The Long Way to a Common Easter Date a Catholic and Ecumenical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clark, Roland. "Reaction." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920S Romania: the Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building

Clark, Roland. "Reaction." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920s Romania: The Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 77–85. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350100985.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 21:07 UTC. Copyright © Roland Clark 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Reaction The process of unifying four different churches into a single patriarchate understandably caused some people to worry that something was being lost in the process. Tensions between metropolitans and bishops reflected dissatisfaction among parish clergy and laypeople as well, which in some cases resulted in the formation of new religious movements. As a society experiencing extraordinary social and political upheavals, including new borders, a nationalizing state, industrialization, new communication and transportation networks and new political ideologies, inter-war Romania was a fecund environment for religious innovation. With monasticism in decline and ever higher expectations being placed on both priests and laypeople, two of the most significant new religious movements of the period emerged in regions where monasticism and the monastic approach to spirituality had been strongest. The first, Inochentism, began in Bessarabia just before the First World War. Its apocalyptic belief that the end times were near included a strong criticism of the Church and the state, a critique that transferred smoothly onto the Romanian state and Orthodox Church once the region became part of Greater Romania. -

Mgr. Nicolai Gennadevich Dubinin

Mgr. Nicolai Gennadevich Dubinin The first catholic bishop with Russian nationality Although few in numbers, Russian Catholics are since Church institutions were re-established present throughout the country, in the following the collapse of communism. He is Archdiocese of the Mother of God at Moscow – auxiliary bishop to the Archdiocese of the which includes the "two capitals" of Moscow and Mother of God in Moscow St Petersburg (separated by 700 kilometres) – The in Novoshakhtinsk born 47-year-old and several other important cities like Pskov, Conventual Franciscan Father Nicolai was part of Kursk, Vladimir and Nizhny Novgorod, all very the very first group of seminarians who attended distant from each other, not to mention the the major seminary after it reopened in Moscow Baltic enclave of Kaliningrad. in 1993. His seminary cohort "recaptured" the Although Catholics currently entertain good Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception through relations with the Russian Orthodox Church and prayers and action, and brought its headquarters Russian authorities, recent bills and government back to the old see in St Petersburg, where it is regulations have complicated the work of foreign currently located. missionaries of all religions in Russia. For In 1995 Dubinin joined the Franciscan conventual example, getting permanent, or at least long- family in Moscow, led at the time by Father term, residence permits is still difficult. Grzegorz Cioroch who taught at the seminary. For the Catholic Church, there are also not Appointed custodian of the Franciscan Province enough local priests to meet the pastoral needs of Russia in 2001, Fr Grzegorz died a few years of the Catholic communities of this vast country; later in a car accident on his way back to Russia the first priests from the St Petersburg Seminary from Poland at the age of 42. -

The True Orthodox Church in Front of the Ecumenism Heresy

† The True Orthodox Church in front of the Ecumenism Heresy Dogmatic and Canonical Issues I. Basic Ecclesiological Principles II. Ecumenism: A Syncretistic Panheresy III. Sergianism: An Adulteration of Canonicity of the Church IV. So-Called Official Orthodoxy V. The True Orthodox Church VI. The Return to True Orthodoxy VII. Towards the Convocation of a Major Synod of the True Orthodox Church † March 2014 A text drawn up by the Churches of the True Orthodox Christians in Greece, Romania and Russian from Abroad 1 † The True Orthodox Church in front of the Ecumenism Heresy Dogmatic and Canonical Issues I. Basic Ecclesiological Principles The True Orthodox Church has, since the preceding twentieth century, been struggling steadfastly in confession against the ecclesiological heresy of ecumenism1 and, as well, not only against the calendar innovation that derived from it, but also more generally against dogmatic syncretism,2 which, inexorably and methodically cultivating at an inter-Christian3 and inter-religious4 level, in sundry ways and in contradiction to the Gospel, the concurrency, commingling, and joint action of Truth and error, Light and darkness, and the Church and heresy, aims at the establishment of a new entity, that is, a community without identity of faith, the so-called body of believers. * * * • In Her struggle to confess the Faith, the True Orthodox Church has applied, and 5 continues to embrace and apply, the following basic principles of Orthodox ecclesiology: 1. The primary criterion for the status of membership in the Church of Christ is the “correct and saving confession of the Faith,” that is, the true, exact and anti innova- tionist Orthodox Faith, and it is “on this rock” (of correct confession) that the Lord 6 has built His Holy Church. -

