Otto Piene (1928–2014) 46 Karen E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J Jumpsuit Course Information & Syllabus 1

ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES: CHICAGO, ILL. / LOS ANGELES, CALIF. / WWW.JUMPSU.IT JUMPSUIT J COURSE INFORMATION & SYLLABUS DOCUMENT: RDS . JUMPSUIT How to Make a Personal Uniform for the End of Capitalism COURSE DESCRIPTION Fashion is inherently political. We see this in the way our clothing produces social signals to ways it is bought, sold, worn, and produced. In this six-week class the Rational Dress Society, in collaboration with the Arts Research Collective (ARC), will position fashion in the context of theory and practice. Students will learn to sew a JUMPSUIT of their very own alongside lessons and discussions on topics including, Marxism, feminism, cyborgs, revolutionary dress, the environment, labor and the end of western capitalism. June 17th - July 26th Wednesday/Sunday 8:00 - 9:30 est WHAT IS THIS COURSE ABOUT? This course will be structured in two parts. In the first half, we will learn to sew JUMPSUITS using a free pattern designed by the RDS. In the second half, we will learn to design our own personal uniform, to replace all clothes in perpetuity. Alongside sewing, patternmaking and design demonstrations, RDS cofounders Abigail Glaum-Lathbury and Maura Brewer will lead a series of discussions and workshops to reimagine what a post-consumer society might look like. Together, we will turn theory into practice and form new bonds of solidarity in times of self-isolation. WHAT WILL STUDENTS LEARN? This class is designed for any individual who would like to make a JUMPSUIT regardless of prior sewing experience. Together with online workshops, supplemental instructional videos and resources, students will create a RDS monogarment from start to finish while discussing the historical and theoretical framework of our current political landscape. -

Passion and Glory! Spectacular $Nale to National Series

01 Cover_DC_SKC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 22/9/14 14:25 Page 1 AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Fields of victory At home and abroad Fun as future stars shine Medals galore! Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery 03 Contents_KC_V2_APP:Archery 2012 24/9/14 11:44 Page 3 CONTENTS 3 Welcome to 0 PICTURE: COVER: AUTUMN 2014 £4.95 Larry Godfrey wins National Series gold Dean Alberga Passion and glory! Spectacular $nale to National Series Wow,what a summer! It’s been non-stop.And if the number of stories received over the past few Fields of victory weeks is anything to go by,it looks like it’s been the At home and abroad same for all of us! Because of that, some stories and regular features Fun as future have been held over until the next issue – but don’t stars shine Medals galore! worry,they will be back. Longbow G Talent Festival G VI archery So what do we have in this issue? There is full coverage of the Nottingham Building Society Cover Story National Series Grand Finals at Wollaton Hall, including exclusive interviews with Paralympians John 40 Nottingham Building Society National Series Finals Stubbs and Matt Stutzman.And, as many of our young archers head off to university,we take a look at their options. We have important – and possibly unexpected – news for tournament Features organisers, plus details about Archery GB’s new Nominations Committee. 34 Big Weekend There have been some fantastic results at every level, both at home and abroad.We have full coverage of domestic successes as well the hoard of 38 Field Archery international medals won by our 2eld, para and Performance archers. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Homewear & Home Sportswear Fall Winter 2021

HOMEWEAR & HOME SPORTSWEAR FALL WINTER 2021 Winter Wonderland A visit to Chateau Pippadour is an experience not easily forgotten. I remember everything as if it were yesterday: the lavish floral wallpaper in the guest room, the carpet & the paintings. Jack and Pippadour taught me to enjoy – my family, my friends, the here and now. very November, Pippadour prepared the cas- and print on my new jumpsuit are so wonderful that tle for the upcoming winter. There was to be I can wear it in town – and I’m even considering wearing no more gardening until spring. And since she it for Christmas dinner. would be indoors much more in winter, she brought the outdoors in. She hung extra cur- Now that the outdoor season is coming to an end, I’m Etains in front of the bedroom windows. And the down spending a lot more time in the kitchen. I’m making mash duvets were covered in sheets in the colours of the pots and stews. And, in the afternoon, I’m enjoying roast- garden and woods, featuring the same patterns as her ed chestnuts, baked pears with cinnamon and apple pie wallpaper as well as cranes. Pippadour admired cranes with nuts. So my home smells just as festive as it looks. for their strength and grace. And especially their legend: I’ve now also found the perfect recipe for crème brûlée. fold a thousand paper cranes and your heart’s desire will In my brand-new sports outfit, I manage to find the right come true. In a nutshell, cranes were her lucky charms. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Open Gardens2016

