Current Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger's

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) Kevin Davis “In particular, the String Quartet is an extreme example of a music of effects rather than of 'ideas' in any conventional sense. The result, beginning with frantic high harmonics and ending, some twenty-six and a half minutes later, with the barely perceptible breathing of the players, is music whose expression is always utterly clear and direct, but which seems mechanical in its apparent rejection of the kind of relationships between significant detail and overall shape and perspective through which most music communicates.” – Arnold Whitall, Gramophone, August 1981 Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) is a landmark work. It challenges the listener and performer alike, posing many questions and giving only tentative answers. While still obeying the basic rules and conventions of string quartet discourse and notation, it methodically strips away the artifice of performance, working from the inside out. It comes into being in a furious flurry of activity. Organic processes play themselves out to exhaustion, reaching termination less through the end of a compositional process than through something like a loss of entropy; musical form attempts to assert itself and is subsumed in the welter of activity; technique and the instruments themselves become deformed, barely able to retain their identity, threatening to become only the wood and metal from which they are made. Eventually exhaustion is reached, both on the part of composer and, one must assume, on the part of the players. Then something mysterious happens: first, after this inexorable, almost ritualistic revealing of the instrument, then, finally, the body of the performer, which has been residing underneath the sounds all along, emerges. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03 1 Première Rapsodie pour orchestre 7 Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune [11:35] Diese wesensmäßige Fertigkeit hatte schon in den Chemie“, an der er sich selbst immer neu ergötzen avec clarinette principale [08:15] flûte solo: Tatjana Ruhland frühen Neunzigern die Bedenken des Dichters konnte, und die aus sich selbst erwachsenden For- Stéphane Mallarmé zerstreut, der zunächst von men in Regelwerke zu zwängen, sich im Geflecht Images pour orchestre 8 Rapsodie pour Debussys Ansinnen, die Ekloge vom Après-midi des Gefundenen, bereits „Gehabten“ zu verhed- Deutsch 2 Rondes de Printemps [08:29] orchestre et saxophone [09:45] d’un faune mit Musik zu umgeben, nicht begeis- dern. Vielleicht wurde daher auch nur das Prélude 3 Gigues [08:38] tert war. Er fürchtete eine bloße „Verdopplung“ zum „Faun“ vollendet, während das Interlude und Iberia [19:48] TOTAL TIME [67:04] seiner musikalisch-erotischen Alexandriner, sah die abschließende Paraphrase nie über die Idee 4 I. Par les rues et par les chemins [07:09] sich aber, kaum dass er das Resultat zu hören be- hinausgelangten. Es war schon alles gesagt. 5 II. Les parfums de la nuit [08:10] 1 Dirk Altmann Klarinette | clarinet kam, ebenso bezwungen wie die Besucher der 6 III. Le matin d'un jour de fête [04:28] 8 Daniel Gauthier Saxophon | saxophone Société Nationale, die am 22. Dezember 1894 die Wer weiß, ob nicht aus just diesem Grunde auch Uraufführung des Prélude „zum Nachmittag eines die Rapsodie arabe im Sande verlief, die sich der Fauns“ miterleben durften. -

