Composer, Poet and Philosopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Cyril Scott (1879 - 1970)

SRCD.365 STEREO/UHJ DDD The songs of Cyril Scott (1879 - 1970) 1 Pierrot and the Moon Maiden (1912) Dowson 3.01 2 Daffodils Op. 68 No. 1 (1909) Erskine 1.57 3 Spring Song (1913) C Scott 2.33 The songs of 4 Don't Come in Sir, Please! Op. 43 No. 2 (1905) trans. Giles 2.15 5 Willows Op. 24 No. 2 (1903) C Scott 2.21 Cyril Scott 6 In a Fairy Boat Op. 61 No. 2 (1908) Weller 2.05 7 Lovely Kind & Kindly Loving Op. 55 No. 1(1907) Breton 2.23 8 Scotch Lullabye Op. 57 No. 3 (1908) W Scott 3.37 9 The Watchman (1920) Hildyard 3.15 10 Water-Lilies (1920) O’Reilly 2.06 11 Voices of Vision Op. 24 No. 1 (1903) C Scott 4.42 12 Sundown (1919) Grenside 2.55 Charlotte de Rothschild 13 Autumn’s Lute (1914) R.M Watson 2.05 14 A Valediction Op. 36 No. 1 (1904) Dowson 2.21 Adrian Farmer 15 Lullaby Op. 57 No. 2 (1908) C Rossetti 2.25 Charlotte de Rothschild, soprano Adrian Farmer, piano c & © 2018 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive licence from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK SRCD 365 16 SRCD 365 1 The Songs of Cyril Scott Cyril Scott(1879- 1970) A composer who writes songs arguably allows us into a very personal side of his or her character. An instrumental composition gives us access to a composer’s imagination 16 The Unforeseen Op. -

Rosaleen Norton's Contribution to The

ROSALEEN NORTON’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE WESTERN ESOTERIC TRADITION NEVILLE STUART DRURY M.A. (Hons) Macquarie University; B.A. University of Sydney; Dip. Ed. Sydney Teachers College Submission for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Science University of Newcastle NSW, Australia Date of submission: September 2008 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: Neville Stuart Drury ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, the greater part of which was completed subsequent to admission for the degree. Signed: Date: Neville Stuart Drury 2 CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One: Rosaleen Norton – A Biographical Overview 16 Chapter Two: Sources of the Western Esoteric Tradition 61 Chapter Three: Aleister Crowley and the Magic of the Left-Hand Path 127 Chapter Four: Rosaleen Norton’s Magical Universe 214 Chapter Five: Rosaleen Norton’s Magical Practice 248 Chapter Six: Rosaleen Norton as a Magical Artist 310 Chapter Seven: Theories and Definitions of Magic 375 Chapter Eight: Rosaleen Norton’s Contribution to the Western Esoteric Tradition 402 Appendix A: Transcript of the interview between Rosaleen Norton and L.J. -

Table of Contents Provided by Blackwell's Book Services and R.R

List of Illustrations p. xiii Chronology p. xv Introduction p. xxi The Man Forebears p. 5 [The Aldridge Saga Begins] (1933) [Aldridge Family Strengths] (1933) [Aldridge Family Weaknesses] (1933) [Frank and Clara Aldridge] (1933) Father p. 15 John H. Grainger (1956) [John H. Grainger in Adelaide] (ca. 1933) My Father's Comment on Cyril Scott's Magnificat (1953) Mother's Experience with Scotch & Irish (1953) How Would We Ordinary Men Get On If the Clever Ones Did Not Destroy Themselves? (1953) My Father in My Childhood (1954) Mother p. 27 Dates of Important Events and Movements in the Life of Rose Grainger (1923) [How I Have Loved Her, How I Love Her Now] (1922) Thought Mother Was 'God'. Something of This Still Remains (1923) Arguments with Beloved Mother (1926) Mother's Neuralgia in Australia (1926) Mother on My Love of Being Pitied (1926) Beloved Mother's Swear-Words (1926) Mother a Nietzschean? (1926) Thots of Mother while Scoring To a Nordic Princess (1928) Bird's-Eye View of the Together-Life of Rose Grainger and Percy Grainger (1947) Friends p. 79 [Dr Henry O'Hara] (1933) Dr Hamilton Russell Called Me 'A Tiger for Work' (1953) A Day of Motoring with Dr Russell (1953) Karl Klimsch's Purse of Money, for Mother to Get Well On (1945) The English Are Fickle Friends, Tho Never Vicious in Their Fickleness (1954) My First Meeting with Cyril Scott (1944) Walter Creighton & Cyril Scott (1944) Walter Creighton on Roger Quilter's Hide-Fain-th ((Secretiveness)) (1944) Roger Quilter Failed Me at Harrogate (1944) Balfour Gardiner Disliked What He Considered Political Falsification in Busoni & Harold Bauer (1953) Balfour Gardiner with Me in Norway, 1922 (1953) Mrs L[owrey] and My Early London Days (1945) Frau Kwast-Hiller, Evchen, Mrs Lowrey in Berlin (1953) Miss Devlin's Sweet Australian Ways (1953) Jacques Jacobs on First Ada Crossley Tour (1953) Eliza Wedgewood, Out to Buy Old Furniture from Folksingers (1953) Sargent's and His Set's Set-of-Mind toward My Betrothal to Margot (1944) Wife p. -

