Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 6-2011 The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England Cassandra Auble University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Auble, Cassandra, "The Cultural Significance of Precious Stones in Early Modern England" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 39. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PRECIOUS STONES IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND by Cassandra J. Auble A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Carole Levin Lincoln, Nebraska June, 2011 THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF PRECIOUS STONES IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND Cassandra J. Auble, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: Carole Levin Sixteenth and seventeenth century sources reveal that precious stones served a number of important functions in Elizabethan and early Stuart society. The beauty and rarity of certain precious stones made them ideal additions to fashion and dress of the day. These stones also served political purposes when flaunted as examples of a country‘s wealth, bestowed as favors, or even worn as a show of royal support. -

This Thesis Is Being Submitted in Partial Futfilment of the Degree of Phd by Prior Publication

The historical roles of minerol materials in folk medicine and the development of the materia medicu Christopher John DUFFIN This thesis is being submitted in partial futfilment of the requirements of the University of Kingston for the degree of PhD by prior publication January,2018 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my wife, Yvonne Duffin (1950-2015), who appreciated and supported my consuming interest in the subject investigated in these pages. Abstract Mineral materials include rocks, minerals, fossils, earths, mineraloids, biogenic skeletal remains and synthetic stones. Each of these classes of material has enjoyed much popularity as supposedly therapeutic medicinal ingredients in the history of pharmacy; many have an unbroken record of use since ancient and classical times. The historical materia medica incorporates minerals that have been made use of in both medical folklore and academic analysis. This thesis presents a body of work which develops examples from each class of mineral material, tries to establish their identities, and explores the evolution of their therapeutic use against the backdrop of changing philosophies in the history of medicine. The most rudimentary use of mineral materials was in a magico-medicinal way as amulets wom for protection against harmful influences which might be expressed in the body as loss of health, and as prophylactics against specific diseases and poisons. Amulets were often worn as pendants, necklaces and rings, or appended to the clothing in some way. The humoral system of Greek medicine saw the health of the body as being a state of balance between the four humours. Humoral imbalance was corrected by, amongst other interventions, the application of medicinal simples or 'Galenicals', which were largely unmodified (other than by trituration) herbal, zoological and mineralogical materials. -

A Close Study of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historia

SUMMA ABSOLUTAQUE NATURAE RERUM CONTEMPLATIO: A CLOSE STUDY OF PLINY THE ELDER’S NATURALIS HISTORIA 37 by EMILY CLAIRE BROWN B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2010 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Classics) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2012 © Emily Claire Brown, 2012 ABSTRACT The focus of modern scholarship on Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia tends towards two primary goals: the placement of the work and the author within the cultural context of late 1st century CE Rome and, secondly, the acknowledgement of the purposeful and designed nature of Pliny’s text. Following this trend, the purpose of this study is to approach Book 37, in which Pliny lists and categorizes the gems of the world, as a deliberately structure text that is informed by its cultural context. The methodology for this project involved careful readings of the book, with special attention paid to the patterns hidden under the surface of Pliny’s occasionally convoluted prose; particular interest was paid to structural patterns and linguistic choices that reveal hierarchies. Of particular concern were several areas that appealed to the most prominent areas of concern in the book: the structure and form of the book; the colour terminology by which Pliny himself categorizes the gems; the identification of gems as objects of mirabilia and luxuria; and the identification of gems as objects of magia and medicina. These topics are all iterations of the basic question of whether gems represent to Pliny positive growth on the part of the Roman Empire, or detrimental decline. -

