Inscape 2011 Award Winners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecticut Daily Campus Serving Storrs Since 1396

Connecticut Daily Campus Serving Storrs Since 1396 VOL. LXVIII, NO. 31 CONNECTICUT DAILY CAMPUS FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1963 UCONN COED COLONEL: ASG Constitution Passed; Referendum November 6 Schachter: ''Fight Only Begun'' 1Koinonia'' Seen The Associated Student Govern- Senator Ronald Cassidento, Opportunity For ment Constitution was unanimously chairman of the Finance Commit- ratified by the Student Senate Wed- tee, asked Calder if he had already Self Expression nesday night. received an appropriation from the There were no objections to the Senate to finance the printing of "Koinonia;" the name given to Constitution as a whole. A little the ballots. the Coffee House opened last Sat- discussion proceeded the final vote Calder reported that the com- urday night in the Community as to various amendments concern- mittee had not received any mon- House Auditorium by the U.C.F., ing the Board of Governors, Wo- ey. The reason he proceeded with- is Fellowship. Fellowship is the men"s Student Government, and a out funds was that the ballots were union of individuals expressing few stylistic changes. needed and time was running out. themselves and being heard and When the roll call vote was read Cassidento said to the Senate in being heard and understood as in- there were no absentions and no general that in view of the fact dividuals. negative votes. that the Nutmeg had just run over But how can a Coffee House After ratification President Vic- $5,000 over its budget he could not make fellowship possible in any tor Schachter said. "The battle has allow any monies to be spent by meaningful way? First by simply only just begun." The Constitution the Senate's subsidiary organiza- providing a place to sit and talk has yet to pass a referendum on tions which had not been expressly more private then dorm lounges Nov. -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

An Experiment in Teaching Writing to College Freshmen (Voice Project)

REPORT RESUMES ED 018 112 24 TE 500 064 AN EXPERIMENT IN TEACHING WRITING TO COLLEGE FRESHMEN (VOICE PROJECT). BY- HAWKES, JOHN STANFORD UNIV., CALIF. REPORT NUMBER BR -6 -2075 PUB DATE OCT 67 CONTRACT OEC-4-6062075-1160 EDRS PRICE MF -$1.50 HC- $14.20 353P. DESCRIPTORS-. *COMPOSITION SKILLS (LITERARY), *ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *HIGHER EDUCATION, *COLLEGE FRESHMEN, *TEACHING TECHNIQUES, COMPOSITION (LITERARY), ENGLISH, COURSE CONTENT, WRITING SKILLS, ENGLISH CURRICULUM, READING SKILLS, DISADVANTAGED YOUTH, TAPE RECORDERS, SPEECH, TEACHING METHODS, INSTRUCTIONAL INNOVATION, EXPERIMENTAL TEACHING, LITERATURE, WRITING EXERCISES, STANFORD UNIVERSITY, CALIFORNIA, THIS EXPERIMENT WITH 100 STUDENT VOLUNTEERS WAS CONDUCTED WITHIN THE REGULAR FRESHMAN ENGLISH PROGRAM AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY BY A GROUP OF TEACHERS WHO WERE THEMSELVES WRITERS, AND BY AN EQUAL NUMBER OF GRADUATE STUDENTS. THE AIMS OF THE EXPERIMENT WERE (1) TO TEACH WRITING, NOT THROUGH RHETORICAL TECHNIQUES, BUT THROUGH HELPING THE STUDENT DISCOVER AND DEVELOP HIS OWN WRITING "VOICE" AND A PERSONAL OR IDENTIFIABLE PROSE, WHETHER THE WRITING BE CREATIVE OR EXPOSITORY, (2) TO INVOLVE IN SUCH TEACHING NOVELISTS, POETS, PLAYWRIGHTS, ESSAYISTS, AND PERSONS IN DIVERSE ACADEMIC DISCIPLINES, (3) TO WORK AT VARIOUS AGE LEVELS, THROUGH INVOLVING BOTH STUDENTS AND FACULTY IN EXPERIMENTS IN ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS, (4) TO WORK WITH STUDENTS FROM VARIOUS SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUNDS, AND (5) TO INVOLVE OTHER INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION THROUGH VISITS, EXCHANGES, SEMINARS, AND DEMONSTRATIONS. THE MATERIALS IN THIS REPORT DOCUMENT WHAT WENT ON IN THE CLASSROOM, HOW THE STUDENTS TAUGHT IN LOCAL SCHOOLS, HOW STUDENTS WERE ENCOURAGED TO WRITE AND REVISE THEIR WORK -- ESPECIALLY THROUGH THE USE OF THE TAPE RECORDERS- -AND THE KIND OF TEACHING THAT A GROUP OF STUDENTS UNDERTOOK IN A SPECIAL SUMMER PROGRAM FOR ENTERING NEGRO STUDENTS AT THE COLLEGE OF SAN MATEO. -

