Robert Schumann Vol. Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me Israel Aestra JULU 3-QUGUSU 8 1979 Me Israel Assam Founoed Bu A.Z

me Israel Aestra JULU 3-QUGUSU 8 1979 me Israel Assam FOunoeD bu a.z. ppopes JULU 3-aUGUSB 8 1979 Member of the European Association of Music Festivals Executive Committee: Asher Ben-Natan, Chairman Honorary Presidium: ZEVULUN HAMMER - Minister of Education and Culture Menahem Avidom GIDEON PATT - Minister of Industry, Trade and Tourism Gary Bertini TEDDY KOLLEK - Mayor of Jerusalem Jacob Bistritzky Gideon Paz SHLOMO LAHAT - Mayor of Tel Aviv-Yafo Leah Porath Ya'acov Mishori Jacob Steinberger J. Bistritzky Director, the Israel Festival. Director, The Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition. Thirty years of professional activity in Artistic Advisor — Prof. Gary Bertini the field of culture and arts, as Director of the Department of International The Public Committee and Council: Cultural Relations in the Ministry of Gershon Achituv Culture and Arts, Warsaw; Director of the Menahem Avidom Polish Cultural Institute, Budapest: Yitzhak Avni Director of the Frédéric Chopin Institute, Warsaw. Mr. Bistritzky's work has Mordechai Bar On encompassed all aspects of the Asher Ben-Natan Finance Committee: development of culture, the arts and mass Gary Bertini Menahem Avidom, Chairman media: promotion, organization and Jacob Bistritzky Yigal Shaham management of international festivals and Abe Cohen Micha Tal competitions. Organizer of Chopin Sacha Daphna competitions in Warsaw and International Meir de-Shalit Chopin year 1960 under auspices of Walter Eytan Festival Staff: U.N.E.S.C.O. Shmuel Federmann Assistant Director: Ilana Parnes Yehuda Fickler Director of Finance: Isaac Levinbuk Daniel Gelmond Secretariat: Rivka Bar-Nahor, Paula Gluck Dr. Reuven Hecht Public Relations: Irit Mitelpunkt Dr. Paul J. -

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger's

A Systematic Dismantling: Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) Kevin Davis “In particular, the String Quartet is an extreme example of a music of effects rather than of 'ideas' in any conventional sense. The result, beginning with frantic high harmonics and ending, some twenty-six and a half minutes later, with the barely perceptible breathing of the players, is music whose expression is always utterly clear and direct, but which seems mechanical in its apparent rejection of the kind of relationships between significant detail and overall shape and perspective through which most music communicates.” – Arnold Whitall, Gramophone, August 1981 Heinz Holliger’s Streichquartett (1973) is a landmark work. It challenges the listener and performer alike, posing many questions and giving only tentative answers. While still obeying the basic rules and conventions of string quartet discourse and notation, it methodically strips away the artifice of performance, working from the inside out. It comes into being in a furious flurry of activity. Organic processes play themselves out to exhaustion, reaching termination less through the end of a compositional process than through something like a loss of entropy; musical form attempts to assert itself and is subsumed in the welter of activity; technique and the instruments themselves become deformed, barely able to retain their identity, threatening to become only the wood and metal from which they are made. Eventually exhaustion is reached, both on the part of composer and, one must assume, on the part of the players. Then something mysterious happens: first, after this inexorable, almost ritualistic revealing of the instrument, then, finally, the body of the performer, which has been residing underneath the sounds all along, emerges. -