Dark Transparencies: Crystal Poetics in Medieval Texts and Beyond

Dark Transparencies: Crystal Poetics in Medieval Texts and Beyond Marisa Galvez ecent studies on medieval stones have examined the lithic ef- ficacy and agency inherent in the lapidary tradition dating back Rto Greece, a tradition that continues in writings about mineral virtus in the Middle Ages through authors such as Isidore of Seville and Albertus Magnus. In particular, attention has been paid to how inanimate objects serve as a topos for exploring the engagement of humans with non-humans.1 Critics such as Bill Brown, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, and Kellie Robertson have challenged the Heideggerian notion of inert “worldless” (weltlos) objects impoverished of animal captivation (Benommenheit) or human apprehending (Vernehmen) by arguing that such objects or things “matter” and have the potential to be “world-forming”: in Cohen’s assess- ment, humans are not the “world’s sole meaning-maker,” and Brown argues for “things” as impenetrable objects that resist human utilization for con- cepts and instead produce a “force as a sensuous presence.”2 This essay proposes a different reading of stones that draws upon these ethical and theoretical reflections on things and objects. A comparative reading of secular medieval literature of the twelfth and thirteenth centu- ries left out of these studies can nuance our modern preoccupation with things as challenging a human-centered view of the world. Courtly texts that focus on erotic desire show that medieval readers understood the her- meneutic tension between an object such as stone that could hold meaning for the human interpreter, and a formless, transforming thing with various physical effects in particular moments or through time—what I shall call a “substantive” materiality. -

The Art of Glassmaking and the Nature of Stones the Role of Imitation in Anselm De Boodt’S Classification of Stones

Sven Dupré The Art of Glassmaking and the Nature of Stones The Role of Imitation in Anselm De Boodt’s Classification of Stones I n Gemmarum et lapidum historia, published in 1609, and arguably the most important work on stones of the seventeenth century, the Flemish physician Anselm De Boodt included precious stones, such as diamonds, lapis lazuli, emeralds (fig. 1), jade, nephrite and agate imported to Europe from Asia and the New World.1 The book was illustrated with specimens from the collection of Rudolf II in Prague where De Boodt was court physician, and the successor of Carolus Clusius as overseer of Rudolf’s gardens.2 De Boodt also included stones mined and sculpted in Europe, such as various marbles, porphyry, alabaster and rock crystal, as well as stones of organic origin, such as amber and coral (fig. 2), some fossils and a diversity of animal body stones, the bezoar stone being the most famous.3 Beyond simply listing stones across the lines between the organic and the inor- ganic, the vegetative and the mineral, the natural and the artificial, as was standard prac- tice in the lapidary tradition stretching back to Theophrastus and Antiquity, De Boodt also offered a classification of stones.D espite his importance, little work has been done on De Boodt. One exception is work by Annibale Mottana, who argues that “De Boot (sic) wanted to show his contempt for the merchant approach to gemstones in an attempt to 1 This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 648718), and has been supported by a Robert H. -

The Art of the Lapidary

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OP NATURAL HISTORY THE ART OF THE LAPIDARY By HERBERT P. WHITLOCK OUIDE LEAFLET SERIES No. 65 DECEMBER, 1926 With it 444 perfectly proportion d fa ets t hi blue T opaz a marvelou ex pres ion f the art of the lapidary. ( ase VT) THE ART OF THE LAPIDARY BY H ERB ER1' P. \ i\ HITLOCK Curator of Vlineralogy G IDE LEAFLET No. 65 THE A~IERICAN l\1 E ~1 OF NAT RAL HI TORY ~ EW Y ORK, D ECEMBER, 1926 "And they were stronger hands than mine That digged the Ruby from the earth More cunning brains that made it worth The large desire of a King." -Rudyard Kipling The Art of the Lapidary INTRODUCTION Although a gem mineral in the rough always exhibit certain quali tie , which, to a di cernino- eye, give promi e of it po ibilitie a a gem, it i through the shaping and facetting of these bits of mineral that their real charm i developed. Gem tone are, in general, cut 1.-To bring out beauties of color. 2.-To adapt them to jewelry form . 3.-To develop the cintillatino- reflections from the interior of the tone by makino- use of the principle of refraction of light. Th fir t two of the e con ideration are too obviou to require more than a word of explanation. The urface of a tran parent uncut o-em tone may be compared to the urface of a~body of water rendered rouo-h and broken by waves and ripples. It is only when uch a urface ha been rendered mooth that we are enabled to look down into the depth below and ee to be t advantage its color. -

