Chapter One Nigeria's Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

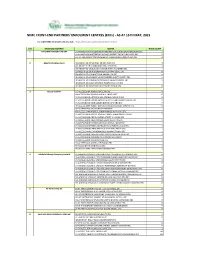

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Property Valuation

VALUATION LIST OF PROPERTIES - FIRST BATCH (APRIL 2019) S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value Number Number Number 1 0040000278 KRV/TR/J/19/001 0 KOLOME PLAZA SHOPPING MALL/ COMMERCIAL not available, ANGWAN DOKA NEW N448,000.00 108 0030000220 KRV/TR/E/19/013 ALHAJI SHEHU LADY COMFORT SMALL SHOPS COMMERCIAL 0, VINTAGE ESTATE ROAD, CITY N192,000.00 DUNAMIS BOUNDARY,CUSTOM PLAZA NYANYA, ALONG KEFFI ABUJA HAIR COLLEGE MARARABA, MARARABA STREET,MAMMY WAY,BESIDE BENEDAN EXPRESS WAY, NEW NYANYA 109 0030000170 KRV/TR/E/19/002 ALHAJI,SHOPS SHOPS OPPOSITE SMALL SHOPS COMMERCIAL 01, OPPOSITE BOREHOLE OFF N144,000.00 ROAD MARARABA APARTMENT., MARARABA 2 0060000804 KRV/TR/M/19/001 0060000804 MULTI-PURPOSE MIXED USE not available, NOT AVAILABLE, N494,400.00 BOREHOLE SAMAILA MANAGER STREET, BOUNDARY, MASAKA SAMAILA MARARABA MANAGER STREET 216 0010000034 KRV/TR/D/19/001 AYINDA CLINE SHOPPING COMMERCIAL not available, BILL CLINTON N120,000.00 3 0040000154 KRV/TR/A/19/037 101 LOUNGE 101 LOUNGE GUEST HOUSE COMMERCIAL 101, OLD KARU ROAD OPPOSITE N480,000.00 COMPUTER COMPLEX PRIMARY SCHOOL NEW NYA NYA, DUDU COMPANY, MARARABA 110 0040000835 KRV/TR/E/19/0011 ALHAJI UMARU SHOPS CENTER SHOPS COMMERCIAL 0, DAN IYA STREET, MARARABA -

Ethnicity and Citizenship in Urban Nigeria: the Jos Case, 1960-2000

ETHNICITY AND CITIZENSHIP IN URBAN NIGERIA: THE JOS CASE, 1960-2000 BY SAMUEL GABRIEL EGWU B.Sc.; M.Sc. Political Science UJ/PGSS/12730/01 A thesis in the Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE, Faculty of Social Sciences Submitted to the School of Post-Graduate Studies, University of Jos, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF JOS APRIL, 2004 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the product of my own research and has been written by me. It has not been presented for a higher degree in any University. All quotations have been acknowledged and distinguished by endnotes and quotations. SAMUEL GABRIEL EGWU CERTIFICATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is usual that in accomplishing a task of this nature, one is indebted to a number of individuals whose valuable contributions in one way or the other made it possible. In this situation such individuals are so numerous that all the names cannot be mentioned. First and foremost, I would like to express my immense debt of gratitude to Professor Warisu. O. Alli, my supervisor who promptly filled the vacuum created by the exit of Professor Aaron T. Gana. Professor Alli took more than a personal interest in getting me to work, reading the manuscripts and offering very useful and productive suggestions. More than this, he continued to drum into my ears the increasing relevance of the citizenship question in the contemporary political economy of Nigeria in general and Jos in particular, as justification for completing the investigation. To him, I remain eternally grateful indeed. -

Le Nigeria Et La Suisse, Des Affaires D'indépendance

STEVE PAGE Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance Commerce, diplomatie et coopération 1930–1980 PETER LANG Analyser les rapports économiques et diplomatiques entre le Nigeria et la Suisse revient à se pencher sur des méca- nismes peu connus de la globalisation: ceux d’une relation Nord-Sud entre deux puissances moyennes et non colo- niales. Pays le plus peuplé d’Afrique, le Nigeria semblait en passe de devenir, à l’aube de son indépendance, une puissance économique continentale. La Suisse, comme d’autres pays, espérait profiter de ce vaste marché promis à une expansion rapide. Entreprises multinationales, diplo- mates et coopérants au développement sont au centre de cet ouvrage, qui s’interroge sur les motivations, les moyens mis en œuvre et les impacts des activités de chacun. S’y ajoutent des citoyens suisses de tous âges et de tous mi- lieux qui, bouleversés par les images télévisées d’enfants squelettiques durant la « Guerre du Biafra » en 1968, en- treprirent des collectes de fonds et firent pression sur leur gouvernement pour qu’il intervienne. Ce livre donne une profondeur éclairante aux relations Suisse – Nigeria, ré- cemment médiatisées sur leurs aspects migratoires, ou sur les pratiques opaques de négociants en pétrole établis en Suisse. STEVE PAGE a obtenu un doctorat en histoire contempo- raine de l’Université de Fribourg et fut chercheur invité à l’IFRA Nigeria et au King’s College London. Il poursuit des recherches sur la géopolitique du Nigeria. www.peterlang.com Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance STEVE PAGE Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance Commerce, diplomatie et coopération 1930–1980 PETER LANG Bern · Berlin · Bruxelles · Frankfurt am Main · New York · Oxford · Wien Information bibliographique publiée par «Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek» «Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek» répertorie cette publication dans la «Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e»; les données bibliographiques détaillées sont disponibles sur Internet sous ‹http://dnb.d-nb.de›. -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol

IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 55 International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) Bahir Dar- Ethiopia Vol. 4(3), S/No 15, September, 2015:55-63 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijah.v4i3.5 The Metamorphosis of Bourgeoisie Politics in a Modern Nigerian Capitalist State Uji, Wilfred Terlumun, PhD Department of History Federal University Lafia Nasarawa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Tel: +2347031870998 or +2348094009857 & Uhembe, Ahar Clement Department of Political Science Federal University Lafia, Nasarawa State-Nigeria Abstract The Nigerian military class turned into Bourgeoisie class has credibility problems in the Nigerian state and politics. The paper interrogates their metamorphosis and masquerading character as ploy to delay the people-oriented revolution. The just- concluded PDP party primaries and secondary elections are evidence that demands a verdict. By way of qualitative analysis of relevant secondary sources, predicated on the Marxian political approach, the paper posits that the capitalist palliatives to block the Nigerian people from freeing themselves from the shackles of poverty will soon be a Copyright ©IAARR 2015: www.afrrevjo.net Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info IJAH VOL 4 (3) SEPTEMBER, 2015 56 thing of the past. It is our argument that this situation left unchecked would create problem for Nigeria’s nascent democracy which is not allowed to go through normal party polity and electoral process. The argument of this paper is that the on-going recycling of the Nigerian military class into a bourgeois class as messiahs has a huge possibility for revolution. -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

This Work Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution- Sharealike 4.0 International License

NIGERIA-ISRAEL RELATIONS 1960-2015 AJAO ISRAEL BABATUNDE (MATRIC NO.: RUN/HIR/15/6203) 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. NIGERIA-ISRAEL RELATIONS 1960-2015 A dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Arts in History and International Studies of Redeemer’s University, Ede AJAO Israel Babatunde (Matric No.: RUN/HIR/15/6203) 2017 Department of History and International Studies College of Humanities REDEEMER’S UNIVERSITY DECLARATION FORM FOR THE REPRODUCTION OF RESEARCH WORK NAME IN FULL – AJAO ISRAEL BABATUNDE TITLE OF DISSERTATION – NIGERIA-ISRAEL RELATIONS 1960-2015 DEGREE FOR WHICH RESEARCH WORK IS PRESENTED - Master of Arts in History and International Studies DATE OF AWARD – DECLARATION 1. I recognise that my dissertation will be made available for public reference and inter-library loan. 2. I authorise the Redeemer’s University to reproduce copies of my dissertation for the purposes of public reference, preservation and inter-library loan. 3. I understand that before any person is permitted to read, borrow or copy any part of my work, that person will be required to sign the following declaration: “I recognise that the copyright in the above mentioned dissertation rests with the author. I understand that copying the work may constitute an infringement of the author’s rights unless done with the written consent of the author or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act which expressly permits copying without the author’s consent. I further understand that no information derived from this work may be published without acknowledgement” 4. -

Diasporas, Remittances and Africa South of the Sahara

DIASPORAS, REMITTANCES AND AFRICA SOUTH OF THE SAHARA A STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT MARC-ANTOINE PÉROUSE DE MONTCLOS ISS MONOGRAPH SERIES • NO 112, MARCH 2005 CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR iv GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 5 African diasporas and homeland politics CHAPTER 2 27 The political value of remittances: Cape Verde, Comores and Lesotho CHAPTER 3 43 The dark side of diaspora networking: Organised crime and terrorism CONCLUSION 65 iv ABOUT THE AUTHOR Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos is a political scientist with the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD). He works on forced migrations and has published various books on the issue, especially on Somali refugees (Diaspora et terrorisme, 2003). He lived for several years in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya, and conducted field investigations in the Comores, Cape Verde and Lesotho in 2002 and 2003. This study is the result of long-term research on the subject. v GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS ANC: African National Congress BCP: Basotho Congress Party BNP: Basotho National Party COSATU: Congress of South African Trade Unions ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States FRELIMO: Frente de Libertação de Moçambique GDP: Gross Domestic Product GNP: Gross National Product INAME: Instituto Nacional de Apoio ao Emigrante Moçambicano no Exterior IOM: International Organisation for Migration IRA: Irish Republican Army LCD: Lesotho Congress for Democracy LLA: Lesotho Liberation Army LTTE: Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam MASSOB: Movement for the Actualisation -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

AC Vol 41 No 21

www.africa-confidential.com 27 October 2000 Vol 41 No 21 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL NIGERIA I 2 NIGERIA Power and greed Privatisation is keenly favoured by High street havens foreigners and for different reasons The search for Abacha’s stolen money has led to several major by Nigeria’s business class. Western banks and is at last forcing their governments to act President Obasanjo’s sell-off plans are gathering steam but donors Investigators pursuing some US$3 billion of funds stolen by the late General Sani Abacha’s regime complain of delays and worry about between 1993-98 have established that the cash was deposited in more than 30 major banks in state favouritism. Britain, Germany, Switzerland and the United States without any intervention from those countries’ financial regulators. The failure of the regulators to act even after specific banks and NIGERIA II 3 corporate accounts were named in legal proceedings in Britain and congressional hearings in the USA points to a lack of will by Western governments to crack down on corrupt transfers (AC Vol Oduduwa’s children 40 No 23). Quarrels between different departments - with trade and finance officials trying to block any public disclosure of the illicit flows - delayed government action. None of the banks named so President Obasanjo’s efforts to reestablish the nation are at risk far as accepting deposits from Abacha’s family and associates - Australia and New Zealand from violence involving its two Banking Group, Bankers Trust, Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Merrill Lynch, biggest ethnic groups, the Yoruba National Westminster Bank and Paribas - have been formally investigated nor had any disciplinary and the Hausa-Fulani.