Copyright by Marian Jean Barber 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of the Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin

“Our Heritage, Our Treasure”: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of the Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin Emily J. Herkert History 489: Capstone November 2015 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by the McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...iii Lists of Figures and Maps………………………………………………………………………...iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Background………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Historiography…………………………………………………………………………………….8 The Construction of the Lidice Memorial……………………………………………………….13 Memorial Rededication……………………………………………………………………….….20 The Czechoslovakian Community Festival……...………………………………………………23 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….28 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………...30 ii Abstract The Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin is a place of both memory and identity for the Czechoslovak community. Built in 1944, the monument initially represented the memory of the victims of the Lidice Massacre in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia while simultaneously symbolizing the patriotic efforts of the Phillips community during World War II. After the memorial’s rededication in 1984 the meaning of the monument to the community shifted. While still commemorating Lidice, the annual commemorations gave rise to the Phillips Czechoslovakian Community Festival held each year. The memorial became a site of cultural identity for the Phillips community and is -

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

Proclamation 5682—July 20, 1987 101 Stat. 2169

PROCLAMATION 5682—JULY 20, 1987 101 STAT. 2169 As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first animated feature-length film, we can be grateful for the art of film animation, which brings to the screen such magic and lasting vitality. We can also be grateful for the con tribution that animation has made to producing so many family films during the last half-century—films embodying the fundamental values of good over evil, courage, and decency that Americans so cherish. Through animation, we have witnessed the wonders of nature, ancient fables, tales of American heroes, and stories of youthful adventure. In recent years, our love for tech nology and the future has been reflected in computer-generated graphic art and animation. The achievements in the motion picture art that have followed since the debut of the first feature-length animated film in 1937 have mirrored the ar tistic development of American culture and the advancement of our Na tion's innovation and technology. By recognizing this anniversary, we pay tribute to the triimiph of creative genius that has prospered in our free en terprise system as nowhere else in the world. We recognize that, where men and women are free to express their creative talents, there is no limit to their potential achievement. In recognition of the special place of animation in American film history, the Congress, by House Joint Resolution 122, has authorized and requested the President to issue a proclamation calling upon the people of the United States to celebrate the week beginning July 16, 1987, with appropriate ob servances of the 50th anniversary of the animated feature film. -

An Oral History Study of the Religiosity of Fifty Czech-American Elderly Christopher Jay Johnson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1981 An oral history study of the religiosity of fifty Czech-American elderly Christopher Jay Johnson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Christopher Jay, "An oral history study of the religiosity of fifty Czech-American elderly " (1981). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7433. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Miscellaneous

MISCELLANEOUS. KLISABET NEY. We publish in this number, as our frontispiece, a photogravure of Schopen- hauer's bust made by Elisabet Ney, a disciple of Rauch, and one of our most prom- inent American artists, who, before she came to the United States, acquired an en- viable European fame. She has modelled from life the busts of many famous men of science, were Humboldt, among whom Jacob Grimm, and Liebig ; of statesmen and heroes, among them Bismarck and Garibaldi ; of artists, among these Kaul- bach and Joachim ; of kings, among these George of Hanover, and a statue of Lud- wig II. of Bavaria, now at the celebrated castle of Linderhoff, etc,, etc. While she lived at Frankfort in 1859, Schopenhauer had not yet attained to the fame of his later years, but Elisabet Ney was interested in the great prophet of pessimism. She was well acquainted with his works, and foresaw the influence which the grumbling misanthrope would wield over all generations to come. She knew very well that he was a woman hater who thought that women could never accomplish anything either in science or in the arts. But this only made her find it the more attractive and humorous to converse with him and prove to him what women could do. Schopenhauer was very much impressed with the young sculptress, and con- fessed to friends of his, as seen in many of his printed letters, that she was an ex- ception to the rule. While he was sitting to have his bust taken, he was as a rule animated and full of interesting gossip, mostly of a philosophical nature. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

