para efectuar el análisis de recepción del programa El Privilegio de mandar se llevó a cabo en un periodo que comprende desde el 11 de julio hasta el 27 de septiembre de 2006. A pesar de que en un principio se había considerado que el trabajo de campo se realizaría antes del 9 de julio, fecha en la que se transmitió el último capítulo del programa, esta extensión de tiempo resultó favorable debido a la polémica surgida sobre la emisión final de El Privilegio de mandar. Dicho capítulo fue mencionado por los informantes durante los grupos focales así como en las entrevistas a profundidad y generó opiniones las cuales son de gran utilidad para analizar tanto la percepción del programa como la recepción de los mensajes emitidos por El Privilegio de mandar según la postura política de los informantes. La extensión del tiempo del trabajo de campo se dio sin intención alguna. Más que nada, fue el resultado de la dificultad de encontrar informantes con las características requeridas para esta investigación. El Privilegio de mandar: Análisis de la recepción de la comedia política mexicana 117 Resultados Aunque las informantes son residentes de la ciudad de Puebla, la investigación etnográfica fue realizada tanto en Cholula como en Puebla, según las peticiones de los informantes así como su localización ya que se buscaba un lugar que les acomodara a los participantes de los grupos. Los grupos focales se realizaron en lugares públicos, en cafeterías para ser más preciso el dato. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Espacio Abierto ISSN: 1315-0006 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Fernández Poncela, Anna María El humor en las elecciones o las elecciones del humor Espacio Abierto, vol. 29, núm. 2, 2020, -Junio, pp. 205-237 Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12264379011 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Volumen 29 Nº 2 (Abril - Junio 2020): 205- 236 El humor en las elecciones o las elecciones del humor. Anna María Fernández Poncela. Resumen. El objetivo de este texto es un análisis del humor en el proceso elec- toral presidencial de México, 2018. Se centra en las teorías, tipos y funciones del humor en general, aplicadas de manera particular en este estudio de caso. Esto se hace a través de la revisión de memes, caricaturas, chistes, videos, canciones y bromas que circularon en los discursos políticos, los medios de comunicación y las redes sociales digitales. Como resultado decir que predominó un humor hostil, de defensa o de ataque. Palabras clave: elecciones, humor, chistes, memes, candidatos, México. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Xochimilco. Coyoacán DF, Méxic0. E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Recibido: 17/12/2019 - Aceptado: 21/02/2020 El humor en las elecciones o las elecciones del humor. Anna María Fernández Poncela. /206 The humor in the elections or the elections of humor. -

Noticias Legislativas

NOTICIAS LEGISLATIVAS Dirección General de Información Legislativa 3 de mayo de 2018 I. CONTEXTO Poder Ejecutivo El Presidente Enrique Peña Nieto destacó que el Infonavit ha sido piedra angular de la creación de patrimonio y la conformación de ciudades en México. Abundó que el organismo se ha convertido en la principal institución hipotecaria de América Latina y la cuarta más grande e importante el mundo. Afirmó que en la actual administración se han otorgado tres millones de créditos, prácticamente uno de cada tres, cantidad mayor a la de cualquier otro sexenio. El Primer Mandatario encabezó la Cumbre de Financiamiento a la Vivienda. Para hoy tiene programado asistir a la 59 Semana Nacional de Radio y Televisión en la Expo Santa Fe. (Noticias MVS) II. QUEHACER LEGISLATIVO 1.- Debate en la Cámara de Diputados Temas de interés - Jesús Rafael Méndez Salas (Panal), integrante de la Comisión de Juventud, urgió a las autoridades a que impartan talleres y programas de educación sexual integral, a fin de evitar embarazos no deseados y la propagación de Enfermedades de Transmisión Sexual (ETS) en los adolescentes. Sostuvo que “en 2016, México registró la tasa más alta de madres adolescentes de entre los 35 países que integran la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos (OCDE), ya que uno de cada 15 alumbramientos fue de mujeres de entre 15 y 19 años de edad”. (Cámara de Diputados) - Juan Alberto Blanco Zaldívar (PAN) señaló la necesidad de que el Sistema de Aguas de la Ciudad de México (Sacmex) diseñe e impulse un programa de abasto de agua para la capital, a fin de evitar especulaciones y un posible lucro indebido. -

