Clark, Roland. "Reaction." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920S Romania: the Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trials of the War Criminals

TRIALS OF THE WAR CRIMINALS General Considerations The Fascist regime that ruled Romania between September 14, 1940, and August 23, 1944, was brought to justice in Bucharest in May 1946, and after a short trial, its principal leaders—Ion and Mihai Antonescu and two of their closest assistants—were executed, while others were sentenced to life imprisonment or long terms of detention. At that time, the trial’s verdicts seemed inevitable, as they indeed do today, derived inexorably from the defendants’ decisions and actions. The People’s Tribunals functioned for a short time only. They were disbanded on June 28, 1946,1 although some of the sentences were not pronounced until sometime later. Some 2,700 cases of suspected war criminals were examined by a commission formed of “public prosecutors,”2 but only in about half of the examined cases did the commission find sufficient evidence to prosecute, and only 668 were sentenced, many in absentia.3 There were two tribunals, one in Bucharest and one in Cluj. It is worth mentioning that the Bucharest tribunal sentenced only 187 people.4 The rest were sentenced by the tribunal in Cluj. One must also note that, in general, harsher sentences were pronounced by the Cluj tribunal (set up on June 22, 1 Marcel-Dumitru Ciucă, “Introducere” in Procesul maresalului Antonescu (Bucharest: Saeculum and Europa Nova, 1995-98), vol. 1: p. 33. 2 The public prosecutors were named by communist Minister of Justice Lucret iu Pătrăşcanu and most, if not all of them were loyal party members, some of whom were also Jews. -

Technical Arrangement for Joint Cooperation Between the Djibouti National Gendarmerie and the Italian Carabinieri

TECHNICAL ARRANGEMENT FOR JOINT COOPERATION BETWEEN THE DJIBOUTI NATIONAL GENDARMERIE AND THE ITALIAN CARABINIERI The Djibouti Nationai Gendarmerie and Italian Carabinieri (hereinafter referred to as "the Parties"): WHEREAS the two Parties are desirous of strengthening their cooperation in the fieids of the training and the exchange of best practices reiated to their institutionalservices; CONSIDERING that Italian Carabinieri have wide experience and expertise in the fieid of public arder management and generai security; AWARE that the Djibouti Nationai Gendarmerie is committed to enhancing capacity in public safety and generai security; RECOGNISING the need for cooperation between the Parties for their mutuai benefit in the identified areas of cooperation; HAVING REGARD to the "Agreement between the Government of the Itaiian Repubiic and the Government of the Republic of Djibouti concerning cooperation in the fieid of Defence", signedin Djibouti on 30th april 2002 and the renovation of whichis ongoing; HAVING REGARD to the exchange of Verbai Notes between the Itaiian Embassy in Addis Ababa and the Djibouti Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Internationai Cooperation, in farce since 16th February 2015, on jurisdiction of the Italian military and civilian personnei; have agreedas follows: Artide 1 OBJECTIVE This Technicai Arrangement estabiishes a framework of cooperation between the Djibouti Gendarmerie and Itaiian Carabinieri in the respective fieids of competence and expertise. The provisions of this Technical Arrangement will in no way permit the derogation from the obiigations provided for in other bilatera! or multilateral conventions or Arrangements signedby the parties' Countries. The Parties agree to pursue, to the best of their ability, mutuai cooperation along with the following terms. -

Lista Cercetătorilor Acreditaţi

Cereri aprobate de Colegiul C.N.S.A.S. Cercetători acreditaţi în perioada 31 ianuarie 2002 – 23 februarie 2021 Nr. crt. Nume şi prenume cercetător Temele de cercetare 1. ABOOD Sherin-Alexandra Aspecte privind viața literară în perioada comunistă 2. ABRAHAM Florin Colectivizarea agriculturii în România (1949-1962) Emigraţia română şi anticomunismul Mecanisme represive sub regimul comunist din România (1944-1989) Mişcări de dreapta şi extremă dreaptă în România (1927-1989) Rezistenţa armată anticomunistă din România după anul 1945 Statutul intelectualului sub regimul comunist din România, 1944-1989 3. ÁBRAHÁM Izabella 1956 în Ardeal. Ecoul Revoluţiei Maghiare în România 4. ABRUDAN Gheorghe-Adrian Intelectualitatea şi rezistenţa anticomunistă: disidenţă, clandestinitate şi anticomunism postrevoluţionar. Studiu de caz: România (1977-2007) 5. ACHIM Victor-Pavel Manuscrisele scriitorilor confiscate de Securitate 6. ACHIM Viorel Minoritatea rromă din România (1940-1989) Sabin Manuilă – activitatea ştiinţifică şi politică 7. ADAM Dumitru-Ionel Ieroschimonahul Nil Dorobanţu, un făclier al monahismului românesc în perioada secolului XX 8. ADAM Georgeta Presa română în perioada comunistă; scriitorii în perioada comunistă, deconspirare colaboratori 9. ADAMEŞTEANU Gabriela Problema „Eterul”. Europa Liberă în atenţia Securităţii Scriitorii, ziariştii şi Securitatea Viaţa şi opera scriitorului Marius Robescu 10. ADĂMOAE Emil-Radu Monografia familiei Adămoae, familie acuzată de apartenență la Mișcarea Legionară, parte a lotului de la Iași Colaborarea cu sistemul opresiv 11. AELENEI Paul Istoria comunei Cosmești, jud. Galați: oameni, date, locuri, fapte 12. AFILIE Vasile Activitatea Mişcării Legionare în clandestinitate 13. AFRAPT Nicolae Presiune şi represiune politică la liceul din Sebeş – unele aspecte şi cazuri (1945-1989) 14. AFUMELEA Ioan Memorial al durerii în comuna Izvoarele, jud. -

