The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Propaganda in Mexico's Drug War (2012)

PROPAGANDA IN MEXICO’S DRUG WAR America Y. Guevara Master of Science in Intelligence and National Security Studies INSS 5390 December 10, 2012 1 Propaganda has an extensive history of invisibly infiltrating society through influence and manipulation in order to satisfy the originator’s intent. It has the potential long-term power to alter values, beliefs, behavior, and group norms by presenting a biased ideology and reinforcing this idea through repetition: over time discrediting all other incongruent ideologies. The originator uses this form of biased communication to influence the target audience through emotion. Propaganda is neutrally defined as a systematic form of purposeful persuasion that attempts to influence the emotions, attitudes, opinions, and actions of specified target audiences for ideological, political or commercial purposes through the controlled transmission of one-sided messages (which may or may not be factual) via mass and direct media channels.1 The most used mediums of propaganda are leaflets, television, and posters. Historical uses of propaganda have influenced political or religious schemas. The trend has recently shifted to include the use of propaganda for the benefit of criminal agendas. Mexico is the prime example of this phenomenon. Criminal drug trafficking entities have felt the need to incite societal change to suit their self-interest by using the tool of propaganda. In this study, drug cartel propaganda is defined as any deliberate Mexican drug cartel act meant to influence or manipulate the general public, rivaling drug cartels and Mexican government. Background Since December 11, 2006, Mexico has suffered an internal war, between quarreling cartels disputing territorial strongholds claiming the lives of approximately between 50,000 and 100,000 people, death estimates depending on source.2 The massive display of violence has strongly been attributed to President Felipe Calderon’s aggressive drug cartel dismantling policies and operatives. -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

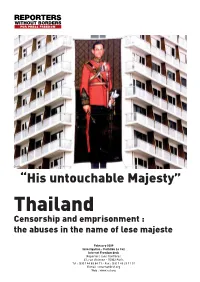

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

Explaining the Slight Uptick in Violence in Tijuana

JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY EXPLAINING THE SLIGHT UPTICK IN VIOLENCE IN TIJUANA BY NATHAN P. JONES, PH.D. ALFRED C. GLASSELL III POSTDOCTORAL FELLOW IN DRUG POLICY JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 17, 2013 Explaining the Slight Uptick in Violence in Tijuana THESE PAPERS WERE WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN A BAKER INSTITUTE RESEARCH PROJECT. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THESE PAPERS ARE REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE THEY ARE RELEASED. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THESE PAPERS ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S), AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. © 2013 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. 2 Explaining the Slight Uptick in Violence in Tijuana Introduction After a two-year decline in drug-related violence in Tijuana, seven homicides were reported in a two-day period in early June 2013.1 The homicides are notable because Tijuana is one of the few places in Mexico where drug violence has spiked and subsequently subsided. This white paper explores the reasons behind the limited increase in violence and provides policy recommendations to address it. Between 2008-2010, drug-related violence between two factions of the Arellano Felix cartel nearly brought Tijuana to its knees.2 However, the 2010 arrest of a top cartel lieutenant brought relative peace to the city, prompting the administration of former Mexico president Felipe Calderón to promote Tijuana as a public safety success story. -

A Massacre in Jamaica

A REPORTER AT LARGE A MASSACRE IN JAMAICA After the United States demanded the extradition of a drug lord, a bloodletting ensued. BY MATTATHIAS SCHWARTZ ost cemeteries replace the illusion were preparing for war with the Jamai- told a friend who was worried about an of life’s permanence with another can state. invasion, “Tivoli is the baddest place in illusion:M the permanence of a name On Sunday, May 23rd, the Jamaican the whole wide world.” carved in stone. Not so May Pen Ceme- police asked every radio and TV station in tery, in Kingston, Jamaica, where bodies the capital to broadcast a warning that n Monday, May 24th, Hinds woke are buried on top of bodies, weeds grow said, in part, “The security forces are ap- to the sound of sporadic gunfire. over the old markers, and time humbles pealing to the law-abiding citizens of FreemanO was gone. Hinds anxiously di- even a rich man’s grave. The most for- Tivoli Gardens and Denham Town who alled his cell phone and reached him at saken burial places lie at the end of a dirt wish to leave those communities to do so.” the house of a friend named Hugh Scully, path that follows a fetid gully across two The police sent buses to the edge of the who lived nearby. Freeman was calm, and bridges and through an open meadow, neighborhood to evacuate residents to Hinds, who had not been outside for far enough south to hear the white noise temporary accommodations. But only a three days, assumed that it was safe to go coming off the harbor and the highway. -