What's on in Tel Aviv / January

WHAT'S ON IN TEL AVIV / JANUARY MUSIC EVENTS ECHOES PINK FLOYD MAD PROFESSOR SATYRICON 04 LIVE TRIBUTE SHOW 12 AND GAUDI 24 Barby Club Reading 3 Barby Club LED ZEPPELIN 2 – MAURICE EL MEDIONI MANOLIA 07 THE LIVE EXPERIENCE 12 AND NETA ELKAYAM 24 GREEK HITS 08 Bronfman Auditorium Einav Culture Center Suzanne Dellal Center SWING AND RAY GELATO CHRONOS PROJECT THE KOOKS 11 JAZZ CONCERT 15 BY DIMITRA GALANI 27 Barby Club 12 Tel Aviv Museum of Art Tel Aviv Museum of Art 28 MAIN CLASSICAL DANCE 1-4 THE RACE TO THE VIENNA BALL 5-6 THE YOUNG ENSEMBLE, BATSHEVA Strauss, Brahms, Smetana and Dvorak DANCE COMPANY - KAMUYOT Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center Suzanne Dellal Center 5-6 INBAL PINTO AND AVSHALOM POLLAK - OYSTER Suzanne Dellal Center THINGS TO DO FOR FREE ANTIQUE & SECOND HAND ITEMS FAIR Every Tuesday at 10 AM-6 PM and every Friday at 7 AM-4 PM 9 CHRIS ROCK STAND UP SHOW Givon Square Menora Mivtachim Arena TEL AVIV PORT TOUR 19-20 VERTIGO DANCE COMPANY AND Every Thursday at 11 AM REVOLUTION ORCHESTRA - WHITE NOISE Meeting point: Aroma Cafe, 1 Yordei HaSira Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center St. Hangar 9, Tel Aviv Port 4-17 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM DESIGNERS & FOOD MARKET Opera Every Thursday and Friday, Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center FOR KIDS Dizengoff Center 5 CHRISTMAS VIENNESE BALL 6 BUTTERFLIES IN THE STOMACH TETRIS GAME ON THE St. Nicolas Monastery, Old Jaffa Mediatek, Holon• CITY HALL BUILDING 6 UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS 13 ALICE IN WONDERLAND Every Thursday evening - Rabin Square* DANGEROUS LIAISONS IN MOZART’S OPERAS Circus Y, Circus Tent, Ramat Gan Stadium• SARONA TOUR Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center 13,27 GULLIVER (PLAY) Every Friday at 11 AM 16 BACH – BERNSTEIN Gesher Theatre Meeting point: Sarona Visitor’s Center, 11 Avraham Albert Mendler St. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03 1 Première Rapsodie pour orchestre 7 Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune [11:35] Diese wesensmäßige Fertigkeit hatte schon in den Chemie“, an der er sich selbst immer neu ergötzen avec clarinette principale [08:15] flûte solo: Tatjana Ruhland frühen Neunzigern die Bedenken des Dichters konnte, und die aus sich selbst erwachsenden For- Stéphane Mallarmé zerstreut, der zunächst von men in Regelwerke zu zwängen, sich im Geflecht Images pour orchestre 8 Rapsodie pour Debussys Ansinnen, die Ekloge vom Après-midi des Gefundenen, bereits „Gehabten“ zu verhed- Deutsch 2 Rondes de Printemps [08:29] orchestre et saxophone [09:45] d’un faune mit Musik zu umgeben, nicht begeis- dern. Vielleicht wurde daher auch nur das Prélude 3 Gigues [08:38] tert war. Er fürchtete eine bloße „Verdopplung“ zum „Faun“ vollendet, während das Interlude und Iberia [19:48] TOTAL TIME [67:04] seiner musikalisch-erotischen Alexandriner, sah die abschließende Paraphrase nie über die Idee 4 I. Par les rues et par les chemins [07:09] sich aber, kaum dass er das Resultat zu hören be- hinausgelangten. Es war schon alles gesagt. 5 II. Les parfums de la nuit [08:10] 1 Dirk Altmann Klarinette | clarinet kam, ebenso bezwungen wie die Besucher der 6 III. Le matin d'un jour de fête [04:28] 8 Daniel Gauthier Saxophon | saxophone Société Nationale, die am 22. Dezember 1894 die Wer weiß, ob nicht aus just diesem Grunde auch Uraufführung des Prélude „zum Nachmittag eines die Rapsodie arabe im Sande verlief, die sich der Fauns“ miterleben durften. -

Levit Spielt Brahms Fr 7

LEVIT SPIELT BRAHMS FR 7. September 2018 2 3 programm programm FR 7. September 2018 Kölner Philharmonie / 20.00 Uhr Johannes Brahms 19.00 Uhr Einführung Konzert Nr. 1 d-Moll Wibke Gerking für Klavier und Orchester op. 15 I. Maestoso II. Adagio III. Rondo. Allegro non troppo ~ 45 Minuten pause Arnold Schönberg Pelleas und Melisande Sinfonische Dichtung op. 5 (nach dem Drama von Maurice Maeterlinck) [I.] Die Achtel ein wenig bewegt – Heftig – Lebhaft – [II.] Sehr rasch – Ein wenig bewegt – [III.] Langsam – Ein wenig bewegter – [IV.] Sehr langsam – Etwas bewegt – In gehender Bewegung – Breit ~ 43 Minuten Jukka-Pekka Saraste Igor Levit Klavier WDR Sinfonieorchester Jukka-Pekka Saraste Leitung sendetermin wdr 3 SA 15. September 2018 20.04 Uhr wdr 3 konzertplayer digitales programmheft Zum Nachhören finden Sie Unter wdr-sinfonieorchester.de dieses Konzert 30 Tage lang im steht Ihnen fünf Tage vor WDR 3 Konzertplayer: wdr3.de jedem Konzert das jeweilige Programmheft zur Verfügung. Titelbild: Igor Levit 4 5 die werke die werke Die Ereignisse freilich überschlugen sich in den 1850er Jahren: 1853 veröffentlichte Schumann den Artikel »Neue Bahnen«, in dem er Brahms eine große Zukunft als Komponist prophezeite: »Am Cla- vier sitzend, fing er an wunderbare Regionen zu enthüllen. Wir wurden in immer zauberischere Kreise hineingezogen. Dazu kam ein ganz geniales Spiel, das aus dem Clavier ein Orchester von wehklagenden und lautjubelnden Stimmen machte. Es waren So- naten, mehr verschleierte Symphonien«. Damit war dem jungen KONZERT NR. 1 D-MOLL Komponisten klar, dass von ihm Sinfonisches erwartet wurde. Ent- sprechend wollte Brahms seine ursprünglich für zwei Klaviere kon- FÜR KLAVIER UND zipierte d-Moll-Sonate umarbeiten. -