NATO ARMIES and THEIR TRADITIONS the Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION

NATO ARMIES AND THEIR TRADITIONS The Carabinieri Corps and the International Environment by LTC (CC) Massimo IZZO - LTC (CC) Tullio MOTT - WO1 (CC) Dante MARION The Ancient Corps of the Royal Carabinieri was instituted in Turin by the King of Sardinia, Vittorio Emanuele 1st by Royal Warranty on 13th of July 1814. The Carabinieri Force was Issued with a distinctive uniform in dark blue with silver braid around the collar and cuffs, edges trimmed in scarlet and epaulets in silver, with white fringes for the mounted division and light blue for infantry. The characteristic hat with two points was popularly known as the “Lucerna”. A version of this uniform is still used today for important ceremonies. Since its foundation Carabinieri had both Military and Police functions. In addition they were the King Guards in charge for security and honour escorts, in 1868 this task has been given to a selected Regiment of Carabinieri (height not less than 1.92 mt.) called Corazzieri and since 1946 this task is performed in favour of the President of the Italian Republic. The Carabinieri Force took part to all Italian Military history events starting from the three independence wars (1848) passing through the Crimean and Eritrean Campaigns up to the First and Second World Wars, between these was also involved in the East African military Operation and many other Military Operations. During many of these military operations and other recorded episodes and bravery acts, several honour medals were awarded to the flag. The participation in Military Operations abroad (some of them other than war) began with the first Carabinieri Deployment to Crimea and to the Red Sea and continued with the presence of the Force in Crete, Macedonia, Greece, Anatolia, Albania, Palestine, these operations, where the basis leading to the acquirement of an international dimension of the Force and in some of them Carabinieri supported the built up of the local Police Forces. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.Long.T65

Cambridge University Press 0521667380 - An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches John Binns Index More information Index Abgar the Black, king of Edessa, 98, 144 Anba Bishoy, monastery, 112 Abraham of Kashkar, 117, 149 Andrassy, Julius, 182 abu ’Ali Mansur al-Hakim, 174 Andreah, Patriarch of Antioch, 219 abu Ja’far al-Mansur, 174 Andrew of Crete, 51, 117 Acacius, Patriarch of Constantinople, 205 Andrew, St, Biblical Theology Institute, Aedesius, of Ethiopia, 145–6 Moscow, 248 Afanas’ev, Nikolai, 42 Andronicus I, Byzantine emperor, 165 Ahmed ibn Ibrahim el-Ghazi or Granj, 34 Anna Comnena, Byzantine empress, 74 Aimilianos, of Simonopetra, 243 Anselm of Canterbury, 206, 209 Akoimetoi, monastery of, 117 Anthimus, Patriarch of Constantinople, 5 Aksentejevi´c,Pavle, 105 Antioch, 1–3, 9, 14–15, 40, 43–4, 143, Alaska, 152, 154–6 148, 203, 207, 220 Albania, Church in, 17, 157, 159 Antonii Khrapovitskii, 25 Alexander, prince of Bulgaria, 183 Antony of Egypt, 108–10, 114, 119 Alexander II, Tsar of Russia, 154 Antony Bloom, Metropolitan of Sourozh, Alexander Paulus, Metropolitan of 234 Estonia, 187 Aphrahat, ‘Persian sage’, 49 Alexandria, 14, 43, 63, 71–2, 115, 144, Aquinas, Thomas, 91 146–7, 158, 169 Arabs, 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 28, 33, 66, 70, 169, Alexis II, Patriarch of Moscow, 105, 238 173, 176, 190, 204; Arab Christianity, Alexius I Comnenus, Byzantine emperor, 15, 55, 79, 146–7, 172 206–7 Armenia, Church in, 30–1, 145, 190, Alexius IV, Byzantine emperor, 207 192, 219 Alexius V, Byzantine emperor, 207 Arseniev, N., 225 al-Harith, 147 Arsenius, -

