Vocabulary Borrowing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Small Details Group Dining & Events

THE SMALL DETAILS GROUP DINING & EVENTS AT DRAGONFLY SUSHI & SAKÉ COMPANY WE ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATING MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS. Our group dining packages are designed to help you build stronger friendships, celebrate memories and bring out the very best in your group as they gather around the table at Dragonfly. DRAGONFLY 3 THE SMALL DETAILS - CONTENTS FOOD MENUS Fresh selections SHOGUN MENU EMPEROR MENU from farm and sea IZAKAYA FAMILY STYLE IZAKAYA FAMILY STYLE prepared Izakaya (family) style. Creating artful flavors. Anchoring your event. Izakaya is a tapas-style dining Izakaya is a tapas-style dining Sewing friendships tighter. experience that encourages joy experience that encourages joy BEVERAGE MENU Bringing your friends, colleagues, and fulfillment through and fulfillment through family closer together. sharing and conversation. sharing and conversation. Spirited concoctions and unexpected combinations to lighten the mood. 4 guest minimum 4 guest minimum Setting the scene for an evening of relaxation, enjoyment and conversation. $65 $85 $22 $24 $27 $32 PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 6-7 * per person price does not include 20% gratuity and 7% sales tax Looking for a more exclusive experience? Total buyouts, private luncheons & sushi classes are available, please contact us for more details. DRAGONFLY 4 IZAKAYA-SHOGUN MENU STARTERS SUSHI BUTTER SAUTÉED EDAMAME CLASSIC ROLL togarashi, sea salt, bonito flakes baked, tuna, albacore, seasonal white fish, scallions, spicy sauce, eel sauce SHISO PRETTY tuna tartare, scallion, spicy mayo— COBRA KAI ROLL wrapped in shiso leaf & flash fried krab delight, red onion, tomato, tempura flakes, lemon, salmon, WONTONS garlic-shiso pesto, aged balsamic krab, cream cheese, peach-apricot reduction “THE BOMB” ROLL tuna, tempura shrimp, krab delight, BEEF TATAKI avocado, tempura flakes, eel sauce, seared n.y. -

Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan

The Numata Conference on Buddhist Studies: Violence, Nonviolence, and Japanese Religions: Past, Present, and Future. University of Hawaii, March 2014. Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan Mickey Adolphson University of Alberta 2014 What is religious violence and why is it relevant to us? This may seem like an odd question, for 20–21, surely we can easily identify it, especially considering the events of 9/11 and other instances of violence in the name of religion over the past decade or so? Of course, it is relevant not just permission March because of acts done in the name of religion but also because many observers find violence noa, involving religious followers or justified by religious ideologies especially disturbing. But such a ā author's M notion is based on an overall assumption that religions are, or should be, inherently peaceful and at the harmonious, and on the modern Western ideal of a separation of religion and politics. As one Future scholar opined, religious ideologies are particularly dangerous since they are “a powerful and Hawai‘i without resource to mobilize individuals and groups to do violence (whether physical or ideological of violence) against modern states and political ideologies.”1 But are such assumptions tenable? Is a quote Present, determination toward self-sacrifice, often exemplified by suicide bombers, a unique aspect of not violence motivated by religious doctrines? In order to understand the concept of “religious do Past, University violence,” we must ask ourselves what it is that sets it apart from other violence. In this essay, I the and at will discuss the notion of religious violence in the premodern Japanese setting by looking at a 2 paper Religions: number of incidents involving Buddhist temples. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Part 3 TRADITIONAL JAPANESE CUISINE