Generous Orthodoxy - Doing Theology in the Spirit

Generous Orthodoxy - Doing Theology in the Spirit When St Mellitus began back in 2007, a Memorandum of Intent was drawn up outlining the agreement for the new College. It included the following paragraph: “The Bishops and Dean of St Mellitus will ensure that the College provides training that represents a generous Christian orthodoxy and that trains ordinands in such a way that all mainstream traditions of the Church have proper recognition and provision within the training.” That statement reflected a series of conversations that happened at the early stages of the project, and the desire from everyone involved that this new college would try in some measure to break the mould of past theological training. Most of us who had trained at residential colleges in the past had trained in party colleges which did have the benefit of strengthening the identity of the different rich traditions of the church in England but also the disadvantage of often reinforcing unhelpful stereotypes and suspicion of other groups and traditions within the church. I remember discussing how we would describe this new form of association. It was Simon Downham, the vicar of St Paul’s Hammersmith who came up with the idea of calling it a “Generous Orthodoxy”, and so the term was introduced that has become so pivotal to the identity of the College ever since. Of course, Simon was not the first to use the phrase. It was perhaps best known as the title of a book published in 2004 by Brian McLaren, a book which was fairly controversial at the time. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.Long.T65

Cambridge University Press 0521667380 - An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches John Binns Index More information Index Abgar the Black, king of Edessa, 98, 144 Anba Bishoy, monastery, 112 Abraham of Kashkar, 117, 149 Andrassy, Julius, 182 abu ’Ali Mansur al-Hakim, 174 Andreah, Patriarch of Antioch, 219 abu Ja’far al-Mansur, 174 Andrew of Crete, 51, 117 Acacius, Patriarch of Constantinople, 205 Andrew, St, Biblical Theology Institute, Aedesius, of Ethiopia, 145–6 Moscow, 248 Afanas’ev, Nikolai, 42 Andronicus I, Byzantine emperor, 165 Ahmed ibn Ibrahim el-Ghazi or Granj, 34 Anna Comnena, Byzantine empress, 74 Aimilianos, of Simonopetra, 243 Anselm of Canterbury, 206, 209 Akoimetoi, monastery of, 117 Anthimus, Patriarch of Constantinople, 5 Aksentejevi´c,Pavle, 105 Antioch, 1–3, 9, 14–15, 40, 43–4, 143, Alaska, 152, 154–6 148, 203, 207, 220 Albania, Church in, 17, 157, 159 Antonii Khrapovitskii, 25 Alexander, prince of Bulgaria, 183 Antony of Egypt, 108–10, 114, 119 Alexander II, Tsar of Russia, 154 Antony Bloom, Metropolitan of Sourozh, Alexander Paulus, Metropolitan of 234 Estonia, 187 Aphrahat, ‘Persian sage’, 49 Alexandria, 14, 43, 63, 71–2, 115, 144, Aquinas, Thomas, 91 146–7, 158, 169 Arabs, 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 28, 33, 66, 70, 169, Alexis II, Patriarch of Moscow, 105, 238 173, 176, 190, 204; Arab Christianity, Alexius I Comnenus, Byzantine emperor, 15, 55, 79, 146–7, 172 206–7 Armenia, Church in, 30–1, 145, 190, Alexius IV, Byzantine emperor, 207 192, 219 Alexius V, Byzantine emperor, 207 Arseniev, N., 225 al-Harith, 147 Arsenius, -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