Metropolis of Bukovina of the Romanian Orthodox Church (Interwar Period)

История 131 УДК 94(477.85)"1919/1940" UDC DOI: 10.17223/18572685/57/9 БУКОВИНСЬКА МИТРОПОЛІЯ У СКЛАДІ ПОМІСНОЇ РУМУНСЬКОЇ ПРАВОСЛАВНОЇ ЦЕРКВИ (МІЖВОЄННИЙ ПЕРІОД) М.К. Чучко Чернівецький національний університет ім. Ю. Федьковича Україна, 58012, м. Чернівці, вул. Коцюбинського, 2 E-mail: [email protected] Авторське резюме У дослідженні висвітлюється проблема адміністративно-територіального устрою і духовної юрисдикції православної церкви на Буковині в контексті історичних подій, пов’язаних зі зміною державної приналежності цього етноконтактного регіону, який знаходиться на стику східнослов’янського і східнороманського світів. Відзначено, що після включення Буковини до Румунського королівства Буковинська митро- полія увійшла до складу автокефальної Румунської православної церкви та зазнала уніфікації в рамках Румунського патріархату. Незважаючи на негативні явища то- тальної румунізації церковної сфери, у міжвоєнний період спостерігаються також певні позитивні зрушення в житті Буковинської митрополії: будівництво нових храмів, відкриття монастирів, підпорядкування митрополиту Буковинського право- славного релігійного фонду, розвиток духовної освіти. Суттєві корективи в церковне життя православного населення Буковини і Хотинського повіту Бессарабії внесла Друга світова війна, що було пов’язано з евакуацією духовенства з північної частини краю до Румунії в 1940 р. Ключові слова: православна церква, Буковина, етноконтактний регіон, Буковин- ська митрополія, Румунська православна церква, міжвоєнний період. 132 2019. № 57 БУКОВИНСКАЯ -

The Long Way to a Common Easter Date a Catholic and Ecumenical Perspective

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 63(3-4), 353-376. doi: 10.2143/JECS.63.3.2149626 © 2011 by Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. All rights reserved. THE LONG WAY TO A COMMON EASTER DATE A CATHOLIC AND ECUMENICAL PERSPECTIVE BERT GROEN* 1. INTRODUCTION ‘The feast of feasts, the new drink, the famous and holy day…’ With these words and in other poetic language, St. John of Damascus (ca. 650 - before 754) extols Easter in the paschal canon attributed to him.1 The liturgical calendars of both Eastern and Western Christianity commemorate this noted Eastern theologian on December 4. Of course, not only on Easter, but in any celebration of the Eucharist, the paschal mystery is being commemo- rated. The Eucharist is the nucleus of Christian worship. Preferably on the Lord’s Day, the first day of the week, Christians assemble to hear and expe- rience the biblical words of liberation and reconciliation, to partake of the bread and cup of life which have been transformed by the Holy Spirit, to celebrate the body of Christ and to become this body themselves. Hearing and doing the word of God, ritually sharing His gifts and becoming a faith- ful Eucharistic community make the Church spiritually grow. Yet, it is the Easter festival, the feast of the crucified and resurrected Christ par excellence, in which all of this is densely and intensely celebrated. The first Christians were Jews who believed that in Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah had come. Initially, they celebrated the festivals of the Jewish calendar, * Bert Groen is professor of liturgical studies and sacramental theology at the University of Graz, Austria. -

ENGLISH Translation of the Response of the Public Ministry, Prosecutor's

ENGLISH translation of the response of the Public Ministry, Prosecutor’s Office Attached to the High Court of Cassation and Justice (…)By way of the ordinances no. 18/P/2018 of 27.08.2018, 11.09.2018 and 20.09.2018, the Prosecutor’s Office attached to the High Court of Cassation and Justice – Section of Military Prosecutor’s Offices ordered the extension of criminal investigation, continuation of the criminal investigation respectively, against several persons in leadership positions within the General Directorate of Gendarmerie of Bucharest City (DGJMB), the General Inspectorate of Romanian Gendarmerie and the Ministry of Internal Affairs in relation to: - the offense of aiding and abetting, laid down in art. 269 of the Criminal code, consisting in the failure to take measures so that, prior to the execution of the mission of 10th August 2018, in the Piața Victoriei area of Bucharest, all gendarmerie soldiers should wear helmets with identification numbers corresponding to the position they had in the battalion, detachment and intervention group, as well as in drawing up inaccurate official documents, in which no mention was made as to the identity of the soldiers wearing protective helmets the identification numbers of which had been covered with adhesive tape during the intervention in order to prevent or hinder the investigations in the case with regard to the acts of violence exerted during the intervention; - the offense of forgery, laid down in art. 321 of the Criminal code, consisting in the fact that, in the official documents drawn up by the structures of the Romanian Gendarmerie, the data representing the identification numbers assigned by the individual equipment records were knowingly omitted, which made it impossible or difficult to identify the gendarmerie soldiers who committed acts of violence; - the offense of use of false documents, laid down in art. -