EDRS PUCE BF-80.83 Plus Postage

DOCUMENT ISSUES 1 ED 130 783 PS 008 917 TITLE Parenting in 1976s A Listing from PHIC. INSTITUTION Southwest Educational Development Tab.-, Austin, Tex., SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (HEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Bay 76 NOTE 169p.; For 1975 edition, see ED 110 156. AVAILABLE FROMParenting Baterials Inforaation Center, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, 211 East 7th 'Street, Austin, Texas 78701 ($5.00) EDRS PUCE BF-80.83 Plus Postage. BC Not Available froa EDRS. DESCIIPTORS *Bibliographies; Child Abuse; Child Development; Cultural Pluralisa; Discipline4 *Early Childhood Education; Exceptional Children; F4mily (Sociological Unit); Group Relations; Health; Learning Activities; *Parent Education; Parent Participation; *Parents; Parent Teacher Cooperation; Peer Relationship; Prograa Descriptions; *Resource Materials IDENTIFIERS *Parenting Materials Information Center TX ABSTRACT This bibliography lists iaterials, programs and resources which appear to be relevant to the lauds of parents and." those-working with parents.,The bibliography is a project of the Parenting Baterials Information Center (PEIC) being deyeloped by the Southvest Educational Developaent Laboratory.,PEIC colledts, analyzes and disseminates information pertaining to parenting..The list is divided into major content areas according to iaitial classification efforts by the center staff.,These major areas have been designated (1) academic contents and skills; (2) child abuse; (3) discipline;. (4) early childhood activities; (S) education; (6) exceptional children; (7) family; (8) general resources for parenting/family/education; (9) group relationships and training; (10) health and safety; (11) large scale programs; (12) multi-ethnic aulti-cultural heritage and contents; (13) language and intellectual developaent; (14) parent, school and community involveaent; (15) parenting; (16) physical and sensory deprivation;(17). -

American Ethnicity and Czech Immigrants' Integration in Texas: Cemetery Data

AMERICAN ETHNICITY AND CZECH IMMIGRANTS’ INTEGRATION IN TEXAS: CEMETERY DATA EVA ECKERT Anglo-American University, Prague The lasting traces of Czech immigration to Texas and the once prominent immigrant community lead to the cemeteries. The purpose of this study is to show how to read Czech cemetery data in Texas from the 1860s to the 1950s in order to understand the immigrants’ integration and contact with their German neighbors and the dominant Anglo-American society. To immigrants in the middle of the 19th century, Texas offered land and freedom of movement. But the reasons to return home outweighed those to stay for some of the earliest immigrants who were unable to align themselves with networks established by the German immigrants who preceded them. Those who followed the pioneers lived within interethnic social structures that they gradually abandoned in favor of the ethnocentric Czech community. Language choices, the interplay of Czech and English, and the endurance of the Czech language in tombstone inscriptions yield synchronic and diachronic data whose analysis and interpretation reveal sociolinguistic networks of immigrants, rules of social cohesion and ethnic identity. Keywords: Texas Czech cemeteries, immigrant integration, language shift, interethnic networks, ethnocentric Czech community INTRODUCTION Cemetery lands are overlaid with language that is opened to diachronic and synchronic exploration. Chronological data of gravestones resonate with immigrant arrivals. Cemetery inscriptions thus provide a permanent, yet rarely -

Literature, Peda

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE STUDENTS OF HUMAN RIGHTS: LITERATURE, PEDAGOGY, AND THE LONG SIXTIES IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Molly Appel © 2018 Molly Appel Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 ii The dissertation of Molly Appel was reviewed and approved* by the following: Rosemary Jolly Weiss Chair of the Humanities in Literature and Human Rights Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas O. Beebee Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Comparative Literature and German Charlotte Eubanks Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Japanese, and Asian Studies Director of Graduate Studies John Ochoa Associate Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature Sarah J. Townsend Assistant Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Robert R. Edwards Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and Comparative Literature Head of the Department of Comparative Literature *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT In The Students of Human Rights, I propose that the role of the cultural figure of the American student activist of the Long Sixties in human rights literature enables us to identify a pedagogy of deficit and indebtedness at work within human rights discourse. My central argument is that a close and comparative reading of the role of this cultural figure in the American context, anchored in three representative cases from Argentina—a dictatorship, Mexico—a nominal democracy, and Puerto Rico—a colonially-occupied and minoritized community within the United States, reveals that the liberal idealization of the subject of human rights relies upon the implicit pedagogical regulation of an educable subject of human rights. -

