Cinematography, Post-Production, and Digital Colour. Jacques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toland Asc Digital Assistant

TOLAND ASC DIGITAL ASSISTANT PAINTING WITH LIGHT or more than 70 years, the American Cinematographer Manual has been the key technical resource for cinematographers around the world. Chemical Wed- ding is proud to be partners with the American Society of Cinematographers in bringing you Toland ASC Digital Assistant for the iPhone or iPod Touch. FCinematography is a strange and wonderful craft that combines cutting-edge technology, skill and the management of both time and personnel. Its practitioners “paint” with light whilst juggling some pretty challenging logistics. We think it fitting to dedicate this application to Gregg Toland, ASC, whose work on such classic films as Citizen Kane revolutionized the craft of cinematography. While not every aspect of the ASC Manual is included in Toland, it is designed to give solutions to most of cinematography’s technical challenges. This application is not meant to replace the ASC Manual, but rather serve as a companion to it. We strongly encourage you to refer to the manual for a rich and complete understanding of cin- ematography techniques. The formulae that are the backbone of this application can be found within the ASC Manual. The camera and lens data have largely been taken from manufacturers’ speci- fications and field-tested where possible. While every effort has been made to perfect this application, Chemical Wedding and the ASC offer Toland on an “as is” basis; we cannot guarantee that Toland will be infallible. That said, Toland has been rigorously tested by some extremely exacting individuals and we are confident of its accuracy. Since many issues related to cinematography are highly subjective, especially with re- gard to Depth of Field and HMI “flicker” speeds, the results Toland provides are based upon idealized scenarios. -

List of Sunlight Media Collective Members & Board Sunlight Media

List of Sunlight Media Collective Members & Board Sunlight Media Collective Core Leadership Bios • Dawn Neptune Adams (Penobscot Tribal Member, Racial Justice Consultant to the Peace + Justice Center of Eastern Maine, Wabanaki liaison to Maine Green Independent Party Steering Committee + environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Dawn is a Sunlight Media Collective content advisor, journalist, public speaker, narrator, production assistant, grant writer + event organizer. • Maria Girouard (Penobscot Tribal Member, Historian focused on Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Act, Coordinator of Wabanaki Health + Wellness at Maine- Wabanaki REACH + environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Maria is a Sunlight Media Collective co-founder, film director, writer, content advisor, public speaker + event organizer. • Meredith DeFrancesco (Radio Journalist of RadioActive on WERU, environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Meredith is a Sunlight Media Collective co- founder, film producer, film director, journalist, organizational & financial management person + event organizer. • Sherri Mitchell (Penobscot Tribal Member, lawyer, environmental & Indigenous rights activist, author, and Director of Land Peace Foundation). Sherri is a Sunlight Media Collective content advisor, writer, grant writer, public speaker + event organizer. • Josh Woodbury (Penobscot Tribal Member, Tribal IT Department and Cultural & Historic Preservation Department, + Filmmaker). Josh is a Sunlight Media Collective cinematographer, film editor, web designer + content -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

Cinematographer As Storyteller How Cinematography Conveys the Narration and the Field of Narrativity Into a Film by Employing the Cinematographic Techniques

Cinematographer as Storyteller How cinematography conveys the narration and the field of narrativity into a film by employing the cinematographic techniques. Author: Babak Jani. BA Master of Philosophy (Mphil): Art and Design University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Swansea October 2015 Revised January 2017 Director of Studies: Dr. Paul Jeff Supervisor: Dr. Robert Shail This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of a MPhil in the Faculty of Art and Design to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Cinematographer as Storyteller How cinematography conveys the narration and the field of narrativity into a film by employing the cinematographic techniques. Author: Babak Jani. BA Master of Philosophy (Mphil): Art and Design University of Wales Trinity Saint David. Swansea October 2015 Revised January 2017 Director of Studies: Dr. Paul Jeff Supervisor: Dr. Robert Shail This research was undertaken under the auspices of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David and was submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of a MPhil in the Faculty of Art and Design to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David. This page intentionally left blank. 4 The alteration Note: The alteration of my MPhil thesis has been done as was asked for during the viva for “Cinematographer as Storyteller: How cinematography conveys narration and a field of narrativity into a film by employing cinematographic techniques.” The revised thesis contains the following. 1- The thesis structure had been altered to conform more to an academic structure as has been asked for by the examiners. -

