How the Young Use Twitter to Challenge Thailand's Most

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

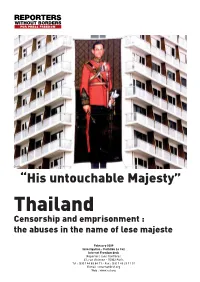

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the Publication of the White Paper on Surrogacy in 2015, There Have Been Addit

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the publication of the white paper on surrogacy in 2015, there have been additional cases of concern as well as some legal developments. While surrogacy has become increasingly lauded due to its use by celebrities, its troubling aspects continue to receive short shrift in media and culture. This addendum to that paper provides some updates and examples related to laws, cases, and surrogacy stories which have emerged that raise highlight the risks and problems associated with the practice. Examples of changes in laws related to surrogacy Due to concerns about surrogacy tourism and exploitation, India took steps to limit its surrogacy industry in 2018. The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2016 banned commercial surrogacy and prohibited foreigners from contracting with surrogates.1 Under the law’s provisions, surrogates must be a close relative and may only be reimbursed for medical expenses, in hopes of ensuring that vulnerable poor women are not exploited.2 The law also restricted altruistic surrogacy to infertile, married heterosexual couples.3 As of 2020, the legislature was considering some changes to the law based on recommendations from a committee, such as allowing divorced or widowed women access to surrogacy, removing the requirement that a surrogate be a close relative, and removing the five year infertility requirement.4 Turkey had already prohibited surrogacy, but has sought to strengthen its rules, including criminal penalties. A 2017 report noted that the Health Ministry proposed -

Laos in 2002: Regime Maintenance Through Political Stability

LAOS IN 2002 Regime Maintenance through Political Stability Carlyle A. Thayer Abstract In 2002, Laos emerged from a period of economic turbulence and political insecurity. The econ- omy showed signs of recovery from the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis. But economists noted some worrying long-term trends. Foreign donors demonstrated their confidence by continuing to provide development assistance. Domestic insurgency appeared on the decline. In February, Laos conducted trouble-free national elections. The Lao government also made some positive adjustments in its treatment of Christian minority groups. Externally, Laos gave priority to rein- forcing relations with its immediate neighbors, Vietnam, Thailand, and China. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (LPDR) is one of the world’s least-developed countries and one of the last remaining socialist states in Asia. During 2002 the one-party regime continued to consolidate its hold on power. Domestic insurgency fell and there was no renewal of the urban bombing attacks that struck Laos in 2000–01. The Lao economy continued to recover from the aftershocks of the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis, although serious structural problems remained. No serious problems emerged in Laos’s external relations. Bilateral relations with Vietnam were further strengthened. Political Stability On February 24, 2002, Laos held elections for the Na- tional Assembly. The ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP) ap- proved a slate of 166 candidates to contest 109 seats, an increase of 10 from the previous legislature. The average age of candidates dropped by 10 years to 51. Twenty percent of the candidates were women and 34% were univer- sity graduates, an increase in both categories. -

Realpolitik and Resistance - the Birth Pangs of Timor Loro Sa’E

Lund University Master’s Thesis Department of Sociology May 2001 Master’s Programme in East and Supervisor: Gudmund Jannisa Southeast Asian Studies Realpolitik and Resistance - The Birth Pangs of Timor Loro Sa’e - “Peace? Why would we want peace? If the vote is for independence we’ll just kill; kill everybody” Filomeno Orai, Leader of the FPDK ( pro-Jakarta) militia, East Timor, September 1999. Joel Andersson 1 Lund University Master Programme of East and Southeast Asian Studies Masters Thesis Department of Sociology Autumn 2000 Supervisor: Gudmund Jannisa, Kristianstad University Realpolitik and Resistance- The Birth Pangs of Timor Loro Sa’e by Joel Andersson Abstract During the turbulent times surrounding the independence of East Timor the writer of this thesis was working in Jakarta with the United Nations High Commissioner for refugees. It was in this position the writer got the idea to study the transformation of East Timor from an occupied territory within the Republic of Indonesia to an independent state, and what the main reasons were for this change to take place. The thesis starts off by explaining East Timor’s historic setting. The thesis continues by looking into the actions and policies of the big political actors such as United States of America, Australian and the UN. This is followed by a close look on the role of the East Timorese people in general and some of the leaders such as Xanana Gusmao and Jose Ramos Horta in particular. When examining the relationship between the international communities, the independence movement and its leaders the writer uses theories developed by Ron Eyerman and Andrew Jamison in their study “Social Movements – a Cognitive Approach”. -

Criminal Defamation: Still “An Instrument of Destruction” in the Age of Fake News

CRIMINAL DEFAMATION: STILL “AN INSTRUMENT OF DESTRUCTION” IN THE AGE OF FAKE NEWS Jane E. Kirtley* & Casey Carmody** I. INTRODUCTION When Bangladeshi journalist Abdul Latif Morol, a correspondent for the Daily Probaha, used Facebook on August 1, 2017 to relay reports about the death of a goat, he was not expecting to be the target of a criminal defamation prosecution.1 The previous day, Bangladesh’s Minister of State for Fisheries and Livestock Narayan Chandra Chanda donated the goat to a poor farmer in Dumuria during an event sponsored by the government’s local livestock department.2 Following the event, news organizations published stories noting that the goat had died overnight. Morol took to Facebook to report the information, writing, “Goat given by state minister in the morning dies in the evening.”3 Soon after the post was published, fellow journalist Subrata Faujdar, a correspondent for the Daily Spandan, filed a criminal defamation complaint against Morol.4 Faujdar claimed that Morol’s post, which also contained a photo of the minister, was intended to demean the official.5 Faujdar was a supporter of the ruling party in Bangladesh and filed the complaint because * Silha Professor of Media Ethics and Law, and Director, Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law, Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Minnesota; Affiliated Faculty Member, University of Minnesota Law School. ** PhD Candidate, Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Minnesota. The authors gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Scott Memmel, PhD candidate and editor Silha Bulletin, Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Minnesota, in the preparation of this article. -