2 Records Aug 15 2021

Sept 2, 2021 Latest additions indicated by asterisk (*) C * ? & THE MYSTERIANS 99 TEARS / MIDNIGHT HOUR 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE/CHANNEL SWIMMER 1910 FRUITGUM CO, SIMON SAYS REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 1910 FRUITGUM CO. SIMON SAYS/REFLECTIONS FROM THE LOOKING GLASS 2 R 1910 FRUITGUM CO. INDIAN GIVER / POW WOW 3 SHARPES QUARTET LES MY LOVE WAS NOT TRUE LOVE/BELLE ST. JOHN R 49TH PARALLEL NOW THAT I'M A MAN / TALK TO ME R 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN.... 6 CYLINDER AIN'T NOBODY HERE BUT US CHICKENS / STRONG WOMAN'S LOVE 8TH DAY IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT / IF I COULD SEE THE LIGHT (INST) 9 LAFALCE BROTHERS MARIA, MARIA, MARIA/THE DEVIL'S HIGHWAY A TASTE OF HONEY SUKAYAKI / DON'T YOU LEAD ME ON A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA A*TEENS DANCING QUEEN / MAMMA MIA AARON LEE ONLY HUMAN / EMPTY HEART A * ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU / HAPPY HAWAII A * ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY / CRAZY WORLD ABBOTT GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN / WAIT UNTIL TOMORROW ABBOTT RUSS SPACE INVADERS MEET PURPLE PEOPLE EATER/COUNTRY COOPERMAN ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC ALL OF MY HEART / OVERTURE ABC THAT WAS THEN BUT THIS IS NOW / VERTIGO ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE / THE LOOK OF LOVE ABDUL PAULA MY LOVE IS FOR REAL / SAY I LOVE YOU ABDUL PAULA I DIDN'T SAY I LOVE YOU/MY LOVE IS FOR REAL ABDUL PAULA IT'S JUST THE WAY YOU LOVE ME/DUB MIX . PICTURE SLEEVE ABDUL PAULA THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY/THE PROMISE OF A NEW DAY ABDUL PAULA VIBEOLOGY/VIBEOLOGY ABRAMS MISS MILL VALLEY/THE HAPPIEST DAY OF MY LIFE ABRAMSON RONNEY NEVER SEEM TO GET ALONG WITHOUT YOU/TIME -

Koerner 1 and WHAT WE SAW THERE

Koerner 1 DEFINING A MICRO-GENRE: INSULAR FRIEND GROUPS IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE and WHAT WE SAW THERE: A NOVEL ________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Honors Tutorial College Ohio University ________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the Degree of Bachelors of Arts in English ________________________________________________ Hannah Koerner April 2017 Koerner 2 Critical Introduction Defining a Micro-Genre: Insular Friend Groups in Contemporary Literature Three tall, gray bookshelves line the back wall of my parents’ office at home. They are filled with historical fiction, Joan Didion collections, and tall, wide books of nature photography. They have been there as long as I can remember, but I only started reading books from them when I was in high school. It was in my sophomore year, after finishing off the Alice Hoffman novels and Erik Larson’s nonfiction that I stumbled upon Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. It is an immediately arresting cover: a close-up of a Greek statue’s face and neck, turned to the side, mouth slightly opened and downturned as if looking away from something terrible and regretful—something tragic. The photograph is faded and warm, almost sepia-toned, like something you might find while perusing bins in an antique store. It’s a fitting cover; The Secret History is a tragedy, and like all tragedies, it owes a deep debt to the past. When I finally read and finished the book, it was the tragedy that held me—not because it was classical and well-crafted (it was both), but because of the unfairness. -