Canon Law of Eastern Churches

KB- KBZ Religious Legal Systems KBR-KBX Law of Christian Denominations KBR History of Canon Law KBS Canon Law of Eastern Churches Class here works on Eastern canon law in general, and further, on the law governing the Orthodox Eastern Church, the East Syrian Churches, and the pre- Chalcedonean Churches For canon law of Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with the Holy See of Rome, see KBT Bibliography Including international and national bibliography 3 General bibliography 7 Personal bibliography. Writers on canon law. Canonists (Collective or individual) Periodicals, see KB46-67 (Christian legal periodicals) For periodicals (Collective and general), see BX100 For periodicals of a particular church, see that church in BX, e.g. BX120, Armenian Church For periodicals of the local government of a church, see that church in KBS Annuals. Yearbooks, see BX100 Official gazettes, see the particular church in KBS Official acts. Documents For acts and documents of a particular church, see that church in KBS, e.g. KBS465, Russian Orthodox Church Collections. Compilations. Selections For sources before 1054 (Great Schism), see KBR195+ For sources from ca.1054 on, see KBS270-300 For canonical collections of early councils and synods, both ecumenical/general and provincial, see KBR205+ For document collections of episcopal councils/synods and diocesan councils and synods (Collected and individual), see the church in KBS 30.5 Indexes. Registers. Digests 31 General and comprehensive) Including councils and synods 42 Decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts (Collective) Including related materials For decisions of ecclesiastical tribunals and courts of a particular church, see that church in KBS Encyclopedias. -

The Immoderate and Self-Absorbed Anti-Old Calendarist Zeal of The

D. An Ontological Hallmark of Orthodoxy? HE THIRD of the vehement anti-Old Calendarists, Mr. TAlexandros S. Korakides, concludes his rambling book, Ὀρθοδοξία καὶ Ζωή—Παραπλανήσεις [Orthodoxy and Life: Some Misconceptions]1 with a special chapter of sixteen pages, entitled: “Addendum. The Preposterous Schism of the Last Cen- tury.”2 1. To the attentive reader, it becomes immediately obvious that Mr. Korakides’ language is wholly un-Patristic, because even when dealing with the well-known and truly distress- ing pathology of the Old Calen- darist community, he is abusive and arrogant. 2. Although he holds a doc- torate in theology and has an abundant literary output to his credit (beginning in the 1950s), Mr. Korakides is distinguished, specifically in this text, by a su- percilious and extremely rebar- bative pedantry, which inevita- bly causes him go off the sub- ject, when it comes to both the calendar and ecumenism. 3. Is Mr. Korakides perhaps aiming, by means of an emo- tional, vague, generalizing, confused, and theologically errone- ous exposition, to turn the reader’s attention to his unsubstanti- ated argument, namely, that the entire calendar issue can be re- duced to the failure to accept a “change,” since “changes” have always taken place in the history of the Church?3 I. The Connection Between Ecumenism and the Calendar Question HE UNPARDONABLE sloppiness of Mr. Korakides’ pre- Tsentation, as well as his evident disregard for, or ignorance(?) of, the historical and theological context of the origin and devel- opment of the 1924 reform is fully demonstrated in his conten- tion that the controversy “about ‘ecumenism,’ which has been invented recently and by hindsight” constitutes a “deception of the people of God” and an “invalid and inane pretext.”4 1. -

The Second Church Schism

The Second Church Schism Outline h Review: First Schism h Chalcedonian Orthodox Churches h Second Schism h Eastern Orthodox Churches h Unity Between the 2 Orthodox Families The First Schism h Eutychus’ heresy: > One divine nature (monophysitism) h St. Dioscorus; (St. Cyril’s teachings): > “One nature of God the Word incarnate” (miaphysitism) > “Divine nature and Human nature are united (μία, mia - "one" or "unity") in a compound nature ("physis"), the two being united without separation, without mixture, without confusion, and without alteration.” h Council of Chalcedon (451 A.D.) > Non-Chalcedonian (East): Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch > Chalcedonian (West): Rome and Constantinople Non-Chalcedonian Orthodox Churches h Coptic Orthodox h Syrian Orthodox h Armenian Orthodox h Indian Orthodox h Ethiopian Orthodox h Eritrean Church h All these churches are one family, one in faith, and in the communion of the mysteries. Chalcedonian Orthodox Churches h Group of Churches, which recognize the council of Chalcedon and its canons. >2 Major Sees: Rome, Constantinople >Adopts the formula "in two natures" (dyophysitism) in expressing its faith in the Lord Christ. >Remained united until the eleventh century AD. Chalcedonian Orthodox Churches h They held four additional major councils which they consider ecumenical. >Chalcedonian Orthodox consider seven ecumenical councils as authoritative teaching concerning faith and practice: • Nicea, 325 AD; • Constantinople, 381 AD; • Ephesus, 431 AD; • Chalcedon, 451 AD; • 2nd Constantinople, 553 AD; • 3rd Constantinople, 68O-681 AD; • 2nd Nicea, 787AD. Council in Trullo (Quinisext) in 692 h Held under Byzantine auspices, excluded Rome >Took the practices of the Church of Constantinople as “Orthodox”, condemned Western practices: • using wine unmixed with water for the Eucharist (canon 32), • choosing children of clergy for appointment as clergy (canon 33), • eating eggs and cheese on Saturdays and Sundays of Lent (canon 56) • fasting on Saturdays of Lent (canon 55). -