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) IGOR STRAVINSKY SOMMCD 266-2 Music for Solo Piano (CD1) Music for Piano and Orchestra (CD2)* Music For

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) IGOR STRAVINSKY SOMMCD 266-2 Music for Solo Piano (CD1) Music for Piano and Orchestra (CD2)* Music for Southampton Piano Solo and Piano and Orchestra TURNER SIMS Peter Donohoe piano Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra * David Atherton conductor * CD1 1 - 3 Three Movements from Petrushka 16:50 4 - 7 Four Etudes, Op. 7 8:19 2000 © 2000. Venue & Personnel as above. & Personnel Venue 2000 © 2000. 8 - bm Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor 29:15 bn - bp Piano Sonata (1924) 10:18 Total duration: 64:43 CD2 1 - 4 Serenade in A 11:43 5 Piano-Rag-Music 3:34 6 Tango 3:13 7 - 9 Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments* 19:18 bl - bp Movements for Piano and Orchestra* 9:30 : Recorded in Tsuen Wan Town Hall, Hong Kong, 4-6 July 1995. Hong Kong, Hall, Town Wan Tsuen in : Recorded bq - bs Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra* 16:35 PETER DONOHOE piano 2000 HK Phil under exclusive licence to GMN Inc to © 2000 GMN licence under exclusive 2000 HK Phil Total duration: 64:04 CD 1 and tracks 1 to 6 of CD 2 recorded 14-16 6 of CD 2 recorded 1 to CD 1 and tracks September 2016 and 24 June 2017 Arden-Taylor. Engineer: Paul Oke. Siva Southampton. Producer: Sims Concert Hall, Turner at Capriccio Earth. Engineer: Mike Floating Johns. Hatch, Stephen Producer: Jan 26-29, 1999. Concerto & Movements: Piano Front cover photo: © 2017 Olivier Fleury / Festival International de Musique de Dinard International de Musique de Dinard © 2017 Olivier Fleury photo: / Festival cover Front Design: Andrew Giles Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra © & 2018 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND DDD Made in the EU DAVID ATHERTON IGOR STRAVINSKY CD 1 IGOR STRAVINSKY CD 2 Three Movements from Petrushka (16:50) Serenade in A (11:43) 1 1. -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

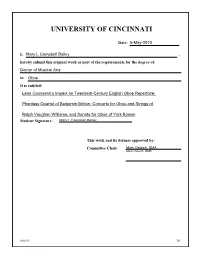

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him. -

Well Beyond the Stage of Being the Objects of Special Pleading by Enthusiasts and Amateurs