Part 3 TRADITIONAL JAPANESE CUISINE Chakaiseki ryori is one of the three basic styles of traditional Japanese cooking. Chakaiseki ryori (the name derives from that of a warmed stone that Buddhist monks placed in the front fold of their garments to ward off hunger pangs) is a meal served during a tea ceremony. The foods are fresh, seasonal, and carefully prepared without decoration. This meal is then followed by the tea ceremony. (Japan, an Illustrated Encyclopedia , 1993, p. 1538) Honzen ryori is one of the three basic styles of traditional Japanese cooking. Honzen ryori is a highly ritualized form of serving food in which prescribed types of food are carefully arranged and served on legged trays (honzen). Honzen ryori has its main roots in the so- called gishiki ryori (ceremonial cooking) of the nobility during the Heian period (794 - 1185). Although today it is seen only occasionally, chiefly at wedding and funeral banquets, its influence on modern Japanese cooking has been considerable. The basic menu of honzen ryori consists of one soup and three types of side dishes - for example, sashimi (raw seafood), a broiled dish of fowl or fish (yakimono), and a simmered dish (nimono). This is the minimum fare. Other combinations are 2 soups and 5 or 7 side dishes, or 3 soups and 11 side dishes. The dishes are served simultaneously on a number of trays. The menu is designed carefully to ensure that foods of similar taste are not served. Strict rules of etiquette are followed concerning the eating of the food and drinking of the sake. -

Menupro Dinner 2020

RED WINE BY THE GLASS Cabernet, Roth Estates, Alexander Valley ................................. $13 Pinot Noir, Acrobat, Oregon ........................................................ $11 Cabernat Sauvignon, Alexander Valley ...................................... $10 Bordeaux Rouge, Chateau Recougne ............................................ $9 Super Tuscan, Tommasi "Poggio Al Tufo" .................................. $8 Rioja Tempranillo, Equia, Spain ...................................................... $7 Malbec, Pascual Toso Agentina ...................................................... $7 Merlot, Hayes Ranch California ..................................................... $7 Cabernet Sauvignon, Bodega Norton Agentina ......................... $7 WHITE WINE BY THE GLASS Sauvignon Blanc, J. Christopher Willamette Valley ............... $12 Chardonnay, Ferrari Carano Alexander Valley ........................ $12 Dry Riesling, Trefethen Estate Napa .......................................... $11 Pinot Gris, Ponzi Vineyards, Willamette Valley ........................ $10 Pinot Grigio, Marco Felluga, Collio, Italy .................................... $9 Dry Riesling , Dr. loosen, Mosel Germanay .............................. $9 Chardonnay unoak, Lincourt Santa Barbara ............................... $8 Gewurztraminer, Villa Wolf Germany ......................................... $8 Chardonnay, Guenoc Lake County CA ....................................... $7 Rose, Gassier, Provence ................................................................ -

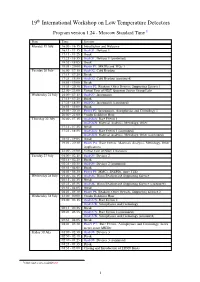

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - Moscow Standard Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 16:00 - 16:15 Introduction and Welcome 16:15 - 17:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O3: Instruments 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 20:00 - 21:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Tuesday 27 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 03:55 - 04:05 Break 04:05 - 05:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Wednesday 28 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting -

ACS42 01Kidder.Indd

The Vicissitudes of the Miroku Triad in the Lecture Hall of Yakushiji Temple J. Edward Kidder, Jr. The Lecture Hall (Ko¯do¯) of the Yakushiji in Nishinokyo¯, Nara prefecture, was closed to the public for centuries; in fact, for so long that its large bronze triad was almost forgotten and given little consideration in the overall development of the temple’s iconography. Many books on early Japanese Buddhist sculpture do not mention these three images, despite their size and importance.1) Yakushiji itself has given the impression that the triad was shielded from public view because it was ei- ther not in good enough shape for exhibition or that the building that housed it was in poor repair. But the Lecture Hall was finally opened to the public in 2003 and the triad became fully visible for scholarly attention, a situation made more intriguing by proclaiming the central image to be Maitreya (Miroku, the Buddha of the Fu- ture). The bodhisattvas are named Daimyo¯so¯ (on the Buddha’s right: Great wondrous aspect) and Ho¯onrin (left: Law garden forest). The triad is ranked as an Important Cultural Property (ICP), while its close cousin in the Golden Hall (K o n d o¯ ), the well known Yakushi triad (Bhais¸ajya-guru-vaidu¯rya-prabha) Buddha, Nikko¯ (Su¯ryaprabha, Sunlight) and Gakko¯ (Candraprabha, Moonlight) bodhisattvas, is given higher rank as a National Treasure (NT). In view of the ICP triad’s lack of exposure in recent centuries and what may be its prior mysterious perambulations, this study is an at- tempt to bring together theories on its history and provide an explanation for its connection with the Yakushiji. -