The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2020

THE DEATH PENALTY FOR DRUG OFFENCES: GLOBAL OVERVIEW 2020 The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Harm Reduction International (HRI) is a leading Global Overview 2020 non-governmental organisation dedicated to Ajeng Larasati and Giada Girelli reducing the negative health, social and legal © Harm Reduction International, 2021 ISBN 978-1-8380910-6-4 impacts of drug use and drug policy. We promote the rights of people who use drugs and their Designed by ESCOLA Published by communities through research and advocacy to Harm Reduction International help achieve a world where drug policies and laws 61 Mansell Street, Aldgate contribute to healthier, safer societies. London E1 8AN Telephone: +44 (0)20 7324 3535 E-mail: [email protected] The organisation is an NGO with Special Website: www.hri.global Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. Acknowledgements This report would not be possible without data made available or shared by human rights organisations and individual experts, many of which provided advice and assistance throughout the drafting process. We would specifically like to thank the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN), the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR), Hands Off Cain, the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR), Justice Project Pakistan, LBH Masyarakat, Odhikar, Project 39A (National Law University, Delhi), Reprieve and The Rights Practice. We are also indebted to Iyad Alqaisi, Fahri Azzat, Ricky Gunawan, Pulasthi Hewamanna, Carolyn Hoyle, Richard Lines, M. Ravi and Tripti Tandon. Thanks are also owed to colleagues at Harm Reduction International for their feedback and support in preparing this report: Gen Sander, Cinzia Brentari, Naomi Burke-Shyne, Catherine Cook, Robert Csák, Colleen Daniels, Lucy O’Hare, Maddie O’Hare, Suchitra Rajagopalan, Emily Rowe, Sam Shirley-Beavan, Olga Szubert and Anne Taiwo. -

Laos in 2013: Macroeconomic Ambitions, Human-Centered Shortcomings Author(S): Brendan M

Laos in 2013: Macroeconomic Ambitions, Human-centered Shortcomings Author(s): Brendan M. Howe Source: Asian Survey, Vol. 54, No. 1, A Survey of Asia in 2013 (January/February 2014), pp. 78-82 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/as.2014.54.1.78 . Accessed: 29/07/2014 00:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asian Survey. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.56.91.178 on Tue, 29 Jul 2014 00:26:44 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BRENDAN M. HOWE Laos in 2013 Macroeconomic Ambitions, Human-centered Shortcomings ABSTRACT In 2013 Laos joined the World Trade Organization, economic growth was over 8%, and graduation from least-developed country status by 2020 remains achievable. But its human development index of 0.543 remained below the regional average. Macro development projects still threaten the vulnerable. The abduction of a prominent campaigner and repatriation of North Korean refugees highlighted human rights challenges. KEYWORDS: Laos, development, human rights, human security INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS Laos informed the World Trade Organization (WTO) on January 3, 2013, that it had ratified its membership agreement, becoming the organization’s 158th member on February 2, after 15 years of effort. -

Jadeand Conflict

JADE AND CONFLICT Myanmar’s Vicious Circle June 2021 2 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS / MAIN ARMED ORGANISATIONS ACTIVE IN THE JADE SECTOR .................. 4 MAP OF MYANMAR ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. JADE AND CONFLICT: MYANMAR’S VICIOUS CIRCLE ...................................................................... 10 1.1 The NLD attempts to break the jade-conflict nexus ..................................................................................... 10 1.2 Mining reform derailed .................................................................................................................................. 11 Case Study: The 2019 Gemstone Law ........................................................................................................... 12 Case Study: State watchdog MGE keeps cosy industry ties rife with conflicts of interest .......................... 18 1.3 Jade after the coup ........................................................................................................................................ 22 2. ARMED GROUPS HOOKED ON JADE REVENUES .............................................................................. 26 2.1 The Tatmadaw profits from control over mining ........................................................................................ -

Natalie Condon Fragmentary Sexuality: The

Natalie Condon Fragmentary Sexuality: the Transnational Gestational Surrogacy Market in Thailand and the Nationalist “Baby Gammy” Scandal Using Emily Martin's 1987 ethnographic analysis of female bodies in biomedical settings, this paper investigates the illegal transnational gestational surrogacy market based in Thailand by examining nationalist and gendered rhetoric found on Thai surrogacy clinic websites and in the international media coverage of the "Baby Gammy" scandal of 2014. “The main objective of this agency is to make your ‘Surrogacy Journey’ hassle-free, emotionally rewarding, and financially viable,” reads the description on the homepage of Bangkok Surrogacy, one of Thailand’s most successful surrogacy agencies. “We offer a one-stop-shop solution for starting from surrogate matching service to legal assistance to all Intended Parents” (Bangkok Surrogacy 2016). In this paper I analyze the emergent “Surrogacy Journey” of the transnational gestational surrogacy industry of 21st century Thailand, an overlapping network of Thai surrogate mothers, typically Australian, American, or Israeli commissioning parents, online gamete donors, foreign-owned surrogacy agencies, and illegal clinics concealed in Bangkok’s streets. Working from Marilyn Strathern’s analysis of reproductive technologies (1995: 355), I locate sexuality in a technological process of separation unique to transnational gestational surrogacy. Drawing on work from anthropologists Andrea Whittaker and Emily Martin, I argue that surrogates’ are involved in complex processes