Lapidary Works of Art, Gemstones and Minerals

S L RT, RT, A INERA M GEMSTONES AND December 6, 2017 Wednesday Los Angeles LAPIDARY WORKS OF LAPIDARY LAPIDARY WORKS OF ART, GEMSTONES AND MINERALS | Los Angeles, Wednesday DECEMBER 6, 2017 24276 LAPIDARY WORKS OF ART, GEMSTONES AND MINERALS Wednesday December 6, 2017 at 10am Los Angeles BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 (323) 850 7500 Claudia Florian, G.J.G Front cover: Lot 2466 Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Co-Consulting Director Inside front cover: Lot 2035 bonhams.com (323) 436-5437 Session page: Lot 2217 To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 2285 PREVIEW www.bonhams.com/24276 Back cover: Lot 2462 Friday, December 1, 12-5pm Katherine Miller Saturday, December 2, 12-5pm Please note that telephone bids Business Administrator Sunday, December 3, 12-5pm must be submitted no later (323) 436-5445 Monday, December 4, 10-5pm than 4pm on the day prior to [email protected] Tuesday, December 5, 10-5pm the auction. New bidders must also provide proof of identity SALE NUMBER: 24276 and address when submitting Lots 2001 - 2487 bids. Telephone bidding is only available for lots with a low CATALOG: $35 estimate in excess of $1000. Please contact client services with any bidding inquiries. Please see pages 183 to 186 for bidder information including Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Bonhams 220 San Bruno Avenue San Francisco, California 94103 © 2017, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. Bond -

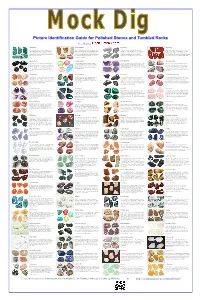

Picture Identification Guide for Polished Stones and Tumbled Rocks Provided By

Picture Identification Guide for Polished Stones and Tumbled Rocks Provided by Amazonite Coral, Agatized Lepidolite Red Jasper Amazonite is a green microcline feldspar. It is A rare find is fossil coral that has been replaced by Lepidolite is a variety of mica that occurs in a Jasper is an opaque chalcedony and red is one of its named after the Amazon River of South America, agate - or agatized. This type of fossilization often spectrum of colors that range from pink to deep most common colors. This red jasper from South where the first commercial deposits were found. preserves the structure of the coral individual or lavender. The stones shown here are tumbled Africa has a fire-engine red color that in some The stones shown here are a rich green Amazonite colony. The result can be a beautiful stone that can quartz pebbles that have enough lepidolite stones is interrupted by a white to transparent quartz that was mined in Russia. be polished to display cross and lateral sections inclusions to yield pink and lavender gemstones. vein. It often accepts an exceptionally high polish. through the coral fossil. Apache Tears Crackle Quartz Lilac Amethyst Rhodonite - Pink Apache Tears are round nodules of obsidian that "Crackle Quartz" is a name used for quartz Amethyst is a purple variety of crystalline quartz that Rhodonite is a metamorphic manganese mineral can be transparent through translucent. When it has polish to a beautiful jet black color. If you hold them specimens that have been heat treated and then that is well known for its beautiful pink color. -

