Reviews Marvels & Tales Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Program

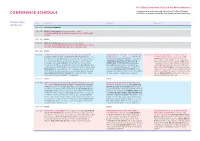

The 15th International Child and the Book Conference Transformation and Continuity: Political and Cultural Changes CONFERENCE SCHEDULE in Children’s Literature from the Past Century to the Present Day Wednesday, TIME SESSION 1 SESSION 2 SESSION 3 24 March 10:30 – 11:00 WELCOMING CEREMONY 11:00 – 12:00 KEYNOTE Detlef Pech (prerecorded presentation + Q&A) HISTORICAL AWARENESS: CHILDREN, KNOWLEDGE AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY 12:00 – 12:30 BREAK 12:30 – 13:30 KEYNOTE Daniel Feldman (prerecorded presentation + Q&A) THE CHILD IN TIME: REFUGEE NARRATIVES IN CHILDREN'S BOOKS ABOUT THE 1938 – 39 KINDERTRANSPORT AND 2014 – 17 REFUGEE CRISIS 13:30 – 15:00 BREAK 15:00 – 16:00 SPEAKING THE UNSPEAKABLE: HOLOCAUST IN CHILDREN'S LITERATURE TRAUMA AND (POST) MEMORY – DISPLACEMENT AND 15:00 – 17:00 HISTORICAL AND PATRIOTIC SOCIALIZATION IN DISCUSSION PANEL RELATED TO PRERECORDED PRESENTATIONS (Chair: Elena MIGRATION (Chair: Isaac Willis Larison) LIVE PRESEN- LITERARY EDUCATION (Chair: Marina Balina) LIVE Mara Johnston): Eleanor Johnston (CA) Play and Peril: the Challenges of Ethical TATION Padma Venkatraman (US) The Bridge Home PRESENTATION: Zofia Zasacka: Civil and National Presentation of the Holocaust for Children in "Brundibar" and "The Magician COMBINED WITH DISCUSSION PANEL RELATED TO Values in Adolescents’ Reader Response; Emilya Ohar: of Auschwitz"; Jenna Marie D'Andrea (CA): As I Write You to Be: Enacting a PRERECORDED PRESENTATIONS: Aju Basil James From Myths to Reality: Transforming the Theme of War Pedagogy of Remembrance Through Holocaust Literature; Karen Krasny Where / Isaac Willis Larison: Trauma Versus Happiness: in Contemporary Ukrainian Literature for Children and the Breath Fails: Mourning and Mythic Time in Maurice Sendak‘s Dear Mili.; Irena The Transformation of Migration Stories in Children’s Adolescents; Dorota Michulka: „A Special Relationship”. -

Scarica Il Pdf!

Gianni rodari viaggio in italia MARI, MONTI, FIUMI… TITOLO TRATTO DAL LIBRO Adige (fiume) Il tenore proibito Il libro degli errori Adige (fiume) Un amore a Verona Il gioco dei quattro cantoni Alpe Quaggione Il ragioniere-pesce del Cusio Fra i banchi Alpe Quaggione C’era due volte il barone Lamberto Alpi Tutto il mondo in filastrocca Il secondo libro delle filastrocche Perché i settentrionali chiamano i Alpi Il libro dei perché meridionali col soprannome di «terroni»? Alpi Ferragosto Filastrocche in cielo e in terra Alpi L’Acca in fuga Il libro degli errori Alpi Il dottor Terribilis Tante storie per giocare Alpi Il tenore proibito Il libro degli errori Alpi Ciabattone e Fornaretto Il gioco dei quattro cantoni Alpi Cielo e terra Il gioco dei quattro cantoni Alpi Tutto cominciò con un coccodrillo Gip nel televisore e altre storie in orbita Alpi C’era due volte il barone Lamberto La guerra dei poeti (con molte rime in Alpi Cozie Novelle fatte a macchina «or») Appennini Ferragosto Filastrocche in cielo e in terra Appennini Gelsomino nel paese dei bugiardi Appennini C’era due volte il barone Lamberto Appennini Incontro con i maghi Il libro degli errori Appennino tosco-romagnolo La strega Il libro degli errori Basilicata La mia mucca Fra i banchi Belice (valle) Cielo e terra Il gioco dei quattro cantoni Biedano (torrente) L’affare del secolo Il gioco dei quattro cantoni Brianza Tanti bachi Il Pianeta degli alberi di Natale Calabria Perché l’Italia si chiama «Italia»? Il libro dei perché Crunch! Scrash! ovvero Arrivano i Calabria Novelle fatte a macchina Marziani Campagna Romana C’era due volte il barone Lamberto Campagne vicino a Roma L’anello del pastore Tante storie per giocare Campania Piccoli vagabondi Carso La torta in cielo Cassinate Piccoli vagabondi Catinaccio Il tenore proibito Il libro degli errori A cura di Arianna Tolin e David Tolin © 2018 Edizioni EL, via J. -