Semblanza “Acerca” Detrás De Las Grandes Producciones Nacionales

Semblanza “Acerca” etrás de las grandes producciones nacionales que D Carla ha sabido compenetrar su carrera con la tiene Televisa, existen talentos que han posicionado a cimentación de una familia, también es compañera nivel internacional las telenovelas mexicanas. de vida, amiga y madre siendo un gran ejemplo para todas las mujeres que se enorgullecen al Ella es Carla Estrada. tener satisfacciones profesionales y realizaciones personales. Ella es pilar elemental en el éxito de todos Carla nació en México es hija de una talentosa sus productos y definitivamente una pieza importante actriz y un decano del periodismo por lo que su en su núcleo familiar. relación con el medio artístico lo lleva en la sangre y creció rodeada de grandes personalidades, es La lista de reconocimientos y premios que tiene Carla licenciada en comunicación egresada de la Universidad Estrada es interminable, siendo el más importante Metropolitana, empezó su carrera en Televisa en el el reconocimiento del público y el de la gente que área administrativa y muy pronto incursionó en la trabaja con ella no sin mencionar que catedráticos, producción siendo la primer mujer directora de mercadólogos, instituciones y expertos en el medio cámaras y de escena, iniciándose en los exteriores de las comunicaciones valoran su trabajo tanto a de la telenovela “Vanessa” y en 1986 fue productora nivel nacional como internacional. ejecutiva del programa de concursos y musical XETU. Carla sin duda es reconocida pero también sabe reconocer, por lo que ha logrado mantener desde hace Desde entonces Carla Estrada no ha dejado de crear más de 20 años un equipo de trabajo fiel, profesional brindándole tanto al público mexicano como extrajero y sólido; hablar de Carla Estrada es hablar de una grandes producciones de calidad, tanto en programas institución en la producción del entretenimiento, pero unitarios como telenovelas haciendo evidente su también es hablar de calidad como ser humano como gran profesionalismo, entrega, pasión y amor por lo profesional y como empresaria. -

Los Empresarios Mexicanos Durante El Gobierno De Peña Nieto1

Foro internacional ISSN: 0185-013X ISSN: 2448‐6523 El Colegio de México Los empresarios mexicanos durante el gobierno de Peña Nieto1 Alba Vega, Carlos 1 Los empresarios mexicanos durante el gobierno de Peña Nieto Foro internacional, vol. LX, núm. 2, 2020 El Colegio de México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59963277007 DOI: 10.24201/fi.v60i2.2733 PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Artículos Los empresarios mexicanos durante el gobierno de Peña Nieto1 Mexican business leaders during the Peña Nieto administration Les hommes d’affaires mexicains sous le gouvernement de Peña Nieto Carlos Alba Vega [email protected] Colegio de México, Mexico Resumen: Con base en el examen de hechos cruciales tanto del ámbito económico como electoral, se estudian las relaciones entre el sector empresarial y el Estado mexicano durante el gobierno del presidente Enrique Peña Nieto. Tras un análisis histórico que llega a la actualidad, se profundiza en la relación de los empresarios con los gobiernos Foro internacional, vol. LX, núm. 2, 2020 del PAN, lo cual a su vez se relaciona directamente con la transición a la democracia en México en el año 2000. El centro del análisis es la relación de los empresarios con el El Colegio de México gobierno de Peña Nieto a partir de las reformas más importantes para los empresarios: Recepción: 01 Junio 2019 la fiscal y la energética, sin soslayar la laboral y la educativa. Al final del texto se presenta Aprobación: 01 Noviembre 2019 una caracterización de la relación de los empresarios con Andrés Manuel López Obrador DOI: 10.24201/fi.v60i2.2733 como candidato y como presidente en su primer año de gobierno. -

Bañuelosorozco Tesisdemaestri

DISTANCIAMIENTO CRITICO Y NEGOCIACIÓN TELEVISIVA EN EL PROCESO DE SOCIALIZACIÓN POLÍTICA DE LOS NIÑOS DE SALTILLO Y MONTERREY TECNOLÓGICO DE MONTERREY TESIS MAESTRÍA EN CIENCIAS EN COMUNICACIÓN INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY CAMPUS MONTERREY POR BERENICE HAYDEE BAÑUELOS OROZCO MAYO DE 2007 DISTANCIAMIENTO CRÍTICO Y NEGOCIACIÓN TELEVISIVA EN EL PROCESO DE SOCIALIZACIÓN POLÍTICA DE LOS NIÑOS DE SALTILLO Y MONTERREY TECNOLÓGICO DE MONTERREY TESIS MAESTRÍA EN CIENCIAS EN COMUNICACIÓN INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY CAMPUS MONTERREY POR BERENICE HAYDEÉ BAÑUELOS OROZCO MAYO DE 2007 DISTANCIAMIENTO CRÍTICO Y NEGOCIACIÓN TELEVISIVA EN EL PROCESO DE SOCIALIZACIÓN POLÍTICA DE LOS NIÑOS DE SALTILLO Y MONTERREY POR BERENICE HAYDEÉ BAÑUELOS OROZCO TESIS PRESENTADA A LA DIVISIÓN DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESTE TRABAJO ES REQUISITO PARCIAL PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE MAESTRA EN CIENCIAS EN COMUNICACIÓN INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO Y DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY MAYO DE 2007 Al Amor pleno Que se manifiesta en el amor sin medida de mis padres, Creadores, modeladores y libertadores de mi ser. A Ti, por amarme desde antes de nacer... A mis padres, Maru e Isaías, por su amor, el respeto a mis decisiones y el apoyo incondicional para lograr mis sueños... A París, Isa y Tony, por vincularme con mi origen, por como son y se dan, y por permitir que los quiera tan melosamente... A José Carlos, por creer en mí, darme la oportunidad de crecer en el campo de la investigación... y por ser mi amigo... A Ornar Hernández, por defender tus ideas y tu identidad. Por apostarle al amor.. -