Current Review

Current Review Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonic Works aud 21.450 EAN: 4022143214508 4022143214508 Gramophone (Philip Clark - 2015.03.17) Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light—when you’re Robert Schumann, angels are terrifying too. The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn—but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy. The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles—to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. -

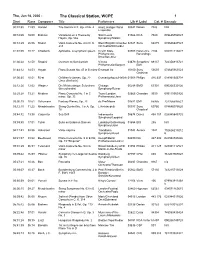

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Jun 18, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:59 Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind 00341 Denon 7026 N/A Ensemble 00:14:2918:00 Brahms Variations on a Theme by Saint Louis 01966 RCA 7920 078635792027 Haydn, Op. 56a Symphony/Slatkin 00:33:29 26:06 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 4 in D, K. Stern/English Chamber 02925 Sony 66475 074646647523 218 Orchestra/Schneider 01:01:0528:17 Chadwick Aphrodite, a symphonic poem Czech State 03308 Reference 2104 030911210427 Philharmonic, Recordings Brno/Serebrier 01:30:2212:50 Rossini Overture to Semiramide Vienna 03679 Seraphim/ 69137 724356913721 Philharmonic/Sargent EMI 01:44:1214:53 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 47 in B minor Emanuel Ax 10100 Sony 53635 074645363523 Classical 02:00:3510:51 Bizet Children's Games, Op. 22 Concertgebouw/Haitink 01008 Philips 416 437 028941643728 (Jeux d'enfants) 02:12:2612:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 02:25:2833:21 Medtner Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Tozer/London 02666 Chandos 9039 095115903926 minor, Op. 33 Philharmonic/Jarvi 03:00:1910:51 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 du Pre/Moore 09531 EMI 65955 724356595521 03:12:1031:22 Mendelssohn String Quintet No. 1 in A, Op. L'Archibudelli 05537 Sony 60766 074646076620 18 Classical 03:44:32 13:38 Carpenter Sea Drift Indianapolis 08678 Decca 458 157 028945845725 Symphony/Leppard 03:59:4017:01 Tubin Suite on Estonian Dances Lubotsky/Gothenburg 01654 BIS 286 N/A Symphony/Jarvi 04:17:41 02:56 Halvorsen Valse caprice Trondheim 01943 Aurora 1921 702626219212 Symphony/Ruud 6 04:21:3738:22 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. -

559700 Bk Hanson US

559642 bk Baker US_559642 bk Baker US 22/06/2012 21:07 Page 12 AMERICAN CLASSICS CLAUDE BAKER The Glass Bead Game Awaking the Winds • Shadows • The Mystic Trumpeter St. Louis Symphony Leonard Slatkin • Hans Vonk 8.559642 12 559642 bk Baker US_559642 bk Baker US 22/06/2012 21:07 Page 2 Claude Baker (b. 1948): The Glass Bead Game Hans Vonk Awaking the Winds • Shadows: Four-Dirge Nocturnes • The Mystic Trumpeter The distinguished Dutch conductor Hans Vonk assumed The Glass Bead Game (1982, rev. 1983) attained through a complete consumption and exhaustive the post of Music Director and Conductor of the St. Louis analysis only of the fruits of the past. Such a society, says Symphony in September 1996. A sought-after guest In 1943, the German novelist and philosopher Hermann Hesse, no matter how elite, how intellectual, how esoteric, conductor as well, he appeared with many of the world’s Hesse completed his last and (excepting Narcissus und must stagnate, wither and die. most prestigious orchestras and led performances at major Goldmund) greatest novel, Das Glasperlenspiel. Winner Claude Baker is saying much the same thing in his opera houses in Europe and North America, while also of the 1946 Nobel Prize for Literature, this book, the sum three-movement musical piece based on The Glass Bead remaining active in the musical life of his native Holland. and summit of Hesse’s thought and one of the most truly Game. His work, bearing the same title, is far more than a Vonk was Chief Conductor of the Netherlands Opera from relevant books of the era, was translated into English in programmatic reflection of Hesse’s novel; it is, remarkably, 1976 to 1985, during which time he was also Conductor of 1969 and brought out first with the title The Glass Bead like the novel, a philosophical mirror as well, in which the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic (1973-1979) and Game and subsequently as Magister Ludi (Master of the Baker utilizes Hesse’s methods and imagery to comment Associate Conductor of London’s Royal Philharmonic Game). -

