L-G-0002402053-0003476196.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

ENG 494: the Essay-Film's Recycling Of

Nandini Chandra, Study Abroad Application Location Specific Course Proposal The Essay-Film’s Recycling of “Waste”: Lessons from the Left Bank *ENG 494: Study Abroad (3) The essay film shuns the mimetic mode, opting to construct a reality rather than reproduce one. Some of its signature tools in this project are: experimental montage techniques, recycling of still photographs, and the use of found footage to immerse the viewer in an alternative and yet uncannily plausible reality. Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnes Varda are three giants of this genre who shaped this playful filmic language in France. The essay-film is their paradoxical contribution to crafting a collective experience out of the minutiae of individual self-expressions. Our course will focus particularly on this trio of directors’ self-reflexive and heretical relationship with the theme of “waste”— industrial, cultural and human—which forms a central preoccupation in their films. Many of these films use the trope of travel to show wastelands created by the history of capitalist wars and colonialism. We will examine the diverse ways in which the essay-film alters our understanding of “waste” and turns it into something mysteriously productive. This in turn leads us to the question of the “surplus population”—those thrown out of the circuits of capitalist production and left to fend for themselves—as a source of potentially utopian possibilities. Capitalism’s well-known “creative destruction” is ironically paralleled by these films’ focus on the productivity of waste products, and the creative powers of capitalism’s outcastes. 1. The course will historiciZe the critical-lyrical practice of the essay-film, looking at the films themselves as well as key scholarship on essay-films. -

Envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity Christopher Butler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Butler, Christopher, "Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4648 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spectatorial Shock and Carnal Consumption: (Re)envisaging Historical Trauma in New French Extremity by Christopher Jason Butler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Film Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Amy Rust, Ph. D. Scott Ferguson, Ph. D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph. D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2013 Keywords: Film, Violence, France, Transgression, Memory Copyright © 2013, Christopher Jason Butler Table of Contents List of Figures ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Recognizing Influence -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Performance in and of the Essay Film: Jean-Luc Godard Plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre Musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork

SFC_9.1_05_art_Rascaroli.qxd 3/6/09 8:49 AM Page 49 Studies in French Cinema Volume 9 Number 1 © 2009 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/sfc.9.1.49/1 Performance in and of the Essay film: Jean-Luc Godard plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork Abstract Keywords The ‘essay film’ is an experimental, hybrid, self-reflexive form, which crosses Essay film generic boundaries and systematically employs the enunciator’s direct address to Jean-Luc Godard the audience. Open and unstable by nature, it articulates its rhetorical concerns in performance a performative manner, by integrating into the text the process of its own coming communicative into being, and by allowing answers to emerge in the position of the embodied negotiation spectator. My argument is that performance holds a privileged role in Jean-Luc authorial self- Godard’s essayistic cinema, and that it is, along with montage, the most evident representation site of the negotiation between film-maker and film, audience and film, film and Notre musique meaning. A fascinating case study is provided by Notre musique/Our Music (2004), in which Godard plays himself. Communicative negotiation is, I argue, both Notre musique’s subject matter and its textual strategy. It is through the variation in registers of acting performances that the film’s ethos of unreserved openness and instability is fully realised, and comes to fruition for its embodied spectator. In a rare scholarly contribution on acting performances in documentary cinema, Thomas Waugh reminds us that the classical documentary tradition took the notion of performance for granted; indeed, ‘semi-fictive characteri- zation, or “personalization,”… seemed to be the means for the documentary to attain maturity and mass audiences’ (Waugh 1990: 67). -

Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil

WASEDA RILAS JOURNALWaves NO. on Different4 (2016. 10) Shores: Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil Waves on Different Shores: Comparing the New Cinemas of France, Japan and Brazil Richard PEÑA Abstract What is the place of “comparative” film historiography? In an era that largely avoids over-arching narratives, what are the grounds for, and aims of, setting the aesthetic, economic or technological histories of a given national cinema alongside those of other nations? In this essay, Prof. Richard Peña (Columbia University) examines the experiences of three distinct national cinemas̶those of France, Japan and Brazil̶that each witnessed the emer- gence of new movements within their cinemas that challenged both the aesthetic direction and industrial formats of their existing film traditions. For each national cinema, three essential factors for these “new move” move- ments are discussed: (1) a sense of crisis in the then-existing structure of relationships within their established film industries; (2) the presence of a new generation of film artists aware of both classic and international trends in cinema which sought to challenge the dominant aesthetic practices of each national cinema; and (3) the erup- tion of some social political events that marked not only turning points in each nation’s history but which often set an older generation then in power against a defiant opposition led by the young. Thus, despite the important and real differences among nations as different as France, Japan and Brazil, one can find structural similarities related to both the causes and consequences of their respective cinematic new waves. Like waves, academic approaches to various dis- personal media archives resembling small ciné- ciplines seem to have a certain tidal structure: mathèques, the idea of creating new histories based on sometimes an approach is “in,” fashionable, and com- linkages between works previously thought to have monly used or cited, while soon after that same little or no connection indeed becomes tempting. -

