Brown Rot of Peach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

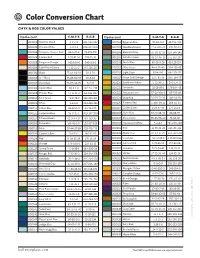

Color Conversion Chart

Color Conversion Chart CMYK & RGB COLOR VALUES Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B 000009 Reactive Cloud 4-2-1-0 241-243-247 000164 Egyptian Blue 81-48-0-0 49-116-184 000013 Opaque White 4-2-2-1 246-247-249 000203 Woodland Brown 22-63-87-49 120-70-29 000016 Turquoise Opaque Rod 65-4-27-6 75-174-179 000206 Elephant Gray 35-30-32-18 150-145-142 000024 Tomato Red 1-99-81-16 198-15-36 000207 Celadon Green 43-14-46-13 141-167-137 000025 Tangerine Orange 1-63-100-0 240-119-2 000208 Dusty Blue 60-25-9-28 83-123-154 000034 Light Peach Cream 5-12-15-0 243-226-213 000212 Olive Green 44-4-91-40 104-133-42 000100 Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000216 Light Cyan 62-4-9-0 88-190-221 000101 Stiff Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000217 Green Gold Stringer 11-6-83-13 206-194-55 000102 Blue Black 76-69-64-85 6-7-13 000220 Sunflower Yellow 5-33-99-1 240-174-0 000104 Glacier Blue 38-3-5-0 162-211-235 000221 Citronelle 35-15-95-1 179-184-43 000108 Powder Blue 41-15-11-3 153-186-207 000222 Avocado Green 57-24-100-2 125-155-48 000112 Mint Green 43-2-49-2 155-201-152 000224 Deep Red 16-99-73-38 140-24-38 000113 White 5-2-5-0 244-245-241 000225 Pimento Red 1-100-99-11 208-10-13 000114 Cobalt Blue 86-61-0-0 43-96-170 000227 Golden Green 2-24-97-34 177-141-0 000116 Turquoise Blue 56-0-21-1 109-197-203 000236 Slate Gray 57-47-38-40 86-88-97 000117 Mineral Green 62-9-64-27 80-139-96 000241 Moss Green 66-45-98-40 73-84-36 000118 Periwinkle 66-46-1-0 102-127-188 000243 Translucent White 5-4-4-1 241-240-240 000119 Mink 37-44-37-28 132-113-113 000301 Pink 13-75-22-10 -

Colours in Nature Colours

Nature's Wonderful Colours Magdalena KonečnáMagdalena Sedláčková • Jana • Štěpánka Sekaninová Nature is teeming with incredible colours. But have you ever wondered how the colours green, yellow, pink or blue might taste or smell? What could they sound like? Or what would they feel like if you touched them? Nature’s colours are so wonderful ColoursIN NATURE and diverse they inspired people to use the names of plants, animals and minerals when labelling all the nuances. Join us on Magdalena Konečná • Jana Sedláčková • Štěpánka Sekaninová a journey to discover the twelve most well-known colours and their shades. You will learn that the colours and elements you find in nature are often closely connected. Will you be able to find all the links in each chapter? Last but not least, if you are an aspiring artist, take our course at the end of the book and you’ll be able to paint as exquisitely as nature itself does! COLOURS IN NATURE COLOURS albatrosmedia.eu b4u publishing Prelude Who painted the trees green? Well, Nature can do this and other magic. Nature abounds in colours of all shades. Long, long ago people began to name colours for plants, animals and minerals they saw them in, so as better to tell them apart. But as time passed, ever more plants, animals and minerals were discovered that reminded us of colours already named. So we started to use the names for shades we already knew to name these new natural elements. What are these names? Join us as we look at beautiful colour shades one by one – from snow white, through canary yellow, ruby red, forget-me-not blue and moss green to the blackest black, dark as the night sky. -

Georgia Peach Martini

710 HUFFMAN MILL ROAD BURLINGTON NORTH CAROLINA 27215 336.584.0479 GRILL584.COM WINE, BEER & COCKTAILS Our wines have been meticulously chosen from the world’s most treasured wineries. This wine list combines familiar names along with new hidden treasures chosen exclusively for . Our balanced wine selection is designed to fully complement your dining experience. Upon your request, our knowledgeable staff will pair an appropriate wine with your meal in an effort to create a memorable and elegant dining experience. Feeaturedatured WWhiteshites Steeple Jack Chardonnay, Austrailia 5.95 24.00 The colour of pale straw with a green hue; aromas of peach, ripe melon and honeysuckle on the nose. A full, soft, stonefruit palate of peaches and nectarines intermingled with rockmelon, with a creamy texture and a lingering lime citrus fi nish. Lafage Cote Est, France 6.75 26.00 The Cotes Catalanes Cote d’Est (50% Grenache Blanc, 30% Chardonnay, 20% Marsanne, aged in stainless steel on lees) is beautifully crisp and pure, with juicy acidity giving lift to notions of buttered citrus, green herbs and honeyed minerality. Medium-bodied, lively and certainly delicious, it’s a fantastic meal starter. Feeaturedatured RRedseds Gravel Bar Alluvial Red Blend, Columbia Valley 8.95 36.00 This is a full-bodied red blend (30% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot, 15% Cabernet Franc, 10% Malbec, 10% Petit Verdot) with vibrant fl avors of dried cherries, plum, toffee, chocolate and vanilla. The structure is rich, with bold tannins extending the fi nish. Block & Tackle Cabernet Sauvignon, California 7.75 31.00 A deep ruby color with a rich nose of blackberries, raspberries and hints of pepper. -