IL GIOVANE RODARI Di Pietro Macchione

Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 1 Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 2 PIETRO MACCHIONE EDITORE Via Salvo d’Acquisto, 2 - 21100 Varese Tel. 0332.499070 - Cell. 338.5337641 - Fax 0332.834126 E-mail: [email protected] Sito: www.macchionepietroeditore.it ISBN 978-88-6570-150-8 Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 3 Pietro Macchione STORIA DEL GIOVANE RODARI In collaborazione con Chiara Zangarini e Ambrogio Vaghi PIETRO MACCHIONE EDITORE Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 4 Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 5 INDICE Pag. 11 LO STUPORE DELLA VITA 11 La nascita 12 Giuseppe Rodari 16 Maddalena Aricocchi 20 Omegna e il Lago d’Orta 23 Scolaro e poeta 24 Il trasferimento a Gavirate 31 DIO E GLI UOMINI 31 Il Seminario 34 Studente in seminario 35 Lilium 38 L’uscita dal seminario 39 Ritorno a Gavirate 42 Prove di giornalismo 44 Propagandista di plaga e presidente del circolo san Luigi 48 Il pericolo comunista 54 Di nuovo il seminario, di nuovo Lilium 64 Studente a Varese 70 Iscritto alla G.I.L. 73 IL TRAVAGLIO SPIRITUALE di Chiara Zangarini 73 Lo scrittore 78 I primi racconti 84 Il timbro dello scrittore: alcune valutazioni 5 Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 6 Pag. 87 IL CAMBIAMENTO 87 Le amicizie dei sedici anni: una fucina di idee e cambiamenti 92 L’approssimarsi al comunismo 96 Mò a parlà in dialett 102 L’Università 104 Alfonso Gatto e Giorgio De Chirico 105 Il maestro 111 NUOVI STIMOLI di Chiara Zangarini 111 Breton e il Surrealismo 112 Gianni e la Fantastica 116 Il Quaderno di Fantastica 128 Ricetta per un racconto 129 La pianta delle pantofole 134 Alcune valutazioni 139 L’IMPEGNO IN PRIMA PERSONA 139 Prove di comunismo 142 Il partigiano 147 Impegno politico a Gavirate 148 “Cinque Punte” 151 Gavirate rimane centrale 151 Delegato al primo congresso varesino del PCI 152 Il Fronte della Gioventù 154 I lavori del congresso 154 Delegato al congresso nazionale 157 Membro della segreteria provinciale 158 “L’Ordine Nuovo” di Varese 159 Alfonso Gatto e Gianni a Varese 6 Libro Rodari.qxd 09/05/2013 4.12 Pagina 7 Pag. -

Propuesta De Lecturas Para Un Confinamiento

Propuesta de lecturas para un confinamiento Junio 2020 2 IMAGINANDO EL PRÓXIMO CURSO Cuando una madre cuenta un cuento, nieva; y la nieve cae sobre los ojos de los niños…; o llueve… aunque sea agosto. Walter Benjamin Juntos niñas y niños, madres y padres, maestras y maestros, con un mismo propósito, crecer. Imaginar la posibilidad de dejar atrás el tiempo de Cronos y pasar al tiempo de Kairós. Tiempo detenido, al amor de la lumbre, que madres y padres enciendan la lumbre de la mirada y la palabra…Había una vez…Érase una vez…y se encienda la llama de la Imaginación. A través de la palabra que calma, que arrulla, que calienta, que consuela. Y así comienza la aventura de oír, y desde mis Aquíes, desde el aquí, llegar al allí, pasando por el ahí. A través del relato, del gesto, del ritmo de la palabra del narrador. Al romperse la palabra de transmisión, el narrador de hoy necesita el apoyo y soporte de la palabra escrita. Elena Fortún nos acompaña y guía en el camino con su hermoso libro “El arte de contar cuentos”. PARA MADRES Y PADRES, MAESTRAS Y MAESTROS “Cuentos al amor de la lumbre “ A. Rodríguez Almodóvar, Ed. Anaya. “La aventura de oír“ Ana Pelegrín, Ed. Anaya. “El arte de contar cuentos” Elena Fortún, Ed. Renacimiento. “Poesía española para niños" Ana Pelegrín, Ed. Taurus. “Lo que sabía mi loro” José Moreno Villa, Ed. Visor. Para el nuevo curso, maestras y maestros abandonan el texto y se adentran en el 3 contexto, considerando que la niña y el niño es guardador perpetuo de la tradición folklórica, y que lo más valioso del hombre es lo que al cabo de los años queda de su vida infantil. -