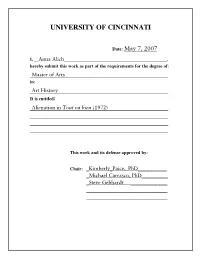

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

WILD Grasscert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES)

WILD GRASS Cert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES) A film directed by Alain Resnais Produced by Jean‐Louis Livi A New Wave Films release Sabine AZÉMA André DUSSOLLIER Anne CONSIGNY Mathieu AMALRIC Emmanuelle DEVOS Michel VUILLERMOZ Edouard BAER France/Italy 2009 / 105 minutes / Colour / Scope / Dolby Digital / English Subtitles UK Release date: 18th June 2010 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐Mail: [email protected] or FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films – [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 www.newwavefilms.co.uk WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) SYNOPSIS A wallet lost and found opens the door ‐ just a crack ‐ to romantic adventure for Georges (André Dussollier) and Marguerite (Sabine Azéma). After examining the ID papers of the owner, it’s not a simple matter for Georges to hand in the red wallet he found to the police. Nor can Marguerite retrieve her wallet without being piqued with curiosity about who it was that found it. As they navigate the social protocols of giving and acknowledging thanks, turbulence enters their otherwise everyday lives... The new film by Alain Resnais, Wild Grass, is based on the novel L’Incident by Christian Gailly. Full details on www.newwavefilms.co.uk 2 WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) CREW Director Alain Resnais Producer Jean‐Louis Livi Executive Producer Julie Salvador Coproducer Valerio De Paolis Screenwriters Alex Réval Laurent Herbiet Based on the novel L’Incident -

Film Descriptions

86325_9190_Posters_27x40_v1 2/10/14 12:52 PM Page 2 2014 FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by Brown University at the Cable Car Cinema February 20 – March 2, 2014 Le dernier des injustes (Last of the Unjust) L’ordre et la morale (Rebellion) 2014 Film synopses dir. Claude Lanzmann, France/Austria, 2013, 220 minutes dir. Mathieu Kassovitz, France, 2011, 136 minutes Sunday, Feb 23 @ 2:15 PM; Thursday, Feb 27 @ 6:30 PM Friday, Feb 21 @ 9 PM; Wednesday, Feb 26 @ 9 PM A place: Theresienstadt. A unique place of propaganda April 1988, Ouvea island, New Caledonia. Thirty police- Alceste à bicyclette (Cycling with Molière) which Adolf Eichmann called the “model ghetto,” men held hostage by a group of Kanak separatists. Three dir. Philippe Le Guay, France, 2013, 104 minutes designed to mislead the world and Jewish people regard- hundred soldiers sent from France to restore order. Two Saturday, Feb 22 @ 6:30 PM; Thursday, February 27 @ 4 PM ing its real nature, to be the last step before the gas cham- men face to face: Philippe Legorjus, captain of the GIGN Described as “A warm and winning chamber piece about ber. A man: Benjamin Murmelstein, last president of the and Alphonse Dianou, head of the hostage takers. Through two actors taking on The Misanthrope and trying not to Theresienstadt Jewish Council, a fallen hero condemned to shared values, they will try to win the dialogue. But in the strangle one another in the process,” The film follows the exile, who was forced to negotiate day after day from 1938 midst of a presidential election, when the stakes are polit- travails of TV heartthrob Gauthier Valence, who travels to until the end of the war with Eichmann, to whose trial ical, order is not always dictated by morality. -