Conditions Along the Borderâ•Fi1915 the Plan De San Diego

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 43 Number 3 Article 3 7-1-1968 Conditions Along the Border–1915 The Plan de San Diego Allen Gerlach Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Gerlach, Allen. "Conditions Along the Border–1915 The Plan de San Diego." New Mexico Historical Review 43, 3 (1968). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol43/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 195 CONDITIONS ALONG THE BORDER-1915 THE PLAN DE SAN DIEGO ALLEN GERLACH FROM 1910 to 1916 the\Mexican Republic suffered from acute political instability as one "Plan" after another was issued against claimants to the presidency. The turbulence of the Mexican Revo lution began in 1910 with the overthrow of Porfirio Diaz by the movement of Francisco 1. Madero. In 1913 !he tenuous regime of Madero was violently replaced by that of Victoriano Huerta, and the turmoil continued unabated. Faced with major revolutions led by Venustiano Carranza, Francisco Villa, and Emiliano Zapata, Huerta fled Mexico in mid-1914 as the opposition armies con verged on Mexico City. Despite the efforts of the new victors to achieve a unified government at the Convention of Aguascalientes in 1914, Carranza's Constitutionalists soon fell into quarreling among themselves and the Revolution entered its most violent phase. Representing the Constitutionalist government of Mexico, Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obreg6n arrayed themselves against Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata, who purported to represent the cause of the Convention. -

Stephen F. Austin Books

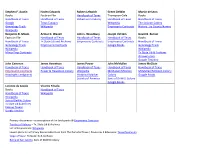

Stephen F. Austin Haden Edwards Robert Leftwich Green DeWitt Martin de Leon Books Facts on File Handbook of Texas Thompson-Gale Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Robertson’s Colony Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Google Texas Escapes Wikipedia The DeLeon Colony Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Empresario Contracts History…by County Names Wikipedia Benjamin R. Milam Arthur G. Wavell John L. Woodbury Joseph Vehlein David G. Burnet Facts on File Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Books Handbook of Texas Tx State Lib and Archives Empresario Contracts Empresario Contracts Handbook of Texas Genealogy Trails Empresario Contracts Google Books Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Wikipedia Minor Emp Contracts Tx State Lib & Archives Answers.com Google Timeline John Cameron James Hewetson James Power John McMullen James McGloin Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Empresario Contracts Power & Hewetson Colony Wikipedia McMullen/McGloin McMullen/McGloin Colony Headright Landgrants Historical Marker Colony Google Books Society of America Sons of DeWitt Colony Google Books Lorenzo de Zavala Vicente Filisola Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Wikipedia Wikipedia Sons of DeWitt Colony Tx State Lib & Archives Famous Texans Google Timeline Primary documents – transcriptions of the land grants @ Empresario Contracts Treaties of Velasco – Tx. State Lib & Archives List of Empresarios: Wikipedia Lesson plans for a Primary Source Adventure from The Portal of Texas / Resources 4 Educators: Texas Revolution Siege of Bexar: Tx State Lib & Archives Battle of San Jacinto: Sons of DeWitt Colony . -

Hill Country Trail Region

Inset: Fredericksburg’s German heritage is displayed throughout the town; Background: Bluebonnets near Marble Falls ★ ★ ★ reen hills roll like waves to the horizon. Clear streams babble below rock cliffs. Wildfl owers blanket valleys in a full spectrum of color. Such scenic beauty stirs the spirit in the Texas Hill Country Trail Region. The area is rich in culture and mystique, from fl ourishing vineyards and delectable cuisines to charming small towns with a compelling blend of diversity in heritage and history. The region’s 19 counties form the hilly eastern half of the Edwards Plateau. The curving Balcones Escarpment defi nes the region’s eastern and southern boundaries. Granite outcroppings in the Llano Uplift mark its northern edge. The region includes two major cities, Austin and San Antonio, and dozens of captivating communities with historic downtowns. Millions of years ago, geologic forces uplifted the plateau, followed by eons of erosion that carved out hills more than 2,000 feet in elevation. Water fi ltered through limestone bedrock, shaping caverns and vast aquifers feeding into the many Hill Country region rivers that create a recreational paradise. Scenic beauty, Small–town charm TxDOT TxDOT Paleoindian hunter-gatherers roamed the region during prehistoric times. Water and wildlife later attracted Tonkawa, Apache and Comanche tribes, along with other nomads who hunted bison and antelope. Eighteenth-century Spanish soldiers and missionaries established a presidio and fi ve missions in San Antonio, which became the capital of Spanish Texas. Native American presence deterred settlements during the era when Texas was part of New Spain and, later, Mexico.