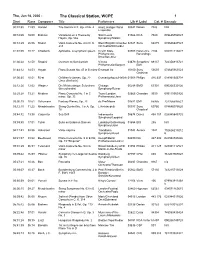

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Jun 18, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:59 Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A Ensemble 00:14:2918:00 Brahms Variations on a Theme by Saint Louis 01966 RCA 7920 078635792027 Haydn, Op. 56a Symphony/Slatkin 00:33:29 26:06 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Stern/English Chamber 02925 Sony 66475 074646647523 218 Orchestra/Schneider 01:01:0528:17 Chadwick Aphrodite, a symphonic poem Czech State 03308 Reference 2104 030911210427 Philharmonic, Recordings Brno/Serebrier 01:30:2212:50 Rossini Overture to Semiramide Vienna 03679 Seraphim/ 69137 724356913721 Philharmonic/Sargent EMI 01:44:1214:53 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 47 in B minor Emanuel Ax 10100 Sony 53635 074645363523 Classical 02:00:3510:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 02:12:2612:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 02:25:2833:21 Medtner Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Tozer/London 02666 Chandos 9039 095115903926 minor, Op. 33 Philharmonic/Jarvi 03:00:1910:51 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 du Pre/Moore 09531 EMI 65955 724356595521 03:12:1031:22 Mendelssohn String Quintet No. 1 in A, Op. L'Archibudelli 05537 Sony 60766 074646076620 18 Classical 03:44:32 13:38 Carpenter Sea Drift Indianapolis 08678 Decca 458 157 028945845725 Symphony/Leppard 03:59:4017:01 Tubin Suite on Estonian Dances Lubotsky/Gothenburg 01654 BIS 286 N/A Symphony/Jarvi 04:17:41 02:56 Halvorsen Valse caprice Trondheim 01943 Aurora 1921 702626219212 Symphony/Ruud 6 04:21:3738:22 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him. -

The Protean Oboist: an Educational Approach to Learning Oboe Repertoire from 1960-2015

THE PROTEAN OBOIST: AN EDUCATIONAL APPROACH TO LEARNING OBOE REPERTOIRE FROM 1960-2015 by YINCHI CHANG A LECTURE-DOCUMENT PROPOSAL Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2016 Lecture Document Approval Page Yinchi Chang “The Protean Oboist: An Educational Approach to Learning Oboe Repertoire from 1960- 2015,” is a lecture-document proposal prepared by Yinchi Chang in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This lecture-document has been approved and accepted by: Melissa Peña, Chair of the Examining Committee June 2016 Committee in Charge: Melissa Peña, Chair Dr. Steve Vacchi Dr. Rodney Dorsey Accepted by: Dr. Leslie Straka, Associate Dean and Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School ii © 2016 Yinchi Chang iii CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yinchi Chang PLACE OF BIRTH: Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C DATE OF BIRTH: April 17, 1983 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon University of Redlands University of California, Los Angeles Pasadena City College AREAS OF INTEREST: Oboe Performance Performing Arts Administration PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Marketing Assistant, UO World Music Series, Eugene, OR, 2013-2016 Operations Intern, Chamber Music@Beall, Eugene, OR, 2013-2014 Conductor’s Assistant, Astoria Music Festival, Astoria, OR 2013 Second Oboe, Redlands Symphony, Redlands, CA 2010-2012 GRANTS, AWARDS AND HONORS: Scholarship, University of Oregon, 2011-2013 Graduate Assistantship, University of Redlands, 2010-2012 Atwater Kent Full Scholarship, University of California, Los Angeles, 2005-2008 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Heinz Holliger

Künstlersekretariat Barbara Golan Tel. +41 44 322 07 04 Barbara Golan Fax +41 44 322 07 24 Stettbachstrasse 131H Mail: [email protected] CH-8051 Zürich Web: www.golanartists.ch _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Heinz Holliger Heinz Holliger is among the most versatile and most extraordinary musical personalities of our time. After taking first prizes in the international competitions in Geneva and Munich, Mr. Holliger began an incomparable international career that has taken him to the great musical centres on five continents. Exploring both composition and performance, he has extended the technical possibilities of his instrument while deeply committing himself to contemporary music. Some of the most important composers of the present day have dedicated works to Mr. Holliger, who also advocates certain lesser-known works and composers. Heinz Holliger’s many honours and prizes include the Composer’s Prize from the Swiss Musician’s Association, the City of Copenhagen’s Léonie Sonning Prize for Music, Art Prize of the City of Basel, the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, the City of Frankfurt’s Music Prize, the Abbiati Prize at the Venice Biennale, an honorary doctorate from the University of Zürich, a Zürich Festival Prize and the Rheingau Music Prize, among others, as well as awards for recordings - the Diapason d’Or, the Midem Classical Award, the Edison Award, the Grand Prix du Disque, and others. As a conductor, Heinz Holliger -