Streamline: Slacker Country Gale, Owen in Good Company

January 9, 2017, Issue 532 Gale, Owen In Good Company “It was unbelievably short notice and very flattering.” That’sJake Owen’s new manager Keith Gale on their partnership in Good Company Entertainment (CAT 1/5). Gale has been integral to Owen’s career from the outset. “I guess I’ve been a de-facto advisor for years, but for the life of me I never saw this coming,” he says. Owen parted ways with Morris Higham Management before the holidays. Says Gale, “Out of nowhere he said, ‘Why don’t you be my manager?’ I went, ‘Come again?’” Ultimately, he and Owen share a singular focus and vision that goes back more than a decade. “I’ve had 13 great years with Dale Morris and that team,” Owen tells Country Aircheck. “I wouldn’t be where I am with- out them, but it was time to make a change. Keith has been in- volved since day one and we’ve formed not only a great working relationship but a great friendship. He understands me and the vision I have for my career. There was no doubt in my mind he was the right guy. And I’m flattered he wanted to partner with me. At this point, it’s all I could ask for – to have a team that wakes up every day and I’m their only concern.” There Is No Try: BMLG Records’ Ryan Follese asks WWKA/ Right On Time: Nevertheless, Orlando’s Drew Bland for the conversion. Owen admits to some trepidation. “It was tricky considering he did such a great job at Sony and there are so Streamline: Slacker Country many artists relying on him to make Music streaming service Slacker Radio is mixing the old their careers blossom. -

J2P and P2J Ver 1

SEPTEMBER 14, 1963 SIXTY -NINTH YEAR 50 CENTS PETE SEEGER NIXES OATH; ABC BAN STAYS NEW YORK -ABC Television, which has up till now refused to let outstanding folk singer Pete Seeger appear on the network's weekly "Hootenanny," asked him last week to sign a "loyalty oath affidavit" as a prerequisite for going on the show. Seeger refused. Harold Leventhal, Seeger's manager, accused the network of continuing a blacklisting policy against Seeger and other singers, including the Weavers, whom he also manages. BïlPwa ABC, in effect, admitted that Seeger's political leanings were The International Music -Record Newsweekly behind its refusal to put him on. A network statement confirmed that ABC had sent word to Seeger it would "consider" using him if rn inikitingirTapiagainkiatCoin Machine Operating (Continued on page 6) Coinmen Hold Despite Threat of Bill ,\ Chi Convention Senate Group r Mercury Flies High on Fall Plan' By REN GREVAIT Affirms MOA To Look Into NEW YORK-Mercury Records last week NEW YORK-Mercury execs, in a series of unveiled a special fall plan, "Rally 'Round the high -flying jet flights, covered close to 6,000 Stars," key plank of which is a 10 per cent miles last week in holding three separate sales discount for the next 45 days on new releases meetings, spanning both coasts in five days. Healthy Future SESAC Battle and catalog product. Tradesters were inclined Three regional conventions were held in New (5); (6), Los (9). to call the Mercury program "conservative," and York Chicago and Angeles By AARON STERNFIELD WASHINGTON - SESAC's in line with what appeared in many circles to be Attending all the sessions, which were keyed battle with Southern broadcast- a gradual "firming up" of manufacturer sales to a political convention theme, were President CHICAGO -The Music Op- ers who accuse the licensing policies. -