The Materiality of Devotion in Late Medieval Bruges

chapter 12 Amber, Blood, and the Holy Face of Jesus: the Materiality of Devotion in Late Medieval Bruges Elliott D. Wise and Matthew Havili The ‘precious blood of Christ’ is at the core of sacramental mystery.*,1 St. Paul defends its privileged status throughout his epistles, declaring that ‘almost all things are by the law purged with blood; and without shedding of blood is no remission’.2 He emphasizes that the blood sacrifices once required by the Mosaic Law find their antitype in Christ’s Passion and the ‘propitiation through faith in his blood’.3 In the liturgy, there are few substances bodied forth with more consistency and variety than this atoning blood. The newly baptized figuratively ‘was[h] their robes […] white in the blood of the Lamb’, and in the Eucharistic ‘cup [of] the new testament in [his] blood’ the sanguis Christi is adored under the accidentals of bread and wine.4 St. Thomas Aquinas (1225−1274) declared that ‘by His Passion [Christ] inaugurated the Rites of the Christian Religion’, ‘that the sacraments of the Church derive their power spe- cially from Christ’s Passion’, and ‘[i]t was in sign of this that from the side of Christ hanging on the Cross there flowed water and blood’.5 Late medieval and early modern art represents those twin rivers from Christ’s side – the ‘headwa- ters’ of salvation – under a variety of forms and media. This essay will consider the material of amber as a particularly potent signifier for Christ’s historical and sacramental blood. The physical and spiritual qualities of amber would * N. -

Lithika: Ancient Medical and Technical Texts on Stones

Lithika: Ancient Medical and Technical Texts on Stones. In his introduction of Natural History, Pliny lists about 20 Greek writers as authorities for his book XXXVII on minerals and precious stones, but, of the works of these authors, only the brief, or fragmentary, treatise on stones by Theophrastus has survived to inform us in a direct way of the extent of Greek learning in this field. In his On Stones (Περὶ λίθων), Theophrastus is concerned with stones that are rare or have some special quality (Eichholz 1965: I 6): “Numerous stones… possess the characteristic differences in respect of color, hardness, softness, and other such qualities which cause them to be exceptional (δι’ὧν τὸν περιττὸν).” Theophrastus was one of the earliest technical writers on stones and his work dates around 315–14 BCE (Eichholz 1965: 8-11). M. Smith (2004) has pointed out that Posidippus is relying to some degree on technical writing like Theophrastus’ On Stones and, from his technical sources, the Greek epigrammatic poet could derive his details about stones and their exceptional properties. Nearly all of the stones mentioned in Posidippus’ epigrams are also treated by Theophrastus. So far, Theophrastus’ On Stones and Pliny’s book XXXVII of the Natural History stand as bookends of technical writing on stones (Wellman 1935). Furthermore, stones – and, to a lesser degree, also precious stones – held an important role in ancient medicine, especially in pharmacy and pharmacology. Some physicians dedicated a book or a chapter in their writings to stones, numbering bigger or smaller amounts of various minerals, from salts and common stones to more precious stones and gems. -

Dual-Color Double Stars in Ruby, Sapphire, and Quartz

FEATURE ARTICLES DUAL -C OLOR DOUBLE STARS IN RUBY , SAPPHIRE , AND QUARTZ : CAUSE AND HISTORICAL ACCOUNT Karl Schmetzer, Martin P. Steinbach, H. Albert Gilg, and Andrea R. Blake A largely overlooked form of asterism consisting of dual-color double stars is found in natural sapphire, in diffusion-treated and non-diffusion-treated synthetic rubies and sapphires, and in natural quartz. To characterize and explain this phenomenon, examples of these materials were examined. In transparent or translucent samples, an optical pattern of a white six-rayed star and a bodycolored (e.g., red, orange, yellow, green, blue) six-rayed star was frequently observed. Grinding and repolishing experiments showed that the asterism of part of the synthetic samples was produced or enhanced by diffusion treat - ment. The mechanism responsible for the formation of the dual-color double stars is discussed. To pro - duce the pattern, acicular inclusions must either be present in relatively thin layers confined to the dome and the base of diffusion-treated ruby or sapphire cabochons, or be distributed throughout the complete corundum (natural or synthetic) or quartz samples. The white star is caused by interaction of light with the upper layer of the cabochon’s dome. The bodycolored star, in contrast, is generated by light that enters the cabochon, is reflected and scattered at the base layer of the cabochon, and then travels a sec - ond time back through the body of the sample. As further prerequisites for observation of the phenom - enon, the gemstones must be transparent or translucent, with polished base and dome. A historical summary of the manufacture and improvement of synthetic asteriated corundum by dif - fusion treatment offers additional insight into dual-color double-star stones.