Recommended Peach and Nectarine Varieties for Northern Utah Peaches

Recommended Peach and Nectarine Varieties for Northern LARRY A. SAGERS Thanksgiving Point Office HORTICULTURE SPECIALIST 3003 North Thanksgiving Way Utah SUTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Lehi, Utah 84043-3740 EXTENSION (801) 768-2300 Peaches HARVEST VARIETY FRUIT AND TREE REMARKS SEASON COMPACT Early Fruit is same as Redhaven. Except very dense branching habit. Bud mutation of Redhaven. REDHAVEN Medium to large fruit. Skin is golden overlaid with red. Firm yellow clear CRESTHAVEN Late freestone flesh is juicy and resists browning. Holds well on tree. Self- Fruit cans and freezes well. fertile tree of above-average hardiness. Fruit resembles Elberta with yellow skin and a slight, red blush. Yellow EARLY ELBERTA In my opinion, this is the Midseason flesh is freestone. Quality is better than Elberta. Relatively cold hardy (GLEASON) best canning peach. tree. Less subject to fruit drop. Medium to large fruit, oblong and flattened. Skin is mottled bright red. Average quality for canning Yellow, freestone flesh is coarse and soft with melting texture, good GOLDEN JUBILEE Midseason and freezing. Fruit drops quality. Tree sets heavily but thins itself. Flowers are small, not very early from tree. showy. Medium to large fruit. Skin red over greenish yellow, changing to yellow Buds are winter hardy. HALEHAVEN Midseason at maturity. Yellow, freestone flesh is juicy and flavorful. Very sweet Excellent home garden skin. Tree is vigorous and productive. Medium, nonshowy flowers. variety. Large fruit. Skin is yellow blushed with red, little fuzz. Yellow, freestone Prized for its large, high- Midseason to J.H. HALE flesh is stringy. A fine keeper with good flavor and aroma. -

Peach, Apricot, and Nectarine

Peach, Apricot, and Nectarine plantdiseasehandbook.tamu.edu/food-crops/fruit-crops/peach-apricot-and-nectarine/ Armillaria Root Rot: This can be a major disease in older orchards and replanted orchards. (See Photo) (See Section on Mushroom Root Rot) Bacterial Canker (bacterium – Pseudomonas syringae): Elongated cankers develop at the base of buds and randomly on the trunk and scaffold limbs (See Photo). Damaged areas are slightly sunken and somewhat darker in color than the surrounding bark. At both the upper and lower margins of the canker, narrow brown streaks extend into healthy tissue. As the trees break dormancy in the spring, gum is formed by the surrounding tissue and may exert enough pressure to break through the bark and flow. The area beneath the canker has a soured odor. Individual scaffolds or the entire tree usually dies shortly after leafing out in the spring. Roots are not affected. Extensive suckering (See Photo) often occurs at the tree base. The bacterium is a weak pathogen and causes serious damage only when a tree is in a dormant condition or weakened due to unfavorable growing conditions. Bacterial canker is a component in a disease complex known as Peach Tree Short Life. Trees up to 7 years old, growing on deep sandy soil are most susceptible. Avoid using high nitrogen fertilizer rates in mid to late summer. Do not encourage late fall growth. Prune when the trees are fully dormant (January and February). High dosage of a copper-containing fungicide at leaf drop has been somewhat successful. Bacterial Spot (bacterium – Xanthomonas campestris pv. pruni): Symptoms on leaves are observed first as small, circular, or irregularly shaped, pale green lesions (See Photo). -

