The Art of the Lapidary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Combined Metalworking Techniques: Forged Elements and Chased Raised Shapes Bonnie Gallagher

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 1972 Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes Bonnie Gallagher Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Gallagher, Bonnie, "Treatise on combined metalworking techniques: forged elements and chased raised shapes" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TREATISE ON COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES i FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES TREATISE ON. COMBINED METALWORKING TECHNIQUES t FORGED ELEMENTS AND CHASED RAISED SHAPES BONNIE JEANNE GALLAGHER CANDIDATE FOR THE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THE COLLEGE OF FINE AND APPLIED ARTS OF THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUGUST ( 1972 ADVISOR: HANS CHRISTENSEN t " ^ <bV DEDICATION FORM MUST GIVE FORTH THE SPIRIT FORM IS THE MANNER IN WHICH THE SPIRIT IS EXPRESSED ELIEL SAARINAN IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER, WHO LONGED FOR HIS CHILDREN TO HAVE THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE THE EDUCATION HE NEVER HAD THE FORTUNE TO OBTAIN. vi PREFACE Although the processes of raising, forging, and chasing of metal have been covered in most technical books, to date there is no major source which deals with the functional and aesthetic requirements -

Castingmetal

CASTING METAL Sophistication from the surprisingly simple with a room casting. Hmmmm. I I asked Beth where in the world she BROOM pored through every new and learned how to cast metal using the Bvintage metals technique book Brad Smith offers a Broom business end of a broom. “It’s an old BY HELEN I. DRIGGS on my shelf and I couldn’t find a men- Casting Primer, page 32, hobbyist trick. I learned about it from a tion of the process anywhere. This and a project for using very talented guy named Stu Chalfant the elements you cast. transformed my curiosity into an who gave a demo for my rock group TRYBROOM-CAST IT YOURSELFE urgent and obsessive quest. I am an G — the Culver City [California] Rock & A TURQUOISE PENDANT P information junkie — especially Mineral Club. This was six or seven when it comes to studio jewelry — years ago, and I instantly fell in love and I love finding out new, old fash- with the organic, yet orderly shapes.” ioned ways of doing things. But, I am also efficient. So I A few years passed before Beth tried the technique her- knew the best way to proceed was to seek out Beth self. “The first of our club members to experiment with it Rosengard, who has transformed this delightfully low-tech was Brad 34Smith, who now includes the technique in the approach to molten metal into a sophisticated level of artis- classes he teaches at the Venice Adult School.” After admir- tic expression. I had made a mental note to investigate ing some early silver castings Brad had made, she begged broom casting when I saw her winning earrings in the 2006 him for a sample and later incorporated his work into her Jewelry Arts Awards. -

Download Course Outline for This Program

Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork NUNAVUT INUIT LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) PROGRAM REPORT 434 Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Status: Approved Action Type: N/A Change Type: N/A Discontinued: No Latest Version: Yes Printed: 03/30/2015 1 Program Outline 434- Jewellery and Metalwork Program Details 434 - Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term: No Specified End Date End Term: No Specified End Date Program Details Code 434 Title Jewellery and Metalwork Start Term No Specified End Date End Term No Specified End Date Total Credits Institution Nunavut Faculty Inuit Languages and Cultures Department Jewelry and Metalwork (and all fine arts) General Information Eligible for RPL No Description The Program in Jewellery and Metalwork will enable students to develop their knowledge and skills of jewellery and metalwork production in a professional studio atmosphere. To this end the program stresses high standards of craftship and creativity, all the time encouraging and exposing students to a wide range of materials, techniques and concepts. This program is designed to allow the individual student to specialize in an area of study of particular interest. There is an emphasis on creative thinking and problem-solving throughout the program.The first year of the program provides an environment for the students to acquire the necessary skills that will enable them to translate their ideas into two and three dimensional jewellery and metalwork. This first year includes courses in: Drawing and Design, Inuit Art and Jewellery History, Lapidary and also Business and Communications. -

Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist March 2012

INDEX TO VOLUME 65 Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist April 2011-March 2012 INDEX BY FEATURE/ Signature Techniques Part 1 Resin Earrings and Pendant, PROJECT/DEPARTMENT of 2, 20, 09/10-11 30, 08-11 Signature Techniques Part 2 Sagenite Intarsia Pendant, 50, With title, page number, of 2, 18, 11-11 04-11 month, and year published Special Event Sales, 22, 08-11 Silver Clay and Wire Ring, 58, When to Saw Your Rough, 74, 03-12 FEATURE ARTICLES Smokin’*, 43, 09/10-11 01/02-12 Argentium® Tips, 50, 03-12 Spinwheel, 20, 08-11 Arizona Opal, 22, 01/02-12 PROJECTS/DEMOS/FACET Stacking Ring Trio, 74, Basic Files, 36, 11-11 05/06-11 DESIGNS Brachiopod Agate, 26, 04-11 Sterling Safety Pin, 22, 12-11 Alabaster Bowls, 54, 07-11 Create Your Best Workspace, Swirl Step Cut Revisited, 72, Amethyst Crystal Cross, 34, 28, 11-11 01/02-12 Cut Together, 66, 01/02-12 12-11 Tabbed Fossil Coral Pendant, Deciphering Chinese Writing Copper and Silver Clay 50, 01/02-12 Linked Bracelet, 48, 07-11 12, 07-11 Stone, 78, 01/02-12 Torch Fired Enamel Medallion Site of Your Own, A, 12, 03-12 Easier Torchwork, 43, 11-11 Copper Wire Cuff with Silver Necklace, 33, 09/10-11 Elizabeth Taylor’s Legendary Wire “Inlay,” 28, 07-11 Trillion Diamonds Barion, 44, SMOKIN’ STONES Jewels, 58, 12-11 Coquina Pendant, 44, 05/06-11 Alabaster, 52, 07-11 Ethiopian Opal, 28, 01/02-12 01/02-12 Turquoise and Pierced Silver Ametrine, 44, 09/10-11 Find the Right Findings, 46, Corrugated Copper Pendant, Bead Bracelet – Plus!, 44, Coquina, 42, 01/02-12 09/10-11 24, 05/06-11 04-11 Fossilized Ivory, 24, 04-11 -

THE CUTTING PROPERTIES of KUNZITE by John L

THE CUTTING PROPERTIES OF KUNZITE By John L. Ramsey In the process of cutting l~unzite,a lapidary comes THE PROBLEMS OF PERFECT CLEAVAGE face-to-face with problem properties that sometimes AND RESISTANCE' TO ABRASION remain hidden from the jeweler. By way of ex- amining these problems, we present the example of Kunzite is a variety of spodumene, a lithium alu- a one-kilo kunzite crystal being cut. The cutting minum silicate (see box). Those readers who are problems shown give ample warning to the jeweler familiar with either cutting or mounting stones to take care in working with kunzite and dem- in jewelry are aware of the problems that spodu- onstrate the necessity of cautioning customers to mene, in this case kunzite, invariably poses. For avoid shocking the stone when they wear it in those unfamiliar, it is important to note that kun- jewelry. zite has two distinct cleavages. Perfect cleavage in a stone means that splitting, when it occurs, tends to produce plane surfaces. Cleavage in two directions means that the splitting can occur in The difficulties inherent in faceting lzunzite are a plane along either of two directions in the crys- legendary to the lapidary. Yet the special cutting tal. The property of cleavage, while not desirable problems of this stone also provide an important in a gemstone, does not in and of itself mean trou- perspective for the jeweler. The cutting process ble. For instance, diamond tends to cleave but reveals all of the stone's intrinsic mineralogical splits with such difficulty that diamonds are cut, problems to anyone who works with it, whether mounted, and worn with little trepidation. -

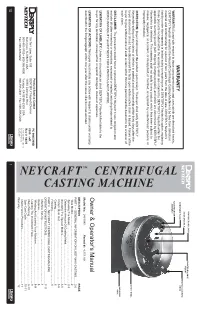

Neycraft Centrifugal Casting Machine to Be Free from Defects in Material and Workmanship for a Period of Two Years from the Date of Sale

