The Marawi Siege and Its Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

Philippines Mindanao Response Humanitarian Situation Update 17 June 2011

Philippines Mindanao Response Humanitarian Situation Update 17 June 2011 This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHA Philippines. It covers the period from 13 May to 16 June 2011. The next report will be issued on or around 18 July. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • Widespread rains over eastern and southern Mindanao have caused flooding and flashfloods in nine provinces of Mindanao, affecting 120,038 families (611,196 individuals). • The Senate has approved the postponement of August 2011 ARMM elections to synchronize it with the 2013 national and local elections. • The members of the Mindanao Humanitarian Team are undertaking the Mid Year Review of the Mindanao Humanitarian Action Plan. I. SITUATION OVERVIEW NATURAL DISASTERS Flooding in Regions X, XI, XII and ARMM Widespread rains over eastern and southern Mindanao due to the presence of Low Pressure Area have caused flooding and flashfloods in nine provinces in Mindanao, affecting 120,038 families (611,196 individuals). NDRRMC (15 June) reported that 48 municipalities, five cities, and 395 barangays in four regions (X, XI, XII and the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM)) have been affected by flooding. A total of 3,130 families (12,875 individuals) are in four Evacuation Centers (one in Malaybalay City, Bukidnon Province and three in North Cotabato). NDRRMC further reported that 7,023 hectares of agricultural crops have been damaged by flooding Residential area along Main road of Barangay in Mindanao, of which 5,391 hectares (or 77 per cent) are in Tamontaka 2, Cotabato City. Photo: Courtesy of Maguindanao. -

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: a Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: A Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution Jamail A. Kamlian Professor of History at Mindanao State University- ILigan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), ILigan City, Philippines ABSTRACT Filipina kini menghadapi masalah serius terkait populasi mioniritas agama dan etnis. Bangsa Moro yang merupakan salah satu etnis minoritas telah lama berjuang untuk mendapatkan hak untuk self-determination. Perjuangan mereka dilancarkan dalam berbagai bentuk, mulai dari parlemen hingga perjuangan bersenjata dengan tuntutan otonomi politik atau negara Islam teroisah. Pemberontakan etnis ini telah mengakar dalam sejarah panjang penindasan sejak era kolonial. Jika pemberontakan yang kini masih berlangsung itu tidak segera teratasi, keamanan nasional Filipina dapat dipastikan terancam. Tulisan ini memaparkan latar belakang historis dan demografis gerakan pemisahan diri yang dilancarkan Bangsa Moro. Setelah memahami latar belakang konflik, mekanisme resolusi konflik lantas diajukan dalam tulisan ini. Kata-Kata Kunci: Bangsa Moro, latar belakang sejarah, ekonomi politik, resolusi konflik. The Philippines is now seriously confronted with problems related to their ethnic and religious minority populations. The Bangsamoro (Muslim Filipinos) people, one of these minority groups, have been struggling for their right to self-determination. Their struggle has taken several forms ranging from parliamentary to armed struggle with a major demand of a regional political autonomy or separate Islamic State. The Bangsamoro rebellion is a deep- rooted problem with strong historical underpinnings that can be traced as far back as the colonial era. It has persisted up to the present and may continue to persist as well as threaten the national security of the Republic of the Philippines unless appropriate solutions can be put in place and accepted by the various stakeholders of peace and development. -

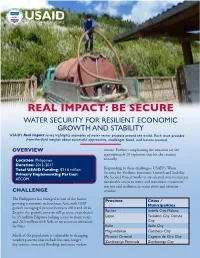

Real Impact: Be Secure Project

REAL IMPACT: BE SECURE WATER SECURITY FOR RESILIENT ECONOMIC GROWTH AND STABILITY USAID’s Real Impact series highlights examples of water sector projects around the world. Each issue provides from-the-field insights about successful approaches, challenges faced, and lessons learned. OVERVIEW storms. Further complicating the situation are the approximately 20 typhoons that hit the country Location: Philippines annually. Duration: 2012–2017 Total USAID Funding: $21.6 million Responding to these challenges, USAID’s Water Security for Resilient Economic Growth and Stability Primary Implementing Partner: AECOM (Be Secure) Project works in six selected sites to increase sustainable access to water and wastewater treatment services and resilience to water stress and extreme CHALLENGE weather. The Philippines has emerged as one of the fastest Province Cities / growing economies in Southeast Asia, with GDP Municipalities growth averaging 6 percent between 2010 and 2016. Basilan Isabela City, Maluso Despite the growth, poverty still persists, exacerbated by 15 million Filipinos lacking access to clean water, Leyte Tacloban City, Ormoc and 26.5 million with little or no access to sanitation City facilities. Iloilo Iloilo City Maguindanao Cotabato City Much of the population is vulnerable to changing Misamis Oriental Cagayan de Oro City weather patterns that include less rain, longer Zamboanga Peninsula Zamboanga City dry seasons, increased flooding, and more violent partnership, the water district upgraded its maintenance department and GIS division, ensuring the sustainability of the NRW program beyond the term of USAID’s support. Be Secure works with water districts to design efficient, new water systems. Equipped with project-procured feasibility studies, Cagayan de Oro and Cotabato cities can now determine the best sites to tap additional water sources as they prepare to meet future demand. -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 10, Issue 9 | September 2018 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH (CTR) The Lamitan Bombing and Terrorist Threat in the Philippines Rommel C. Banlaoi Crime-Terror Nexus in Southeast Asia Bilveer Singh India and the Crime-Terrorism Nexus Ramesh Balakrishnan Crime -Terror Nexus in Pakistan Farhan Zahid Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses Volume 9, Issue 4 | April 2017 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note Terrorist Threat in the Philippines and the Crime-Terror Nexus In light of the recent Lamitan bombing in the detailing the Siege of Marawi. The Lamitan Southern Philippines in July 2018, this issue bombing symbolises the continued ideological highlights the changing terrorist threat in the and physical threat of IS to the Philippines, Philippines. This issue then focuses, on the despite the group’s physical defeat in Marawi crime-terror nexus as a key factor facilitating in 2017. The author contends that the counter- and promoting financial sources for terrorist terrorism bodies can defeat IS only through groups, while observing case studies in accepting the group’s presence and hold in the Southeast Asia (Philippines) and South Asia southern region of the country. (India and Pakistan). The symbiotic Wrelationship and cooperation between terrorist Bilveer Singh broadly observes the nature groups and criminal organisations is critical to of the crime-terror nexus in Southeast Asia, the existence and functioning of the former, and analyses the Abu Sayyaf Group’s (ASG) despite different ideological goals and sources of finance in the Philippines. -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