The Immoderate and Self-Absorbed Anti-Old Calendarist Zeal of The

D. An Ontological Hallmark of Orthodoxy? HE THIRD of the vehement anti-Old Calendarists, Mr. TAlexandros S. Korakides, concludes his rambling book, Ὀρθοδοξία καὶ Ζωή—Παραπλανήσεις [Orthodoxy and Life: Some Misconceptions]1 with a special chapter of sixteen pages, entitled: “Addendum. The Preposterous Schism of the Last Cen- tury.”2 1. To the attentive reader, it becomes immediately obvious that Mr. Korakides’ language is wholly un-Patristic, because even when dealing with the well-known and truly distress- ing pathology of the Old Calen- darist community, he is abusive and arrogant. 2. Although he holds a doc- torate in theology and has an abundant literary output to his credit (beginning in the 1950s), Mr. Korakides is distinguished, specifically in this text, by a su- percilious and extremely rebar- bative pedantry, which inevita- bly causes him go off the sub- ject, when it comes to both the calendar and ecumenism. 3. Is Mr. Korakides perhaps aiming, by means of an emo- tional, vague, generalizing, confused, and theologically errone- ous exposition, to turn the reader’s attention to his unsubstanti- ated argument, namely, that the entire calendar issue can be re- duced to the failure to accept a “change,” since “changes” have always taken place in the history of the Church?3 I. The Connection Between Ecumenism and the Calendar Question HE UNPARDONABLE sloppiness of Mr. Korakides’ pre- Tsentation, as well as his evident disregard for, or ignorance(?) of, the historical and theological context of the origin and devel- opment of the 1924 reform is fully demonstrated in his conten- tion that the controversy “about ‘ecumenism,’ which has been invented recently and by hindsight” constitutes a “deception of the people of God” and an “invalid and inane pretext.”4 1. -

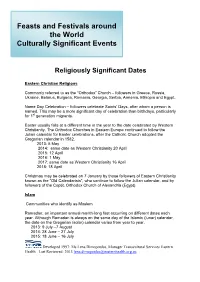

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

The Secretary General's Annual Report 2017

The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2017 The Secretary General’s Annual Report 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .........................................................................................................................................................4 FOR ALL WHO SERVE ........................................................................................................................................8 DETERRENCE, DEFENCE AND DIALOGUE ...................................................................................................10 A Year of Progress .......................................................................................................................................12 Strengthening Collective Defence: An Alliance-wide Response .................................................................13 Safeguarding NATO’s Skies .........................................................................................................................18 Building Resilience .......................................................................................................................................19 Investing in Cyber Defence .........................................................................................................................20 Countering Hybrid Threats ...........................................................................................................................22 Transparency and Risk Reduction ...............................................................................................................23 -

The Life of the Holy Hierarch and Confessor Glicherie of Romania

THE LIFE OF THE HOLY HIERARCH AND CONFESSOR GLICHERIE OF ROMANIA THE LIFE OF THE HOLY HIERARCH AND CONFESSOR GLiCHERIE OF ROMANIA by Metropolitan Vlasie President of the Holy Synod of the True (Old Calendar) Orthodox Church of Romania translated by Sorin Comanescu and Protodeacon Gheorghe Balaban CENTER FOR TRADITIONALIST ORTHODOX STUDIES Etna, California 96027 1999 library of congress catalog card number 99–61475 © 1999 by Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies isbn 0–911165–38–x About the Author The Most Reverend Vlasie, Archbishop and Metropolitan of Romania, is the President of the Holy Synod of the True (Old Calendar) Orthodox Church of Romania, which maintains full li- turgical communion with the True (Old Calendar) Orthodox Church of Greece (Synod of Metropolitan Cyprian), the True (Old Calendar) Orthodox Church of Bulgaria, and the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. His Eminence received his theological education and monas- tic training at the Monastery of the Holy Transfiguration in Slãti- oara, Romania. In 1992, he was awarded the Licentiate in Ortho- dox Theological Studies honoris causa, in recognition of his theo- logical acumen and ecclesiastical accomplishments, by the Directors and Examiners of the Center for Traditionalist Ortho- dox Studies. About the Translators Sorin Comanescu, Romanian by birth, is an architect in North- ern California, where he and his family live. He is a member of the Saint Herman of Alaska Church in Sunnyvale, California, a parish of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. Protodeacon Father Gheorghe Balaban, also Romanian by birth, is assigned to the Saint Herman of Alaska parish. He resides with his wife and family in Palo Alto, California.