Copyright by Maria De Los Ángeles Flores Gutiérrez 2008

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UT Digital Repository Copyright by Maria de los Ángeles Flores Gutiérrez 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Maria de los Ángeles Flores Gutiérrez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Who Sets the Media Agenda? News vs. Advertising Committee: Maxwell E. McCombs, Supervisor Dominic Lasorsa Chappell Lawson Paula Poindexter Joseph Straubhaar Who Sets the Media Agenda? News vs. Advertising by María de los Ángeles Flores Gutiérrez, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2008 Dedication In the memory of my grandmother Doña Margarita Talamás Vázquez de Gutiérrez Treviño (1918-2008) Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude and appreciation to my advisor, Maxwell E. McCombs, for his mentorship and encouragement throughout the process of this dissertation. Additionally, I want to thank my dissertation committee members—Dominic Lasorsa, Chappell Lawson, Paula Poindexter, and Joseph Straubhaar—for their advice and assistance. I extend my gratitude to Carol Adams Means for assisting me closely, especially in reviewing early versions of this research, and Dr. Herbert M. Levine for editing my dissertation. My appreciation is also extended to the Center of Communication Research at Monterrey Tech (CINCO) director José Carlos Lozano and his graduate students: Citlalli Sánchez Hernández, Esmeralda González Coronado, Eduardo García Reyes, Andrea Menchaca Trillo, and Paola Gabriela López Arnaut for their assistance with the coding conducted for this research. -

Trump Demanda Frenar

Arriola plantea “El privilegio de mandar” se queda militares para XQÀQGHVHPDQDPiVHQOD&'0;IXQFLRQHV atacar venta el 6 y 8 de abril en el Centro Cultural Teatro 1 >31 de drogas >5 $10$ PESOS Martes 3 de abril de 2018 DIARIOIMAGEN AñoA XII No. 3338 México [email protected] / [email protected] Embate de Trump +LÄULUHNLUKHSVZ Peña pide WYPUJPWHSLZJHUKPKH[VZ respeto en WYLZPKLUJPHSLZ negociación Ya en la contienda presidencial real, las encuestas siguen colocando a Andrés Manuel del TLCAN López Obrador muy adelante de Ricardo Anaya `KL1VZt(U[VUPV4LHKL*VUÄHKVKL\U[YP\UMV Luego de las exigencias inexistente, el tabasqueño optó por pelear con y advertencias de Donald Donald Trump. Mientras tanto, Anaya Cortés, dio Trump sobre el TLCAN, el HJVUVJLYJPUJVLQLZWHYH[YHUZMVYTHYHSWHxZ! presidente Enri- 9tNPTLUWVSx[PJV/VULZ[PKHK(KP}ZHSTPLKV que Peña Nieto Crecimiento económico e igualdad (nadie se demandó... >14 queda atrás) y México en el mundo. Por su parte, Meade Kuribreña emplazó a sus contrincantes a elegir tiempo, lugar y circunstancia para debatir El dato sobre su situación inmobiliaria y En el primer bimestre patrimonial. de 2018, las remesas >3 y 4 enviadas a México por connacionales sumaron 4 mil 415 mdd, monto histórico para un mismo periodo, con Podrá pagarse sin recargos hasta el 31 de mayo incremento de 7.2% respecto al año pasado, según Banxico >12 HOY ESCRIBEN (TWSxH,KVTL_TLZLZ Roberto Vizcaíno >9 Ramón Zurita >7 Víctor Sánchez Baños >13 Francisco Rodríguez >15 WSHaVKL[LULUJPH]LOPJ\SHY José A. López Sosa >17 Salvador Sánchez >14 Al 20 de marzo, sólo un millón 177 mil 813 contribuyentes Guillermina Gómora >12 habían cumplido; el padrón es de 7.8 millones de unidades Augusto Corro >8 Por José Luis Montañez o Usos de Vehículos, mismo a este subsidio. -

El Cambio De Preferencias Electorales Durante La Campaña Para La Elección De Presidente De La República En El Proceso Electoral De 2006 En México