Beer Draught Draught Sake & Spirits Sake Junmai Daiginjo Ginjo Specialty Cocktails Mexico Asia Sumo Classics Sparkling

BEER DRAUGHT BLUE MOON | 6 COORS LIGHT | 6 KIRIN | 7 NEGRA MODELO | 7 PACIFICO | 7 SAPPORO | 7 805 CERVEZA | 7 LAGUNITAS IPA | 7 ‘MAKE IT’ A CUCUMBER AGUACHILE MICHELADA | 3 DRAUGHT SAKE & SPIRITS SHO CHIKU BAI — HOT SAKE (3 OZ/9 OZ CARAFE) | 6/17 PATRON SILVER | 12 TITOS | 12 SAKE JUNMAI SWORD OF THE SUN TOKUBETSU HONJOZO 300ML | 32 BAN RYU HONJOZO 720ML | 8/22/50 TOZAI LIVING JEWEL 720ML | 32 DANCE OF THE DISCOVERY* 720ML | 54 JOTO ‘THE GREEN ONE’ 720ML | 46 HIRO ‘BLUE’ JUNMAI GINJO 300ML | 6/26 TY KU SILVER 720ML | 7/20/40 KUROSAWA 720ML | 60 WATER GOD 720ML | 90 DAIGINJO JOTO ‘ONE WITH CLOCKS’ 720ML | 72 BIG BOSS 720ML | 90 SILENT STREAM 720ML | 250 PURE DAWN 720ML | 15/30/60 GINJO CABIN IN THE WOODS 720ML | 10/36/72 FUKUCHO ‘MOON ON THE WATER’ 720ML | 78 KANBARA ‘BRIDE OF THE FOX’ 720ML | 70 DEMON SLAYER 720ML | 120 RIHAKU ‘WANDERING POETS’ 720ML | 58 TOSATURU DEEP WATER AZURE 7 720ML | 12/34/70 SPECIALTY HOU HOU SHU SPARKLING 300ML | 33 JOTO ‘THE BLUE ONE’ NIGORI 720ML | 62 RIHAKU ‘DREAMY CLOUDS’ NIGORI 720ML | 68 MOONSTONE COCONUT LEMONGRASS 750ML | 7/22/45 BLOSSOM OF PEACE 720ML | 38 SAYURI ‘WHITE CRANE’ NIGORI 720ML | 8/22/50 COCKTAILS MEXICO BUBBLES AND FLOWERS | 14 Passion fruit, champagne, hibiscus + butterfly pea flower MEXICAN SWIZZLE | 16 Tequila silver, Ancho Reyes, Mr. Black, watermelon + cinnamon syrup OAXACAN OLD FASHIONED | 16 Reposado tequila, amaro liquor aperitif + demerara simple syrup ASIA MUCHO GRANDE UMAMI MARTINI | 18 Enoki mushroom infused japanese gin, dry sake, Pocari sweat water KEMURI | 16 Japanese whiskey, -