THE HARDY PLANT SOCIETY OF OREGON OPEN GARDENS2016 gardeners growing together Garden Thyme Nursery Harvest Nursery Hydrangeas Plus Nowlens Bridge Perennials Out in the Garden Nursery Sebright Gardens Secret Garden Growers Bailey garden 2016 Open Garden season is about to begin! Welcome to this year’s directory of approximately 100 listings covering a wide variety of wonderful gardens and nurseries to visit all season. Many gardens will be open on the weekends, and evening openings are on the second and fourth Mondays of June, July, August and September. The Directory has been prepared by a dedicated committee led by Chair Tom Barreto, assisted by Ruth Clark, Merle Dole-Reid, Jenn Ferrante, Barry Gates, Jim Rondone, Pam Skalicky, Lise Storc and Bruce Wakefield. Tom is also much appreciated for his beautiful photography which graces the cover this year. Special thanks to Linda Wisner for cover design, advice and production direction and a very big thank you to Bruce Wakefield for his help with a process that is always time consuming; we are very grateful. We have worked hard to assure the accuracy of the listings in the 2016 Open Gardens Directory, but if you find an error or omission, please contact the HPSO office at 503-224-5718. Corrections will be announced in the HPSO weekly email blasts. And most importantly, our deepest thanks to the generous and welcoming HPSO members who are sharing their gardens this year. We appreciate the opportunity to learn from, and enjoy, your remarkable gardens. 1 VISITOR GUIDELINES TO GOOD GARDEN ETIQUETTE We are fortunate to be able to visit so many glorious gardens through our HPSO membership. -

Zen Bow Article: the Bodhisattvic Garden

Zen Bow Article: The Bodhisattvic Garden (After the zendo, the Zen Center's back garden is an ideal place for contemplation. It remains a still point in the middle of an inner-city neighborhood, and when I need to begin a letter, or to make some notes on the changing seasons, I find myself drawn to its domain.) Today, having nothing to write down, I leave my notebook open on one of the tables. As the pages flutter in a light breeze, the white paper with its thin blue lines absorbs the chattering of nearby sparrows, the scuttling of a squirrel as it spirals down a tree trunk, the flickering of someone walking briskly behind a fence. High up in the late afternoon sky, the vapor-trail of a plane, reflecting the earth, becomes more elongated and curved as it stretches towards the horizon. The following evening, the neighbor's calico cat presses her nose against the screen door and stares across the kitchen foyer into the twilight of the zendo. Like a person admiring a painting by Vermeer, she studies the receding aisle of shadowy figures who are sitting in perfect stillness on their brown cushions. Then a bell is struck to end the round of meditation, and she disappears down the back steps, her own bell tinkling faintly as she runs across the lawn. * * * The leaves are whispering to each other in a light and steady rain. Summer is now well-established, and the covering of myrtle under the locust tree is a deep shade of green. Beyond the myrtle, a dogwood is in full bloom, its white, four-leafed flowers resembling clusters of child-like stars. -

James Tate - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Tate - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Tate(8 December 1943 -) James Tate is an American poet whose work has earned him the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. <b>Early Life</b> James Vincent Tate was born in Kansas City, Missouri. He received his B.A. from Kansas State University in 1965 and then went on to earn his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa in their famed Writer's Workshop. <b>Career</b> Tate has taught creative writing at the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University. He currently teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where he has worked since 1971. He is a member of the poetry faculty at the MFA Program for Poets & Writers, along with Dara Wier and Peter Gizzi. Dudley Fitts selected Tate's first book of poems, The Lost Pilot (1967) for the Yale Series of Younger Poets while Tate was still a student at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop; Fitts praised Tate's writing for its "natural grace." Despite the early praise he received Tate alienated some of his fans in the seventies with a series of poetry collections that grew more and more strange. He has published two books of prose, Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee (2001) and The Route as Briefed (1999). His awards include a National Institute of Arts and Letters Award, the Wallace Stevens Award, a Pulitzer Prize in poetry, a National Book Award, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Summerfest 2013 Brings Just What the Doctors Ordered Starting Saturday, August 3, at 10 AM, with 3 Steps to Incredible Health with Dr