CRUCIBLE SLIDE LEVER COUNTER BALANCE WEIGHT SILICA CRUCIBLE WINDING & LOCKING WARRANTY INVESTMENT FLASK KNOB FLASK RECEIVER WARRANTY: Except with respect to those components parts and uses which are described herein, ASSEMBLY DENTSPLY Neytech warrants the Neycraft Centrifugal Casting Machine to be free from defects in material and workmanship for a period of two years from the date of sale. DENTSPLY Neytech’s liability under this warranty is limited solely to repairing or, at DENTSPLY Neytech’s option, replacing those products included within the warranty which are returned to DENTSPLY Neytech within the applicable warranty period (with shipping charges prepaid), and which are determined by DENTSPLY Neytech to be defective. This warranty shall not apply to any product which has been subject to misuse; negligence; or accident; or misapplied; or modified; or repaired by unauthorized persons; or improperly installed. INSPECTION: Buyer shall inspect the product upon receipt. The buyer shall notify DENTSPLY Neytech in writing of any claims of defects in material and workmanship within thirty days after the buyer discovers or should have discovered the facts upon which such a claim is based. Failure of the SAFETY SHELL buyer to give written notice of such a claim within this time period shall be deemed to be a waiver of such claim. MOUNTING BASE DISCLAIMER: The provisions stated herein represent DENTSPLY Neytech’s sole obligation and exclude all other remedies or warranties, expressed or implied, including those related to MERCHANTABILITY and FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY: Under no circumstances shall DENTSPLY Neytech be liable to the buyer for any incidental, consequential or special damages, losses or expenses. -

Estate Jewelry Their Signed Work Consistently Fetches a Premium—Sometimes up to Three Times the ESTATE JEWELRY Only Reliable Source

HOW TO BUY Most estate dealers insist that the finest pieces never go on display. In addition JAR workshop at Place Vendôme turns out heirloom pieces that regularly earn two to Deco-era Cartier, the market is perpetually starved for natural (as opposed to cul- to three times their estimates at auction. Other designers to watch include Munich- tured) pearls and über-rare gemstones: Kashmir sapphires, “pigeon’s blood” Burmese based Hemmerle and New York’s Taffin, by James de Givenchy, a nephew of the cel- rubies from the fabled tracts of Mogok, Golconda diamonds. Most of the mines that ebrated couturier Hubert de Givenchy. produce these treasured gems have long since closed, making estate jewelry their Signed work consistently fetches a premium—sometimes up to three times the ESTATE JEWELRY only reliable source. value of a similar but unsigned piece. Greg Kwiat, the new CEO of Fred Leighton, says BY VICTORIA GOMELSKY “We have about a half-dozen people we call” when something special turns up, he recently inspected an important 1930s diamond necklace by Van Cleef & Arpels: says Walter McTeigue, co-founder of high-end jeweler McTeigue & McClelland, citing “On the strength of that signature, we increased our offer by 50 percent.” The provenance of a major piece of jewelry can often add to its allure and its retail value. an oil-shipping magnate, a publish- Add a well-documented prove- ing heiress, and a star hedge-fund M.S. Rau Antiques nance to the mix, and all bets are off. manager as clients who make his Jacques-Charles “A Cartier bandeau that was once But be sure you get the story straight before you hand over the cash Mongenot Louis XVI short list. -

METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub

Arts & Communication METAL ENAMELING Leader Guide Pub. No. CIR009 WISCONSIN 4-H PUBLICATION HEAD HEART HANDS HEALTH Contents Before Each Meeting: Checklist ..............................1 Adhesive Agents or Binders ....................................6 Facilities Tools, Materials and Equipment Safety Precautions..................................................6 Resource Materials Kiln Firing and Table-Top Units Expenses Metal Cutting and Cleaning Planning Application of Enamel Colors Youth Leaders Other Cautions Project Meeting: Checklist ......................................3 Metal Art and Jewery Terms ...................................7 Purposes of 4-H Arts and Crafts ...........................................8 Components of Good Metal Enameling Futher Leader Training Sources of Supplies How to Start Working Prepare a Project Plan Bibiography ............................................................8 Evaluation of Projects Kiln Prearation and Maintenance ...........................6 WISCONSIN 4-H Pub. No. CIR009, Pg. Welcome! Be sure all youth are familiar with 4H158, Metal Enameling As a leader in the 4-H Metal Enameling Project, you only Member Guide. The guide suggests some tools (soldering need an interest in young people and metal enameling to be irons and propane torches), materials and methods which are successful. more appropriate for older youth and more suitable for larger facilities (school art room or spacious county center), rather To get started, contact your county University of Wisconsin- than your kitchen or basement. Rearrange these recommen- Extension office for the 4-H leadership booklets 4H350, dations to best suit the ages and abilities of your group’s Getting Started in 4-H Leadership, and 4H500, I’m a 4-H membership and your own comfort level as helper. Project Leader. Now What Do I Do? (also available on the Wisconsin 4-H Web Site at http://www.uwex.edu/ces/4h/ As in any art project, a generous supply of tools and pubs/index.html). -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