A5 MENU GENERIC SUMMER 2019 FINAL.Indd

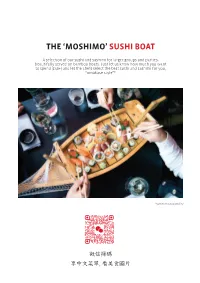

THE ‘MOSHIMO’ SUSHI BOAT A selection of our sushi and sashimi for larger groups and parties, beautifully served on bamboo boats. Just let us know how much you want to spend (£40+) and let the chefs select the best sushi and sashimi for you, “omakase-style”* *subject to availability 微信掃碼 享中文菜單,看美食圖片 HOMEMADE JUICES & DRINKS WHITE WINE RED WINE We make our own homemade drinks, because they’re healthier and tastier - and Cuvee Jean Paul, Cotes De Gasgogne, Cuvee Jean Paul, Vaucluse, we’re through with unnecessary packaging France (vgn) £4.75/ £6.80/£19.90 France (vgn) £4.75/£6.80/£19.90 Fragrant nose with refreshing and zesty Grenache, Syrah and Merlot combine to give Fresh juice of the day (vgn) £4.50 green and citrus fruit flavours, a light this wine a soft, round and easy, gentle fruit appertif white that suits delicate spices style and a little spice on the finish Freshly made lemonade (vgn) £3.90 Les Oliviers Sauvignon Blanc Vermentino, Merlot Mourvedre, Les Oliviers, Ginger & lemon iced tea (vgn) £3.90 France (vgn) £5.35/£7.75/£22.40 France (vgn) £5.35/£7.75/£22.40 Zesty grapefruit character and a ripe full Soft and round with a touch of wild red Matcha iced tea (vgn) £3.50 texture balance berry and plum fruit flavours chosen to go with all but our most delicately flavoured of Matcha rice milk shake (vgn) £3.85 Fedele Catarratto Pinot Grigio, Sicily dishes Our own homemade rice milk mixed Italy (vgn/organic) £5.95/£8.55/£24.90 with the powdered green tea leaf used in Light, dry and a little ‘nutty’ a classic Italian Barbera Ceppi Storici, Italy (vgn) £24.90 Japanese tea ceremonies. -

Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality Religion and Society

Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality Religion and Society Edited by Gustavo Benavides, Frank J. Korom, Karen Ruffle and Kocku von Stuckrad Volume 64 Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality New Approaches Edited by Birgit Kellner ISBN 978-3-11-041153-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041308-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041314-4 ISSN 1437-5370 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941312 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Birgit Kellner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston This book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Birgit Kellner 1 Introduction 1 Ingo Strauch 2 Buddhism in the West? Buddhist Indian Sailors on Socotra (Yemen) and the Role of Trade Contacts in the Spread of Buddhism 15 Anna Filigenzi 3 Non-Buddhist Customs of Buddhist People: Visual and Archaeological Evidence from North-West Pakistan 53 Toru Funayama 4 Translation, Transcription, and What Else? Some Basic Characteristics of Chinese Buddhist Translation as a Cultural Contact between India and China, with Special Reference to Sanskrit ārya and Chinese sheng 85 Lothar Ledderose 5 Stone Hymn – The Buddhist Colophon of 579 Engraved on Mount Tie, Shandong 101 Anna Andreeva 6 “To Overcome the Tyranny of Time”: Stars, Buddhas, and the Arts of Perfect Memory at Mt. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0212460 A1 Inoue Et Al

US 20070212460A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0212460 A1 Inoue et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 13, 2007 (54) COMPOSITIONS CONTAINING SUCRALOSE Nov. 25, 1998 (JP)...................................... 1198-333948 AND APPLICATION THEREOF Nov. 30, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-34O274 Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-3534.89 (75) Inventors: Maki Inoue, Osaka (JP); Kazumi Iwai, Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-3534.90 Osaka (JP): Naoto Ojima, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3534.92 Takuya Kawai, Osaka (JP); Mitsumi Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353495 Kawamoto, Osaka (JP); Shunsuke Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353496 Kuribi, Osaka (JP); Miho Sakaguchi, Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353498 Osaka (JP); Chie Sasaki, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3534.99 Kazuhito Shizu, Osaka (JP); Mariko Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3535O1 Shinguryou, Osaka (JP); Kazutaka Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353503 Hirao, Osaka (JP); Miki Fujii, Osaka Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353504 (JP); Yoshito Morita, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353505 Nobuharu Yasunami, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353507 Junko Yoshifuji, Osaka (JP) Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16984 Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16989 Correspondence Address: Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16996 SUGHRUE, MION, ZINN, MACPEAK & Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158511 SEAS, PLLC Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158523 2100 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158529 Washington, DC 20037-3202 (US) Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158536 Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158543 (73) Assignee: SAN-E GEN F.F.I., INC Apr. 6, 1999 (JP) 1999-158545 Apr.