EXTENDED-RANGE OBOE: the IMPACT of TECHNICAL and MUSICAL ADVANCEMENTS in 19Th-CENTURY and CONTEMPORARY OBOE REPERTOIRE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

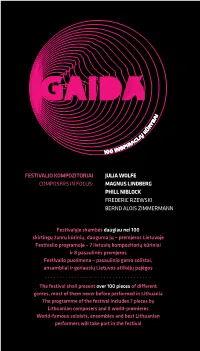

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger's

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) Kevin Davis “In particular, the String Quartet is an extreme example of a music of effects rather than of 'ideas' in any conventional sense. The result, beginning with frantic high harmonics and ending, some twenty-six and a half minutes later, with the barely perceptible breathing of the players, is music whose expression is always utterly clear and direct, but which seems mechanical in its apparent rejection of the kind of relationships between significant detail and overall shape and perspective through which most music communicates.” – Arnold Whitall, Gramophone, August 1981 Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) is a landmark work. It challenges the listener and performer alike, posing many questions and giving only tentative answers. While still obeying the basic rules and conventions of string quartet discourse and notation, it methodically strips away the artifice of performance, working from the inside out. It comes into being in a furious flurry of activity. Organic processes play themselves out to exhaustion, reaching termination less through the end of a compositional process than through something like a loss of entropy; musical form attempts to assert itself and is subsumed in the welter of activity; technique and the instruments themselves become deformed, barely able to retain their identity, threatening to become only the wood and metal from which they are made. Eventually exhaustion is reached, both on the part of composer and, one must assume, on the part of the players. Then something mysterious happens: first, after this inexorable, almost ritualistic revealing of the instrument, then, finally, the body of the performer, which has been residing underneath the sounds all along, emerges. -

Cordelia''s Portrait in the Context of King Lear''s

Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez Cordelias Portrait in the Context of King Lears... 181 CORDELIAS PORTRAIT IN THE CONTEXT OF KING LEARS INDIVIDUATION* Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez** Abstract: This analysis attempts to show the relations between the individual psyche and the contents of the collective unconscious. Following Von Franzs analytical technique, the tragic action in King Lear will be read as an individuation process that will rescue archetypal contents and solve existential paradoxes that cause an imbalance between the ego and the self, leading to self-destruction. Once communication is eased and balance is restored, the transformation-seeking process that engaged the design of the play itself becomes resolved, and events can be led to a conventional tragic resolution. Jungian analysis will therefore provide a critical framework to unveil the subconscious contents that tear the character of the king between annihilation and survival, the anima complex that affects the king, responding thus for the action of the play and its centuries-old success. Keywords: collective unconscious, myth, individuation, archetype, tragedy, anima. Resumen: Este análisis pretende sacar a la luz las relaciones entre la psyche individual y los contenidos del inconsciente colectivo. Siguiendo la técnica analítica de Von Franz, la acción trágica de King Lear será entendida a través del proceso de individuación que revierte sobre los contenidos arquetípicos y resuelve las paradojas existenciales que cau- san el desequilibrio entre ego y self. Una vez que la comunicación es facilitada y el equilibrio psíquico recuperado, el proceso transformativo que afecta la génesis de la trama se resuelve y el argumento alcanza una resolución convencional. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson

Some Recent Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson The original European Universal Eloquence label replaced budget releases on DG (Privilege or Resonance), Decca (Weekend Classics) and Philips (Classical Favourites). Like them it originally sold for around £5 and offered some splendid bargains such as Telemann’s ‘Water Music’ and excerpts from Tafelmusik (Musica Antiqua Köln/Reinhard Goebel 4696642) and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Janet Baker, James King, Concertgebouw/Bernard Haitink 4681822). Later most of the original batch were deleted – luckily the Mahler remains available – and production switched to Universal Australia but the price remained around the same. More recently changes in the value of the £ mean that single CDs now sell for around £7.75 but the high quality of much of the repertoire means that they remain well worth keeping an eye on. Many, but not all, of the albums are available to stream or download and I have reviewed some in that form and others on CD. Be aware, however, that the downloads often cost more than the CDs and invariably come without notes – which is a shame because the Eloquence booklets are better than those of many budget labels. THE TUDORS Lo, Country Sports Anonymous Almain Thomas TOMKINS Adieu, Ye City-Prisoning Towers Thomas WEELKES Lo, Country Sports that Seldom Fades Nicholas BRETON Shepherd and Shepherdess Michael EAST Sweet Muses, Nymphs and Shepherds Sporting Bar YOUNG The Shepherd, Arsilius’s, Reply John FARMER O Stay, Sweet Love Giles FARNABY Pearce did love fair Petronel Michael -