well beyond the stage of being the objects of special pleading by enthusiasts and amateurs. The stakes have for some while been far greater, and Lewis Foreman and Paul Hindmarsh, in very different ways, have recognized their responsibilities and risen to them. Foreman, long acknowledged as the foremost authority on Bax, has produced a biography on a scale that throws those of all Bax's English musical peers except Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Sullivan into the shade. It is clearly presented, accurate and full of carefully marshalled information on Bax's wide circle and musical environment (of which the author has unrivalled knowledge)—hence its title. All Bax's works can now be seen in a reliable biographical perspective. Hindmarsh, faced with very full documentation of the circum- stances surrounding Bridge's later works but considerable patches of darkness where the earlier part of his life and career are concerned, has opted for an exemplary thematic catalogue, with a biographical chronology by way of introduction, engraved incipits of all the works, and files of information on each piece which, when they include the author's Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ml/article/66/2/185/1056024 by guest on 30 September 2021 generous and sharply focused commentaries and the liberally quoted extracts from reviews and from Bridge's many letters, make for a handbook to the composer which is every bit as informative as a biography and easier to handle. Both authors have set new standards for the treatment of hitherto overshadowed British twentieth-century composers, and we can rejoice that those following suit will need to meet similar challenges. -

Cyril Scott's Piano Sonata, Op. 66: a Study Of

2M SBU NO. HOQX CYRIL SCOTT'S PIANO SONATA, OP. 66: A STUDY OF HIS INNOVATIVE MUSICAL LANGUAGE, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY MOZART, SCHUMANN, SCRIABIN, DEBUSSY, RAVEL AND OTHERS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Ching-Loh Cheung, B.A., M.M. Denton, Texas May, 1995 2M SBU NO. HOQX CYRIL SCOTT'S PIANO SONATA, OP. 66: A STUDY OF HIS INNOVATIVE MUSICAL LANGUAGE, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY MOZART, SCHUMANN, SCRIABIN, DEBUSSY, RAVEL AND OTHERS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Ching-Loh Cheung, B.A., M.M. Denton, Texas May, 1995 PmP Cheung, Ching-Loh, Cvril Scott's Piano Sonata. OP. 66: A Study of His Innovative Musical Language, with Three Recitals of Selected Works by Mozart. Schumann. Scriabin. Debussy. Ravel and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May, 1995, 55 pp., 37 musical examples, bibliography, 36 titles. The objective of the dissertation is to examine Cyril Scott's musical language as exhibited in his Piano Sonata, Op. 66. Subjects of discussion include Scott's use of form, rhythm, melody, tonality, and harmony. Also included are a biographical sketch of the composer and his philosophical view of modernism. A comparison of the original version and the revised edition of this sonata, as well as references to Cyril Scott's two other piano sonatas are also included during the examination of his harmonic and rhythmic style. -

Possibilities of the Concert Wind Band from the Standpoint of a Modern Composer Percy Grainger

Possibilities of the Concert Wind Band from the Standpoint of a Modern Composer Percy Grainger (Metronome Orchestra Monthly 34/11, November 1918, p.22-3) Modern Wind Band a Product of Recent Musical Thought – Reed and Brass Sections as They Should Exist – Finer Possibilities of Arranging for the Modern Wind Band – Adaptability of Classic and Modern Music to the Needs of a Complete Wind Band – Suggestions for Strengthening the Double-reed Sections – The Percussion Section as it Should Be Perfected. When we consider the latent possibilities of the modern concert wind band it seems almost incomprehensible that the leading composers of our era do not write as extensively for it as they do for the symphony orchestra. No doubt there are many phases of musical emotion that the wind band is not so fitted to portray as is the symphony orchestra, but on the other hand, it is quite evident that in certain realms of musical expressiveness the wind band (not of course the usual band of small proportions as we most often encounter it, but an ideal band of some fifty pieces or more) has no rival. It is not so much the wind band as it already is, in the various countries, that should engage the creative attentions of contemporary composers of genius, as the band that should be and will be; for it is in a pliable state as regards its make-up as compared with the more settled form of the sound-ingredients of the symphony orchestra. Those who are interested in exploring the full latent possibilities of the modern concert wind band should consult Arthur A. -

