The Role (S) of the Intellectual in the Films of Godard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

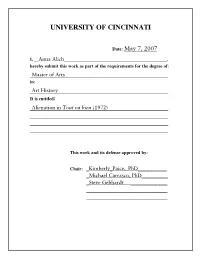

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

'To Realise the Ideal': Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard's Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)

‘To Realise the Ideal’: Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard’s Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve qui peut (la vie) •Richard Morris Made in 1979, Jean-Luc Godard’s Sauve qui peut photocopied images of the film’s three principal (la vie) occupies a uniquely pivotal position in the actors, Jacques Dutronc, Isabelle Huppert and director’s career, representing as it does the Miou-miou (replaced in the completed film by closing, culminatory opus of one decade and the Natalie Baye). These images rise up through the inaugural work of another. It is not, however, my machine as the paper feeds through it whilst the intention to address the specified film in a direct print head moves back and forth typing the way. I shall instead be talking around it, so to film’s title over the images. Meanwhile, Godard speak, with a view to exploring something of comments offscreen upon these two axes of how Godard actually conceives his works. It is my movement: one vertical, one horizontal, and on hope that in adopting this approach my the order of precedence between words and observations may acquire some more general images. He goes on to talk about the three relevance to Godard’s work throughout the characters whom he relates to differing abstract 1980s and beyond. vectors of movement, a theme I shall return to In embarking upon his first mainstream presently. There is little of any narrative feature since Tout va bien (1972) Godard found significance in this video-scenario beyond talk of himself faced with the problem of how to a desire to leave the big city, a desire originating incorporate something of the technical and with Denise (Miou-miou) who acts on it and conceptual flexibility and freedom which he had aspired to by Jacques (Dutronc) who lags attained as the co-director with Anne-Marie behind.1 Miéville of Sonimage, a kind of private audio- Beyond this, Godard muses on a variety of visual research institute for the production of subjects relating to the production of the film – innovative film, video and TV. -

Between Objective Engagement and Engaged Cinema: Jean- Luc

It is often argued that between 1967 and 1974 Godard operated under a misguided assessment of the effervescence of the social and political situation and produced the equivalent of “terrorism” in filmmaking. He did this, as the argument goes, by both subverting the formal operations of narrative film and by being biased 01/13 toward an ideological political engagement.1 Here, I explore the idea that Godard’s films of this period are more than partisan political statements or anti-narrative formal experimentations. The filmmaker’s response to the intense political climate that reigned during what he would retrospectively call his “leftist trip” years was based on a filmic-theoretical Irmgard Emmelhainz praxis in a Marxist-Leninist vein. Through this I t praxis, Godard explored the role of art and artists r a and their relationship to empirical reality. He P , Between ) 4 examined these in three arenas: politics, 7 9 aesthetics, and semiotics. His work between 1 - Objective 7 1967 and 1974 includes the production of 6 9 1 collective work with the Dziga Vertov Group (DVG) ( ” g until its dissolution in 1972, and culminates in Engagement n i k his collaboration with Anne-Marie Miéville under a m the framework of Sonimage, a new production m l and Engaged i company founded in 1973 as a project of F t n “journalism of the audiovisual.” a t i l ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊGodard’s leftist trip period can be bracketed Cinema: Jean- i M by two references he made to other politically “ s ’ engaged artists. In Camera Eye, his contribution d Luc Godard’s r a to the collectively-made film Loin du Vietnam of d o G 1967, Godard refers to André Breton. -

Introduction in FOCUS: Revoicing the Screen

IN FOCUS: Revoicing the Screen Introduction by TESSA DWYER and JENNIFER o’mEARA, editors he paradoxes engendered by voice on-screen are manifold. Screen voices both leverage and disrupt associations with agency, presence, immediacy, and intimacy. Concurrently, they institute artifice and distance, otherness and uncanniness. Screen voices are always, to an extent, disembodied, partial, and Tunstable, their technological mediation facilitating manipulation, remix, and even subterfuge. The audiovisual nature of screen media places voice in relation to— yet separate from—the image, creating gaps and connections between different sensory modes, techniques, and technologies, allowing for further disjunction and mismatch. These elusive dynamics of screen voices—whether on-screen or off-screen, in dialogue or voice-over, as soundtrack or audioscape— have already been much commented on and theorized by such no- tables as Rick Altman, Michel Chion, Rey Chow, Mary Ann Doane, Kaja Silverman, and Mikhail Yampolsky, among others.1 Focusing primarily on cinema, these scholars have made seminal contribu- tions to the very ways that film and screen media are conceptual- ized through their focus on voice, voice recording and mixing, and postsynchronization as fundamental filmmaking processes. Altman 1 Rick Altman, “Moving Lips: Cinema as Ventriloquism,” Yale French Studies 60 (1980): 67–79; Rick Altman, Silent Film Sound (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004); Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia Univer- sity -