Celebrating Slatkin Booklet FINAL

Marie-Hélène Bernard St. Louis Symphony Orchestra President & CEO Dear Leonard, When you made your conducting debut with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in 1968, who could have imagined that we’d gather on the same stage 50 years later to celebrate a remarkable partnership – one that redefined what an American orchestra could – and continues – to be. What you built with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra starting 50 years ago remains core to our mission. It’s the solid bedrock we’ve been building on for the past five decades: enriching lives through the power of music. Your years with the SLSO reshaped this orchestra, earning it the title of “America’s Orchestra.” You connected with our community – both here in St. Louis and on national and international stages. By taking this orchestra on the road, you introduced the SLSO and St. Louis to the world. You recorded with this orchestra more than any other SLSO music director, championing American composers and music of our time. Your passion for music education led to your founding of the St. Louis Symphony Youth Orchestra, which is the premiere experience for young musicians across our region. Next year, we will mark the Youth Orchestra’s golden anniversary and the thousands of lives it has impacted. We admire you for your remarkable spirit and talent and for your amazing vision and leadership. We are thrilled you have returned home to St. Louis and look forward to many years sharing special moments together. On behalf of the entire St. Louis Symphony Orchestra family, congratulations on the 50th anniversary of your SLSO debut. -

Double Anniversary for the Israeli-American Maestro of the Ruhr Region Steven Sloane's Projects and Concerts in the 2019/20 Season

Double anniversary for the Israeli-American maestro of the Ruhr region Steven Sloane's projects and concerts in the 2019/20 season General Music Director in Bochum for 25 years and the 100th birthday of his orchestra – 2019 is a very special year for Steven Sloane and his audience. The orchestra's anniversary year has been bookended at the start of the 19/20 season by a Ruhrtriennale production of a new music-theatre work by Kornél Mundruczó, and the regional capital of the Ruhr area also has some surprises in store in the symphonic realm. A second music-theatre highlight will follow in the spring with the first German performance of David Lang's “Prisoner of the State,” of which Sloane will give more national premières in Rotterdam, Bruges, Barcelona and Malmö. At the Swedish opera house, he will also be in charge of the new production of Puccini's “Tosca” from December as Principal Guest Conductor. In addition, as the Music Director Designate of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, Sloane will already be presenting three programmes with his new orchestra. These days, you'd need to search for a long time to find a General Music Director who has held this position in the same location for a quarter of a century while instigating the kind of thoroughgoing changes that Steven Sloane has in Bochum, displaying a constant innovative energy both artistically and in the field of cultural policy. Since he took up his position in the heart of the Ruhr area in 1994, he has turned the Bochumer Symphoniker (BoSy for short) into one of the top German orchestras. -

Naamloos 2.Pages

JOOST SMEETS CONDUCTOR JOOST SMEETS PAGINA: !1 Joost Smeets Lindepad 3 6017BW Thorn Nederland PHONE: +31 6 22387357 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.joostsmeets.com VIDEOS: https://vimeopro.com/culture2share/joost-smeets-conductor JOOST SMEETS PAGINA: !2 Biography 1st Prize winner of the Cordoba Conducting Competition Spain 2013, 1st Prize winner of the Black Sea International Conducting Competition Constanta Romania 2014, 1st Prize winner of the London Classical Soloïsts Conducting Competition United Kingdom 2016 2nd Prize winner of the Antal Dorati Int. Conducting Competition Budapest Hungary 2015, 3rd Prize winner (1st and 2nd Prize are not awarded) of the Ferruccio Busoni Int. Conducting Competition Empoli, Italy 2016 Principal Conductor and Artistic Director of the Chamber Philharmonic der Aa Groningen Holland (2010-2016) conducted with great acclaim in his career renowned orchestras in Opera and Symphonic programs including: - Boise Philharmonic Orchestra USA - Letvian National Symphony Orchestra Riga Letvia - North-Netherlands Symphony Orchestra Groningen Holland - Koszalin Philharmonic “Stanislaw Moniuszko” Poland - Wuhan Philharmonic Orchestra China - State Opera Rousse, Bulgaria - MAV Symphony Orchestra Budapest, Hungary - St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra Russia - Cordoba Symphony Orchestra Spain - Artez Conservatory Symphony Orchestra Zwolle Holland - Tomsk Philharmonic Orchestra Russia - Limburgs Symphony Orchestra Maastricht Holland - National Bulgarian Opera Bourgas Bulgaria - Württembergische Philharmonie