Problem: Brown Rot of Fruit Trees - Monilinia Fructicola

Problem: Brown Rot of Fruit Trees - Monilinia fructicola Host Plants: Peach, Nectarines, Apricots, Plums, Cherries, Apples Description: The disease may affect blossoms, twigs, and fruit. Generally, there are two major infection periods of the brown rot fungus. They occur during blossom and beginning several weeks before harvest. The blossom blight phase occurs in early spring during bloom. Young petals first develop brown spots, but the blossoms quickly turn brown or black and die. Small tufts of dusty brown to gray fungal growth can be seen growing on the dead blossoms. The loss of some blossoms in the spring is not serious in itself; however, inoculum produced on the rotting blossoms serves to infect developing fruit later in the season. The fungus also may move from blighted blossoms into the twigs, causing small, elliptical cankers. In some cases, these cankers will girdle and kill twigs. Bleeding or gum production often is associated with twig cankers. The second phase of the disease occurs as fruit begins to mature. Inoculum produced on blighted blossoms, twig cankers, or from nearby wild plums infects maturing fruit. Affected fruit develops light brown spots that enlarge rapidly. The fruit may be completely rotted within a day or two. The fungus sporulates profusely on the rotting fruit, giving the peaches a dusty brown appearance. The rotting fruit shrivels to form a structure called a mummy, which is completely colonized by the brown rot fungus. These mummies may remain attached to the tree or drop to the orchard floor. Fruits thinned at or after pit hardening also provide a good medium for the fungus and are an important source of inoculum for mature fruit infection. -

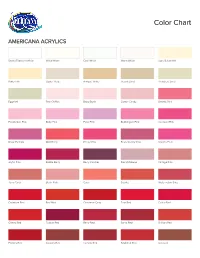

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Plums, Nectarines, Apricots, Cherries, Almonds and Prunus Hybrids

E-612 2-13 Texas Fruit and Nut Production lums, Nectarines, Apricots Cherries, Almonds and Prunus hybrids Larry Stein, Jim Kamas, and Monte Nesbitt Extension Fruit Specialists, The Texas A&M University System s closely related members of the rose family, plums and apricots typically require similar management. Both fruits have performed Amuch better in Texas than nectarines, almonds, sweet cherries, and Prunus hybrids because they are less susceptible to disease, varmints, and crop loss due to premature blooming. Plums The plum tree has white flowers and sets fruit on buds from previous season’s growth (Fig. 1). Usually Figure 1. A plum orchard in full bloom. the fruit has a dusty white coating or wax bloom that is easily rubbed off (Fig. 2). Plums can be sweet to tart; the skin is typically quite tart. The two main species used in the United States are the European plum, Prunus domestica, and the Japanese plum, Prunus salycina. The European plum includes varieties such as ‘Stanley’, which is grown for fresh fruit and often dried for use as prunes. These varieties have produced poorly in Texas because they require cold climates and are susceptible to fungal diseases such as brown rot. The varieties adapted to Texas are usually hybrids Figure 2. The dusty white coating associated with between P. domestica and P. salycina and are known plums is known as wax bloom. 1 Figure 4. Eating a ripe, juicy Figure 5. ‘Bruce’ plums. ‘Methley’ plum right off the tree. as Japanese or Japanese hybrid varieties. Most plum varieties are not self-fruitful. -

Brown Rot of Stone Fruits

EPLP-003 12/14 Brown Rot of Stone Fruits Kevin Ong, Associate Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist Corinne Rhodes, Extension Assistant* Brown rot, caused by Monilinia spp., is a common fruit may exhibit symptoms quickly or the infection disease affecting stone fruits throughout the world. may remain latent, sometimes until after harvest. There are a number of Monilinia species that cause Fruit lesions begin as light brown, circular spots on brown rot, but Monilinia fructicola is the most common the fruit surface. The spots enlarge and tan/buff clus- species affecting trees in the United States. In addition ters of spores develop, often in concentric rings (Fig. 1). to causing pre- and post-harvest brown rot of fruit, M. Infected fruit eventually completely rots, turns a tan to fructicola can cause blossom blight and stem canker. brown color, shrivels (known as mummies), and may re- Cherries, apricots, peaches, and plums are all suscepti- main attached to the tree or drop to the ground (Fig. 2). ble to the pathogen. Blossom and fruit infections can spread within High humidity, rainfall, and warm temperatures tissues to infect stems, resulting in depressed, dark-col- favor the development and spread of the disease. An ac- ored, elliptical cankers, often producing gum and tive management strategy for controlling the pathogen, sometimes spores. When stem cankers girdle or encir- involving both preventive and responsive measures, is cle the stem, they disrupt the flow of water and nutri- recommended in regions with a climate conducive to ents from the root to the stem, leading to twig dieback. -