Illustrators for Gianni Rodari. Italian Excellence 13‒15 November Booth 1A03

Illustrators for Gianni Rodari. Italian Excellence 13‒15 November Booth 1A03 (Hybrid Zone) The China Shanghai International Children’s Book Fair (CCBF) is glad to present Illustrators for Gianni Rodari. Italian Excellence, an art exhibition of 63 illustrations brought together to celebrate the centenary of one of Italy’s most revered writers, Gianni Rodari, born on October 23, 1920. Writer, teacher, journalist and poet, Rodari was one of the most innovative literary voices of the last century. Among the world’s best-loved and influential children’s authors, Gianni Rodari was the first Italian writer to receive—in 1970—the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award, generally considered the Nobel Prize for children’s literature. His work includes fairy stories, nursery rhymes, short stories and novels, as well as his famous essay La grammatica della fantasia, a seminal reference text for children’s literature and education specialists. Innovative, universal and still effortlessly topical, Rodari’s work has been translated and re-printed the world over. In China also, Rodari’s works are often seen as modern classics, especially Le avventure di Cipollino, which conquered generations of readers since it was first translated in 1953. Most importantly, Rodari’s work remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration for numerous Italian artists, who down the years have put his words into pictures. This exhibition looks at some of the artists who in the last fifty years have illustrated Rodari’s texts—starting with towering figures like Luzzati and Munari through to internationally renowned contemporary artists, including Alessandro Sanna, Beatrice Alemagna, Valerio Vidali and Gaia Stella. -

(Mildred L.) Batchelder Award Winners, 1968-Present

(Mildred L.) Batchelder Award winners, 1968-Present The most outstanding children’s book originally published in a language other than English in a country other than the United States, and subsequently translated into English for publication in the United States. 2021 Enchanted Lion Books, for Telephone Tales, written by Gianni Rodari, illustrated by Valerio Vidali and translated by Antony Shugaar. Honor: HarperAlley, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, for Catherine’s War, written by Julia Billet, illustrated by Claire Fauvel, and translated by Ivanka Hahnenberger. 2020 Enchanted Lion Books, for Brown, written by Håkon Øvreås, illus. by Øyvind Torseter, and translated by Kari Dickson. Honors: Godwin Books/Henry Holt/Macmillan, for The Beast Player, written by Nahoko Uehashi and translated by Cathy Hirano. Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster, for The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree, written by Paola Peretti, illustrated by Carolina Rabei and translated by Denise Muir. Enchanted Lion Books, for Do Fish Sleep?, written by Jens Raschke, illustrated by Jens Rassmus and translated by Belinda Cooper. Plough Publishing, for When Spring Comes to the DMZ, written and illustrated by Uk-Bae Lee and translated by Chungyon Won and Aileen Won. 2019 Thames & Hudson, Inc., for The Fox on the Swing, written by Evelina Daciūtė, illustrated by Aušra Kiudulaitė, and translated by The Translation Bureau Honors: NorthSouth Books, Inc., for Edison: The Mystery of the Missing Mouse Treasure, written and illustrated by Torben Kuhlmann, -

Summer Reading 2019 Copy

Summer Reading 2019 as recommended by The School Library The English Department The Department of Modern Foreign Languages St. George’s Students and Teachers Dear St. George’s Community, In our quest to nurture a culture of reading in our school, we have produced another wonderful list of books for you to enjoy this summer. Whether you are reading for work or pleasure, you will be able to do so in a range of languages, selecting from books recommended by our language faculties for all age groups. Titles in blue have recently been added to the school library and may be signed out during the academic year. The Magic of Reading Each story is a journey not only for the characters, but also for you. Books teach you compassion. They help you work on your capacity to connect to another person and invest yourself in their story. You will learn to be more observant, imaginative and creative. Reading can widen your mind’s horizons to an incredible extent and fully transform your view of the world. Books guide you towards becoming a dreamer and teach you that you are capable of doing anything you put your mind to, no matter how hard it may seem. The most important books in your life will be the ones that are mirrors of your life. You will see your own reflection in the pages and, as you read, you will start to understand yourself on a deeper level. Another part of you, that you have always been searching for, will be discovered. The words written by a complete stranger will help you connect with the person you have to know the best - yourself. -