SEIA NEWSLETTER on the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism

SEIA NEWSLETTER On the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism _______________________________________________________________________________________ Number 182: November 30, 2010 Washington, DC The Feast of Saint Andrew at sues a strong summons to all those who by HIS IS THE ADDRESS GIVEN BY ECU - The Ecumenical Patriarchate God’s grace and through the gift of Baptism MENICAL PATRIARCH BARTHOLO - have accepted that message of salvation to TMEW AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE renew their fidelity to the Apostolic teach- LITURGY COMMEMORATING SAINT S IS TRADITIONAL FOR THE EAST F ing and to become tireless heralds of faith ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30: OF ST. ANDREW , A HOLY SEE in Christ through their words and the wit- Your Eminence, Cardinal Kurt Koch, ADELEGATION , LED BY CARDINAL ness of their lives. with your honorable entourage, KURT KOCH , PRESIDENT OF THE PONTIFI - In modern times, this summons is as representing His Holiness the Bishop of CAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN urgent as ever and it applies to all Chris- senior Rome and our beloved brother in the UNITY , HAS TRAVELLED TO ISTANBUL TO tians. In a world marked by growing inter- Lord, Pope Benedict, and the Church that PARTICIPATE IN THE CELEBRATIONS for the dependence and solidarity, we are called to he leads, saint, patron of the Ecumenical Patriarchate proclaim with renewed conviction the truth It is with great joy that we greet your of Constantinople. Every year the Patriar- of the Gospel and to present the Risen Lord presence at the Thronal Feast of our Most chate sends a delegation to Rome for the as the answer to the deepest questions and Holy Church of Constantinople and express Feast of Sts. -

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

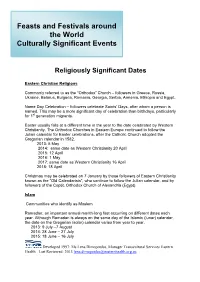

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

The Concept of “Sister Churches” in Catholic-Orthodox Relations Since

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Will T. Cohen Washington, D.C. 2010 The Concept of “Sister Churches” In Catholic-Orthodox Relations since Vatican II Will T. Cohen, Ph.D. Director: Paul McPartlan, D.Phil. Closely associated with Catholic-Orthodox rapprochement in the latter half of the 20 th century was the emergence of the expression “sister churches” used in various ways across the confessional division. Patriarch Athenagoras first employed it in this context in a letter in 1962 to Cardinal Bea of the Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, and soon it had become standard currency in the bilateral dialogue. Yet today the expression is rarely invoked by Catholic or Orthodox officials in their ecclesial communications. As the Polish Catholic theologian Waclaw Hryniewicz was led to say in 2002, “This term…has now fallen into disgrace.” This dissertation traces the rise and fall of the expression “sister churches” in modern Catholic-Orthodox relations and argues for its rehabilitation as a means by which both Catholic West and Orthodox East may avoid certain ecclesiological imbalances toward which each respectively tends in its separation from the other. Catholics who oppose saying that the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church are sisters, or that the church of Rome is one among several patriarchal sister churches, generally fear that if either of those things were true, the unicity of the Church would be compromised and the Roman primacy rendered ineffective.