Tasevska EF 2020 Final

Etudes Francophones Vol. 32 Printemps 2020 Bande dessinée et intermédialité Godard’s Contra-Bande: Early Comic Heroes in Pierrot le fou and Le Livre d’image Tamara Tasevska Northwestern University Introduction Throughout Jean-Luc Godard’s scope of work spanning over more than six decades, references to the comic strip strangely surface, seemingly unattached to any interpretative frame, creating instability and disproportion within the form of the films. Specific images of characters reading and performing Les Pieds Nickelés, or Zig et Puce appear in his early films, À Bout de souffle (1960), Une Femme est une femme (1961) and Pierrot le fou (1965), whereas in Une femme est une femme (1960), Alphaville (1965), Made in U.S.A (1966), and Tout va bien (1972), the whole of the diegetic world resembles the compositions and frames of the comic strip. In Godard’s later period, even though we witness an acute shift in register of the image, comic figures ostensibly continue to appear, drained of color, as if photocopied several times, floating free in a void of empty black space detached from any definitive meaning. Without doubt, the filmmaker uses the comic strip as Brechtian means in order to provoke distanciation effects (Sterritt 64), but I would also suggest that these instances put forward by the comic may also function to point to provocative connections between aesthetics and politics.1 Thinking of Godard’s oeuvre, in the chapter “Au-delà de l’image-mouvement” of L’image-temps, Gilles Deleuze remarks that the filmmaker drew inspiration from the comic strip at its most cruel and cutting, thus constructing a world according to “émouvantes” and “terribles” images that reach a level of autonomy in and of themselves (18-19). -

The Carlyle Society Papers

THETHE CARLYLECARLYLE SOCIETYSOCIETY PAPERSPAPERS -- SESSIONSESSION 2012-20132010-2011 NewNew SeriesSeries No.25No.23 PrintedPrinted by by– www.ed.ac.uk/printing – www.pps.ed.ac.uk THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2012-2013 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 25 • Edinburgh 2012 1 2 President’s Letter 2012 has been a momentous year, the publication of volume 40 of the Carlyle Letters a milestone celebrated in July by an international gathering in George Square in Edinburgh, and an opportunity for the Society to participate in the form of a memorable Thomas Green lecture by Lowell Frye. The 50-odd people who took part in three days’ discussions of both Carlyles ranged from many countries, and many of them were new names in Carlyle studies – a hopeful sign for the future. At the same conference, another notable step gained: many new members for the Carlyle Society, several of them life members. And many members willing to join the digital age by having their publications sent by internet – a real saving in time and cost each summer as the papers are published, and the syllabus for the new session sent out worldwide. Further members willing to receive papers in this form are invited to write in to the address below. Obviously, we will continue to produce the papers in traditional form, and many libraries continue to value their annual appearance. One further part of the celebrations of our 40th volume remains in the form of a public lecture on Thomas Carlyle and the University of Edinburgh in the David Hume Tower on 15 November 2012. By then the actual volume should be to hand from North Carolina, where Duke Press has pledged its continued support as the edition moves, hardly believably, to complete the letters that have survived between the Carlyles. -

GODARD FILM AS THEORY Volker Pantenburg Farocki/Godard

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FAROCKI/ GODARD FILM AS THEORY volker pantenburg Farocki/Godard Farocki/Godard Film as Theory Volker Pantenburg Amsterdam University Press The translation of this book is made possible by a grant from Volkswagen Foundation. Originally published as: Volker Pantenburg, Film als Theorie. Bildforschung bei Harun Farocki und Jean-Luc Godard, transcript Verlag, 2006 [isbn 3-899420440-9] Translated by Michael Turnbull This publication was supported by the Internationales Kolleg für Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. IKKM BOOKS Volume 25 An overview of the whole series can be found at www.ikkm-weimar.de/schriften Cover illustration (front): Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Chapter 4B (1988-1998) Cover illustration (back): Interface © Harun Farocki 1995 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 891 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 755 7 doi 10.5117/9789089648914 nur 670 © V. Pantenburg / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