Grieg Piano Concerto in a Minor Shee

Grieg piano concerto in a minor shee Continue Piano Concerto in the minor is directing here. See the piano concerto (Schumann) for the Robert Schumann concert. Music scores are temporarily disabled. Famously a flourishing introduction to concerts. Piano Concerto in Underage Op. 16, composed by Edvard Grieg in 1868, was the only concert Grieg finished. It is one of his most popular works[1] and is one of the most popular piano concertoes. Structure Musical scores are temporarily disabled. The main topic of allegro molto moderato. The concert is in three movements:[2] Allegro molto moderato (minor) The first movement is in sonata form and is known as timpani roll in its first bar, which leads to a dramatic piano bloom, which leads to the main theme. Then the key becomes a C large, secondary theme. Later the secondary theme appears again recapitulation, but this time the key major. The movement ends with virtuosic cadenza and bloom similar to that at the beginning of the movement. Adagio (D♭) The second movement is the lyrical movement D♭ large, leading directly to the third movement. The movement is in three-set form (A-B-A). Part B is D♭ and E large, then returns to D♭ a large reprise piano. Allegro moderato molto e marcato - Quasi presto - Andante maestoso (minor → F large → minor → large) the third movement opens a minor 24 times energetic theme (Theme 1), followed by a lyrical theme F large (Theme 2). The move will return to the theme on 1 January 2017. After this total cepteption is 34 main Quasi presto section, consisting of a variation of theme 1. -

(Pdf) Download

ATHANASIOS ZERVAS | BIOGRAPHY BRIEF BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He holds a DM in composition and a MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with Frank Garcia, M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke, and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice “Bunky” Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner. Dr. Athanasios Zervas is an Associate Professor of music theory-music creation at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki Greece, Professor of Saxophone at the Conservatory of Athens, editor for the online theory/composition journal mus-e-journal, and founder of the Athens Saxophone Quartet. COMPLETE BIOGRAPHY ATHANASIOS ZERVAS is a prolific composer, theorist, performer, conductor, teacher, and scholar. He has spent most of his career in Chicago and Greece, though his music has been performed around the globe and on dozens of recordings. He is a specialist on pitch-class set theory, contemporary music, composition, orchestration, improvisation, music of the Balkans and Middle East, and traditional Greek music. EDUCATION He holds a DM in composition and an MM in saxophone performance from Northwestern University, and a BA in music from Chicago State University. He studied composition with M. William Karlins, William Russo, Stephen L. Syverud, Alan Stout, and Jay Alan Yim; saxophone with Frederick Hemke and Wayne Richards; jazz saxophone and improvisation with Vernice ‘Bunky’ Green, Joe Daley, and Paul Berliner; and jazz orchestration/composition with William Russo. RESEARCH + WRITING Dr. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 629. - 2 - January 2018 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Agababov: Passacaglia, Ballet Suite - cond.E.Khachaturian 10" MELODIYA D 12839 A 30 2 Akbarov: Khamza film music - Kabulova, cond.Shamsutdinov 10" MELODIYA D 8693 A 15 3 Amemiya, Yasukazu: Summer Prayer, Monochrome Sea Both with tape)/Morton RCA RVC 2154 A 15 Feldman: The King of Denmark - Y.Amemiya percussions (Japanese issue) (1977) S 4 Andriessen, Louis: Nocturnen/Flothuis, Marius: Canti e Giuochi/Orthel, Leon: DONEMUS DAVS 6504 A 8 Scherzo II - E.Lugt sop, cond.Haitink, Jordans (complete score) 1965 10" 5 Antheil: Sym 5/ W.Josten: Endymion ballet - Vienna PO, cond.Haefner SPA 16 A 10 6 Arel: Electronic Music #1, Fragment, Prel/Davidovsky: Study #2/Ussachevsky: SON-NOVA SN 1988 A 25 Metamorphosis (all electronic music) S 7 Arnestad, Finn: Violin Concerto (O.Bohn vln, cond.Ingebretsen), INRI (cond.Kamu) NORWEGIAN NC 6007 A 10 (p.1985) S 8 Arutyunyan: Pno Concertino (comp.pno)/ Morzoyan: Dance Suite - Armenian SSO, MELODIYA D 3084 A 18 cond.Maluntsyan 10" 9 Asakawa, Haruo: Piano Sonata/O.Katsuki: 3 Poems/K.Hattori: Divertimento for 12 JFC JFC-R 8002 A 8 Voices & 2 Celli/A.Komori: Psalterium for Percs S 10 Ashley, Robert: In Memoriam Crazy Horse (Sym)/G.Cacioppo: Time on Time in ADVANCE FGR 5 A 85 Miracles, Cassiopeia (2 pfs)/G.Mumma: Music from the Venezia/D.Scavarda: Landscape Jurney (1966) 11 Auric, Georges: Fontaine de Jouvence Suite, Malborough ballet (cond.Leibowitz)/ RENAISSANC X 41 A 15 P.Gradwohl: Divertissement Champetre (cond.comp) 12 Auric: Partita for 2