The Jihadi Industry: Assessing the Organizational, Leadership And

The Jihadi Industry: Assessing the Organizational, Leadership, and Cyber Profiles Report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security July 2017 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Led by the University of Maryland 8400 Baltimore Ave., Suite 250 • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The authors of this report are Gina Ligon, Michael Logan, Margeret Hall, Douglas C. Derrick, Julia Fuller, and Sam Church at the University of Nebraska, Omaha. Questions about this report should be directed to Dr. Gina Ligon at [email protected]. This report is part of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) project, “The Jihadi Industry: Assessing the Organizational, Leadership, and Cyber Profiles” led by Principal Investigator Gina Ligon. This research was supported by the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate’s Office of University Programs through Award Number #2012-ST-061-CS0001, Center for the Study of Terrorism and Behavior (CSTAB 1.12) made to START to investigate the role of social, behavioral, cultural, and economic factors on radicalization and violent extremism. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. -

U.S. Military Engagement in the Broader Middle East

U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT U.S. MILITARY ENGAGEMENT IN THE BROADER MIDDLE EAST JAMES F. JEFFREY MICHAEL EISENSTADT THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY WWW.WASHINGTONINSTITUTE.ORG The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. Policy Focus 143, April 2016 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing fromthe publisher. ©2016 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1111 19th Street NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: An F-16 from the Egyptian Air Force prepares to make contact with a KC-135 from the 336th ARS during in-flight refueling training. (USAF photo by Staff Sgt. Amy Abbott) Contents Acknowledgments V I. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF U.S. MILITARY OPERATIONS 1 James F. Jeffrey 1. Introduction to Part I 3 2. Basic Principles 5 3. U.S. Strategy in the Middle East 8 4. U.S. Military Engagement 19 5. Conclusion 37 Notes, Part I 39 II. RETHINKING U.S. MILITARY STRATEGY 47 Michael Eisenstadt 6. Introduction to Part II 49 7. American Sisyphus: Impact of the Middle Eastern Operational Environment 52 8. Disjointed Strategy: Aligning Ways, Means, and Ends 58 9. -

Pacnet Number 7 Jan

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 7 Jan. 19, 2016 Islamic State branches in Southeast Asia by Rohan Ma’rakah Al-Ansar Battalion led by Abu Ammar; 3) Ansarul Gunaratna Khilafah Battalion led by Abu Sharifah; and 4) Al Harakatul Islamiyyah Battalion in Basilan led by Isnilon Hapilon, who is Rohan Gunaratna ([email protected]) is Professor of the overall leader of the four battalions. Al Harakatul Security Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of Security Islamiyyah is the original name of ASG. Referring to Hapilon Studies (RSIS) and head of the International Centre for as “Sheikh Mujahid Abu Abdullah Al-Filipini,” an IS official Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) at RSIS, organ Al-Naba’ reported on the unification of the “battalions” Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Earlier of God’s fighters (“mujahidin”). The IS choice of Hapilon to versions of this article appeared in The Straits Times and as lead an IS province in the Philippines presents a long-term RSIS Commentary 004/2016. threat to the Philippines and beyond. The so-called Islamic State (IS) is likely to create IS At the oath-taking to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, the battalions branches in the Philippines and Indonesia in 2016. Although were represented by Ansar Al-Shariah Battalion leader Abu the Indonesian military pre-empted IS plans to declare a Anas Al-Muhajir who goes by the alias Abraham. Abu Anas satellite state of the “caliphate” in eastern Indonesia, IS is Al-Muhajir is Mohammad bin Najib bin Hussein from determined to declare such an entity in at least one part of Malaysia and his battalion is in charge of laws and other Southeast Asia. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19 -

Toward Peace in the Southern Philippines

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT G. Eugene Martin and Astrid S. Tuminez In 2003 the U.S. Department of State asked the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) to undertake a project to help expedite a peace agreement between the government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The MILF has been engaged in a rebellion against the GRP for more than three decades, Toward Peace in the with the conflict concentrated on the southern island of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. This report highlights USIP activities in the Philippines from 2003 to 2007. It Southern Philippines describes the conflict and its background, the substance of ongoing negotiations, USIP efforts to “facilitate” the peace process, and insights on potentially constructive steps for A Summary and Assessment of the USIP moving the Philippine peace talks forward. It concludes with a few lessons learned from USIP’s engagement in this Philippine Facilitation Project, 2003–2007 specific conflict, as well as general observations about the potential value of a quasi-governmental entity such as USIP in facilitating negotiations in other conflicts. G. Eugene Martin was the executive director of the Philippine Facilitation Project. He is a retired Foreign Summary Service officer who served as deputy chief of mission at the • The Muslim inhabitants of Mindanao and Sulu in the southern Philippines, known U.S. Embassy in Manila. Astrid S. Tuminez served as the project’s senior research associate. -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board.