Cinematography

CINEMATOGRAPHY ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS • The filmmaker controls the cinematographic qualities of the shot – not only what is filmed but also how it is filmed • Cinematographic qualities involve three factors: 1. the photographic aspects of the shot 2. the framing of the shot 3. the duration of the shot In other words, cinematography is affected by choices in: 1. Photographic aspects of the shot 2. Framing 3. Duration of the shot 1. Photographic image • The study of the photographic image includes: A. Range of tonalities B. Speed of motion C. Perspective 1.A: Tonalities of the photographic image The range of tonalities include: I. Contrast – black & white; color It can be controlled with lighting, filters, film stock, laboratory processing, postproduction II. Exposure – how much light passes through the camera lens Image too dark, underexposed; or too bright, overexposed Exposure can be controlled with filters 1.A. Tonality - cont Tonality can be changed after filming: Tinting – dipping developed film in dye Dark areas remain black & gray; light areas pick up color Toning - dipping during developing of positive print Dark areas colored light area; white/faintly colored 1.A. Tonality - cont • Photochemically – based filmmaking can have the tonality fixed. Done by color timer or grader in the laboratory • Digital grading used today. A scanner converts film to digital files, creating a digital intermediate (DI). DI is adjusted with software and scanned back onto negative 1.B.: Speed of motion • Depends on the relation between the rate at which -

Duties of a Cinematographer in Creating a Film

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2016, Vol. 6, No. 7, 824-827 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.07.013 D DAVID PUBLISHING Duties of a Cinematographer in Creating a Film Ikboljon Melikuziev State Institute of Arts and Culture, Tashkent, Uzbekistan The present article deals with the duties, role and methodical peculiarities of a cinematographer in creating a feature film. The development of creating artistic works in the high creative level and its process is comparatively analyzed within the progress of the Uzbek cinematography. Keywords: cinematographer, film director, critic, image, lightness, recurs, production, picture, plastics, rhythm, composition, editing, scenario, method Introduction The art of cinematography has not been studied widely. It is very difficult to express the description of a film by words. One must see the picture and just for this case a cinematographer’s artistic activity of many years needs careful study. They say, it is not written much about a cameraman’s work yet. In our opinion, the essence of their creativity involves expressing the method, plastics and descriptive decision of a ready feature film. The film supposedly is connected only with the name of a director as a single filmmaker. While criticizing a film they usually speak just about a director and leading actors. You can hardly find anything about a cameraman’s work. Naturally, it is not enough. However, a cameraman’s work spent for artistic picture demands a serious analyses and careful study. Undoubtedly, the right stylistics, artistically completeness of the form which strengthens the effective power of a feature film and accepting the film by the audience depends on the cinematographer’s skills. -

Basics of Cinematography HCID 521

University of Washington Basics of Cinematography HCID 521 January 2015 Justin Hamacher University of Washington Cinematography Basics INTRODUCTION 2 Justin Hamacher Overview University of Washington 30% SENIOR ON-SHORE 3 Justin Hamacher University of Washington Cinematography Principles Storyboarding 4 Justin Hamacher University of Washington Cinematography Principles 5 Justin Hamacher University of Washington Planes of the Image • Background = part of the image that is the furthest distance from the camera • Middle ground = midpoint within the image • Foreground = part of the image that is the closest to the camera Justin Hamacher University of Washington Framing Framing = using the borders of the cinematic image (the film frame) to select and compose what is visible onscreen In filming, the frame is formed by the viewfinder on the camera In projection, it is formed by the screen Justin Hamacher University of Washington Cropping Cropping refers to the removal of the outer parts of an image to improve framing, accentuate subject matter or change aspect ratio. Justin Hamacher University of Washington Framing: Camera Height Relative height of the camera in relation to eye-level At eye level Below eye level Justin Hamacher University of Washington Framing: Camera Level The camera’s relative horizontal position in relation to the horizon • Parallel to horizon • Canted framing Justin Hamacher University of Washington Framing: Camera Angle Vantage point imposed on image by camera’s position Straight-On High Angle Low Angle Justin Hamacher University of Washington Speed of Motion Rate at which images are recorded and projected The standard frame rate for movies is 24 frames per second Filming at higher rate (>24 fps) results in motion appearing slowed-down when projected at 24 fps Filming at a lower rate (<24 fps) results in motion appearing sped-up when projected at 24 fps. -