Philips Records Discography

Philips Records Discography 200-000 series PHM 200-000/PHS 600-000 - Broadway Is My Beat - MICHEL LEGRAND [1962] A Wonderful Guy/Bewitched/I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’/If I Loved You/Make Believe/Oh What A Beautiful Mornin’/Old Devil Moon/On The Street Where You Live/Smoke Gets In Your Eyes/Summertime/The Surrey With The Fringe On Top/Yesterdays [*] PHM 200-001/PHS 600-001 - French Horns For My Lady - JULIUS WATKINS [1962] Temptation/Clair De Lune/September Song/Catana/I’m A Fool To Want You//Speak Low/Nuages/The Boy Next Door/Mood Indigo/Home (When Shadows Fall) PHM 200-002/PHS 600-002 - Skinnay Ennis Salutes Hal Kemp - SKINNAY ENNIS [1962] A Foggy Day/Cheek To Cheek/Got A Date With An Angel (Skinnay Ennis Theme)/(How I’ll Miss You) When Summer Is Gone (Hal Kemp Theme)/I’m Breathless/I’ve Got You Under My Skin/Love For Sale/Rhythm Is Our Business/Scatter-Brain/When Did You Leave Heaven/Whispers In The Dark/You’ve Got Me Crying Again [*] PHM 200-003/PHS 600-003 - Golden Bluegrass Hits - The BARRIER BROTHERS [1962] Blue Moon Of Kentucky/Gotta Travel On/Polka On A Banjo/Cryin’ My Heart All Over You/My Little Georgia Rose/Salty Dog Blues//Earl’s Breakdown/Cabin On The Hill/Flint Hill Special/Stonewall Around Me/Before I Met You/Breakin’ In A Brand New Pair Of Shoes PHM 200-004/PHS 600-004 - Swing Low, Sweet Clarinet - The WOODY HERMAN QUARTET [1962] Alexandra/Begin The Beguine/Blue Moon/Don’t Be That Way/Mood Indigo/On The Sunny Side Of The Street/Pee Wee Blues/Rose Room/Someday Sweethear/Summit Ridge Drive/Sweet Lorraine/Swing Low, Sweet Clarinet [*] PHM 200-005/PHS 600-005 - Dual Pianos-World Favorite Piano Classics - RAWICZ & LANDAUER [1962] PHM 200-006/PHS 600-006 - Singin’ Happy - FRANKIE VAUGHAN [1962] PHM 200-007/PHS 600-007 - The Explosive! Freddy Cannon - FREDDY CANNON [1962] (reissue of Swan SLP 502) Boston (My Home Town)/Kansas City/Sweet Georgia Brown/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/St. -

Diamond Line Undergraduate Literary Magazine

Diamond Line Undergraduate Literary Magazine Volume 1 Issue 3 Article 1 April 2021 Diamond Line - Spring 2021 Diamond Line Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/diamondlinelitmag Recommended Citation Editors, Diamond Line (2021) "Diamond Line - Spring 2021," Diamond Line Undergraduate Literary Magazine: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/diamondlinelitmag/vol1/iss3/1 This Entire Issue is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diamond Line Undergraduate Literary Magazine by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIAMOND LINE AN UNDErgrADUATE LITERARY MAGAZINE SPRING 2021 ISPRING 2021 SSISSUEUE NNOO. .33 The Diamond Line ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS MASTHEAD Issue 3 Special thanks to: DITORIAL TAFF RODUCTION TAFF May 2021 J. William Fulbright College of Arts & Sciences at the University of Arkansas E S P S The University of Arkansas Department of English EDITOR-IN-CHIEF DESIGN EDITOR (PRINT) The University of Arkansas Program in Creative Writing and Translation Bridgid O’Kane Camilla Shumaker Bridgid O’Kane Sophia Milligan ANAGING DITOR And all the undergraduate faculty who encourged their students to submit M E DESIGN EDITORIAL TEAM (PRINT) their work, and the student writers who contributed, without whom Heather Drouse Heather Drouse The Diamond Line would not be possible. Destiny Eberhard FICTION EDITOR Jada Fields Kara Hutchinson SUBMISSIONS Kara Hutchinson Kate Schlie The Diamond Line accepts: Poetry FICTION EDITORIAL TEAM DESIGN EDITOR (WEB) Flash/Fiction Eruby Rodriguez Creative Nonfiction Amelia Bushek Destiny Eberhard Drama DESIGN EDITORIAL TEAM (WEB) Photography POETRY EDITOR Paintings/Drawings/Illustrations/Sequential Art Amelia Bushek Sculpture Danika Sanders Courtney Demmitt Danika Sanders The Diamond Line only accepts pieces by undergraduates at the POERY EDITORIAL TEAM Fuschia Muckley University of Arkansas. -