Celebrating Dr. Seuss' 100Th Birthday • International Youth Library

cvr1.qxd 11/17/2003 11:55 AM Page 1 Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 1 Number 3 Winter 2003 ISSN 1542-9806 Celebrating Dr. Seuss’ 100th Birthday • International Youth Library • Caldecott Capers • Batchelder Award NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID BIRMINGHAM, AL PERMIT NO. 3020 wint03-CAL_final.qxd 02/02/2004 10:53 AM Page 1 Table Contentsl ofVolume 1, Number 3 Winter 2003 Notes and Letters 34 North to Canada 2 Editor’s Note ALA Annual Conference in Toronto, Ontario, June 2003 Sharon Korbeck Sharon Korbeck 2 Executive Director’s Note 36 Seeing the Light Malore I. Brown A Tribute to Ethel Macmillan and 3 Librarians Everywhere Letters to the Editor Brian Doyle Features 39 Dogs and Dinosaurs, 4 The Seussabilities Are Endless Hobbies and Horses Dr. Seuss Centennial Celebrations Age-Related Changes in Children’s Sharon Korbeck Information and Reading Preferences Brian W. Sturm 9 The Caldecott Capers Departments Good Books Make a Good Movie Megan Lynn Isaac 3 Call for Referees 52 Book Reviews 12 From Thieves to Hens 54 Index to Advertisers The 2003 Batchelder Award 55 ALSC News and Honor Books 61 Index to Volume 1 Sandra Imdieke and Monique leConge 64 The Last Word 15 Award Acceptance Speeches Batchelder Award Carnegie Medal 20 Imagination and Inspiration Hans Christian Andersen Award Nominees Lois Lowry and Vera B. Williams Ginny Moore Kruse 29 A Castle of Books Visiting the International Youth Library Susan Stan 33 Someday You’ll Go to the Moon page 4 Musings on Children’s Nonfiction Sharon Korbeck wint03-CAL_final.qxd 02/02/2004 10:53 AM Page 2 Editor’s Note What a Wubbulous Job! Sharon Korbeck I really love my job today; Editor It’s time to write and edit, I mean, play! Sharon Korbeck, Waupaca, WI Editorial Advisory Committee It’s the hundredth birthday of Dr. -

Hans Christian Andersen Awards Are the Highest International Distinction in Children’S Literature

HANS CH RISTIAN A NDERSEN A WARDS Christine E. King, Iowa State University The Hans Christian Andersen Awards are the highest international distinction in children’s literature. They are given every other year to a living author and illustrator whose outstanding body of work is judged to have made a lasting contribution to literature for children and young people. The first three awards were made to authors for single works. The author’s award has been given since 1956 and the illustrator’s since 1966. They are presented by the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY). They have become the “Little Nobel Prize,” and their prestige has grown over the years. Selecting the award win- ners is considered by many to be IBBY’s most important activity. The nominations are made by the National Sections of IBBY, and the recipients are selected by a distinguished international jury of children’s literature specialists. The IBBY emphasizes that the Hans Christian Andersen Awards are not intended to be a national award, but an outstanding international award for chil- dren’s literature. A great effort is made to encourage the submission of candidates from all over the world, and a jury of ten experts is also selected from around the world in order to encourage a diversity of outlook and opinion. The award consists of a gold medal bearing the portrait of Hans Christian Andersen and a diploma and is presented at the opening ceremony of the IBBY Congress. The IBBY’s refereed journal Bookbird has a special Andersen Awards issue which presents all the nominees and documents the selection process. -

Discovering What's New in Tourism in 2021

Discovering what's new in tourism in 2021 Lake Maggiore, Lake Orta, Lake Mergozzo, Ossola Valleys. A microcosm of emotions waiting to be explored! Start of the 2021 tourist season The romantic atmosphere of the lakes, the grandeur of the mountains, CONTACT the outdoor and wellness experiences and the excellence of food and wine. Distretto Turistico dei Laghi Corso Italia, 26 The Tourist District of the Mountains, Lakes and Valleys in northern 28838 Stresa (VB) Piedmont, just a stone's throw from the Swiss border and the cities of Milan and Turin, is the ideal destination for a quality, relaxing stay. Italia From the famous Lake Maggiore with the enchanting Borromean Islands, to the clear waters of the tranquil Lake Mergozzo , to the enchanting scenery of Lake Orta with the charming Island of San Giulio: Ph. +39 0323 30416 one of the most beautiful destinations in the world. [email protected] All around, the Ossola Valleys offer to mountain lovers vast expanses of woodland, small alpine lakes, high peaks and spectacular parks, www.distrettolaghi.it including Monte Rosa, Val Grande National Park, Alpe Veglia-Devero and www.lagomaggiorexperience.it Alta Valle Antrona Nature Parks. And let's not forget our fantastic towns and villages that have been awarded the prestigious Orange Flags (by the Italian Touring Club to Arona, Cannero, Cannobio, Macugnaga, Malesco, Mergozzo, Santa Maria Maggiore, Orta San Giulio and Vogogna) and the Blue Flags awarded to the seaside resorts of Arona, Cannero, Cannobio and Gozzano, the only places in the whole of Piedmont to receive this important recognition. -