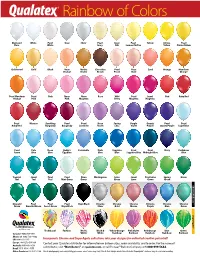

Rainbow of Colors

Rainbow of Colors Diamond White Pearl Gray Silver Pearl Ivory Pearl Yellow Citrine Pearl Clear White Ivory Silk Lemon Chiffon Yellow Citrine Yellow Goldenrod Gold Blush Neon Mocha Chocolate Pearl Rose Coral Orange Mandarin Orange Brown Brown Peach Gold Orange Pearl Mandarin Pearl Pink Neon Neon Rose Wild Pearl Jewel Red Ruby Red Orange Pink Pink Magenta Berry Magenta Magenta Pearl Maroon Sparkling Pearl Pearl Neon Spring Purple Quartz Pearl Pearl Ruby Red Burgundy Burgundy Lavender Violet Lilac Violet Purple Quartz Purple Light Blue Pearl Pale Neon Robin’s Periwinkle Dark Sapphire Pearl Pearl Navy Caribbean Azure Blue Blue Egg Blue Blue Blue Sapphire Blue Midnight Blue Blue Tropical Jewel Pearl Pearl Neon Wintergreen Lime Jewel Pearl Lime Spring Green Teal Teal Teal Mint Green Green Green Lime Green Green Chrome Balloons Chrome Emerald Pearl Pearl Pearl Onyx Black Chrome Chrome Chrome Chrome Chrome Chrome ™ Green Emerald Green Forest Green Onyx Black Silver Gold Mauve Purple Blue Green SuperAgate ® Traditional Fashion Red & Black & Yellow Orange Pink Violet Red Orange Blue Green Canada 1-800-263-6861 White White Rainbow Rainbow Rainbow Rainbow Rainbow Mexico 01-800-590-4602 UK 0800 28 12 15 Incorporate Chrome and SuperAgate collections into your designs for unlimited creative potential! Europe +44 1279 501090 Contact your Qualatex distributor for information on balloon sizes, color availability, and to order. For the name of Australia 1800-814-634 a distributor, visit “Distributors” on qualatex.com, or call Pioneer® Balloon Company at 1-800-999-5644. Brazil 55-11-4596-4555 Other Countries 316-685-2266 Due to photography and color printing processes, exact colors may vary. -

Northern Fresh Market Peach Picture

The Changing Northern New peach varieties, which are larger and Fresh Market Peach Picture redder than Red Haven, are rapidly gaining favor Bill Shane in northern peach District Fruit and Marketing Agent production areas. White Michigan State University, Benton Harbor, MI peaches are also popular. The best of these new varieties are assessed for ew varieties are the lifeblood of a White Peach and Nectarine thriving peach industry, Varieties winter hardiness, Nespecially in those states with a production and tolerance sizeable, wholesale fresh or processing White peach and nectarine variety side. In Michigan, we have seen over the options for northern wet climates to diseases in this article. last 15 years the rapid replacement of depend heavily on whether or not varieties such as ‘Cresthaven’, bacterial spot can be kept under control. ‘Glohaven’, and ‘Redskin’ by newer va- Many of the newer white peach varieties varieties with better bacterial spot rieties with greater appeal in the local and such as ‘Snow King’, ‘Sugar Giant’, and resistance. national fresh markets.’‘Red Haven’, still ‘Yukon King’ and nectarines such as the the largest acreage variety in Michigan, Arctic series are popular in California Yellow Melting Flesh Peach is losing dominance in the Michigan and drier climates (Table 2) but have Varieties peach industry. With market demand significant bacterial spot susceptibilities switching from 2 1/4” to 2 1/2” diam- that make them a challenge to grow in Many new yellow melting flesh eter peaches with over 60% red skin, and Michigan. ‘Blushingstar’ has been the peach varieties have been introduced tighter profit margins, Michigan growers best new white peach for our area in over the past 10 years as possible substi- are always looking for better alternatives. -

Good Background Colors for Readers: a Study of People with and Without Dyslexia

Good Background Colors for Readers: A Study of People with and without Dyslexia Luz Rello Jeffrey P. Bigham Human-Computer Interaction Institute Human-Computer Interaction Institute & Carnegie Mellon University Language Technologies Institute [email protected] Carnegie Mellon University [email protected] ABSTRACT The use of different background colors to enhance reading performance of those with dyslexia has been broadly dis The use of colors to enhance the reading of people with cussed in previous literature and has been recommended by dyslexia have been broadly discussed and is often recom institutions such as the British Dyslexia Association [4]. To mended, but evidence of the effectiveness of this approach is the extent of our knowledge the existing recommendations lacking. This paper presents a user study with 341 partic are not based on objectives measures collected with large ipants (89 with dyslexia) that measures the effect of using user studies. In this paper, we present the first study that background colors on screen readability. Readability was measures the impact of ten background colors on the reading measured via reading time and distance travelled by the performance. The user study was carried out with a large mouse. Comprehension was used as a control variable. The number of participants (341) with and without dyslexia, al results show that using certain background colors have a sig lowing for a statistical comparison between groups. nificant impact on people with and without dyslexia. Warm The main contributions of this study are: background colors, Peach, Orange and Yellow, significantly improved reading performance over cool background colors, - Background colors have an impact on the readability Blue, Blue Grey and Green.