Uto Ughi Violinist LEON POMMERS, Pianist

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Uto Ughi Violinist LEON POMMERS, Pianist FRIDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 20, 1981, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Sonata in D Major ............ HANDEL Adagio Allegro Larghetto Allegro Partita No. 2 in D minor ........... BACH Allemande Courante Sarabande Gigue Chaconne INTERMISSION Sonata No. 9 in A major, Op. 47 ("Kreutzer") ..... BEETHOVEN Adagio sostenuto Presto Andante con variazioni Presto RCA Records. Twentieth Concert of the 103rd Season Sixth Annual Debut & Encore Series About the Artist Uto Ughi, Italian virtuoso born near Milan in 1944, made his debut as a soloist at the age of seven, when he presented a program which included the Chaconne from Bach's Partita in D minor and some of Paganini's Caprices. He studied under the direction of the famed composer and violinist, Georges Enesco, and in 1959 made his first concert appearances in all the major cities of Europe: Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin, Oslo, Amsterdam, Madrid, and Barcelona. Mr. Ughi has since performed throughout Europe, in North and South America, South Africa, the Soviet Union, and Japan, under such famous conductors as Sir John Barbirolli, Andre Cluytens, Kiril Kondrashin, Efrem Kurtz, Carlo Maria Giulini, Bernard Haitink, Gennady Rozdestvensky, Sir Malcolm Sargent, and Wolfgang Sawallisch. He plays the "Van Houten-Kreutzer" Stradivarius, made in 1701, which, according to a reliable tradition, was once the property of Rudolf Kreutzer, the friend to whom Beethoven dedicated the Sonata in A major, Op. 47. Mr. Ughi performs this work on tonight's program, in his Ann Arbor debut. Coming Events CESARE SIEPI, Basso ......... -

Composer Brochure

CARTER lliott E composer_2006_01_04_cvr_v01.indd 2 4/30/2008 11:32:05 AM Elliott Carter Introduction English 1 Deutsch 4 Français 7 Abbreviations 10 Works Operas 12 Full Orchestra 13 Chamber Orchestra 18 Solo Instrument(s) and Orchestra 19 TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS Ensemble and Chamber without Voice(s) 23 Ensemble and Chamber with Voice(s) 30 Piano(s) 32 Instrumental 34 Choral 39 Recordings 40 Chronological List of Works 46 Boosey & Hawkes Addresses 51 Cover photo: Meredith Heuer © 2000 Carter_2008_TOC.indd 3 4/30/2008 11:34:15 AM An introduction to the music of Carter by Jonathan Bernard Any composer whose career extends through eight decades—and still counting—has already demonstrated a remarkable staying power. But there are reasons far more compelling than mere longevity to regard Elliott Carter as the most eminent of living American composers, and as one of the foremost composers in the world at large. His name has come to be synonymous with music that is at once structurally formidable, expressively extraordinary, and virtuosically dazzling: music that asks much of listener and performer INTRODUCTION alike but gives far more in return. Carter was born in New York and, except during the later years of his education, has always lived there. After college and some postgraduate study at Harvard, like many an aspiring American composer of his generation who did not find the training he sought at home, Carter went off to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, an experience which, while enabling a necessary development of technique, also lent his work a conservative, neoclassical style for a time. -

Isang Yun Maderna, Heinz Holliger, Hans Zender, Zubin Mehta, Jesús López-Cobos, Myung-Whun Chung, and Many More

_Bara_ in Berlin in 1962. The conductors of Yun’s works have included Bruno Isang Yun Maderna, Heinz Holliger, Hans Zender, Zubin Mehta, Jesús López-Cobos, Myung-Whun Chung, and many more. It is hardly possible to list all the soloists who have mastered his very demanding scores. The connection to the tradition of Chinese-Korean court music is very clear in _Loyang_ for chamber ensemble (1962). Yun’s individual style, which is indeed obliged to Eastern-Asian idioms, emerged in _Gasa_ for violin and piano (1963) and in _Garak_ for flute and piano (1963). In _Gasa_ and _Garak_, he overlaid twelve-tone sound fields with a second, melodically dominated layer of (long sustained) main or central tones. Yun recognized Isang Yun photo © Booseyprints this long sustained tone (or sound), which "is already life itself" and – flexible within itself – contains beats, colorings, dynamic nuances, and also The Dragon from Korea ornaments (accentuated attacks, sub-beats, likewise emphasized decays), as _by Walter-Wolfgang Sparrer an essential characteristic of the East-Asian tradition. _ Isang Yun was the first composer from Eastern Asia to succeed in That he meticulously indicated in his scores the course of every individual establishing an international career based in Germany. With the Seoul tone center – Yun spoke of "main tones" – like the articulation of a word, was Cultural Prize in 1955, he received the most prestigious award conferred by new in the history of music and created certain difficulties in the execution of his South Korean homeland. He used the prize money to travel the following his imaginatively delicate, and yet in no way merely playfully demanding year, in June 1956, to Paris, where he wanted to get to know the at that time ornamental music. -