Este libro forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx CAPÍTULO IV El cambio de preferencias electorales durante la campaña para la elección de Presidente de la República en el proceso electoral de 2006 en México La otredad estaba del lado de lo no ortodoxo, lo ajeno, lo extraño, en cambio en el otro extremo estaba lo conocido, la certeza y la certidumbre de lo “correcto y explorado”. Germán Pérez Fernández257 INTRODUCCIÓN Una vez que en los capítulos anteriores hemos analizado el mo- delo de la Teoría Amplia de la Racionalidad y los elementos teóricos y metodológicos que le asociaremos para llevar a cabo el estudio del cambio racional de preferencias electorales durante el pro- ceso electoral de 2006 en México, a continuación revisaremos cuáles fueron los actores políticos que participaron en el proceso, las instituciones políticas que tuvieron injerencia, los spots que se transmitieron y la forma en que se desarrolló el proceso mismo. En el capítulo se hace referencia a las formas y procesos que uti- lizaron los partidos para elegir a sus candidatos a la presidencia, 257 Pérez Fernández, Germán, “La campaña indeseable”, en: Peschard, Jacqueline (comp.) 2 de julio: reflexiones y alternativas. FCPyS-UNAM. México, 2006, p. 287. 138 GRUPO PARLAMENTARIO DEL PRD. LXI LEGISLATURA. CÁMARA DE DIPUTADOS Este libro forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx el porcentaje de electores volátiles que decidieron su voto a partir de la información que recibieron de los spots en televisión, la in- tervención de los poderes fácticos y la forma de clasificación de los spots. -

Complejo Del Espectáculo Político Integral. Orígenes De La Movilización Mediático-Electoral De Masas

VERSIÓN ESTUDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN Y POLÍTICA - NUEVA ÉPOCA http://version.xoc.uam.mx ISSN 2007-5758 Complejo del espectáculo político integral. Orígenes de la movilización mediático-electoral de masas. Caso elecciones 2006 Pablo Gaytán Santiago* El presente artículo, Complejo del espectáculo político integral. Orígenes de la movi- lización mediático-electoral de masas. Caso elecciones 2006, explora los comienzos del marketing político en las elecciones presidenciales mexicanas, el discurso me- diático de la “guerra sucia” electoral, el papel político y la movilización emocional promovida por los medios de comunicación electrónicos (televisión) en el proceso electoral de 2006, así como los comportamientos mediáticos y nihilistas de la clase política partidista, capaz de desmoronar todo valor social y político. A lo largo del escrito introduzco una serie de referencias audio-visuales difundidas en Internet y algunas de mi autoría, las cuales pueden vincularse para obtener una visión múltiple del artículo que les presento a continuación. Palabras clave: democracia, clase política, espectáculo político, guerra mediática, movilización mediática. In this article called, “The Complex Politic Integral Spectacle. Media-election and mass mobilization in México 2006”, I explore the historical origin of political mar- keting of the Mexican president elections, the “dirty war” of media speech, the politic role and emotional mobilization cause by electronic media communication (television) in the electoral process of 2006, also the media behavior of the nihilist political party, who is able to fall to pieces each social and political value. Through this paper I introduce a couple of audio-visual references who are spread by Internet and some other of my own production. -

Chairo:Una Estrategia Propagand

ARTÍCULOS Chairo: Una estrategia propagand estrategia Una Chairo: Chairo: Una estrategia propagandística fallida del Estado Chairo: A failed propagandistic strategy of the State í stica fallida del Estado del fallida stica · Luís Fernando Bolaños y María Gabriela López Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas, México Fecha de recepción: 6 de abril de 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15304/ricd.3.10.5961 Fecha de aprobación: 1 de julio de 2019 NOTAS BIOGRÁFICAS Luís Fernando Bolaños es doctor en Ciencias Sociales y Humanísticas por el Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) de la Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. Trabaja en temas relacionados con la diversidad cultural, contraculturas, identidades y cultura de masas. Contacto: [email protected] María Gabriela López es doctora en Estudios Regionales por la Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas y doctora en Dirección y Planificación del Turismo por la Universidad de Alicante. Es profesora e investigadora en la licenciatura en Comunicación Intercultural de la Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas. Contacto: [email protected] Resumen Este artículo analiza la construcción del término chairo y su uso propagandístico en las elecciones presidenciales de 2018 en México, donde las redes sociales se constituyeron como los principales medios para ridiculizar y desprestigiar a los seguidores de Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). El texto presenta algunos antecedentes de este término, identifica los estereotipos otorgados a los simpatizantes del pensamiento de izquierda en dicho contexto, los discursos generados alrededor de ellos, el uso de los memes y la nada sutil estrategia de Estado para intentar legitimar un sistema político en decadencia.