Studio Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC

Studio Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC Summer 2005 · Volume 8, Number 2 Studio Summer 2005 · Volume 8, Number 2 Member Magazine of the PMC Guild PMC On the Cover: Gang blade from PMC Tool and Supply/Darway features Design Studio, leaf cutters and rolling tool from Celie Fago, and tool kit from New Mexico Clay. Background image is Elaine Luther working on her butterfly pendant... see page 7 4 Word Art Studio PMC This beginner's project by Debbie Fehrenbach using rubber stamps is PMC Guild ideal for teaching the technique. P.O. Box 265, Mansfield, MA 02048 www.PMCguild.com 6 Butterfly Inlay Pendant Volume 8, Number 2 • Summer 2005 Editor—Suzanne Wade Elaine Luther demonstrates the use of some of her favorite tools Technical Editor—Tim McCreight in this pendant project. Art Director—Jonah Spivak Advertising Manager—Bill Spilman Studio PMC is published by the PMC Guild Inc. 10 The Tool Trade • How to SUBMIT WORK to Studio PMC… For some PMC artists, developing and selling tools has become We welcome your PMC photos, articles and ideas. You may submit by mail or electronically. Please include your name, address, e-mail, a welcome addition to their PMC careers. phone, plus a full description of your PMC piece and a brief bio. Slides are preferred, but color prints and digital images are OK. By Mail: Mail articles and photos to: Studio PMC, 11 Tools, Tools, Tools P.O. Box 265, Mansfield, MA 02048. Electronically: E-mail articles in the body of the e-mail, or as Studio PMC's First Tool Buyers' Guide! A treasure trove of tools attachments. -

Tensions Between Scientia and Ars in Medieval Natural Philosophy and Magic Isabelle Draelants

The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic Isabelle Draelants To cite this version: Isabelle Draelants. The notion of ‘Properties’ : Tensions between Scientia and Ars in medieval natural philosophy and magic. Sophie PAGE – Catherine RIDER, eds., The Routledge History of Medieval Magic, p. 169-186, 2019. halshs-03092184 HAL Id: halshs-03092184 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03092184 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This article was downloaded by: University College London On: 27 Nov 2019 Access details: subscription number 11237 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Sophie Page, Catherine Rider The notion of properties Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 Isabelle Draelants Published online on: 20 Feb 2019 How to cite :- Isabelle Draelants. 20 Feb 2019, The notion of properties from: The Routledge History of Medieval Magic Routledge Accessed on: 27 Nov 2019 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613192-14 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

Evaluation of Brilliance, Fire, and Scintillation in Round Brilliant

Optical Engineering 46͑9͒, 093604 ͑September 2007͒ Evaluation of brilliance, fire, and scintillation in round brilliant gemstones Jose Sasian, FELLOW SPIE Abstract. We discuss several illumination effects in gemstones and University of Arizona present maps to evaluate them. The matrices and tilt views of these College of Optical Sciences maps permit one to find the stones that perform best in terms of illumi- 1630 East University Boulevard nation properties. By using the concepts of the main cutter’s line, and the Tucson, Arizona 85721 anti-cutter’s line, the problem of finding the best stones is reduced by E-mail: [email protected] one dimension in the cutter’s space. For the first time it is clearly shown why the Tolkowsky cut, and other cuts adjacent to it along the main cutter’s line, is one of the best round brilliant cuts. The maps we intro- Jason Quick duce are a valuable educational tool, provide a basis for gemstone grad- Jacob Sheffield ing, and are useful in the jewelry industry to assess gemstone American Gem Society Laboratories performance. © 2007 Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers. 8917 West Sahara Avenue ͓DOI: 10.1117/1.2769018͔ Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 Subject terms: gemstone evaluation; gemstone grading; gemstone brilliance; gemstone fire; gemstone scintillation; gemstone cuts; round brilliant; gemstones; diamond cuts; diamonds. James Caudill American Gem Society Advanced Instruments Paper 060668R received Aug. 28, 2006; revised manuscript received Feb. 16, 8881 West Sahara Avenue 2007; accepted for publication Apr. 10, 2007; published online Oct. 1, 2007. Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 Peter Yantzer American Gem Society Laboratories 8917 West Sahara Avenue Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 1 Introduction are refracted out of the stone.