Page 1/4 2017 Summer Festival Theme of “Identity”

2017 Summer Festival Theme of “Identity” Who am I? The issue of identity illuminates the human condition in the present and through history in its relation to origin, homeland, faith, culture, and religion. How did we become the people we are? And how are we changed by our current environment? Paradigmatic answers to these questions can be found in the fates of such composers as Béla Bartók, Gustav Mahler, Sergei Prokofiev, and Dmitri Shostakovich. But they also come up in general for every musician involved in the international concert scene. Like nomads they travel around the world, performing today in New York and tomorrow in Tokyo. And the issue of identity is highly controversial, as we see in the case of refugees who are coming to Europe from war zones and who have to choose between the desire to integrate and the preservation of what is uniquely their own. Selected Themes/Projects/Related Events Monteverdi Cycle English Baroque Soloists | Monteverdi Choir | Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor | Soloists The operas of Monteverdi reach back to the KKL Luzern very origins of Western culture and its myths, and to the birth of the genre of opera. They 22 August | 19.30 | L’Orfeo depict humans in all their emotions, 25 August | 18.30 | Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria distortions, and psychological depths. 26 August | 18.30 | L’incoronazione di Poppea Concerts exploring the theme of “Identity” Special Event Day on Sunday, 27 August from different perspectives KKL Luzern 1 “The Path of Slavery” – Music from six Hespèrion XXI | La Capella Reial de Catalunya | centuries Jordi Savall conductor | Soloists 2 Kodály The Imperial Adventures of Háry Symphony Concert with the Basel Symphony page 1/4 János Orchestra, also for children (ages 7 and up) 3 Recital for violin, cello, and piano: works by Patricia Kopatchinskaja violin | Jay Campbell Enescu, Kodály, Ravel cello | Polina Leschenko piano 4 Mahler: Symphony No. -

Robert Schumann Vol. Ii

ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works VOL. II HEINZ HOLLIGER WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. II recording date: January 23-27, 2012 (Symphony No. 2) March 19-23, 2012 (Symphony No. 3) Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61 36:10 I. Sostenuto assai – Allegro ma non troppo 12:01 P Eine Produktion des Westdeutschen Rundfunks Köln, 2012 II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace 7:03 lizenziert durch die WDR mediagroup GmbH III. Adagio espressivo 8:26 recording location: Köln, Philharmonie IV. Allegro molto vivace 8:40 executive producer (WDR): Siegwald Bütow recording producer & editing: Günther Wollersheim recording engineer: Brigitte Angerhausen Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 97 ‘Rhenish’ 30:35 Recording assistant: Astrid Großmann I. Lebhaft 8:58 photos: Heinz Holliger (page 8): Julieta Schildknecht II. Scherzo. Sehr mäßig 5:40 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 5): WDR Thomas Kost III. Nicht schnell 5:08 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 9): Mischa Salevic IV. Feierlich 5:04 front illustration: ‘Sonnenuntergang (Brüder)’ Caspar David Friedrich V. Lebhaft 5:45 art direction and design: AB•Design executive producer (audite): Dipl.-Tonmeister Ludger Böckenhoff e-mail: [email protected] • http: //www.audite.de HEINZ HOLLIGER © 2014 Ludger Böckenhoff WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Robert Schumann‘s instrumental sound – the sound towards The C-major Symphony not only sketched, but also developed. Symphonies which Brahms and Franck also strove” He also spent more time revising works, A peculiar contradiction has marked the (Jon W. Finson). He attained it, above all, If one were to count Schumann’s Sym- both during their preparatory stages and reception of Schumann’s symphonies.