Bibliography of Materials and Works Cited

Nalini Ghuman, Resonances of the Raj (Oxford University Press, 2014) Bibliography of materials and works cited 1. Manuscript Sources and Archival Collections Maud MacCarthy and John Foulds Composer John Foulds Files I (1924-1938) and II (1940-1958), BBC Written Archives in Caversham, part of the UK National Archives (BBC WAC) Foulds, ‘A Few Indian Records’, John Foulds Sketches and Papers, Private Family Collection, held in trust by Malcolm MacDonald (UK) (JF Papers) Foulds, letter to George Bernard Shaw, April 25 1925, British Library (BL) Add MS 50519 f. 224 Foulds, MS list of works, BL Add Mss 56483 Foulds, MS Collection, BL Add Mss 56482 Foulds, Orpheus Abroad. Series of twelve radio programmes broadcast from All India Radio in Delhi on the following dates in 1937: 6, 13, 23, 31 March; 7, 18, 22, 28 April; 2, 14, 22, 30 May; Scripts held in Maud MacCarthy Papers, Private Family Collection (MM Papers) Foulds, two letters to Maud MacCarthy, BL Add MS 56478 John Foulds Autograph Manuscript Scores. Collection of Graham Hatton (Hatton & Rose, UK) John Foulds Sketches and Papers, Private Family Collection, held in trust by Malcolm MacDonald (UK) (JF Papers) MacCarthy-Foulds Papers, Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York (UK) (Borthwick Archive) Maud MacCarthy Papers, Private Family Collection (MM Papers) 1 Walter Kaufmann Archive, The William and Gayle Cook Music Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Walter Kaufmann Composer File: BBC WAC Sir Edward Elgar Arnold, Edwin. ‘Imperial Ode’, written for India by Imre Kiralfy. 1895. BL: 1779. K. 6, folio 5 ‘Crystal Palace Programme and Guide to Entertainments, 1901’. -

Draft 10 May 11

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Piano Performance in Musical Symbolism: Interpretive Freedom through Understanding Symbolist Aesthetics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5cg463h0 Author Wong, Wan Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Piano Performance in Musical Symbolism: Interpretive Freedom through Understanding Symbolist Aesthetics A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Wan Wong 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Piano Performance in Musical Symbolism: Interpretive Freedom through Understanding Symbolist Aesthetics by Wan Wong Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Inna Faliks, Chair Studies in musical symbolism are often interdisciplinary, with collaboration with areas to do with the literary and visual arts. My dissertation re-orients the focus to the non-representative function of symbols and engages with symbolist thought and the hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer in an effort to justify musical analysis of Symbolist music through identifying effects and atmospheres. In part one, I present a general overview of Symbolist aesthetics, drawing largely from Claude Debussy’s writing Monsieur Croche: the Dilettante Hater. In part two, I liken the total experience of piano performance to Gadamer’s concept of play and festival in or- der to explicate the mechanisms of symbols in musical symbolism. Part three features Symbolist piano pieces based on its effects—fluidity and stasis—and provides a closer look into interpreta- tion and performance. ii This dissertation of Wan Wong is approved. -

“Men and Music”

“Men And Music” by Dr. Erik Chisholm Lectures given at University of Cape Town Summer School, February 1964 Published by The Erik Chisholm Trust June 2014 www.erikchisholm.com Copyright Notice The material contained herein is attributed to The Erik Chisholm Trust and may not be cop- ied or reproduced without the prior permission of the Trust. All enquiries regarding copyright should be sent to the Trust at [email protected] © 2014 The Erik Chisholm Trust 2 Dr. Erik Chisholm (1904—1965) 3 Credits Fonts: Text - Calibri Headings - Segro Script Compiled in Microsoft Publisher 2013 4 Introduction by the Editor In 1964 Chisholm gave a series of lectures on Men and Music, illustrated with music and slides, at the UCT Summer School. In his own words Men and Music wasn’t “going to be a serious business. It will con- sist mainly of light hearted reminiscences about some important figures in 20th Century music, from which it will be possible to gain insight into their characters and personalities.” Many distinguished composers came to Glasgow in the 1930’s to give concerts of their works for the Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music (a bit of a mouthful, known colloquially as The Active Society). The 18 composers he talks about are William Walton, Cyril Scott, Percy Grainger, Eugene Goosens, Bela Bartok, Donald Tovey, Florent Schmitt, John Ireland, Yvonne Arnaud, Frederick Lamond, Adolph Busch, Alfredo Casella, Arnold Bax, Paul Hindemith, Dmitri Shostakovich (Chisholm cheated here- Shostakovich didn’t actually appear but they were friends and the Active Society “played quite a lot of his music”), Kai- koshru Sorabji, Bernard van Dieren and Medtner.