Kaikei's Statue of Hachiman in T#Daiji Christine Guth Kanda Artibus Asiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii

The Japanese and Okinawan American Communities and Shintoism in Hawaii: Through the Case of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʽI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2012 By Sawako Kinjo Thesis Committee: Dennis M. Ogawa, Chairperson Katsunori Yamazato Akemi Kikumura Yano Keywords: Japanese American Community, Shintoism in Hawaii, Izumo Taishayo Mission of Hawaii To My Parents, Sonoe and Yoshihiro Kinjo, and My Family in Okinawa and in Hawaii Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to my committee chair, Professor Dennis M. Ogawa, whose guidance, patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge have provided a good basis for the present thesis. I also attribute the completion of my master’s thesis to his encouragement and understanding and without his thoughtful support, this thesis would not have been accomplished or written. I also wish to express my warm and cordial thanks to my committee members, Professor Katsunori Yamazato, an affiliate faculty from the University of the Ryukyus, and Dr. Akemi Kikumura Yano, an affiliate faculty and President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Japanese American National Museum, for their encouragement, helpful reference, and insightful comments and questions. My sincere thanks also goes to the interviewees, Richard T. Miyao, Robert Nakasone, Vince A. Morikawa, Daniel Chinen, Joseph Peters, and Jikai Yamazato, for kindly offering me opportunities to interview with them. It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible. -

Territoriality by Folk Boundaries and Social-Geographical Conditions in Shinto-Buddhist, Catholic, and Hidden Christian Rural Communities on Hirado Island, Western Japan

Geographical Review of Japan Series B 92(2): 51–71 (2019) Original Article The Association of Japanese Geographers Territoriality by Folk Boundaries http://www.ajg.or.jp and Social-Geographical Conditions in Shinto-Buddhist, Catholic, and Hidden Christian Rural Communities on Hirado Island, Western Japan IMAZATO Satoshi Faculty of Humanities, Kyushu University; Fukuoka 819–0395, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] Received December 10, 2018; Accepted November 24, 2019 Abstract This article explores how the sense of territoriality and various background conditions of Japanese rural communities affect the emergence of folk boundaries, which are viewed here as the contours of residents’ cognitive territory represented by religion-based symbolic markers. Specifically, I look at how the particular social-geograph- ical conditions of different communities create diverse conceptions of such boundaries, including the presence or absence of the boundaries, within the same region. Here, I focus on three Japanese villages encompassing seven local religious communities of Shinto-Buddhists, Catholics, and former Hidden Christians on Hirado Island in Kyushu. These villages are viewed respectively as examples of contrastive coexistence, degeneration, and expansion in territoriality. Among the seven religious communities, only those believing in Shinto-Buddhism, as well as Hid- den Christianity, have maintained their folk boundaries. These communities satisfy the conditions of an agglomer- ated settlement form, a size generally larger than ten households, a location isolated from other communities within the village, and strong social integration. In contrast, Catholics have not constructed such boundaries based on their historical process of settlement. However, they have influenced the forms of Shinto-Buddhists’ territoriality, although not those of Hidden Christians. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

“Modernization” of Buddhist Statuary in the Meiji Period

140 The Buddha of Kamakura The Buddha of Kamakura and the “Modernization” of Buddhist Statuary in the Meiji Period Hiroyuki Suzuki, Tokyo Gakugei University Introduction During Japan’s revolutionary years in the latter half of the nineteenth century, in particular after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, people experienced a great change in the traditional values that had governed various aspects of their life during the Edo period (1603-1867). In their religious life, Buddhism lost its authority along with its economic basis because the Meiji government, propagating Shintoism, repeatedly ordered the proclamation of the separation of Shintoism and Buddhism after the Restoration. The proclamation brought about the anti-Buddhist movement haibutsu kishaku and the nationwide movement doomed Buddhist statuary to a fate it had never before met.1 However, a number of statues were fortunately rescued from destruction and became recognized as sculptural works of Buddhist art in the late 1880s. This paper examines the change of viewpoints that occurred in the 1870s whereby the Buddha of Kamakura, a famous colossus of seated Amida (Amitâbha) from the mid-thirteenth century, was evaluated afresh by Western viewers; it also tries to detect the thresholds that marked the path toward a general acceptance of the idea that Buddhist statuary formed a genre of sculptural works in the fine arts during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Buddhist statuary in the 1870s It is widely known that the term bijutsu was coined in 1872, when the Meiji government translated the German words Kunstgewerbe (arts and crafts) and bildende Kunst (fine arts) in order to foster nationwide participation in the Vienna World Exposition of 1873. -

Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan

The Numata Conference on Buddhist Studies: Violence, Nonviolence, and Japanese Religions: Past, Present, and Future. University of Hawaii, March 2014. Discourses on Religious Violence in Premodern Japan Mickey Adolphson University of Alberta 2014 What is religious violence and why is it relevant to us? This may seem like an odd question, for 20–21, surely we can easily identify it, especially considering the events of 9/11 and other instances of violence in the name of religion over the past decade or so? Of course, it is relevant not just permission March because of acts done in the name of religion but also because many observers find violence noa, involving religious followers or justified by religious ideologies especially disturbing. But such a ā author's M notion is based on an overall assumption that religions are, or should be, inherently peaceful and at the harmonious, and on the modern Western ideal of a separation of religion and politics. As one Future scholar opined, religious ideologies are particularly dangerous since they are “a powerful and Hawai‘i without resource to mobilize individuals and groups to do violence (whether physical or ideological of violence) against modern states and political ideologies.”1 But are such assumptions tenable? Is a quote Present, determination toward self-sacrifice, often exemplified by suicide bombers, a unique aspect of not violence motivated by religious doctrines? In order to understand the concept of “religious do Past, University violence,” we must ask ourselves what it is that sets it apart from other violence. In this essay, I the and at will discuss the notion of religious violence in the premodern Japanese setting by looking at a 2 paper Religions: number of incidents involving Buddhist temples. -

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

Art of Zen Buddhism Zen Buddhism, Which Stresses a Connection to The

Art of Zen Buddhism Zen Buddhism, which stresses a connection to the spiritual rather than the physical, was very influential in the art of Kamakura Japan. Zen Calligraphy of the Kamakura Period Calligraphy by Musō Soseki (1275–1351, Japanese zen master, poet, and calligrapher. The characters "別無工夫 " ("no spiritual meaning") are written in a flowing, connected soshō style. A deepening pessimism resulting from the civil wars of 12th century Japan increased the appeal of the search for salvation. As a result Buddhism, including its Zen school, grew in popularity. Zen was not introduced as a separate school of Buddhism in Japan until the 12th century. The Kamakura period is widely regarded as a renaissance era in Japanese sculpture, spearheaded by the sculptors of the Buddhist Kei school. The Kamakura period witnessed the production of e- maki or painted hand scrolls, usually encompassing religious, historical, or illustrated novels, accomplished in the style of the earlier Heian period. Japanese calligraphy was influenced by, and influenced, Zen thought. Ji Branch of Pure Land Buddhism stressing the importance of reciting the name of Amida, nembutsu (念仏). Rinzai A school of Zen buddhism in Japan, based on sudden enlightenment though koans and for that reason also known as the "sudden school". Nichiren Sect Based on the Lotus Sutra, which teaches that all people have an innate Buddha nature and are therefore inherently capable of attaining enlightenment in their current form and present lifetime. Source URL: https://www.boundless.com/art-history/japan-before-1333/kamakura-period/art-zen-buddhism/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth406#4.3.1 Attributed to: Boundless www.saylor.org Page 1 of 2 Nio guardian, Todai-ji complex, Nara Agyō, one of the two Buddhist Niō guardians at the Nandai-mon in front of the Todai ji in Nara. -

Tokorozawa, Saitama

Coordinates: 35°47′58.6″N 139°28′7″E Tokorozawa, Saitama T okorozawa ( 所沢市 Tokorozawa-shi) is a city located in Saitama Prefecture, Tokorozawa Japan. As of 1 February 2016, the city had an estimated population of 335,968, 所沢市 and a population density of 4660 persons per km². Its total area is 7 2.11 square kilometres (27 .84 sq mi). Special city Contents Geography Surrounding municipalities Climate History Economy Public sector Private sector Central Tokorozawa from Hachikokuyama Education Transportation Railway Highway Twin towns and sister cities Flag Local attractions Seal Professional sports teams General points of interest Historical points of interest Events Notable people from Tokorozawa Tokorozawa in popular culture References External links Location of Tokorozawa in Saitama Prefecture Geography Located in the central part of the Musashino Terrace, about 30 km west of central Tokyo. Tokorozawa can be considered part of the greater Tokyo area; its proximity to the latter and lower housing costs make it a popular bedroom community. Most of Lake Sayama falls within city boundaries; Lake Tama also touches the south-western part of the city. The area around Tokorozawa Station's west exit is built up as a shopping district with several department stores. Prope Tokorozawa Street is a popular shopping arcade. Surrounding municipalities Location of Tokorozawa in Saitama Prefecture Saitama Prefecture Coordinates: 35°47′58.6″N 139°28′7″E Iruma Niiza Country Japan Sayama Region Kantō Kawagoe Prefecture Saitama Prefecture Miyoshimachi Government -

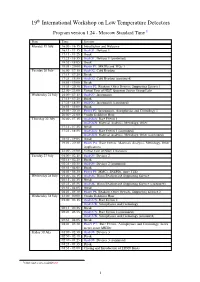

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - Moscow Standard Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 16:00 - 16:15 Introduction and Welcome 16:15 - 17:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O3: Instruments 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 20:00 - 21:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Tuesday 27 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 03:55 - 04:05 Break 04:05 - 05:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Wednesday 28 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting -

ACS42 01Kidder.Indd

The Vicissitudes of the Miroku Triad in the Lecture Hall of Yakushiji Temple J. Edward Kidder, Jr. The Lecture Hall (Ko¯do¯) of the Yakushiji in Nishinokyo¯, Nara prefecture, was closed to the public for centuries; in fact, for so long that its large bronze triad was almost forgotten and given little consideration in the overall development of the temple’s iconography. Many books on early Japanese Buddhist sculpture do not mention these three images, despite their size and importance.1) Yakushiji itself has given the impression that the triad was shielded from public view because it was ei- ther not in good enough shape for exhibition or that the building that housed it was in poor repair. But the Lecture Hall was finally opened to the public in 2003 and the triad became fully visible for scholarly attention, a situation made more intriguing by proclaiming the central image to be Maitreya (Miroku, the Buddha of the Fu- ture). The bodhisattvas are named Daimyo¯so¯ (on the Buddha’s right: Great wondrous aspect) and Ho¯onrin (left: Law garden forest). The triad is ranked as an Important Cultural Property (ICP), while its close cousin in the Golden Hall (K o n d o¯ ), the well known Yakushi triad (Bhais¸ajya-guru-vaidu¯rya-prabha) Buddha, Nikko¯ (Su¯ryaprabha, Sunlight) and Gakko¯ (Candraprabha, Moonlight) bodhisattvas, is given higher rank as a National Treasure (NT). In view of the ICP triad’s lack of exposure in recent centuries and what may be its prior mysterious perambulations, this study is an at- tempt to bring together theories on its history and provide an explanation for its connection with the Yakushiji. -

Matsuhisa H Rin's View of the Identity of Busshi (Buddhist Image Carver)

Matsuhisa H!rin ’s View of the Identity of Busshi (Buddhist Image Carver) Alin Gabriel Tirtara 1 Graduate School of Language and Culture, Osaka University Abstract This paper investigates the thinking of modern Buddhist image carvers (Jp. Ö busshi) by focusing on the Dai-busshi Matsuhisa H !rin (1901-1987), who can be considered one of the most important modern representatives of this traditional occupation. In doing so, we pursued two main tasks. The first was to place Matsuhisa in a historical context and to identify the main sources and influences on his ideas regarding art, religion, and Japanese identity that lie at the basis of his thinking. These are the ideas that helped Matsuhisa construct an image of Japanese culture in opposition to Western culture on the one hand, and of Japanese Buddhist sculpture in opposition to Western sculpture, on the other. The second task was to shed light on how Matsuhisa linked the identity of busshi with the need to protect and pass down to the next generation what he regarded as Japanese culture and sculpture, and also on how he portrayed Buddhist image carving as a religious experience that can ultimately lead to the discovery of one’s inner Buddha nature (Jp. ). Thus, it became clear that, reflecting the more general discourse that emphasized Japanese-occidental dualism, Matsuhisa stressed the idea that Japan should act as the protector of the “spiritual civilization” of the East, centered around the idea of “selflessness,” which he regarded as being superior to the “material civilization” of the West, which focuses on the “self.” Further, Japanese Buddhist statues, he argued, were a symbol of this superiority, and therefore he considered himself to be guided by the Buddha to advocate this truth through ensuring the continuity of the Japanese Buddhist image carving tradition. -

Shinto in Nara Japan, 749-770: Deities, Priests, Offerings, Prayers, and Edicts in Shoku Nihongi

Shinto in Nara Japan, 749-770: Deities, Priests, Offerings, Prayers, and Edicts in Shoku Nihongi Ross Bender Published by PMJS Papers (23 November 2016) Premodern Japanese Studies (pmjs.org) Copyright © Ross Bender 2016 Bender, Ross. “Shinto in Nara Japan, 749-770: Deities, Priests, Offerings, Prayers, and Edicts in Shoku Nihongi.” PMJS: Premodern Japanese Studies (pmjs.org), PMJS Papers, November 2016. Note: This paper is a continuation of the thread “Shinto in Noh Drama (and Ancient Japan)” on PMJS.org listserve beginning June 14, 2016. PMJS Papers is an open-source platform for the publication of scholarly material and resources related to premodern Japan. Please direct inquiries to the editor, Matthew Stavros ([email protected]) End users of this work may copy, print, download and display content in part or in whole for personal or educational use only, provided the integrity of the text is maintained and full bibliographic citations are provided. All users should be end users. Secondary distribution or hosting of the digital text is prohibited, as is commercial copying, hiring, lending and other forms of monetized distribution without the express permission of the copyright holder. Enquiries should be directed to [email protected] Shinto in Nara Japan, 749-770: Deities, Priests, Offerings, Prayers, and Edicts in Shoku Nihongi PMJS Papers Copyright © Ross Bender 2016 Shinto has become something of a taboo word, especially in the context of discussions of ancient Japanese thought. Fundamentally of course this tendency began as a reaction to the unsavory imperialist and fascist state Shinto of prewar Japan, and to the notion that Shinto was the timeless, unchanging religion of the Japanese race.