08/2013 Love, Laugh & Eat with John Tickell, MD—Live! • Masterpiece MYSTERY: Silk • The March SummerFest Enjoy sensational specials and tell your friends. Sarah Brightman: Dreamchaser in Concert Live! at UNC-TV Love, Laugh Alfie Boe: & Eat with Storyteller at the John Tickell, MD Royal Albert Hall The Supremes: ‘60s Girl Grooves Elvis: Aloha From Hawaii An Evening with Doc Watson & David Holt Please help us find new members to sustain UNC-TV’s life-changing television! AugustCP.indd 1 7/17/13 1:21 PM augustHIGHLIGHTS On ... SummerBeat the Heat with Cool Fest Specials! SummerFest 2013 brings just what the doctors ordered starting Saturday, August 3, at 10 AM, with 3 Steps to Incredible Health with Dr. Joel Fuhrman and Healthy Hormones: Brain Body Fitness, at noon. Keep moving with toe-tapping tunes from ‘60s Pop, Rock & Soul, at 1 PM, and Doobie Brothers Live at Wolf Trap, at 3 PM. Then, at 4:30 PM, learn to Love, Laugh & Eat with John Tickell, MD—LIVE—in the UNC-TV studio! Stroll down memory lane with Lawrence Welk: Precious Memories, at 6 PM, and pick up the tempo with ‘60s Girl Grooves, at 8 PM. Saturday takes a dramatic turn with the last new episode of the hit Brit mystery series Death in Paradise, at 10 PM. Get inspired Sunday, August 4, with Smarter Brains, at 10 AM, and George Beverly Shea: The Wonder of It All, at 11:30 AM. Enjoy The Great American Songbook, at 1 PM, Hugh Laurie—Live on the Queen Mary, at 3 PM, and Superstars of Seventies Soul Live, at 4 PM. -

Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2)

Harvard Library bibliography: Supplement (Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Carpenter, Kenneth E. 1996. Harvard Library bibliography: Supplement (Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 6.2). Harvard Library Bulletin 6 (2), Summer 1995: 57-64. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42665395 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 57 Harvard Library Bibliography: Supplement his is a list of selected new books and articles of which any unit of the Harvard T University Library is the author, primary editor, publisher, or subject. The list also includes scholarly and professional publications by Library staff. The bibli- ography for 1960-1966 appeared in the Harvard Library Bulletin, 15 (1967), and supplements have appeared in the years following, most recently in Vol. 3 (New Series), No. 4 (Winter 1992-1993). The list below covers publications through mid-1995. Alligood, Elaine. "The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine: Poised for the Future, Guided by the Past," in Network News, the quarterly publication of the Massachu- setts Health Sciences Library Network (August 1994). (Elaine Alligood was formerly Assistant Director for Marketing in the Countway Library of Medicine.) Altenberger, Alicja and John W. Collins III. "Methods oflnstruction in Management for Libraries and Information Centers" in New Trends in Education and Research in Librarianshipand InformationScience (Poland:Jagiellonian University, 1993), ed. -

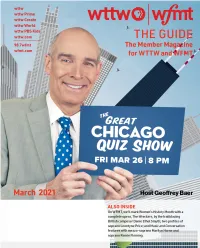

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 08/19/2010 11:24 Am

Playlist - WNCU ( 90.7 FM ) North Carolina Central University Generated : 08/19/2010 11:24 am WNCU 90.7 FM Format: Jazz North Carolina Central University (Raleigh - Durham, NC) This Period (TP) = 08/12/2010 to 08/18/2010 Last Period (TP) = 08/05/2010 to 08/11/2010 TP LP Artist Album Label Album TP LP +/- Rank Rank Year Plays Plays 1 1 Kenny Burrell Be Yourself HighNote 2010 15 15 0 1 39 Tomas Janzon Experiences Changes 2010 15 2 13 3 2 Curtis Fuller I Will Tell Her Capri 2010 13 11 2 3 23 Chris Massey Vibrainium Self-Released 2010 13 3 10 5 3 Lois Deloatch Roots: Jazz, Blues, Spirituals Self-Released 2010 10 10 0 5 9 Buselli Wallarab Jazz Mezzanine Owl Studios 2010 10 5 5 Orchestra 7 16 Mark Weinstein Timbasa Jazzheads 2010 8 4 4 7 71 Amina Figarova Sketches Munich 2010 8 1 7 7 71 Steve Davis Images Posi-Tone 2010 8 1 7 10 5 Nnenna Freelon Homefree Concord 2010 7 8 -1 10 9 Fred Hersch Whirl Palmetto 2010 7 5 2 12 5 Tim Warfield A Sentimental Journey Criss Cross 2010 6 8 -2 12 8 Rita Edmond A Glance At Destiny T.O.T.I. 2010 6 6 0 12 16 Eric Reed & Cyrus Chestnut Plenty Swing, Plenty Soul Savant 2010 6 4 2 12 23 The Craig Russo Latin Jazz Mambo Influenciado Cagoots 2010 6 3 3 Project 12 39 Radam Schwartz Songs For The Soul Arabesque 2010 6 2 4 12 71 Tamir Hendelman Destinations Resonance 2010 6 1 5 12 267 Buckwheat Zydeco Lay Your Burden Down Alligator 2009 6 0 6 12 267 Charlie Musselwhite The Well Alligator 2010 6 0 6 20 4 Jason Moran Ten Blue Note 2010 5 9 -4 20 7 Stephen Anderson Nation Degeneration Summit 2010 5 7 -2 20 16 Keith Jarrett