Two Discs from Fores's Moving Panorama. Phenakistiscope Discs

Frames per second / Pre-cinema, Cinema, Video / Illustrated catalogue at www.paperbooks.ca/26 01 Fores, Samuel William Two discs from Fores’s moving panorama. London: S. W. Fores, 41 Piccadily, 1833. Two separate discs; with vibrantly-coloured lithographic images on circular card-stock (with diameters of 23 cm.). Both discs featuring two-tier narratives; the first, with festive subject of music and drinking/dancing (with 10 images and 10 apertures), the second featuring a chap in Tam o' shanter, jumping over a ball and performing a jig (with 12 images and 12 apertures). £ 350 each (w/ modern facsimile handle available for additional £ 120) Being some of the earliest pre-cinema devices—most often attributed either to either Joseph Plateau of Belgium or the Austrian Stampfer, circa 1832—phenakistiscopes (sometimes called fantascopes) functioned as indirect media, requiring a mirror through which to view the rotating discs, with the discrete illustrations activated into a singular animation through the interruption-pattern produced by the set of punched apertures. The early discs offered here were issued from the Piccadily premises of Samuel William Fores (1761-1838)—not long after Ackermann first introduced the format into London. Fores had already become prolific in the publishing and marketing of caricatures, and was here trying to leverage his expertise for the newest form of popular entertainment, with his Fores’s moving panorama. 02 Anonymous Phenakistiscope discs. [Germany?], circa 1840s. Four engraved card discs (diameters avg. 18 -

XIV:10 CONTEMPT/LE MÉPRIS (102 Minutes) 1963 Directed by Jean

March 27, 2007: XIV:10 CONTEMPT/LE MÉPRIS (102 minutes) 1963 Directed by Jean-Luc Godard Written by Jean-Luc Godard based on Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo Produced by George de Beauregard, Carlo Ponti and Joseph E. Levine Original music by Georges Delerue Cinematography by Raoul Coutard Edited by Agnès Guillemot and Lila Lakshamanan Brigitte Bardot…Camille Javal Michel Piccoli…Paul Javal Jack Palance…Jeremy Prokolsch Giogria Moll…Francesa Vanini Friz Lang…himself Raoul Coutard…Camerman Jean-Luc Godard…Lang’s Assistant Director Linda Veras…Siren Jean-Luc Godard (3 December 1930, Paris, France) from the British Film Institute website: "Jean-Luc Godard was born into a wealthy Swiss family in France in 1930. His parents sent him to live in Switzerland when the war broke out, but in the late 40's he returned to Paris to study ethnology at the Sorbonne. He became acquainted with Claude Chabrol, Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette, forming part of a group of passionate young film- makers devoted to exploring new possibilities in cinema. They were the leading lights of Cahiers du Cinéma, where they published their radical views on film. Godard's obsession with cinema beyond all else led to alienation from his family who cut off his allowance. Like the small time crooks he was to feature in his films, he supported himself by petty theft. He was desperate to put his theories into practice so he took a job working on a Swiss dam and used it as an opportunity to film a documentary on the project. -

Sharon Willis Art and Art History University of Rochester Rochester, New York 14627 (585) 275-5757/9372; (585) 473-3927 (Home) [email protected]

Sharon Willis Art and Art History University of Rochester Rochester, New York 14627 (585) 275-5757/9372; (585) 473-3927 (home) [email protected] Education Ph.D., French Literature, Cornell University B.A., Cornell University, History of Art Areas of Specialization: film history and theory, visual and cultural studies, feminist theory, comparative literature and critical theory, U. S. and French cinema. Books The Poitier Effect: Racial Melodrama and Fantasies of Reconciliation, forthcoming, University of Minnesota Press, 2015. High Contrast: Race and Gender in Popular Film (Duke University Press, 1997). Co-Editor, with Constance Penley, Male Trouble (University of Minnesota Press, 1993). Marguerite Duras: Writing on the Body (University of Illinois Press, 1987). Work In Progress Book project: “Lost and Found: World War II and Cinematic Memory.” Shock, Spectacle, Specters: Django Unchained (2012) and Twelve Years a Slave (2013).” “Precious Realism: The Help (2010), Precious (2009), and Monster’s Ball (2001).” Recent Articles and Book Chapters “Moving Pictures: Spectacles of Enslavement,” solicited for The Cambridge Companion to Slavery and American Literature,” ed., Ezra Tawil (Cambridge University Press, 2014. “Afterword,” Marguerite Duras, L’Amour, trans., Kazim Ali and Libby Murphy (Open Letter Press, 2013) 101-109. “‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater: Liquidating History in Inglourious Basterds,” in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds: Manipulations of Metacinema, ed., Robert von Dassanowsky (Continuum Press, 2012) 163-192. “2002: Movies and Melancholy” in American Cinema of the 2000s, ed., Timothy Corrigan, in the Screen Decades series (Rutgers University Press, 2012) 61-82. “Lost Objects: The Museum of Cinema,” for The Renewal of Cultural Studies, ed., Paul Smith, (Temple University Press, 2011) 93-102.