KING of AMERICA by CURTIS RUTHERFORD a THESIS

KING OF AMERICA by CURTIS RUTHERFORD A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of the Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2011 Copyright Curtis Rutherford 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This is a collection of poetry and prose by Curtis Rutherford. The majority of this manuscript was written between April 2010 and February 2011. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Soviet space dog, Laika (c. 1954-1957). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Owen Wister Review: ―My Sparkler Bomb‖ Phi Kappa Phi Forum: ―Mustangs‖ Steel Toe Review: ―Holy‖ Catch Up: ―Softball‖ and ―Drip Drip‖ My gratitude to the teachers, editors and friends who contributed to the completion of this manuscript—Sheila Black, Joel Brouwer, Barbara Chotiner, Terrance Hayes, Katya Iakubenko, Danny Letz, Dave Madden, Sergey Parizhskiy, Peter Streckfus, Roxana Tuleneva, Connie Voisine and Kathleene West. I wish to offer a special thank you to Robin Behn for her energy, encouragement and invaluable guidance. iv CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...…….…ii DEDICATION…………………………………………………………...…………….…………iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………....…....iv My Sparkler Bomb………………………………………………………………………………..1 Your Energy In Memphis………………………………………………………………………....3 Mustangs……………………………………………………………………………………..……4 March to the Sea.……….……………………………………………………………………....…5 Diagnostics……………………………………………………………………………..……….....6 The Missionaries Come to Finish What they Started……………………………………….….…7 -

Candida (1897)

1 George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) Candida (1897) George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) was an Irish playwright who espoused the ideals of the realist theater of Ibsen. He won the Nobel prize in Literature in 1925. He wrote many plays that are still performed today, including Arms and the Man (1894), Cesar and Cleopatra (1898), Pygmalion (1912), later made into the movie My Fair Lady, and Saint Joan (1923). Candida was written in 1894. Act I A fine October morning in the north east suburbs of London, a vast district many miles away from the London of Mayfair and St. James's, much less known there than the Paris of the Rue de Rivoli and the Champs Elysees, and much less narrow, squalid, fetid and airless in its slums; strong in comfortable, prosperous middle class life; wide-streeted, myriad-populated; well- served with ugly iron urinals, Radical clubs, tram lines, and a perpetual stream of yellow cars; enjoying in its main thoroughfares the luxury of grass-grown "front gardens," untrodden by the foot of man save as to the path from the gate to the hall door; but blighted by an intolerable monotony of miles and miles of graceless, characterless brick houses, black iron railings, stony pavements, slaty roofs, and respectably ill dressed or disreputably poorly dressed people, quite accustomed to the place, and mostly plodding about somebody else's work, which they would not do if they themselves could help it. The little energy and eagerness that crop up show themselves in cockney cupidity and business "push." Even the policemen and the chapels are not infrequent enough to break the monotony. -

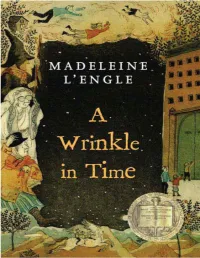

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'engle

A Wrinkle in Time OTHER NOVELS IN THE TIME QUINTET An Acceptable Time Many Waters A Swiftly Tilting Planet A Wind in the Door A Wrinkle in Time MADELEINE L’ENGLE FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX Square Fish An Imprint of Holtzbrinck Publishers A WRINKLE IN TIME. Copyright © 1962 by Crosswicks, Ltd. An Appreciation Copyright © 2007 by Anna Quindlen. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Square Fish, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data L’Engle, Madeleine. A wrinkle in time. p. cm. Summary: Meg Murry and her friends become involved with unearthly strangers and a search for Meg’s father, who has disappeared while engaged in secret work for the government. ISBN-13: 978-0-312-36755-8 ISBN-10: 0-312-36755-4 [1. Science fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.L5385 Wr 1962 62-7203 Originally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux Book design by Jennifer Browne First Square Fish Mass Market Edition: May 2007 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Charles Wadsworth Camp and Wallace Collin Franklin Contents An Appreciation by Anna Quindlen 1 Mrs Whatsit 2 Mrs Who 3 Mrs Which 4 The Black Thing 5 The Tesseract 6 The Happy Medium 7 The Man with Red Eyes 8 The Transparent Column 9 IT 10 Absolute Zero 11 Aunt Beast 12 The Foolish and the Weak Go Fish: Questions for the Author Newbery Medal Acceptance Speech: The Expanding Universe An Appreciation BY ANNA QUINDLEN The most memorable books from our childhoods are those that make us feel less alone, convince us that our own foibles and quirks are both as individual as a finger-print and as universal as an open hand.