Written and Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

FREEDOM DOESN'T COME CHEAP WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY JEAN-LUC GODARD France / 2010 / 101 min. / 1.78:1 / Dolby SR / In French w/ English subtitles A Lorber Films Release from Kino Lorber, Inc. 333 W. 39th St. Suite 503 New York, NY 10018 (212) 629-6880 Publicity Contact: Rodrigo Brandao Kino Lorber, Inc. (212) 629-6880 ext. 12 [email protected] Short synopsis A symphony in three movements. THINGS SUCH AS: A Mediterranean cruise. Numerous conversations, in numerous languages, between the passengers, almost all of whom are on holiday... OUR EUROPE: At night, a sister and her younger brother have summoned their parents to appear before the court of their childhood. The children demand serious explanations of the themes of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. OUR HUMANITIES: Visits to six sites of true or false myths: Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Hellas, Naples and Barcelona. Long synopsis A symphony in three movements. THINGS SUCH AS: The Mediterranean, a cruise ship. Numerous conversations, in numerous languages, between the passengers, almost all of whom are on holiday... An old man, a war criminal (German, French, American we don’t know) accompanied by his grand daughter... A famous French philosopher (Alain Badiou); A representative of the Moscow police, detective branch; An American singer (Patti Smith); An old French policeman; A retired United Nations bureaucrat; A former double agent; A Palestinian ambassador; It’s a matter of gold, as it was before with the Argonauts, but what is seen (the image) is very different from what is heard (the word). OUR EUROPE: At night, a sister and her younger brother have summoned their parents to appear before the court of their childhood. -

JEAN-LUC GODARD Épisodes Un Et Deux

JEAN-LUC GODARD ÉPISODES UN ET DEUX CONCEPTION ET MISE EN SCÈNE EDDY D’aranjo Jean-Luc Godard dans Caméra-oeil, 1967 LA COMPAGNIE Après eddy, performance documentaire semi-autobiographique, d’après les romans d’Édouard Louis, présenté au Théâtre National de Strasbourg en 2018, notre compagnie continue de sonder les possibilités d’un théâtre politique contemporain, et les moyens d’un accueil en son sein des voix mineures et des narrations marginales. Poursuivant notre étude de la notion d’auteur, nous proposons cette fois un portrait au long cours de Jean-Luc Godard - et à travers lui du second vingtième siècle, et de l’histoire de la gauche artistique française. Nous nous arrêterons, chemin faisant, sur quelques films marquants, émouvants et significatifs, où se mêlent l’humour et le chagrin, le désir et l’analyse - entre autres À bout de souffle, Le mépris, Caméra-oeil, La chinoise, Sauve qui peut (la vie), Histoire(s) du cinéma... Le passé et le pré- sent s’y regardent et s’y confrontent sans cesse, mêlant fiction, documentaire et performance, cherchant par l’art la vie plus ample, ou, au moins, le paysage de nos mélancolies héritées. Chacun des deux épisodes constitue un spectacle autonome. Ils peuvent être joués seuls, indépendemment l’un de l’autre, ou ensemble, dans une version intégrale. Le premier, Je me laisse envahir par le Vietnam (1930 - 1972), sera créé en janvier 2021, à La Commune, Centre Dramatique National d’Aubervilliers. Le second, J’attends la mort du cinéma (1973 -), au Théâtre National de Strasbourg, au cours de la saison 2021-2022. -

Love, Death and the Search for Community in William Gaddis And

Histoire(s) of Art and the Commodity: Love, Death, and the Search for Community in William Gaddis and Jean-Luc Godard Damien Marwood Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of English and Creative Writing The University of Adelaide December 2013 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... iii Declaration............................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Topography ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Godard, Gaddis .................................................................................................................................. 17 Commodity, Catastrophe: the Artist Confined to Earth ........................................................................... 21 Satanic and Childish Commerce / Art and Culture ............................................................................ -

Fiction and Newsreel Documentary in Godard's Cinema

Fiction and Newsreel Documentary in Godard’s Cinema PIETRO GIOVANNOLI DOCUMENTARY AND FICTION. AN EMBLEMATIC LEGEND There is a legend that Godard would have been one of the special guests in the live broadcast of the Moon landing on the First National French channel (ORTF1) and that he would have pretended that the world-wide televised images were just a really convincing fake (“ce direct est un faux”; “ce qu’on voit c’est un film monsieur”).1 These phrases, which presumably were never uttered by Godard—who, in his most violent Marxist-Maoist period, would have been a very unlikely guest for such an event—are nev- ertheless emblematic of the close relationship that Godard’s cinema main- tains with both fiction and documentary or—more specifically to the sub- ject of our volume—to newsreel cinema. A dozen years later the successful mission of the Apollo 11, Godard, guest of Jean-Luis Burgat at the live tap- 1 Guillas 2009, Hansen-Løve 2010. Following Karel 2003: 5, Godard would have expressed his doubts in the “journal de TF1”. – In an interview with A. Fleischer (director of MORCEAUX DE CONVERSATIONS AVEC JEAN-LUC GODARD), when asked if “Le commentaire de Jean-Luc Godard sur la non-vérité de l’homme sur la Lune est-il confirmé?” Fleischer answered “Godard est capable de toutes sortes de provocations, y compris sur des thèmes plus graves. On a parlé même d’une certaine forme de négationnisme chez lui. Dans ce cas, il pourrait en effet nier l’homme sur la Lune, puisque cet homme est américain” (Fleischer 2009).