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies

Choosing Between Communication Studies and Film Studies Many students with an interest in media arts come to UNCW. They often struggle with whether to major in Communication Studies (COM) or Film Studies (FST). This brief position statement is designed to help in that decision. Common Ground Both programs have at least three things in common. First, they share a common set of technologies and software. Both shoot projects in digital video. Both use Adobe Creative Suite for manipulation of digital images, in particular, Adobe Premiere for video editing. Second, they both address the genre of documentaries. Documentaries blend the interests of both “news” and “narrative” in compelling ways and consequently are of interest to both departments. Finally, both departments are “studies” departments: Communication Studies and Film Studies. Those labels indicate that issues such as history, criticism and theories matter and form the context for the study of any particular skills. Neither department is attempting to compete with Full Sail or other technical training institutes. Critical thinking and application of theory to practice are critical to success in FST and COM. Communication Studies The primary purposes for the majority of video projects are to inform and persuade. Creativity and artistry are encouraged within a wide variety of client- centered and audience-centered production genres. With rare exception, projects are approached with the goal of local or regional broadcast. Many projects are service learning oriented such as creating productions for area non-profit organizations. Students will create public service announcements (PSA), news and sports programming, interview and entertainment prog- rams, training videos, short form documentaries and informational and promotional videos. -

Elegies to Cinematography: the Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars Jamie Clarke Southampton Solent University

CHAPTER SEVEN Elegies to Cinematography: The Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars Jamie Clarke Southampton Solent University Introduction In 2013, the magazine Blouinartinfo.com interviewed Christopher Doyle, the firebrand cinematographer renowned for his lusciously visualised collaborations with Wong Kar Wai. Asked about the recent award of the best cinematography Oscar to Claudio Miranda’s work on Life of Pi (2012), Doyle’s response indicates that the idea of collegiate collaboration within the cinematographic community might have been overstated. Here is Doyle: Okay. I’m trying to work out how to say this most politely … I’m sure he’s a wonderful guy … but since 97 per cent of the film is not under his control, what the fuck are you talking about cinematography ... I think it’s a fucking insult to cinematography … The award is given to the technicians … it’s not to the cinematographer … If it were me … How to cite this book chapter: Clarke, J. 2017. Elegies to Cinematography: The Digital Workflow, Digital Naturalism and Recent Best Cinematography Oscars. In: Graham, J. and Gandini, A. (eds.). Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries. Pp. 105–123. London: University of Westminster Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/book4.g. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 106 Collaborative Production in the Creative Industries I wouldn’t even turn up. Because sorry, cinematography? Really? (Cited in Gaskin, 2013) Irrespective of the technicolor language, Doyle’s position appeals to a tradi- tional and romantic view of cinematography. This position views the look of film as conceived in the exclusive monogamy the cinematographer has histori- cally enjoyed on-set with the director during principal photography. -