Pablo Escobar: Drug Lord As Heroic Archetype Adem Ahmed Bucknell University, [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2016 Pablo Escobar: Drug Lord as Heroic Archetype Adem Ahmed Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Ahmed, Adem, "Pablo Escobar: Drug Lord as Heroic Archetype" (2016). Honors Theses. 344. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/344 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PABLO ESCOBAR Drug Lord as Heroic Archetype by Adem Ahmed Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors In Comparative Humanities April 1, 2016 Approved by: ________________________ Adviser: James Mark Shields ________________________ Co-Adviser: David Rojas _______________________ Department Chair: Katherine Faull 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor James Shields, both my academic and primary thesis advisor. His patience, dedication and continual support in my endeavors have played a large role in my accomplishments. I would like to thank Professor David Rojas, who courteously agreed to serve as my co- advisor. As a native Colombian, without his expertise I would not have been able to complete this thesis. I also find it appropriate to thank Professor Slava Yastremski, who served as my advisor for as long as he could. Lastly, I would like to thank my family for their continuous support in both my personal and academic success. My gratitude towards them cannot be expressed in words. -

Combating Illicit Drug Trafficking by Undercover Operations by Mr

COMBATING ILLICIT DRUG TRAFFICKING BY UNDERCOVER OPERATIONS Wasawat Chawalitthamrong* I. INTRODUCTION Drug crime is a major problem facing every society in the world at present. They are different from the past by having secretly specialized and complicated systems. New technology techniques are used as tools, and drug crime is committed in systematic ways and in networks which involve organized crime and transnational crime, causing severe damage and effects on society, economics, politics and national security. Investigation cannot lead to offenders so efficient special investigation is needed to be used for wiretapping, intercepts, undercover operations, and controlled delivery. Special investigation plays a very important role in suppressing and convicting offenders. To understand how to handle organized crime and drug dealers, the comprehension of laws, investigation systems and techniques of drug crime investigation are necessary. Moreover, creating networks for information exchange and joint investigation will be the permanent solution and drug crime prevention. II. CHAPTER ONE A. Investigation Principles and Techniques of Drug Crime Investigation Drug crime is different from other crimes since it is committed by a group of people engaged in organized crime and by secretly specialized and complicated systems. Normal investigation cannot lead to a drug lord. The drug lord always avoids prosecution and conviction due to the lackof evidence such as drugs and money from drug dealings, except for money from money laundering. Collecting evidence and judicial proceedings with offenders need effective investigative techniques that are different form general crime suppression. To operate systematically and efficiently, undercover operations are the best solution for drug crime and for obtaining justice. -

Understanding the Sinaloa Cartel Like a Corporation to Reduce Violence in Mexico

SINALOA INCORPORATED: UNDERSTANDING THE SINALOA CARTEL LIKE A CORPORATION TO REDUCE VIOLENCE IN MEXICO The University of Texas at Austin – B.A. Adriana Ortiz (TC 660H or TC 359T) Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin August 14, 2017 __________________________________________ (Supervisor Name) (Supervisor Department) Supervising Professor __________________________________________ (Second Reader Name) (Second Reader Department) Second Reader Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Stephanie Holmsten and Dr. Rachel Wellhausen for their support, patience, and guidance over the course of this project. Secondly, I want to thank my family and friends for offering me the strength to continue writing even when I hit roadblocks or was extremely stressed out. Lastly, I want to thank the Plan II Office thesis advisors and academic advisors for their continued support and belief that I could finish the project. ~ 2 ~ Abstract Author: Adriana M Ortiz Title: Sinaloa Incorporated: Understanding the Sinaloa Cartel like a Corporation to Reduce Violence in Mexico Supervising Professor: Dr. Stephanie Holmsten Second Reader: Dr. Rachel Wellhausen The Sinaloa Cartel is one of the various drug cartels currently existing in Mexico, but unlike other drug cartels, the Sinaloa Cartel has lasted the longest, was titled the most powerful drug cartel in the world by the U.S. Treasury Department and developed the most sophisticated business system. The characteristics of the system are strategies that legal corporations such as the United Fruit Company, the Brown and Williamson Company, and the Browning Arms Company use; and that includes offshoring, social media, and collaboration with the government of its home state, respectively. -

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the Publication of the White Paper on Surrogacy in 2015, There Have Been Addit

Surrogacy White Paper Addendum: 2020 Update Since the publication of the white paper on surrogacy in 2015, there have been additional cases of concern as well as some legal developments. While surrogacy has become increasingly lauded due to its use by celebrities, its troubling aspects continue to receive short shrift in media and culture. This addendum to that paper provides some updates and examples related to laws, cases, and surrogacy stories which have emerged that raise highlight the risks and problems associated with the practice. Examples of changes in laws related to surrogacy Due to concerns about surrogacy tourism and exploitation, India took steps to limit its surrogacy industry in 2018. The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill 2016 banned commercial surrogacy and prohibited foreigners from contracting with surrogates.1 Under the law’s provisions, surrogates must be a close relative and may only be reimbursed for medical expenses, in hopes of ensuring that vulnerable poor women are not exploited.2 The law also restricted altruistic surrogacy to infertile, married heterosexual couples.3 As of 2020, the legislature was considering some changes to the law based on recommendations from a committee, such as allowing divorced or widowed women access to surrogacy, removing the requirement that a surrogate be a close relative, and removing the five year infertility requirement.4 Turkey had already prohibited surrogacy, but has sought to strengthen its rules, including criminal penalties. A 2017 report noted that the Health Ministry proposed