Was Wäre, Wenn… 2020

Was wäre, wenn… wir eine Brücke zwischen Bayern und dem Piemont schlagen würden? 2020 Der Katalog enthält Textbeiträge der Autoren, Informationen zu den Gästen sowie das Programm anlässlich des 100. Geburtstags von Gianni Rodari, das von Januar bis Juni 2020 in Bayern und am Ortasee im Piemont stattfindet. Illustration von Mauro Maulini München - Ingolstadt - Ortasee Gianni Rodari 1 Gianni Rodari wurde am 23. Oktober 1920 in Omegna am Ortasee geboren. Nach seinem Pädagogik-Studium begann er, an einer Grundschule zu unterrichten. Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs war er im Widerstand tätig und 1944 wurde er Mitglied in der Kommunistischen Partei Italiens. Nach der Befreiung schlug er eine journalistische Karriere ein, zuerst in Mailand und danach in Rom, wo er sich 1950 auch niederließ. Er hat für zahlreiche Zeitschriften gearbeitet, z.B. für „L‘Unità“, „Paese Sera“, den „Pioniere“, „Avanguardia“. 1953 heiratete er Maria Teresa Ferretti und einige Jahre danach wurde seine Tochter Paola geboren. In jenen Jahren begann er für Kinder zu schreiben und veröffentlichte – meistens bei Editori Riuniti und Einaudi - einige seiner bekanntesten Werke. Seine Bücher wurden sowohl von den Lesern als auch von den Kritikern begeistert aufgenommen. 1970 erhielt er die höchste Auszeichnung, die es für Kinderliteratur gibt, nämlich die Hans-Christian-Andersen- Medaille. Im Jahr 1973 veröffentlichte Rodari sein pädagogisches Meisterwerk: Die Grammatik der Phantasie, die heute noch gültige Reflexionen zur Rolle der Kreativität und Vorstellungskraft im erzieherischen Prozess anbietet. In den Siebziger Jahren hat er an zahlreichen Begegnungen mit Erziehern, Lehrern und Schülern in Italien wie auch in der Sowjetunion, die er mehrere Male bereiste, teilgenommen. Für Kinder schrieb er Reime, Gedichte, Fabeln und Romane, die zu Klassikern in der Kinderliteratur wurden, wie z.B. -

Premios Andersen De Literatura Antonio Orlando Rodríguez /Adaptación Bárbara Streeter

Premios Andersen de Literatura Antonio Orlando Rodríguez /Adaptación Bárbara Streeter Para hablar sobre los Premios Andersen hay que referirse primero a IBBY. IBBY son las siglas que identifican a la Organización Internacional para el Libro Juvenil. Esta entidad fue fundada en Zurich, Suiza, en 1953. IBBY está integrada por alrededor de 60 secciones en diferentes países de todos los continentes y agrupa a personas comprometidas con una idea común: el encuentro de los libros y los niños. IBBY tiene entre sus propósitos principales: o Promover el entendimiento internacional a través de los libros para niños y jóvenes. o Favorecer en todo el mundo que los niños tengan acceso a libros de gran calidad literaria y artística. o Favorecer la publicación y la distribución de libros de calidad para niños y jóvenes, especialmente en los países en desarrollo. o Apoyar y formar a quienes trabajan con niños y jóvenes y con la literatura para niños. o Estimular la investigación y el trabajo académico en el campo de la literatura para niños. IBBY surgió como resultado del empeño de Jella Lepman, una alemana convencida de la importancia de los libros para niños. Finalizada la segunda guerra mundial, esta mujer comenzó a trabajar para que todas aquellas personas del mundo involucradas en la creación, selección y distribución de libros para niños - autores, ilustradores, bibliotecarios, profesores, editores, libreros, etc.- se agruparan en una organización que les permitiera conocerse y trabajar juntos. Así nació IBBY, en 1953. Y a los tres años de vida, también por iniciativa de Jella Lepman, IBBY instituyó un galardón bienal dedicado a premiar a los creadores de libros para niños: la Medalla Hans Christian Andersen.