Module Title Introduction to Cinematography

Module Title Introduction to Cinematography (New) Programme(s)/Course Film Practice Level 5 Semester 1 Ref No: Credit Value 20 CAT Points Student Study hours Contact hours: 48 Student managed learning hours: 152 Pre-requisite learning None Co-requisites None Excluded None combinations Module Coordinator TBA Parent School Division of Film and Media, School of Arts & Creative Industries Parent Course Film Practice Description This Module provides both skills-based training in the use of High Definition (HD) cameras as well as the opportunity to study the techniques and aesthetics of cinematography. Students will be exposed to the particular demands and possibilities of working with High Definition cameras and editing workflows, and will be asked to shoot scenes according to specified aesthetic and dramatic criteria. Students will be encouraged to work from their own scripts as developed in the adjacent filmmaking workshops, thereby creating a system of feedback where learning outcomes in one part of the course feed into another. Aims The aims of this Module are to: Train students to work proficiently with HD cameras. Introduce students to methods for managing and editing HD video resources. Develop students’ ability to manipulate cameras to achieve specific stylistic and dramatic effects. Introduce students to the standards, practices and techniques of HD cinematography Learning outcomes On successful completion of this module students will be able to: Knowledge and Understanding 1. Work with a range of Digital Cinema Cameras to capture appropriately exposed, focused and colour balanced images. Intellectual Skills 2. Translate ideas into shot-sequences. 3. Translate internal states into visible action in effectively composed images. -

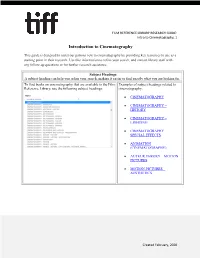

Introduction to Cinematography

FILM REFERENCE LIBRARY RESEARCH GUIDE: Intro to Cinematography, 1 Introduction to Cinematography This guide is designed to assist our patrons new to cinematography by providing key resources to use as a starting point in their research. Use this information to refine your search, and contact library staff with any follow-up questions or for further research assistance. Subject Headings A subject heading can help you refine your search, making it easier to find exactly what you are looking for. To find books on cinematography that are available in the Film Examples of subject headings related to Reference Library, use the following subject headings: cinematography: CINEMATOGRAPHY CINEMATOGRAPHY – HISTORY CINEMATOGRAPHY – LIGHTING CINEMATOGRAPHY – SPECIAL EFFECTS ANIMATION (CINEMATOGRAPHY) AUTEUR THEORY – MOTION PICTURES MOTION PICTURES – AESTHETICS Created February, 2020 FILM REFERENCE LIBRARY RESEARCH GUIDE: Intro to Cinematography, 2 Recommended Books Books provide a comprehensive overview of a larger topic, making them an excellent resource to start your research with. Chromatic cinema : a history of screen color by Richard Misek. Publisher: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010 Cinematography : theory and practice : imagemaking for cinematographers and directors by Blain Brown. Publisher: Routledge, 2016 Digital compositing for film and video : production workflows and techniques by Steve Wright. Publisher: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018 Every frame a Rembrandt : art and practice of cinematography by Andrew Laszlo. Publisher: Focal Press, 2000 Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir by Patrick Keating. Publisher: Columbia University Press, 2010 The aesthetics and psychology of the cinema by Jean Mitry. Publisher: Indiana State University Press, 1997 The art of the cinematographer : a survey and interviews with five masters by Leonard Martin. -

Cinematography in the Piano

Cinematography in The Piano Amber Inman, Alex Emry, and Phil Harty The Argument • Through Campion’s use of cinematography, the viewer is able to closely follow the mental processes of Ada as she decides to throw her piano overboard and give up the old life associated with it for a new one. The viewer is also able to distinctly see Ada’s plan change to include throwing herself in with the piano, and then her will choosing life. The Clip [Click image or blue dot to play clip] The Argument • Through Campion’s use of cinematography, the viewer is able to closely follow the mental processes of Ada as she decides to throw her piano overboard and give up the old life associated with it for a new one. The viewer is also able to distinctly see her plan change to include throwing herself in with the piano, and then her will choosing life. Tilt Shot • Flora is framed between Ada and Baines – She, being the middle man in their conversations, is centered between them, and the selective focus brings our attention to this relationship. • Tilt down to close up of hands meeting – This tilt shows that although Flora interprets for them, there is a nonverbal relationship that exists outside of the need for her translation. • Cut to Ada signing – This mid-range shot allows the viewer to see Ada’s quick break from Baines’ hand to issue the order to throw the piano overboard. The speed with which Ada breaks away shows that this was a planned event. Tilt Shot [Click image or blue dot to play clip] Close-up of Oars • Motif – The oars and accompanying chants serve as a motif within this scene.